A Multifaceted Life: Law, Politics, and Art

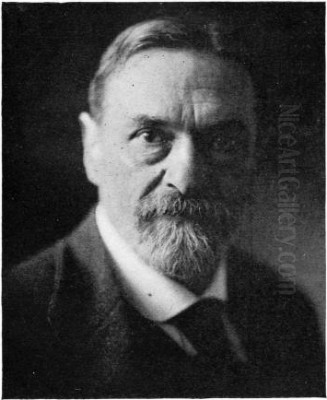

Pedro Figari stands as a towering figure in Uruguayan culture, a man whose life encompassed law, politics, writing, education, and, most enduringly, painting. Born in Montevideo in 1861 to Italian immigrant parents, Figari received a comprehensive education culminating in a law degree in 1886. His intellect and dedication quickly established him as a prominent figure in the legal and political spheres of Uruguay long before he gained fame as an artist.

Figari's early career was marked by a strong sense of justice and a commitment to public service. He served as a defense lawyer, gaining significant renown in the 1890s for his successful defense of an individual accused in a politically charged murder case, known historically as the "Calle Chaná murder case." His rigorous logic and persuasive arguments not only secured his client's acquittal but also established the case as a landmark in Uruguayan judicial history, showcasing his formidable analytical skills.

Beyond the courtroom, Figari was deeply engaged in the intellectual and political life of his nation. He was a writer, contributing essays and philosophical reflections, and actively participated in politics. His multifaceted activities demonstrated a profound engagement with the social and cultural fabric of Uruguay, laying the groundwork for the themes he would later explore so vividly in his art. His diverse experiences provided him with a unique perspective on Uruguayan society, its history, and its people.

Figari also dedicated himself to education, recognizing its power to shape society. His involvement in educational reform would become a significant part of his legacy, running parallel to his later artistic endeavors. This commitment to nurturing talent and fostering cultural understanding further highlights the breadth of his vision and his dedication to the development of his country. His life before art was already one of significant achievement and public contribution.

The Late Blooming of an Artist

Despite an early interest in art, including formal training in Italy under the painter Godofredo Sommavia and studies in Venetian galleries before even completing his law degree, Figari did not dedicate himself fully to painting until relatively late in life. It was around the age of 60, in the early 1920s, that he embarked seriously on the artistic career that would redefine his legacy and place him among the most important Latin American artists of the 20th century.

This transition marked a significant shift in focus. Having achieved prominence in law and politics, Figari turned his energies towards capturing the essence of his homeland through visual art. He moved to Buenos Aires in 1921, spending four formative years there, immersing himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of the Argentine capital. This period proved crucial for the development of his distinctive style and thematic concerns.

His first major solo exhibition took place at the Müller Gallery in Buenos Aires in 1921, garnering significant media attention and signaling the arrival of a unique artistic voice. This initial success encouraged him to pursue his artistic path with greater intensity. The Buenos Aires years were a period of intense creativity and interaction with the local art scene, further shaping his artistic identity.

In 1925, seeking broader horizons and deeper engagement with international modernism, Figari moved to Paris. He remained there until 1933, a period during which his reputation grew significantly on the international stage. Paris, then the undisputed center of the art world, provided him with exposure to diverse artistic currents and the opportunity to exhibit his work to a European audience, solidifying his place within the broader narrative of modern art. His time abroad was essential for refining his vision and gaining wider recognition.

A Unique Style: Memory, Color, and Modernism

Pedro Figari's artistic style is a distinctive fusion of early Modernist sensibilities, particularly influenced by French Post-Impressionism, and a deep connection to the folk traditions and specific cultural landscape of Uruguay and the Río de la Plata region. While acknowledging the technical innovations of European masters like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, whose work he admired, Figari forged a path uniquely his own, rooted in personal experience and national identity.

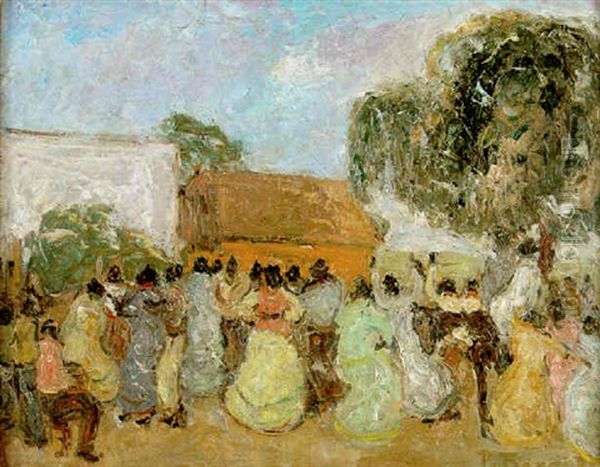

A defining characteristic of Figari's method was his reliance on memory. He rarely painted from direct observation or preliminary sketches. Instead, he drew upon his recollections, particularly vivid memories from his childhood and youth in Montevideo. This approach imbues his paintings with a nostalgic, dreamlike quality, less concerned with photographic accuracy than with evoking a specific atmosphere, emotion, or the essence of a past moment. His canvases become windows into a remembered world.

