Eero Nikolai Järnefelt stands as a pivotal figure in the Golden Age of Finnish Art, a period roughly spanning from the 1880s to the early 1910s when Finnish national identity found powerful expression through culture. Born on November 8, 1863, in Vyborg (Viipuri), then part of the Grand Duchy of Finland within the Russian Empire, Järnefelt dedicated his life to capturing the essence of his homeland and its people through the lens of Realism. His meticulous technique, profound empathy for his subjects, and deep connection to the Finnish landscape established him as one of the nation's most respected and beloved painters and art educators. His career bridged the transition from 19th-century academic traditions to a distinctly Finnish modern artistic expression.

Järnefelt's legacy is built upon his masterful landscapes, insightful portraits, and compelling depictions of rural life, often imbued with a quiet dignity and a subtle social awareness. He navigated the artistic currents flowing from St. Petersburg and Paris, adapting international styles like Naturalism and Plein Air painting to suit his Finnish subjects and temperament. More than just a painter, he was an active participant in the cultural life of Finland, closely associated with leading figures in music and literature, and played a significant role in shaping the country's artistic institutions. This exploration delves into the life, influences, artistic style, key works, and enduring impact of Eero Järnefelt, a true master of Finnish Realism.

Aristocratic Roots and Early Artistic Inclinations

Eero Järnefelt hailed from a prominent Fenno-Swedish family deeply embedded in the cultural and administrative life of the Grand Duchy. His father, General August Alexander Järnefelt, was a respected military officer, topographer, and later a governor and senator, known for his strong Fennoman (pro-Finnish language and culture) leanings despite his Swedish-speaking background. His mother, Baroness Elisabeth Järnefelt (née Clodt von Jürgensburg), was of Baltic German and Russian aristocratic descent, belonging to a family renowned for its artistic talents – her uncle, Peter Clodt von Jürgensburg, was a celebrated sculptor in St. Petersburg, and her brother, Mikhail Klodt, was a notable landscape painter.

This cultured and influential family environment provided Eero with both intellectual stimulation and crucial support for his artistic pursuits. The Järnefelt home in Helsinki became a significant salon, attracting leading writers, artists, and musicians, fostering an atmosphere where Finnish cultural identity was actively discussed and promoted. This milieu undoubtedly shaped Eero's worldview and his commitment to depicting Finnish life and character. His siblings also achieved prominence: Arvid became a writer and judge, Kasper a critic, and Armas a renowned composer and conductor, who notably became a close friend and brother-in-law to the composer Jean Sibelius.

Initially, Eero considered a career as a schoolteacher, a path perhaps reflecting the family's interest in national enlightenment. However, his innate talent for drawing and painting soon became evident. Encouraged by his family, particularly his mother whose artistic connections were invaluable, and supported by his father despite initial reservations, Eero formally embarked on his artistic training. He enrolled at the Art Society's Drawing School in Helsinki (the precursor to the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts) in 1874, studying there intermittently until 1878 under artists like Adolf von Becker.

Formative Studies: St. Petersburg and Paris

Seeking more advanced training, Järnefelt followed a path common for aspiring Finnish artists of his time: he looked towards the major art centers of Europe. From 1883 to 1886, he studied at the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. This period was crucial for his development. He lived with his maternal uncle, the landscape painter Mikhail Klodt, a member of the influential Peredvizhniki (Wanderers) movement. The Peredvizhniki championed Realism, focusing on depicting the lives of ordinary people and the Russian landscape with social awareness and psychological depth.

Under the influence of Klodt and the broader atmosphere of Russian Realism, exemplified by artists like Ilya Repin and Ivan Shishkin, Järnefelt honed his technical skills and absorbed the principles of depicting subjects truthfully and with empathy. The emphasis on national character and landscape resonated deeply with his own burgeoning interest in Finnish themes. His time in St. Petersburg provided a solid foundation in academic drawing and painting while exposing him to a powerful, socially conscious form of Realism that would inform his later work.

Following his studies in Russia, Järnefelt sought exposure to the latest artistic developments in Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. From 1886, he enrolled at the Académie Julian, a popular private art school that attracted students from across the globe. There, he studied under prominent academic painters like Tony Robert-Fleury and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. However, Järnefelt was perhaps more significantly influenced by the prevailing trends outside the official Salon system, particularly French Naturalism and Plein Air painting.

The work of Jules Bastien-Lepage made a profound impact on Järnefelt, as it did on many artists of his generation, including fellow Finn Albert Edelfelt. Bastien-Lepage combined meticulous, almost photographic detail with the fresh light and color observed from painting outdoors (en plein air), often depicting rural peasant life with unsentimental honesty yet quiet dignity. This approach, along with the broader Realist tradition established by Gustave Courbet, provided Järnefelt with a modern framework for depicting his Finnish subjects with authenticity and atmospheric truth. He embraced painting outdoors, capturing the specific light and nuances of the Finnish landscape.

