Frederick Mackenzie, born circa 1787 and passing in 1854, stands as a significant figure in the annals of British art, particularly revered for his exceptional skill as a watercolour painter and an architectural draughtsman. His meticulous and evocative renderings of Gothic ecclesiastical structures, as well as other significant edifices, have provided an invaluable record of Britain's architectural heritage. Mackenzie's career unfolded during a period of immense artistic ferment and a burgeoning appreciation for the nation's historical monuments, a context in which his talents found fertile ground.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Born in England around 1787, the precise details of Frederick Mackenzie's earliest years and initial artistic training are somewhat scarce, a commonality for many artists of his era not born into established artistic dynasties. However, it is evident that he displayed a prodigious talent from a young age. His formal entry into the London art scene was marked by his first exhibition at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in 1804. To exhibit at such a venerable institution at the approximate age of sixteen or seventeen was a notable achievement, signalling the arrival of a promising new talent.

It is understood that Mackenzie received some of his formative training under John Adey Repton, an architect and son of the more famous landscape architect Humphry Repton. This association was pivotal, likely honing Mackenzie's eye for architectural detail, perspective, and the accurate representation of complex structures. This tutelage would have provided him with the foundational skills necessary for his later specialisation. His collaboration with Repton extended to significant projects, including the creation of numerous drawings for the architectural features of Oxford University and its renowned public schools. These early works already demonstrated a keen observational capacity and a refined draughtsmanship.

Association with the Society of Painters in Water Colours

A crucial development in Mackenzie's career was his association with the Society of Painters in Water Colours, often referred to as the Old Watercolour Society (OWS). He became an associate member in 1812 and was elected a full member in 1813. This society, founded in 1804 by artists like William Frederick Wells, Samuel Shelley, and William Sawrey Gilpin, played an instrumental role in elevating the status of watercolour painting, which had often been considered secondary to oil painting. The OWS provided a dedicated venue for watercolourists to exhibit and sell their work, fostering a sense of community and professional identity.

Mackenzie was not merely a passive member; he became deeply involved in the society's administration. He served as its treasurer for an extended period, from 1831 until his death in 1854. This long tenure speaks to the trust and respect he commanded among his peers, artists such as Copley Fielding, Peter De Wint, and David Cox, who were also prominent members of the OWS. His commitment to the society underscored his dedication to the medium of watercolour and its practitioners.

The Architectural Draughtsman

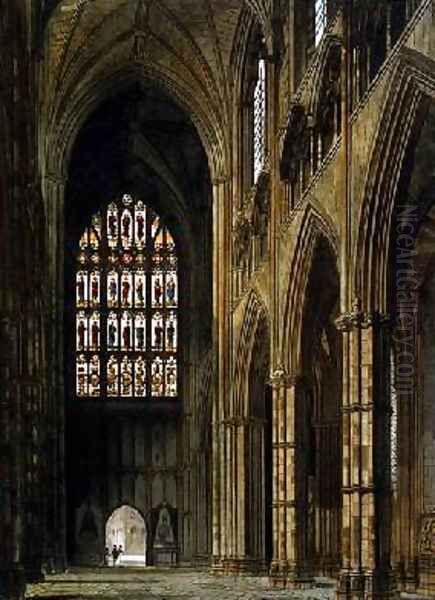

Frederick Mackenzie's enduring reputation rests primarily on his exquisite architectural drawings. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture not only the structural intricacies of buildings but also their atmospheric qualities and historical resonance. His preferred subjects were often Gothic cathedrals and churches, whose soaring vaults, intricate tracery, and venerable patinas offered rich material for his brush.

His work was characterized by an exceptional accuracy in perspective, a rich and nuanced palette, and an unwavering attention to detail. He did not merely record architectural forms; he imbued them with a sense of grandeur and historical weight. This was a period when antiquarianism and a romantic interest in the medieval past were gaining momentum, fueled by writers like Sir Walter Scott and architects like Augustus Pugin, who championed the Gothic Revival. Mackenzie's art resonated with this cultural climate, providing visual sustenance for a public increasingly fascinated by its national heritage.