Color is paramount in Figari's work. He employed a rich, vibrant palette, often using warm tones and bold contrasts to convey energy and emotion. His application of paint, sometimes described as having Impressionist or Post-Impressionist affinities, involved visible brushstrokes and a focus on light, but his use of color often pushed beyond naturalism towards a more expressive and symbolic register. Artists like Pierre Bonnard and Édouard Vuillard explored intimate scenes with rich color, and while Figari's subjects were different, a similar sensitivity to color's emotive power can be felt.

His style navigates a fascinating space between realism and suggestion, observation and invention. Figures are often simplified, their forms captured with fluid lines, contributing to the sense of movement and spontaneity in his scenes. He masterfully balanced narrative detail with a broader, almost abstract handling of composition and color, creating works that are both accessible and deeply personal, resonating with a specific sense of place while touching upon universal human experiences.

Chronicling Uruguayan Life: Themes and Subjects

Figari's paintings serve as an invaluable chronicle of Uruguayan life, history, and culture, particularly focusing on the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He turned his gaze towards the everyday rituals, social gatherings, and traditional customs that defined the identity of his homeland, often depicting scenes that were fading even as he painted them. His work preserves a vision of Uruguay's past with affection and insight.

One of his most recurrent and celebrated themes is the Candombe, the traditional Afro-Uruguayan music and dance form. Works like Candombe or Candombe bajo la luna (Candombe under the Moon) capture the rhythmic energy and communal spirit of these gatherings. Figari depicted the Black communities of Montevideo with sensitivity and dignity, portraying their dances, social life, and presence within the broader Uruguayan tapestry, offering a vital counter-narrative to often-ignored histories.

The figure of the Gaucho, the iconic horseman of the South American plains, also features prominently in his work. Figari depicted their rural life, their skills, and their place in the national imagination. Alongside Gauchos, he painted scenes of Creole society, capturing the atmosphere of colonial-era patios, tertulias (social gatherings), dances like the pericón, and intimate domestic moments, such as the ritual of drinking mate, as seen in Tea; El Mate.

Festivals and public events provided rich subject matter. His painting Carnaval (Carnival) exemplifies his ability to capture the vibrant, theatrical, and sometimes mysterious atmosphere of popular celebrations. He also painted landscapes, like Flor silvestre (Wildflower), reflecting the specific character of the Uruguayan countryside. Works like El patio (The Courtyard/Patio), depicting bustling market scenes or quiet domestic courtyards, further showcase his dedication to capturing the diverse facets of local life.

Figari the Educator: Reform and Influence

Pedro Figari's commitment to education was profound and transformative, particularly his tenure as the director of the National School of Arts and Crafts (Escuela Nacional de Artes y Oficios) in Montevideo from 1915 to 1917. During this relatively brief period, he implemented revolutionary reforms that fundamentally reshaped Uruguayan art and industrial education, leaving a lasting impact.

Figari's approach was humanistic and progressive. He abolished corporal punishment, a common practice at the time, fostering an environment of respect and encouragement. He advocated for open enrollment, making education more accessible, and dismantled the rigid, lengthy traditional curriculum. In its place, he introduced a more flexible, practical, and diverse system where students could choose courses based on their individual interests and aptitudes.

Central to his educational philosophy was the integration of art and industry with local culture and resources. He encouraged students and teachers to draw inspiration from Uruguay's natural environment, its history, and its folk traditions. This emphasis on national identity aimed to create art and design that were authentically Uruguayan, moving away from mere imitation of European models. His leadership saw a significant increase in student enrollment and creative output from the school.

His influence extended beyond the classroom walls. Figari believed in broadening students' cultural horizons, reportedly taking them on visits to museums, including institutions as significant as the Prado Museum in Madrid during his travels, to deepen their understanding of art history. His interest in pedagogical methods was also international; he studied and commented on the educational work of figures like the French Cubist painter and teacher André Lhote, demonstrating his engagement with contemporary educational ideas across borders.

Connections and Collaborations: Weaving into the Art World

Throughout his artistic career, particularly during his time in Buenos Aires and Paris, Pedro Figari actively engaged with fellow artists, writers, and cultural institutions. He was not an isolated figure but participated in the dialogues and movements of his time, contributing to and drawing from the rich artistic environments he inhabited.

In Buenos Aires, his 1921 Müller Gallery exhibition marked his public debut as a dedicated painter. He became involved with the local art scene, connecting with artists whose names are perhaps less internationally known today, such as Sayer and Blaschka. A significant contribution was his role as a co-founder of the influential Asociación Amigos del Arte in 1924, a society dedicated to promoting modern art and culture in Argentina.

His participation extended to exhibitions beyond his solo shows. In 1932, he represented Uruguay in an exhibition reportedly titled "Artistas del Amor" (Artists of Love), submitting four works to the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art. This indicates his growing international profile and his role as a cultural ambassador for his country.

