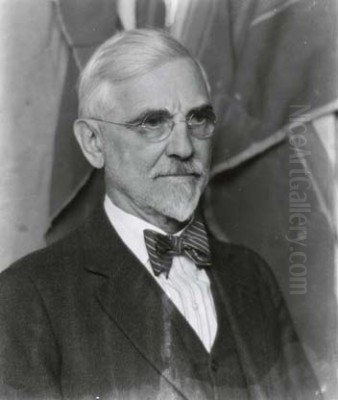

Joseph Henry Sharp stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of American Western art. Born during a time of immense change for the nation and its indigenous populations, Sharp dedicated his long and prolific career to documenting the lives, cultures, and landscapes of Native American peoples, particularly those of the Plains and the Southwest. His work, characterized by its detailed realism and empathetic portrayal, provides an invaluable visual record of cultures undergoing profound transformation. As a founding member of the influential Taos Society of Artists, Sharp not only shaped the artistic identity of the American West but also contributed significantly to the broader narrative of American art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Joseph Henry Sharp was born on September 27, 1859, in Bridgeport, Ohio, to Irish immigrant parents. His childhood was marked by a near-drowning accident that resulted in permanent and profound hearing loss. This challenge, however, did not dampen his innate passion for art. From a young age, Sharp displayed a remarkable talent for drawing. Recognizing and nurturing this gift, his mother supported his artistic ambitions, enabling him to enroll at the McMicken School of Design in Cincinnati.

His deafness shaped his way of interacting with the world. He became adept at lip-reading and often carried a writing pad to facilitate communication. Rather than viewing his hearing loss as an insurmountable obstacle, Sharp approached it with resilience and optimism, qualities that would define his character and career. His early training in Cincinnati laid the foundation for his technical skills, preparing him for more advanced studies abroad.

European Training and Technical Mastery

In 1881, seeking to refine his craft further, Sharp embarked on the first of several trips to Europe, a common path for ambitious American artists of his generation. He immersed himself in the rigorous academic traditions of the continent, studying initially at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. There, under instructors like Charles Verlat, he honed his drawing and painting skills.

His quest for knowledge subsequently took him to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, Germany, where he studied with artists such as Carl von Marr. Munich was a major center for realistic painting, and Sharp absorbed the techniques and philosophies prevalent there. He also spent significant time in Paris, studying at the prestigious Académie Julian and working alongside fellow American expatriate artist Frank Duveneck, who became a mentor and friend. His European sojourns exposed him to Realism, historical painting, and sophisticated portraiture techniques, including wet-on-wet painting and careful canvas preparation, all of which profoundly influenced his developing style.

The Call of the West: Taos and a Defining Vision

A pivotal moment in Sharp's artistic journey occurred in 1883 during his first trip to the American West. He visited Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and other locations in New Mexico, but it was the remote, high-desert village of Taos that captured his imagination. The dramatic landscapes, the unique quality of light, and, most importantly, the enduring presence of the Taos Pueblo Indians resonated deeply with him. This initial encounter sparked a lifelong fascination.

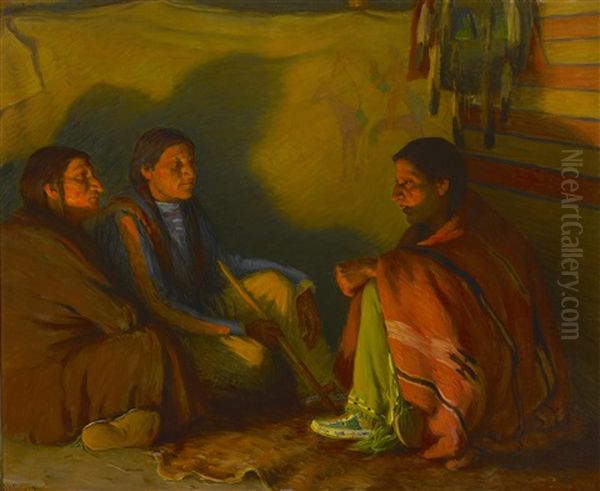

Sharp recognized that the traditional ways of life of Native American communities were rapidly changing due to westward expansion and government policies. He felt a compelling urge to document these cultures before they disappeared entirely. This mission became the driving force behind his art. He saw his work not just as artistic expression but as a form of historical preservation, a way to capture the dignity, traditions, and humanity of his subjects. Taos, with its ancient pueblo and vibrant cultural life, became central to this vision.

