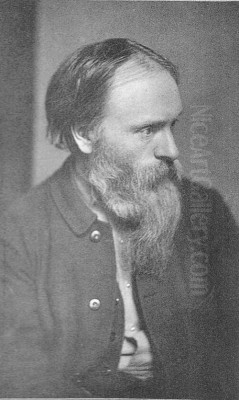

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones stands as one of the most significant and distinctive figures in late nineteenth-century British art. A painter and designer of remarkable talent and vision, he navigated the currents of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and became a leading light of the Aesthetic Movement. His work, characterized by its dreamlike quality, romantic sensibility, and deep engagement with myth, legend, and literature, created a unique artistic realm that offered an escape from the industrial realities of Victorian England. His influence extended beyond painting into the decorative arts, shaping tastes and inspiring artists well into the twentieth century.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Edward Coley Burne Jones (he added the hyphen later in life) was born in Birmingham on August 28, 1833. His early life was marked by tragedy; his mother, Elizabeth Coley Jones, died just six days after his birth. He was raised by his grieving father, Edward Richard Jones, a frame-maker and gilder of Welsh descent, and a devoted, though somewhat austere, housekeeper. This early loss perhaps contributed to the melancholic and ethereal quality found in much of his later work.

His upbringing in the industrial heartland of Birmingham exposed him to the stark contrasts of Victorian society. Though his father's business was modest, the young Burne-Jones received a good education, initially attending King Edward VI School in Birmingham. He showed early artistic promise but was destined, according to his father's wishes and his own initial inclination, for a career in the Church.

In 1853, Burne-Jones went up to Exeter College, Oxford, to study theology. This move proved pivotal, not for his religious vocation, but for his artistic destiny. At Oxford, he formed a profound and lifelong friendship with William Morris, another student wrestling with his future path. They discovered a shared passion for the medieval world, for literature (especially Chaucer and Malory), and for art. They were particularly captivated by the ideals of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, whose work they encountered through illustrations and critical writings, notably those of John Ruskin.

Inspired by the art they admired, particularly the work of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris made the momentous decision to abandon their clerical ambitions and dedicate their lives to art. Burne-Jones, largely self-taught initially, sought out Rossetti in London in 1856. Rossetti, a leading figure of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood alongside William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, took the younger artist under his wing, offering guidance and encouragement. This mentorship was crucial in shaping Burne-Jones's early artistic direction.

The Pre-Raphaelite Connection and Morris & Co.

Burne-Jones quickly became associated with the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism, a phase that moved beyond the intense naturalism of the early Brotherhood towards more decorative, symbolic, and medievalizing themes. His early works clearly show the influence of Rossetti, with their rich colours, detailed patterns, and focus on romantic and literary subjects. He absorbed the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on craftsmanship, emotional intensity, and a rejection of the perceived triviality of academic art.

The collaboration between Burne-Jones and William Morris became one of the most fruitful partnerships in the history of British art and design. In 1861, together with Rossetti, Ford Madox Brown, Philip Webb, Peter Paul Marshall, and Charles Faulkner, they founded the decorative arts firm Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (later reorganized as Morris & Co. in 1875). This venture aimed to counteract the perceived decline in design standards brought about by industrial mass production, advocating for handcrafted quality and artistic integrity in everyday objects.

Burne-Jones became the firm's chief designer, contributing prolifically across various media. His designs for stained glass were particularly significant, adorning churches and buildings throughout Britain and beyond. Notable examples include windows for Salisbury Cathedral, Christ Church Cathedral in Oxford, and St. Philip's Cathedral in Birmingham. His elongated, graceful figures and rich, jewel-like colours translated beautifully into glass, revitalizing the medium.