In Paris, Figari's 1925 exhibition at the prestigious Galerie Drouet was a critical success, earning him acclaim from French critics and solidifying his international reputation. He interacted with the vibrant Parisian art world, which included countless influential figures. While specific collaborations mentioned in sources like "Pertuela Cabria (Pablo)" remain unclear, it's certain he was exposed to the currents of Surrealism, Cubism, and other avant-garde movements, engaging with the milieu that included giants like Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró. He also participated in initiatives like an Argentine-Uruguayan Modern Art Salon.

Figari also maintained connections with the literary world. He reportedly collaborated with the renowned Argentine writer José Hernández (author of the epic poem Martín Fierro), revisiting a project to create illustrations for this seminal work of Gaucho literature. (Note: Some sources mention Juan José Hernández, a later writer, but the connection to Martín Fierro strongly suggests José Hernández). His engagement spanned multiple artistic disciplines.

Back in Uruguay, Figari continued to play an institutional role. In 1934, he served as Chairman of the National Fine Arts Commission (Comisión Nacional de Bellas Artes) and was instrumental in organizing the first National Salon of Fine Arts. His deep connections within the Uruguayan and broader Latin American art scenes were evident throughout his career. He was a contemporary of other key Uruguayan modernists like Joaquín Torres-García and Rafael Barradas, whose explorations of constructivism and vibrant modernism, respectively, formed part of the rich artistic landscape Figari contributed to. His work also resonates within the broader context of Latin American modernism, alongside figures like Brazil's Tarsila do Amaral or Mexico's Diego Rivera, who similarly sought to forge modern artistic languages rooted in national identity, though their styles differed greatly. Even echoes of artists like Paul Gauguin, in the search for authentic, non-European subject matter and expressive color, might be considered, though Figari's focus remained firmly on his own culture.

Major Exhibitions and Enduring Legacy

Pedro Figari's work was showcased in numerous important exhibitions during his lifetime and posthumously, cementing his reputation both in South America and Europe. These exhibitions were crucial in establishing his significance and bringing his unique vision of Uruguayan life to a wider audience. His presence in major public collections further attests to his lasting importance.

Key exhibitions during his active years as a painter include his 1921 debut at the Müller Gallery in Buenos Aires, the 1924 exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Arts (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes) in Montevideo, and the highly successful 1925 solo show at Galerie Drouet in Paris. The latter was particularly instrumental in gaining international critical acclaim. An exhibition in 1928, reportedly at a Florida gallery ("Sinduda" mentioned in sources, though the name is uncertain), where his work occupied three rooms, highlighted his prolific output and thematic consistency.

His final years saw continued recognition. His role in organizing the first Uruguayan National Salon in 1934 was significant. Shortly before his death in 1938, a major retrospective exhibition of his work was held in Montevideo, celebrating his contribution to the nation's art. These events underscored his status as a leading figure in Uruguayan modernism.

Today, Figari's paintings are held in prestigious museum collections worldwide. In Uruguay, the Museo Nacional de Artes Visuales in Montevideo holds a significant collection. In Argentina, the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires also features his work. Internationally, the Museo de Arte de las Américas (Art Museum of the Americas) in Washington D.C. holds important pieces like El patio. His works appear regularly at major auction houses, demonstrating continued market interest and appreciation.

Figari's legacy extends far beyond his canvases. He is considered a pioneer of Latin American Modernism, one of the first artists in the region to successfully synthesize European modernist techniques with distinctly local subject matter and perspectives. His focus on memory, identity, and the cultural tapestry of Uruguay helped shape a sense of national artistic identity. His evocative depictions of Candombe, Gaucho life, and Creole society remain powerful and cherished images, offering insight into a specific time and place while resonating with universal themes of community, tradition, and the passage of time. He remains an inspiration for subsequent generations of Latin American artists.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Pedro Figari's journey from distinguished lawyer and public servant to celebrated painter is remarkable. His late dedication to art unleashed a torrent of creativity, resulting in a body of work that is both deeply personal and profoundly representative of his nation's cultural heritage. His unique style, born from memory and rendered in vibrant color, captured the spirit of Uruguay – its landscapes, its people, its traditions, and its history – with unparalleled warmth and insight.

He masterfully blended influences from European Post-Impressionism with his own intimate knowledge of Uruguayan life, creating a modern art that was authentically Latin American. His work stands as a testament to the richness of Creole and Afro-Uruguayan culture, preserving scenes and customs with an evocative power that transcends mere documentation. As an educator, he championed reforms that fostered national identity and practical skills, leaving an indelible mark on Uruguayan art education.

Through his paintings, his writings, and his public life, Pedro Figari offered a singular vision of his world. He remains a pivotal figure in 20th-century art, celebrated for his unique aesthetic, his dedication to his cultural roots, and his role in defining a modern artistic identity for Uruguay and Latin America. His work continues to enchant viewers with its vibrant energy, its nostalgic charm, and its enduring celebration of human life.