Establishing a Finnish Realist Voice

Upon returning to Finland in the late 1880s, Järnefelt was equipped with sophisticated technical skills and a clear artistic vision shaped by his experiences in St. Petersburg and Paris. He quickly established himself as a leading proponent of Realism, focusing his attention on the landscapes and people of his native country. He traveled extensively within Finland, particularly drawn to the Savo region and the area around Koli National Park, seeking authentic representations of Finnish nature and rural life.

His style synthesized the detailed observation learned from Russian Realism and the atmospheric sensitivity of French Plein Air painting. Järnefelt developed a distinctive palette, often characterized by cool blues, greens, and greys, perfectly suited to capturing the specific light and mood of the Finnish environment, especially the clear, crisp air and the subtle variations of light during different seasons and times of day. His brushwork was precise and controlled, allowing for fine detail without sacrificing overall atmospheric unity.

Järnefelt became particularly renowned for his depictions of the Finnish national landscape, especially the views from Koli Hill overlooking Lake Pielinen. These landscapes were more than mere topographical records; they were imbued with a sense of national romanticism, representing the perceived purity, strength, and resilience of the Finnish spirit embodied in nature. He shared this interest in Koli with contemporaries like Pekka Halonen and Akseli Gallen-Kallela, though Järnefelt's approach remained grounded in careful observation rather than Gallen-Kallela's more stylized Symbolism.

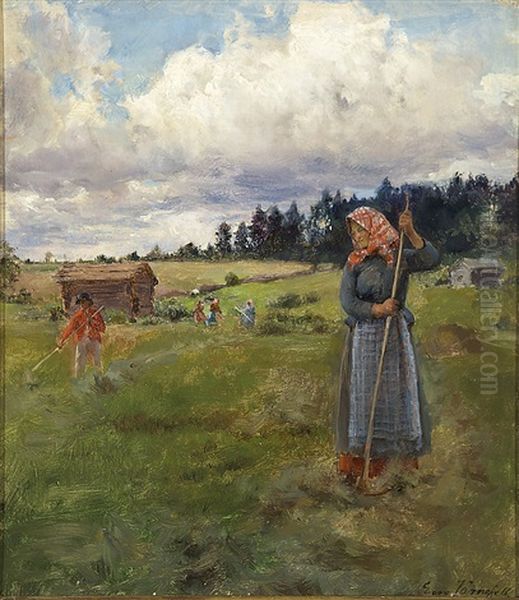

Beyond landscapes, Järnefelt excelled in depicting the lives of ordinary Finns, particularly peasants and rural laborers. Unlike some Realists who focused on the harshness and misery of poverty, Järnefelt often portrayed his subjects with a sense of quiet dignity and inner strength, even when depicting arduous labor. His works avoided overt sentimentality but conveyed a deep empathy and respect for the people whose lives were intrinsically linked to the land.

Masterpiece: Under the Yoke (Burning the Brushwood)

Perhaps Eero Järnefelt's most famous and impactful work is Raatajat rahanalaiset, commonly translated as Under the Yoke or Burning the Brushwood, painted in 1893. This large-scale painting is considered a cornerstone of Finnish Realism and a powerful social statement. It depicts the back-breaking labor of slash-and-burn agriculture, a traditional farming method practiced in eastern Finland where forest land was cleared and burned to create fertile soil for crops, albeit temporarily.

The central figure is a young girl, Johanna Kokkonen, her face smudged with soot, hair matted with sweat, gazing directly at the viewer with an expression of profound exhaustion and perhaps quiet defiance. Her ragged clothes and weary posture speak volumes about the harsh realities of peasant life. Behind her, smoke billows from the burning land, creating a hazy, oppressive atmosphere under a pale sky. The composition is stark, focusing attention on the human element amidst the demanding landscape.

Under the Yoke was groundbreaking in its unvarnished depiction of child labor and rural poverty. While Järnefelt avoided sensationalism, the painting carries a strong social critique, highlighting the hardships faced by the landless rural population. The Finnish title, Raatajat rahanalaiset, translates more literally to "Toilers under Money" or "Wage Slaves," suggesting an economic dimension to their plight, possibly referencing the exploitative conditions under which such labor was often performed.