Many of Mackenzie's drawings were commissioned for illustrated books, a booming industry in the 19th century. He collaborated extensively with the antiquary and publisher John Britton on several landmark publications. These included Britton's Architectural Antiquities of Great Britain (1807-1826) and Cathedral Antiquities of England (1814-1835). For these ambitious projects, Mackenzie produced a vast number of highly detailed watercolours of cathedrals such as Salisbury, Winchester, and York, which were then translated into engravings by skilled craftsmen like John Le Keux and his brother Henry Le Keux. These publications disseminated images of Britain's architectural treasures to a wider audience and remain invaluable historical documents.

Notable Works and Commissions

Beyond his contributions to Britton's publications, Mackenzie undertook several other significant commissions. His involvement with the Oxford Almanacks is noteworthy. These were annual single-sheet almanacs published by Oxford University Press, traditionally illustrated with views of the university's colleges and buildings. Mackenzie contributed drawings for these prestigious publications, further cementing his reputation for depicting academic architecture with elegance and precision.

One of his most historically significant series of works documented the Collegiate Chapel of St Stephen at Westminster, which had housed the House of Commons. After the devastating fire of 1834 that largely destroyed the old Palace of Westminster, Mackenzie was commissioned to record the surviving architectural features and ruins of St Stephen's Chapel. These drawings, later published as The Architectural Antiquities of the Collegiate Chapel of St Stephen, Westminster, The Late House of Commons (1844), are of immense historical importance, providing a detailed visual account of a building that was central to British political life for centuries. His meticulous renderings captured the charred remains and exposed structures with both accuracy and a poignant sense of loss.

Mackenzie also produced Illustrations of Windsor Castle (published by Henry Graves, 1840s, with text by John Britton and others), showcasing the grandeur of this royal residence. His ability to convey the scale and majesty of such iconic buildings was unparalleled. While the provided information mentions The Raising of Lazarus in the National Gallery and The Tomb of George Villiers, these are less typical of his known oeuvre, which overwhelmingly focuses on architectural subjects. It is possible that The Tomb of George Villiers refers to a drawing of the monument within a larger architectural setting, such as Westminster Abbey, which would be consistent with his specialisation. The attribution of a biblical scene like The Raising of Lazarus to Mackenzie, the architectural specialist, warrants careful consideration, as it might be a confusion with another artist. His primary fame and the bulk of his identifiable work lie firmly in architectural representation.

Artistic Style and Technique

Mackenzie's artistic style evolved over his long career, but certain characteristics remained constant. His early work, while accomplished, perhaps showed more of the prevailing Romantic sensibility, with a focus on picturesque effects. As he matured, his style became even more rigorous and precise, though without sacrificing the atmospheric depth that made his watercolours so compelling.

He was a master of perspective, able to render complex interior views of cathedrals with their receding aisles and soaring vaults with convincing spatial depth. His use of colour was sophisticated; he could capture the subtle hues of ancient stonework, the play of light through stained glass, and the varying textures of wood, metal, and fabric. His detailing was extraordinary, from the delicate carving of a capital to the intricate patterns of a tiled floor. Yet, this meticulousness rarely led to a dry or merely topographical representation. Instead, his works often convey a sense of reverence for the structures he depicted, hinting at their historical narratives and spiritual significance.

Compared to some of his contemporaries, like the visionary J.M.W. Turner or the pastoral John Constable, Mackenzie's focus was narrower but no less profound within its chosen sphere. While Turner might use architecture as a component in a dramatic, light-filled landscape, and Constable focused on the English countryside, Mackenzie dedicated himself to the faithful yet artistic portrayal of man-made structures, particularly those of historical and national importance. His work shares affinities with other architectural specialists of the era, such as Samuel Prout, known for his picturesque views of European architecture, though Mackenzie's focus was predominantly British.

