Pieter Andreas Rysbrack, a notable Flemish painter active during the late Baroque and early Rococo periods, carved a distinct niche for himself, particularly through his detailed landscapes and still life compositions. Born into an artistic dynasty, he navigated the vibrant art scenes of Flanders and, later, England, leaving behind a body of work that offers valuable insights into the aesthetic preferences and cultural exchanges of the 18th century. Though perhaps overshadowed in popular memory by his celebrated sculptor brother, John Michael Rysbrack, Pieter Andreas's contributions, especially his topographical views, remain significant for art historians and enthusiasts of the period.

An Artistic Heritage: The Rysbrack Family

Pieter Andreas Rysbrack was born in Antwerp, likely between 1684 and 1690, into a family deeply embedded in the arts. His father, Pieter Rysbrack (1655–1729), was an accomplished landscape painter in his own right, known for his classical, Italianate scenes reminiscent of artists like Gaspard Dughet and Francisque Millet. This paternal influence undoubtedly shaped Pieter Andreas's early artistic inclinations, providing him with a foundational understanding of landscape composition and technique within the rich Flemish tradition.

The Rysbrack family was a hub of creativity. Beyond his father, Pieter Andreas's younger brother, John Michael Rysbrack (1694–1770), would go on to become one of the most important sculptors working in England during the first half of the 18th century. His monumental works, portrait busts, and funerary monuments, executed with a blend of Baroque dynamism and classical restraint, earned him widespread acclaim. Other siblings also pursued artistic careers, though with less prominence. This familial environment fostered a competitive yet supportive atmosphere, encouraging the development of individual talents while sharing a common artistic language.

Early Career in Flanders

Details of Pieter Andreas Rysbrack's early training are not extensively documented, but it is highly probable that he received his initial instruction from his father. Antwerp, at the time, was still a significant artistic center, though past its golden age zenith of Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck. The city's guilds and workshops continued to uphold strong traditions in various genres, including landscape and still life painting.

Rysbrack's early work would have been steeped in the Flemish Baroque style. This tradition emphasized rich colors, meticulous detail, and often, a sense of abundance and vitality, particularly in still life. Landscape painting, while evolving, often retained elements of the idealized or the picturesque, drawing inspiration from both local scenery and Italianate conventions. Artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder and Younger had long established a high standard for detailed landscapes, while painters such as Jan Fyt and Frans Snyders were masters of the game and fruit still life. Pieter Andreas would have been well-acquainted with these precedents.

His skill in rendering textures, foliage, and atmospheric effects, which became evident in his later English works, was likely honed during these formative years in Flanders. He developed a keen eye for observation and a proficient hand capable of translating the natural world onto canvas with precision and a subtle expressiveness.

The Move to England and the Chiswick House Commission

Around 1720, Pieter Andreas Rysbrack made a pivotal decision to move to London. This was a common path for many continental artists seeking new opportunities, as England, particularly London, was becoming an increasingly wealthy and culturally ambitious center. His brother, John Michael, had already established himself in London by this time, which may have facilitated Pieter Andreas's own relocation and integration into the English art scene.

A significant commission that marked his early career in England came from Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington. Lord Burlington was a leading arbiter of taste, a prominent architect in the Palladian style, and a key figure in the promotion of Neoclassicism in Britain. He commissioned Pieter Andreas Rysbrack to create a series of paintings depicting the gardens of Chiswick House, his influential Palladian villa in West London.