Beyond stained glass, Burne-Jones designed intricate tapestries, ceramic tiles, mosaics, furniture decorations, and illustrations for the firm. His tapestry designs, often woven at Morris's Merton Abbey workshops, included monumental works like the Holy Grail series, based on Arthurian legend, which exemplify the firm's ambition to create integrated, immersive artistic environments. His collaboration with Morris extended to book illustration, culminating in the magnificent Kelmscott Press edition of The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer (1896), for which Burne-Jones provided 87 woodcut illustrations, a crowning achievement of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Development of a Unique Artistic Vision

While initially influenced by Rossetti, Burne-Jones's style evolved significantly during the 1860s. He moved away from the intense, sometimes claustrophobic, compositions of his mentor towards a more serene, ethereal, and classical aesthetic. His figures became more elongated and graceful, often imbued with a sense of languor or melancholy. His colour palettes shifted towards cooler tones, blues, greens, and muted golds, enhancing the dreamlike atmosphere of his paintings.

He drew inspiration from a wide range of sources. While deeply versed in medieval literature and legend, he also looked intently at Italian Renaissance art. He made several trips to Italy, studying the works of masters like Sandro Botticelli, Andrea Mantegna, and Michelangelo. The linear grace of Botticelli and the sculptural forms of Michelangelo left a discernible mark on his figure drawing and composition. However, unlike many Victorian classicists, Burne-Jones filtered these influences through his own romantic sensibility, prioritizing mood and symbolic resonance over archaeological accuracy.

His subjects were drawn predominantly from mythology (Greek and Roman), Arthurian legend, biblical stories, and allegorical themes. He created narrative cycles, such as the Perseus series and the Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty) series, allowing him to explore stories in depth across multiple canvases. These works transport the viewer to otherworldly realms, populated by knights, princesses, angels, and mythical beings, far removed from the concerns of contemporary life. This escapism was central to his appeal, offering a vision of beauty and enchantment in an age of rapid change and industrialization.

Major Works and Signature Style

Burne-Jones's mature style is exemplified by several key masterpieces. The Beguiling of Merlin (1872-77) depicts the Arthurian sorceress Nimue entrapping Merlin in a hawthorn bush. The painting showcases his characteristic elongated figures, the intricate rendering of foliage and drapery, and the palpable sense of enchantment and weary resignation. It became an iconic image of the Aesthetic Movement.

King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid (1884) illustrates a legend about an African king who falls in love with a humble beggar girl. The composition emphasizes the contrast between the king's opulent armour and the maid's simple tunic, yet unites them through the intensity of Cophetua's gaze and the maid's serene, almost detached, beauty. The meticulous detail, rich textures, and the overall atmosphere of quiet reverence made it one of his most acclaimed works, earning him accolades at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle.

The allegorical painting Love and Life (c. 1883-84) shows Love guiding the hesitant figure of Life up a rocky path. It embodies his more symbolic and less narrative approach, focusing on universal themes and emotional states. The delicate rendering of the figures and the soft, luminous landscape contribute to its gentle, hopeful mood.

Other significant works include the haunting The Depths of the Sea (1886), the ambitious The Star of Bethlehem (1887-91, a large watercolour commissioned for Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery), and the later, monumental The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon (1881–1898), an epic canvas left unfinished at his death, representing his lifelong fascination with Arthurian legend. His technique often involved meticulous drawing as a foundation, followed by layers of oil paint or watercolour and gouache, sometimes incorporating gold paint to enhance the luminosity and decorative quality, reflecting his design sensibilities.

The Aesthetic Movement and Wider Recognition

By the 1870s, Burne-Jones had become a central figure in the Aesthetic Movement. This movement, which included artists like James McNeill Whistler, Albert Moore, and Frederic Leighton, championed the idea of 'art for art's sake'. It prioritized beauty, harmony, and sensory experience over narrative clarity or overt moralizing. Burne-Jones's emphasis on mood, decorative pattern, refined forms, and evocative, often ambiguous, subjects aligned perfectly with Aesthetic ideals.

His withdrawal from the Royal Watercolour Society in 1870, due to controversy over the nudity in his Phyllis and Demophoön, marked a turning point. He retreated from public exhibition for several years, focusing intensely on his work. His triumphant return came with the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877, a venue sympathetic to Aestheticism. His exhibited works, including The Beguiling of Merlin and The Days of Creation, caused a sensation, cementing his reputation as a leading artist of the day.

