Umberto Brunelleschi stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early 20th-century European art, particularly celebrated for his contributions to illustration, fashion, and theatre design. An Italian artist who found his true calling in the vibrant artistic milieu of Paris, Brunelleschi carved a unique niche for himself with a style characterized by elegance, decorative richness, and a playful engagement with historical and exotic themes. His work, primarily associated with the Art Deco movement, graced the pages of luxurious magazines, brought classic literature to life, and added visual splendour to the stages of renowned theatres. Though sometimes confused with his namesake, the Renaissance architectural giant Filippo Brunelleschi, Umberto's legacy lies firmly in the graphic and decorative arts of a later, equally transformative era.

From Italy to the Parisian Art Scene

Umberto Brunelleschi was born in Montemurlo, near Pistoia in Tuscany, Italy, in 1879. His early years were spent in his native country, where he likely received initial artistic training, absorbing the rich cultural heritage of Italy. However, like many aspiring artists of his generation, he was drawn to the magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world at the turn of the century. He relocated there around 1900, immersing himself in the city's dynamic atmosphere.

Paris offered a fertile ground for Brunelleschi's talents. The Belle Époque was transitioning into a new century, brimming with artistic experimentation and a burgeoning market for graphic arts. Newspapers, satirical journals, and soon, lavish fashion magazines, provided ample opportunities for illustrators. Brunelleschi quickly began to make his mark, initially contributing work, including satirical cartoons, to publications like Le Rire. This early work allowed him to hone his skills and establish connections within the Parisian publishing world.

His Italian roots perhaps gave him a unique perspective, blending a Mediterranean sensibility with the chic modernism of Paris. This fusion would become a hallmark of his developing style. The move to Paris was pivotal, placing him at the epicentre of artistic innovation and providing the platform from which he would launch a diverse and successful career spanning several decades.

The Illustrator: Breathing Life into Books

One of Brunelleschi's most enduring contributions was his work as a book illustrator. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the essence of a text and translate it into visually captivating images. His illustrations were not mere accompaniments but interpretations that enhanced the reader's experience, often adding layers of charm, wit, or opulence to the narrative. He worked across a range of genres, illustrating classic literature, fairy tales, and historical memoirs.

His portfolio includes illustrations for renowned authors such as Voltaire, notably for Candide, where his elegant line and sense of irony found fertile ground. He also illustrated works by Alfred de Musset and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, demonstrating his versatility in adapting his style to different literary moods. Other notable projects included illustrations for Boccaccio's Decameron, bringing its medieval tales to life with Renaissance-inspired flair, and the adventurous Memoirs of Casanova, where he revelled in depicting 18th-century Venetian society.

Brunelleschi also lent his talents to fairy tales and children's literature, illustrating works by Hans Christian Andersen and Charles Perrault. In these, his capacity for fantasy and enchantment shone through, creating magical worlds filled with graceful figures and decorative detail. His style, often characterized by clear outlines, flat areas of colour, and meticulous attention to costume and setting, was perfectly suited to the printed page.

The Pseudonym: Aron-al-Rashid

Intriguingly, Brunelleschi sometimes worked under the pseudonym "Aron-al-Rashid" (or Harun al-Rashid). This choice, referencing the famous Caliph from the Arabian Nights, points directly to the Orientalist fascination prevalent in European art and design during the early 20th century. This trend was significantly fueled by the sensational success of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, whose productions, with exotic sets and costumes often designed by Léon Bakst, captivated Parisian audiences from 1909 onwards.

Using this pseudonym, Brunelleschi created works that explicitly played with themes of the exotic East – harem scenes, opulent palaces, and characters drawn from Middle Eastern folklore. These illustrations often featured rich patterns, vibrant jewel tones, and a sense of luxurious fantasy. The name itself added a layer of mystique and theatricality, aligning the artist with the romanticized visions of the Orient that were highly fashionable at the time.

While not all his work bore this name, the adoption of the pseudonym underscores a key element of his artistic identity: a willingness to embrace fantasy, theatricality, and the allure of the exotic. It highlights his engagement with contemporary trends and his skill in crafting a specific persona or mood through his art, whether under his own name or an assumed one.