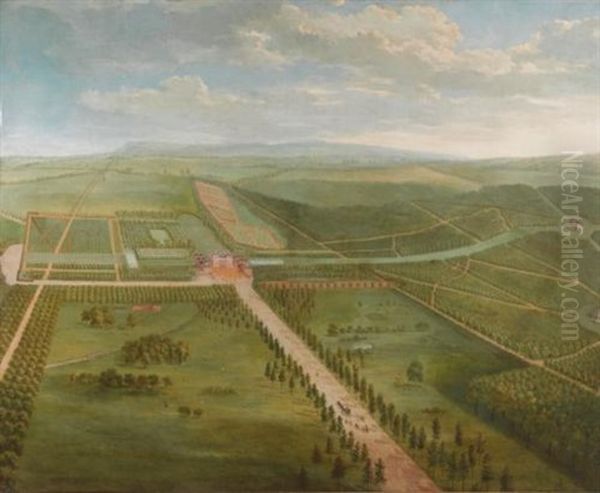

These paintings, executed around 1728-1730, are of immense historical and artistic importance. Chiswick Gardens, designed by Burlington himself with the assistance of William Kent, was at the forefront of the emerging English landscape garden movement. This movement represented a shift away from the formal, geometric garden designs of the French and Dutch traditions towards a more naturalistic, picturesque, and often allegorical style, inspired by classical landscapes and the paintings of artists like Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin.

Rysbrack's views of Chiswick House and its gardens meticulously document the early stages of this transformation. They capture the architectural features, the carefully planned vistas, the newly planted groves, and the classical statuary that adorned the grounds. These works are not merely topographical records; they convey a sense of the evolving aesthetic, capturing the interplay of architecture and nature that was central to Burlington's vision. The paintings served as both a record of achievement and a promotional tool for Burlington's ideas. For Rysbrack, this commission provided significant exposure and aligned him with one of the most influential patrons of the era.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Pieter Andreas Rysbrack's artistic style is characterized by its detailed realism, careful composition, and a somewhat reserved, yet evocative, depiction of his subjects. His Flemish training is evident in the precision of his brushwork and his attention to the textures of foliage, water, and architectural elements.

Landscapes and Topographical Views:

His most recognized contributions are in the realm of landscape and topographical painting. The Chiswick series is a prime example, but he also produced other views of English estates and scenery. These "estate portraits" or "prospects" were popular among landowners who wished to have a visual record of their properties and their improvements. Rysbrack's approach was typically straightforward and descriptive, aiming for accuracy while still imbuing the scene with a sense of order and tranquility.

His landscapes often feature a clear, even light, and a carefully structured composition that leads the viewer's eye through the scene. While not as overtly romantic or dramatic as the landscapes of later generations, such as those by J.M.W. Turner or John Constable, Rysbrack's works possess a quiet charm and provide invaluable documentation of 18th-century English environments. He can be seen as a precursor to a more developed school of English landscape painters, including figures like George Lambert, Samuel Scott, and Richard Wilson, who further explored the depiction of native scenery.

Still Life Paintings:

Rysbrack also continued the Flemish tradition of still life painting. His works in this genre, such as the notable Game Still-Life, showcase his skill in rendering the varied textures of fur, feathers, fruit, and foliage. These compositions are typically well-balanced, with a rich palette and a meticulous attention to detail that invites close inspection. Such paintings often carried symbolic meanings related to abundance, the hunt, or the transience of life, themes common in the still life tradition stemming from artists like Jan Weenix or Melchior d'Hondecoeter. His still lifes demonstrate a technical mastery and an understanding of the genre's conventions, reflecting the enduring appeal of such subjects for collectors.

Representative Works

Several works stand out in Pieter Andreas Rysbrack's oeuvre, illustrating his skills and thematic concerns:

The Chiswick House Series (c. 1728-1730): This set of eight (or more) views is arguably his most important contribution. Paintings such as A View of the Cascade and Grotto at Chiswick or A View of the Bagnio and the Domed Building at Chiswick are invaluable historical documents. They show the garden at a crucial stage of its development, with features designed by William Kent and Lord Burlington. The clarity and detail in these paintings allow for a precise understanding of the garden's layout and its innovative features, which were influential in the development of the English landscape style.

Game Still-Life: This painting exemplifies his prowess in the still life genre. It typically features an arrangement of hunted game (birds, hares) often combined with fruit or hunting paraphernalia. The work is characterized by its balanced composition, rich textures, and the lifelike rendering of the animals. Such pieces were popular for dining rooms and reflected the status and leisure pursuits of the gentry. The precision here echoes the work of earlier Flemish masters like Adriaen van Utrecht.