The painting was exhibited widely and generated significant discussion. Its realism was praised, but its subject matter also provoked discomfort among some segments of society. Nevertheless, it cemented Järnefelt's reputation as a master observer of Finnish life and a painter capable of conveying deep human emotion and social commentary through meticulous technique. The work remains an iconic image in Finnish art history, representing both the harsh realities of the past and the resilience of the Finnish people. Its influence can be seen in the work of later Finnish artists concerned with social themes, such as Juho Rissanen.

Landscapes of Light and Atmosphere

While Under the Yoke showcased his skill in social realism, Järnefelt remained deeply committed to landscape painting throughout his career. He possessed an exceptional ability to capture the unique qualities of Finnish light and atmosphere, from the crisp clarity of winter days to the ethereal glow of Nordic summer nights. His landscapes are characterized by their precision, subtle color harmonies, and profound sense of place.

His numerous paintings of the Koli region are particularly celebrated. Works like Koli Landscape (versions painted throughout his career, e.g., 1915, 1928, 1930) capture the panoramic vistas from the Koli hills, often featuring Lake Pielinen dotted with islands below. Järnefelt rendered the vastness of the space, the texture of the rocks and trees, and the changing effects of light and weather with remarkable fidelity. These paintings became synonymous with the Finnish national landscape, contributing to Koli's status as a symbol of Finnish identity. Unlike the more mythologically charged Koli paintings by Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Järnefelt's interpretations emphasize the natural beauty and serene majesty of the scene.

Järnefelt was also a master of depicting water and reflections. Works like Moonlight in Summer Night (Kesäyön kuu, 1889) or Shore Water (Rantavettä, 1895) showcase his sensitivity to the subtle interplay of light on water surfaces. He captured the stillness of lakes, the gentle ripples, and the way light dissolves and reflects, creating moods ranging from tranquil serenity to melancholic introspection. His use of cool blues, greens, and violets in these scenes perfectly evokes the unique luminosity of the Nordic summer twilight.

His plein air studies, often painted directly from nature on smaller canvases or panels, reveal his commitment to capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. These studies informed his larger studio compositions, ensuring they retained a sense of immediacy and authenticity. Järnefelt's landscapes stand alongside those of contemporaries like Pekka Halonen and Victor Westerholm as defining representations of the Finnish natural environment during the Golden Age.

The Art of Portraiture

Alongside his landscapes and genre scenes, Eero Järnefelt was one of Finland's most sought-after portrait painters. His portraits are admired for their psychological insight, technical refinement, and ability to convey the sitter's personality and social standing without resorting to flattery or excessive formality. He painted numerous prominent figures from Finnish society, including politicians, academics, artists, and members of his own influential circle.

His approach to portraiture was rooted in the Realist tradition, emphasizing accurate likeness and careful attention to detail in clothing and setting. However, his portraits transcend mere photographic representation. He possessed a keen ability to capture the inner life of his subjects through subtle nuances of expression, posture, and gaze. His portraits often have a quiet intensity, suggesting a thoughtful engagement between the artist and the sitter.

Among his notable subjects were leading cultural figures such as the author Juhani Aho (his brother-in-law) and the composer Jean Sibelius (also his brother-in-law, married to Eero's sister Aino). His portraits of family members, including his wife, the actress Saimi Swan, are particularly sensitive and intimate. He also painted numerous official portraits, such as that of University Vice-Chancellor Johan Philip Palmén, demonstrating his ability to fulfill commissions while maintaining his artistic integrity.

Järnefelt's portraits align with the Fennoman ideals prevalent in his circle, aiming to create a gallery of Finnish national figures, documenting the intellectual and cultural elite of the era. This project implicitly served to bolster national self-esteem during a period of increasing Russification pressure. His skill in capturing character made him a chronicler of his time, preserving the likenesses of individuals who shaped modern Finland. His portrait style influenced subsequent Finnish portraitists, setting a high standard for psychological depth and technical execution, comparable in quality to the work of Albert Edelfelt, another master portraitist of the era.

Järnefelt and the Golden Age Circle

Eero Järnefelt was a central figure within the vibrant artistic and cultural milieu of Finland's Golden Age. His family background, education, and marriage connected him to many of the leading lights of the era. The Järnefelt family salon, hosted by his mother Elisabeth, was a crucial meeting point for artists, writers, and musicians who shared a commitment to Finnish culture. This circle included figures like Juhani Aho, Jean Sibelius, Akseli Gallen-Kallela, Pekka Halonen, and others who collectively shaped the nation's artistic identity.

His relationship with Jean Sibelius was particularly close, cemented by Sibelius's marriage to Eero's sister Aino in 1892. The two men shared a deep love for Finnish nature and culture, which informed their respective creative outputs. Järnefelt painted several portraits of the composer, capturing his intense personality. Similarly, his connection to Juhani Aho, who married Venny Soldan-Brofeldt (another prominent artist), placed him at the heart of literary circles. These interconnections fostered a rich cross-pollination of ideas between painting, music, and literature.