Fashion Plates and the Gazette du Bon Ton

Brunelleschi's involvement with fashion illustration placed him at the forefront of documenting and shaping early 20th-century style. He became a key contributor to several influential French fashion journals, most notably the Gazette du Bon Ton. Launched in 1912, this publication was a benchmark of luxury and artistic quality, showcasing the latest creations by top Parisian couturiers like Paul Poiret, Jeanne Lanvin, and Charles Worth.

The Gazette employed a group of talented artists, often referred to as the "Knights of the Bracelet," who elevated fashion illustration to an art form. Alongside contemporaries such as George Barbier, Georges Lepape, André Édouard Marty, Charles Martin, and Bernard Boutet de Monvel, Brunelleschi created exquisite plates that were far more than simple representations of clothing. They depicted elegant figures in stylish settings, evoking a mood of sophistication, leisure, and modernity.

His fashion illustrations captured the fluid lines of Art Nouveau transitioning into the more structured elegance of early Art Deco. He depicted women embodying the era's ideals of grace and chic, often set against decorative backgrounds that complemented the attire. His work appeared not only in the Gazette but also in other prominent magazines like Journal des Dames et des Modes and Femina, solidifying his reputation as a leading fashion illustrator.

The Pochoir Technique

A significant factor in the visual impact of Brunelleschi's illustrations, particularly those for luxury publications like the Gazette du Bon Ton, was the use of the pochoir technique. This was a sophisticated method of stencil-based printing, meticulously executed by hand, which allowed for the application of rich, vibrant, and opaque layers of watercolour or gouache. Unlike standard colour printing methods of the time, pochoir produced exceptionally bright and saturated colours with flat, clearly defined shapes.

This technique perfectly suited Brunelleschi's style, which relied on strong outlines, decorative patterns, and bold colour contrasts. The pochoir process enhanced the jewel-like quality of his palette and the crispness of his designs. Each print was essentially a hand-coloured artwork, contributing to the exclusivity and high cost of the publications they graced. The technique required considerable skill from the artisans (coloristes) who applied the colours through a series of precisely cut stencils, often numbering twenty or thirty for a single image.

Brunelleschi, along with artists like Barbier, Erté (Romain de Tirtoff), and Lepape, mastered the possibilities of pochoir. It became synonymous with the high style of Art Deco graphics, lending an air of artisanal luxury and visual intensity that defined the era's finest illustrated works. His proficiency with this technique was integral to the distinctive look and feel of his contributions to both book and magazine illustration.

Designing for the Stage: La Scala and the Folies Bergère

Beyond the printed page, Brunelleschi extended his artistic vision to the theatre, designing spectacular sets and costumes. His flair for the dramatic, his love of historical and exotic themes, and his mastery of colour and decoration made him a natural fit for the stage. He received prestigious commissions, working for major venues in both Milan and Paris, demonstrating his international reputation.

He created designs for the renowned La Scala opera house in Milan. Designing for such a grand institution required an understanding of scale, historical accuracy (when needed), and the ability to create visually stunning environments that complemented the music and drama. His work likely included designs for operas that allowed for imaginative and opulent interpretations, possibly including works by Puccini, such as Turandot, which premiered posthumously but whose exotic setting aligns with Brunelleschi's interests.

In Paris, Brunelleschi brought his talents to a different kind of spectacle: the Folies Bergère. This famous music hall was known for its lavish revues, which featured elaborate costumes, dazzling sets, and a parade of performers. Brunelleschi's designs for the Folies Bergère would have emphasized fantasy, glamour, and theatricality, contributing to the venue's reputation for visual extravagance. His ability to blend elegance with playful sensuality was well-suited to the spirit of the Parisian revue. Other designers like Erté also famously worked for the Folies Bergère, placing Brunelleschi within a circle of artists defining the visual style of popular entertainment.