Settling in Taos: The Artist and His Studio

Although his initial visits were intermittent due to teaching obligations in Cincinnati and further European travel, Sharp's connection to Taos deepened over time. He eventually purchased a former Penitente chapel in 1893, establishing a permanent base in the community that would become synonymous with his name. He later built a studio home nearby, designed to accommodate his painting needs and house his growing collection of Native American artifacts.

His Taos studio, sometimes referred to as "Absarokee Hut" (a name also associated with his later Montana studio), became a hub of artistic activity. Here, surrounded by the objects and inspirations central to his work, he created many of his most iconic paintings. He developed close relationships with members of the Taos Pueblo, often persuading them to pose for portraits and genre scenes. His respectful approach and genuine interest facilitated a level of trust and collaboration crucial for the authenticity he sought in his depictions.

The Taos Society of Artists: A Collective Vision

Sharp's enthusiasm for Taos was infectious. He shared his experiences and sketches with fellow artists, notably Ernest Blumenschein and Bert Geer Phillips, whom he met while studying in Paris. Inspired by Sharp's accounts, Blumenschein and Phillips made their own fateful journey to Taos in 1898. A broken wagon wheel led them to stay longer than planned, cementing their own connection to the place.

These artists, along with Sharp and others like E. Irving Couse, Oscar E. Berninghaus, and W. Herbert Dunton (often referred to collectively as the "Taos Founders" or the "Taos Six"), recognized the unique artistic potential of the region. In 1915, they formally established the Taos Society of Artists (TSA). Sharp, often considered the "Spiritual Father" of the group due to his early arrival and influence, was a charter member. The TSA aimed to promote the art of its members through traveling exhibitions, bringing national attention to Taos and establishing it as a major American art colony.

Beyond Taos: Winters in Montana and Ethnographic Work

While Taos remained his primary base for many years, Sharp's dedication to documenting Native American life extended beyond the Southwest. Beginning around 1902, he started spending winters at the Crow Agency in Montana, near the site of the Battle of Little Bighorn. President Theodore Roosevelt granted him permission to build a cabin and studio on the battlefield reservation, which he also called "Absarokee Hut." This allowed him unprecedented access to the Crow, Cheyenne, and Sioux peoples.

During these Montana winters, Sharp produced an extraordinary body of work, focusing particularly on portraits of warriors and elders who had lived through periods of significant conflict and cultural change. His efforts were significantly boosted by a major commission from Phoebe A. Hearst (mother of William Randolph Hearst), who funded his work in exchange for paintings for the University of California's anthropology museum (now the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology). This commission enabled him to paint numerous portraits of prominent Native American individuals. He also amassed a substantial personal collection of Native American artifacts, clothing, and utilitarian objects, many of which appear in his paintings, adding layers of authenticity.

Prolific Output and Artistic Style

Joseph Henry Sharp was exceptionally prolific. Over his lifetime, he is credited with creating over 10,000 works, encompassing oil paintings, watercolors, pastels, monotypes, and etchings. His subjects ranged from intimate portraits and multi-figure genre scenes to still lifes featuring Native artifacts and evocative landscapes capturing the unique light and atmosphere of the West.

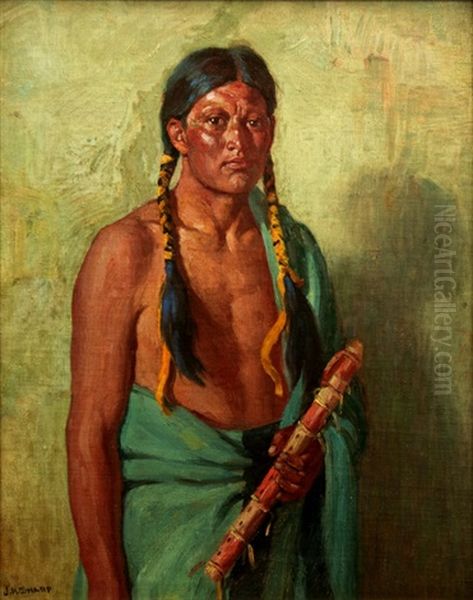

His style remained rooted in the academic Realism he mastered in Europe, characterized by meticulous draftsmanship, accurate rendering of detail, and a rich, often vibrant, color palette. However, his work also shows subtle influences from Impressionism, particularly in his handling of light and atmosphere in landscapes and outdoor scenes. He was deeply interested in capturing the specific textures of fabrics, beadwork, feathers, and weathered skin, lending a tactile quality to his paintings. Above all, his work conveys a sense of dignity and humanity in his subjects, avoiding the stereotypes prevalent in some other Western art of the era. His commitment was to portrayal, not caricature.