His fame grew both nationally and internationally. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1885 (though he exhibited there only once and resigned in 1893, feeling out of sympathy with the institution). His influence spread to France and Belgium, where he was admired by Symbolist artists like Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, who responded to the suggestive, dreamlike qualities of his art. He received numerous honours, including honorary degrees from Oxford and Cambridge, and was awarded the Legion of Honour in France after the success of King Cophetua in Paris. In 1894, he accepted a baronetcy, becoming Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, 1st Baronet, of Rottingdean.

Versatility and Design Philosophy

Burne-Jones's career demonstrates an extraordinary versatility. He moved seamlessly between the so-called 'fine' arts of painting and drawing and the 'applied' arts of design. This refusal to accept a rigid hierarchy between disciplines was central to the philosophy he shared with William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement. They believed that art should permeate all aspects of life, and that functional objects should be beautiful.

His designs for stained glass, tapestry, and illustration were not mere sidelines but integral parts of his artistic output, often exploring the same themes and figures found in his paintings. His deep understanding of different materials and techniques allowed him to adapt his style effectively. For instance, his stained-glass designs utilized strong outlines and flat areas of colour suited to the medium, while his tapestry designs employed complex patterns and rich textures. His illustrations for the Kelmscott Press showed a mastery of line and composition within the constraints of the printed page. This holistic approach to art-making was a key aspect of his legacy.

He also occasionally ventured into other areas, including designs for jewellery, metalwork, and even theatrical costumes. His interaction with other artists extended internationally, as seen in his contact with the German painter Melchior Lechter, highlighting his reach beyond Britain.

Personal Life and Character

Despite his fame, Burne-Jones was often described as shy, sensitive, and prone to bouts of melancholy. He married Georgiana MacDonald, one of five remarkable sisters connected to the arts, in 1860. Their marriage endured despite Burne-Jones's intense, and sometimes tumultuous, relationship with Maria Zambaco, a Greek heiress and artist's model, in the late 1860s. This affair caused considerable personal turmoil but also arguably fueled the emotional intensity of some works from that period.

He maintained a close circle of friends, including Morris, Rossetti, the writer George Eliot, and later, the young Rudyard Kipling (his nephew by marriage). His studio became a sanctuary where he could immerse himself in the imaginative worlds he depicted. Anecdotes suggest a gentle, humorous side, often expressed through whimsical caricatures and drawings made for family and friends. His relationship with patrons and models, like the aforementioned Katie Lewis, whose portrait he painted, sometimes blurred the lines between the professional and the personal, reflecting the complex social dynamics of the Victorian art world.

His art can be seen as a form of personal refuge, a deliberate turning away from the perceived ugliness and materialism of the modern industrial world towards an idealized realm of beauty, romance, and spiritual significance. This critique of contemporary society, shared with Morris and Ruskin, underpinned his artistic choices and resonated with audiences seeking an alternative vision.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones died suddenly from heart failure on June 17, 1898, at his home in Rottingdean, near Brighton. His death was widely mourned, and a memorial service was held at Westminster Abbey, a rare honour for an artist.

His influence was profound and far-reaching. As a cornerstone of the later Pre-Raphaelite movement and a leader of Aestheticism, he shaped the course of British art in the late nineteenth century. His emphasis on line, pattern, and symbolic meaning directly influenced the development of Art Nouveau across Europe. His dreamlike imagery and exploration of the subconscious resonated with the Symbolist movement.

Even artists of the early twentieth century acknowledged his impact. While modernism represented a radical break from Victorian aesthetics, figures like the young Pablo Picasso were known to have studied and admired Burne-Jones's work during their formative years, particularly his mastery of line and composition. His dedication to craftsmanship and the integration of art and design, championed through his work with Morris & Co., provided a powerful model for the Arts and Crafts movement and subsequent design philosophies.

Today, Burne-Jones is recognized as a unique and compelling figure in art history. His paintings and designs continue to captivate viewers with their intricate beauty, imaginative power, and melancholic charm. He created a distinct artistic language, drawing on the past to forge a vision that was both deeply personal and profoundly influential, securing his place as a master of romantic and symbolic art. His works remain treasured holdings in major museums worldwide, testaments to a singular artistic journey through myth, legend, and the enduring pursuit of beauty.