Artistic Style: Elegance, Fantasy, and Decoration

Umberto Brunelleschi's artistic style is a distinctive blend of influences, synthesized into a coherent and recognizable aesthetic. Primarily rooted in Art Deco, it incorporates elements of Art Nouveau linearity, Orientalism, Commedia dell'arte theatricality, and nostalgic references to 18th-century European elegance, particularly Venetian and French Rococo styles.

His figures are typically slender, graceful, and poised, rendered with a clear, confident line reminiscent perhaps of earlier artists like Aubrey Beardsley, but infused with a softer, more decorative sensibility. There is often a sense of movement and fluidity, even in static poses. Costumes are meticulously detailed, showcasing not only contemporary fashion but also historical attire or fantastical garments drawn from his imagination.

Colour is central to his work. He employed a rich, often jewel-like palette, using bold contrasts and harmonious combinations to create visually arresting compositions. The pochoir technique amplified this effect, resulting in vibrant, flat areas of colour that contribute to the decorative quality of his images. Pattern is another key element, seen in textiles, backgrounds, and architectural details, adding texture and richness.

A sense of fantasy and narrative pervades much of his work. Whether depicting a scene from a fairy tale, a historical anecdote, or a contemporary social gathering, Brunelleschi imbues his illustrations with a story-telling quality. There is often an element of whimsy, charm, or gentle irony. His Orientalist pieces transport the viewer to imagined lands of luxury, while his Commedia dell'arte figures capture the stylized gestures and masks of the Italian theatrical tradition. His frequent depictions of 18th-century fêtes galantes evoke a nostalgic longing for a bygone era of aristocratic leisure and refinement.

Representative Works and Themes

Identifying specific "masterpieces" for an illustrator and designer can be different from citing major paintings or sculptures. Brunelleschi's impact is cumulative, seen across his body of work in various media. However, certain projects and recurring themes stand out.

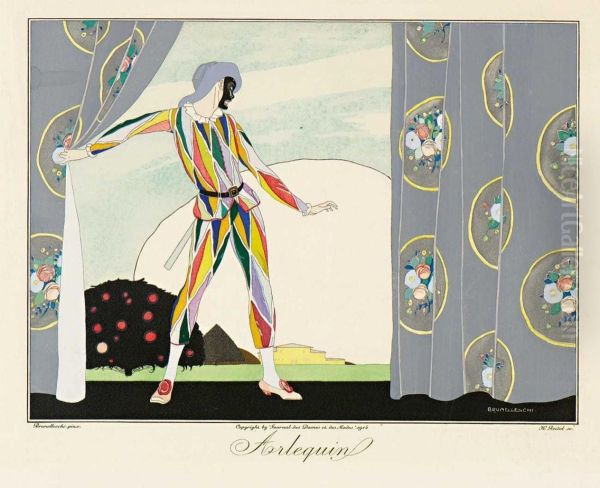

His portfolio Les Masques et les Personnages de la Comédie Italienne (1914), created with fellow artist George Barbier contributing text, is a significant work capturing his fascination with the Commedia dell'arte. The plates showcase iconic characters like Harlequin, Columbine, and Pierrot in dynamic poses and vibrant costumes, demonstrating his skill in capturing theatrical energy.

His illustrations for luxury editions of books like Voltaire's Candide, Abbé Prévost's Manon Lescaut, or Casanova's Memoirs are highly regarded examples of his narrative and decorative talents. Each series demonstrates his ability to adapt his style while maintaining his signature elegance and attention to detail. The plates for Andersen's fairy tales remain popular for their enchanting quality.

His contributions to the Gazette du Bon Ton represent the pinnacle of Art Deco fashion illustration. Any number of his plates from this journal could be considered representative, showcasing elegant women in haute couture designs by Poiret or Lanvin, often depicted in idealized settings that epitomize the era's aspirations towards sophistication and modern luxury.