The Context of Antiquarianism and Topographical Art

To fully appreciate Frederick Mackenzie's contribution, it is essential to understand the cultural and artistic context in which he worked. The late 18th and early 19th centuries witnessed a surge in antiquarian interest – a fascination with the material remains of the past. This was coupled with the rise of topographical art, which aimed to provide accurate visual records of specific places, landscapes, and buildings.

Watercolour was the ideal medium for this type of work. It was portable, allowing artists to sketch on site, and it could achieve a high degree of detail and subtle colouration. The demand for topographical views was fueled by several factors: the growth of domestic tourism (as continental travel became difficult during the Napoleonic Wars), a burgeoning national pride, and the aforementioned antiquarian curiosity. Illustrated books, travelogues, and collections of prints became immensely popular.

Artists like Thomas Girtin, who died young but had a profound impact, and J.M.W. Turner, had already demonstrated the expressive potential of watercolour. Mackenzie built upon this foundation, applying the medium with consummate skill to the specific demands of architectural representation. His work served not only an aesthetic purpose but also a documentary one, preserving the appearance of buildings that might since have been altered or, in some cases, lost. He can be seen as part of a lineage of artists who meticulously recorded the built environment, a tradition that included earlier figures like Wenceslaus Hollar in the 17th century.

Mackenzie and His Contemporaries

Mackenzie's career spanned a dynamic period in British art. He was a contemporary of the great Romantic landscape painters Turner and Constable, as well as a host of talented watercolourists. Within the Society of Painters in Water Colours, he would have interacted with artists like John Varley, a highly influential teacher and landscape painter, and George Fennel Robson, known for his mountain landscapes.

While his primary collaborations were with publishers and antiquaries like John Britton, his work existed within a broader artistic ecosystem. The architects of the day, such as Sir John Soane, known for his neoclassical designs, and later, the proponents of the Gothic Revival like Augustus Pugin and Sir Charles Barry (who, with Pugin, designed the new Palace of Westminster after the 1834 fire), were shaping the architectural landscape that artists like Mackenzie recorded. Although Mackenzie predominantly depicted existing historical structures, his work contributed to the visual vocabulary that informed the Gothic Revival.

His dedication to architectural accuracy set him somewhat apart from artists who might use buildings more freely as elements in picturesque compositions, such as Thomas Hearne or Edward Dayes in the preceding generation. Mackenzie's commitment was to the integrity of the structure itself, presented with artistic skill but with an underlying fidelity to its form and detail.

Later Career and Legacy

Frederick Mackenzie remained active and respected throughout his career. His long service as treasurer of the Old Watercolour Society from 1831 to 1854 indicates his standing within the artistic community. He continued to produce high-quality architectural watercolours, contributing to the visual record of Britain's heritage until his death in 1854.

His legacy is multifaceted. Firstly, his works are invaluable historical documents. They provide detailed and accurate representations of numerous significant buildings, some of which have since undergone alteration or decay. His drawings of St Stephen's Chapel, for instance, are a prime example of art serving a crucial archival function.

Secondly, he contributed to the elevation of watercolour as a serious artistic medium. Through his skilled practice and his involvement with the OWS, he helped to secure its place in the hierarchy of British art. His technical mastery demonstrated the capabilities of watercolour for detailed and nuanced representation.

Thirdly, his art played a role in fostering public appreciation for Britain's architectural past, particularly its Gothic heritage. In an era of industrialization and rapid change, his images offered a connection to a seemingly more stable and spiritually resonant past. His work, disseminated through engravings and publications, helped to shape the popular image of Britain's cathedrals and ancient monuments.

Today, Frederick Mackenzie's watercolours are held in numerous public collections, including the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and various university and regional galleries. They continue to be admired for their technical brilliance, their historical accuracy, and their evocative power. He remains a key figure for anyone studying British architectural history or the development of watercolour painting in the 19th century. His dedication to his craft and his chosen subject matter ensured that future generations would have access to a rich visual archive of Britain's architectural glories, as seen through the eyes of a supremely gifted artist.