Artistically, Järnefelt is often grouped with Akseli Gallen-Kallela and Pekka Halonen as the leading landscape and genre painters of their generation. While all three shared an interest in Finnish nature and national themes, their styles differed. Gallen-Kallela moved towards Symbolism and a more stylized National Romanticism, often drawing inspiration from the Kalevala epic. Halonen focused on serene depictions of winter landscapes and rural life, emphasizing harmony and tranquility. Järnefelt remained most consistently committed to Realism, prioritizing accurate observation and atmospheric truth, though his later work sometimes showed a simplification of form influenced by Synthetist ideas circulating from France, possibly absorbed through colleagues like Magnus Enckell or Ellen Thesleff.

He also interacted with other significant artists of the period, such as the pioneering female painters Helene Schjerfbeck and Maria Wiik, who were also exploring Realism and psychological portraiture. While perhaps less radical in his stylistic evolution than Schjerfbeck or Symbolists like Hugo Simberg, Järnefelt's unwavering dedication to Realism provided a crucial anchor and a standard of excellence within the diverse landscape of Finnish art at the turn of the century.

Academic Role and Later Years

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Eero Järnefelt made significant contributions as an educator and arts administrator. His reputation for technical mastery and his deep understanding of artistic principles made him a natural fit for teaching. In 1902, he began teaching drawing at the University of Helsinki, a position he held for over two decades, until 1928. His patient and methodical approach influenced generations of students, not just aspiring artists but also those in other fields who benefited from training in observation and draftsmanship.

His standing within the Finnish art community was further recognized when he was appointed chairman of the Finnish Art Academy (Suomen Taideakatemia) in 1912, serving in this capacity until 1915, and later held other influential positions within arts organizations. He played an active role in shaping arts policy and promoting Finnish art both domestically and internationally. His own work continued to be exhibited, and he received numerous accolades, including medals at the Paris World Fairs of 1889 and 1900, which helped raise the international profile of Finnish art.

In his later career, Järnefelt continued to paint landscapes and portraits, maintaining his commitment to Realism. While the avant-garde movements of the early 20th century, such as Expressionism and Cubism, gained traction elsewhere in Europe and even among some younger Finnish artists, Järnefelt largely remained true to the principles he had developed earlier. His technique remained meticulous, his observation keen, and his focus centered on the Finnish environment and its people.

He spent considerable time at his family villa, Suviranta, located on Lake Tuusula, near Helsinki. This area became an artists' colony, home to Sibelius, Aho, Halonen, and others, providing a supportive community and continued inspiration from the surrounding nature. Eero Järnefelt continued to work until shortly before his death in Helsinki on November 15, 1937, leaving behind a rich legacy as one of Finland's most accomplished and respected artists.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Eero Järnefelt's contribution to Finnish art is profound and multifaceted. As a leading exponent of Realism, he captured the Finnish landscape and its people with unparalleled accuracy and sensitivity, helping to define a national visual identity during a crucial period of cultural awakening and political uncertainty under Russian rule. His works, particularly Under the Yoke and his Koli landscapes, have become iconic images deeply ingrained in the Finnish national consciousness.

His technical mastery set a high standard for painting in Finland. His ability to render light, atmosphere, and texture, combined with his psychological insight in portraiture, earned him widespread admiration. He demonstrated that Realism could be a powerful vehicle for expressing national character and addressing social issues without sacrificing artistic quality. His dedication to depicting ordinary Finnish life, especially the resilience of rural communities, resonated deeply with the Fennoman ideals of celebrating vernacular culture.

As an educator at the University of Helsinki and a leader in arts organizations, Järnefelt played a vital role in nurturing artistic talent and shaping the institutional framework for the arts in Finland. He influenced countless students through his teaching, emphasizing the importance of strong draftsmanship and careful observation – principles derived from his own rigorous training in St. Petersburg and Paris.

While artistic styles evolved rapidly in the 20th century, Järnefelt's work has retained its power and relevance. His paintings are celebrated not only for their historical significance but also for their enduring aesthetic appeal and emotional depth. He remains a key figure studied in Finnish art history, representing the pinnacle of Realism within the Golden Age. His ability to connect the specific details of Finnish life and landscape to universal human experiences ensures his continued appreciation by audiences both in Finland and internationally. Eero Järnefelt's legacy is that of a master craftsman, a keen observer, and a painter whose art eloquently speaks of the land and people he knew and loved so well.