Recurring themes include: the elegance of modern Parisian life, the fantasy of the Orient, the theatricality of the Commedia dell'arte, nostalgic visions of the 18th century (especially Venetian carnivals and French court life), and the enchantment of fairy tales. These themes allowed him to explore different facets of his decorative style, unified by his distinctive linear grace and vibrant colour sense.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Umberto Brunelleschi operated within a rich and interconnected artistic community in Paris, particularly during the vibrant decades preceding and following World War I. His work intersected with various movements and circles, primarily those related to illustration, fashion, theatre, and the broader Art Deco style.

His closest contemporaries were arguably the fellow illustrators of the Gazette du Bon Ton: George Barbier, Georges Lepape, André Édouard Marty, Charles Martin, and Bernard Boutet de Monvel. This group shared a common platform and often employed the pochoir technique, collectively defining the high style of fashion illustration in the 1910s and early 1920s. While their styles had individual nuances, they shared a commitment to elegance, decoration, and modernity.

In the realm of theatre and exoticism, Léon Bakst was a towering figure whose designs for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes profoundly influenced many artists, including Brunelleschi. The impact of Bakst's bold colours, dynamic patterns, and sensual exoticism can be seen echoed in Brunelleschi's Orientalist works and potentially his stage designs. Erté (Romain de Tirtoff), another Russian émigré, was a contemporary known for his highly stylized Art Deco designs for fashion (notably Harper's Bazaar covers) and theatre, including the Folies Bergère, sharing some common ground with Brunelleschi's theatrical work.

Within the broader Art Deco movement, Brunelleschi's work relates to painters and designers who emphasized stylized forms, luxurious materials, and decorative richness, such as Jean Dupas, known for his elegant murals and posters, or even the painter Tamara de Lempicka, whose portraits captured the glamorous, streamlined aesthetic of the era. While primarily an illustrator and designer, Brunelleschi's aesthetic resonated with the wider visual culture of Art Deco.

He also engaged with the legacy of earlier movements. The sinuous lines of Art Nouveau, exemplified by artists like Aubrey Beardsley, can be seen as an antecedent to his own refined linearity. His historical references connected him to a tradition of artists looking to the past, particularly the 18th century, for inspiration, a trend also visible in the work of some contemporaries. His interactions, collaborations, and competitions within this milieu shaped his career and contributed to the visual richness of the era.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Umberto Brunelleschi remained active as an artist through the interwar years and into the 1940s. While the peak of demand for lavish pochoir illustrations may have waned somewhat after the 1920s with changes in printing technology and aesthetic tastes, he continued to work as an illustrator and designer. The elegance and charm of his style retained their appeal, even as artistic trends evolved around him.

He continued to live and work in his adopted city of Paris, a testament to the enduring inspiration he found there. The city had provided the backdrop and the opportunities for his multifaceted career, from his early satirical drawings to his mature work in high fashion and theatre. He passed away in Paris in 1949, leaving behind a substantial body of work that captures the spirit of his time.

Umberto Brunelleschi's legacy lies in his significant contribution to the graphic arts and design of the Art Deco era. He was a master illustrator who brought literature to life with visual flair, a key figure in defining the sophisticated look of early 20th-century fashion journals, and a talented designer who added sparkle to the stage. His distinctive style, blending elegance, fantasy, historical nostalgia, and decorative richness, secured his place as an important artist of his generation. His work continues to be admired for its technical skill, aesthetic charm, and its evocative portrayal of a glamorous and visually exciting period in European cultural history.

Conclusion: An Artist of Elegance and Imagination

Umberto Brunelleschi navigated the artistic currents of the early 20th century with remarkable skill and adaptability. From his Italian origins to his flourishing career in Paris, he developed a unique and captivating visual language. As an illustrator, he imbued books and magazines with elegance and narrative charm, mastering the vibrant pochoir technique to create images of lasting beauty. His contributions to fashion illustration helped define the visual identity of haute couture in a golden age of graphic art. Furthermore, his work for the theatre demonstrated his ability to translate his decorative talents onto a larger scale, creating enchanting worlds on stage. Bridging the gap between fine art, commercial illustration, and decorative design, Brunelleschi remains a celebrated figure whose work continues to enchant viewers with its sophistication, fantasy, and masterful execution. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of illustration and design to capture and shape the aesthetic spirit of an era.