Representative Masterpieces

Sharp's vast oeuvre includes numerous works that are considered masterpieces of Western American art. The War Bonnet Maker depicts an elder carefully crafting a traditional feathered headdress, highlighting artistry and cultural continuity. Blackfoot Prayer (likely related to works depicting Plains tribes) captures a moment of spiritual reverence within the natural landscape. Prayer to the Spirit of a Buffalo reflects the deep connection between Plains cultures and the bison, central to their traditional way of life.

The Dance of the Harvest Moon portrays a communal ceremony, emphasizing the cultural richness and social cohesion of Pueblo life. The Peace Maker likely depicts a figure involved in diplomacy or council, suggesting themes of leadership and resolution. His portraiture, such as Young Warrior of the Crow Tribe and the highly valued Chief White Grass, Blackfoot, showcases his skill in capturing individual likeness and character, often working closely with his sitters to ensure accuracy and respect. Jerry Taos with Lover's Flute focuses on a specific individual and cultural practice, while landscape-oriented works like The Prairie (often depicting scenes with figures and animals) convey the vastness and character of the Western environment.

Connections, Contemporaries, and Influence

Sharp's artistic network was extensive. His closest colleagues were the members of the Taos Society of Artists: Ernest Blumenschein, Bert Geer Phillips, E. Irving Couse, Oscar E. Berninghaus, and W. Herbert Dunton. He also maintained connections with his European teachers like Frank Duveneck, Charles Verlat, and Carl von Marr, and likely encountered other prominent artists during his studies, potentially including figures associated with Academic painting like Jean-Léon Gérôme.

Within the broader context of Western American art, Sharp's work can be seen alongside that of contemporaries like Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, who also depicted Western scenes and Native American life, though often with a greater emphasis on dramatic action and narrative. Sharp's focus was generally more ethnographic and portrait-driven. His work builds upon the earlier traditions of artists who documented Native American cultures, such as George Catlin and Karl Bodmer, but with the techniques and sensibilities of late 19th and early 20th-century Realism. His patron, Phoebe A. Hearst, connected him to the world of anthropology and museum collection. The success of the TSA, which he helped found, influenced subsequent generations of artists drawn to the Southwest.

Arts and Crafts Ethos

Sharp also embodied aspects of the Arts & Crafts movement, particularly evident in the construction and furnishing of his studios, especially the Absarokee Hut in Montana. This movement, which originated in Britain and gained traction in America, emphasized craftsmanship, the use of natural materials, and integrated design. Sharp's cabin, filled with handcrafted furniture and Native American objects, reflected this ethos, creating a harmonious environment that was both a workspace and a reflection of his artistic values. This integration of art, craft, and life resonated with the movement's ideals of finding beauty and meaning in the handmade and the authentic.

Legacy, Recognition, and Market Value

Joseph Henry Sharp achieved significant recognition during his lifetime and his reputation has endured. His work was exhibited widely, including important showings at the Paris Salon of 1900 and exhibitions in Washington D.C. the same year, which marked significant breakthroughs in his career. His paintings were acquired by major collectors and institutions.

Today, his works are held in numerous prestigious museum collections, including the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma (which holds the largest collection of his work), the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the aforementioned Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, among others.

Sharp's paintings command high prices in the art market, reflecting his historical importance and artistic skill. Recent auction results, such as the $892,500 achieved for Chief White Grass, Blackfoot in 2024, and consistent strong prices for other major works, underscore his status as a blue-chip artist in the Western American art category. His work is sought after by both private collectors and public institutions.

Enduring Importance

Joseph Henry Sharp passed away on August 29, 1953, in Pasadena, California, at the age of 93, although his artistic heart remained in Taos and the West. He left behind an unparalleled visual legacy. His dedication to documenting Native American life, undertaken with sensitivity and artistic integrity, provides an invaluable resource for understanding a critical period in American history. His role in founding the Taos Society of Artists was instrumental in establishing the Southwest as a vital center for American art.

Despite the challenge of profound deafness, Sharp forged a remarkable career, demonstrating immense talent, dedication, and resilience. He remains celebrated not only for his technical skill and aesthetic achievements but also for his role as a crucial chronicler of the American West and its first peoples, ensuring their stories and likenesses endure through the power of his art.