Prospect of Tottenham Park, Wiltshire (c. 1730s-1740s): This work, depicting the estate of Lord Bruce (later Earl of Ailesbury), is another example of his topographical landscape painting. It showcases the sprawling parkland, the mansion, and the surrounding countryside. Such paintings served not only as decorative pieces but also as statements of land ownership and social standing. The detailed rendering of the estate and its features would have been highly valued by the patron.

These works highlight Rysbrack's ability to adapt his Flemish training to the demands and tastes of the English market, particularly in the burgeoning field of topographical landscape painting.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

In England, Pieter Andreas Rysbrack operated within a vibrant artistic community that included both native-born and immigrant artists. His most direct artistic connection was, of course, with his brother, John Michael Rysbrack, whose success as a sculptor may have provided Pieter Andreas with introductions to potential patrons.

The commission from Lord Burlington also placed him in the orbit of William Kent, a versatile architect, garden designer, painter, and furniture designer. While Rysbrack was documenting Kent's garden designs at Chiswick, Kent himself was a key figure in popularizing the Palladian style and the new English landscape garden.

Rysbrack is also known to have collaborated with other artists. For instance, he worked with the French engraver and painter Jacques Rigaud, who also specialized in topographical views of English estates and gardens. Such collaborations were common, with painters creating original views that were then engraved for wider distribution, popularizing images of notable sites.

The English art scene at the time was diverse. In landscape, artists like John Wootton were known for their sporting scenes and classical landscapes, while Peter Tillemans, another Flemish émigré, produced topographical views, battle scenes, and sporting art. George Lambert was emerging as one of the first significant native-born English landscape painters. In portraiture, figures like Sir Godfrey Kneller (though his career was ending as Rysbrack's began in England) and later, William Hogarth (who also worked in narrative scenes) and Thomas Hudson, were prominent. The context for still life painting included artists like Luke Cradock, known for his bird paintings.

Pieter Andreas Rysbrack's work, therefore, fits into a broader European tradition being adapted and developed in England. His meticulous, descriptive style in landscape found a ready market among landowners, contributing to a genre that would see further development with artists like Canaletto (during his English period) and later, Paul Sandby, often called the "father of English watercolour."

Later Career and Legacy

Information about Pieter Andreas Rysbrack's later career is less prominent than that of his early successes in England. He continued to paint landscapes and still lifes, but he did not achieve the same level of fame or influence as his brother, John Michael. This is not uncommon; the art world often elevates certain genres or individuals, and sculpture, particularly monumental and portrait sculpture, held a significant status.

Pieter Andreas Rysbrack died in London in October 1748 and was buried at St. Marylebone. His will indicates a modest but comfortable financial standing.

His legacy is primarily tied to his topographical views, especially the Chiswick series. These paintings are invaluable for garden historians and scholars of 18th-century English culture. They provide a visual record that complements written descriptions and architectural plans, offering a more tangible sense of these designed landscapes. His work demonstrates the important role that Flemish artists continued to play in the English art scene, bringing with them skills and traditions that enriched British art.

While he may not be a household name like some of his contemporaries, Pieter Andreas Rysbrack's contribution is significant. He was a skilled practitioner of his craft, a diligent observer of nature and architecture, and his paintings offer a window into the aesthetic sensibilities of Georgian England. His work underscores the importance of topographical painting as both an art form and a historical document, capturing the appearance of specific places at particular moments in time.

His still lifes, though perhaps less discussed, also demonstrate his adherence to and competence within the strong Flemish tradition. They reflect the enduring appeal of this genre, which celebrated the beauty and bounty of the natural world, rendered with exquisite detail and technical skill.

Conclusion: An Artist of Detail and Documentation

Pieter Andreas Rysbrack stands as a competent and noteworthy artist of the 18th century, whose career bridged the artistic traditions of Flanders and the evolving cultural landscape of Georgian England. Born into an artistic family, he developed a meticulous style well-suited to both still life and landscape painting. His move to England brought him significant commissions, most notably from the Earl of Burlington for the Chiswick House series, which remains his most celebrated achievement. These paintings are not only aesthetically pleasing but are crucial documents for understanding the birth of the English landscape garden movement.

Working alongside and in the context of artists such as his father Pieter Rysbrack, his brother John Michael Rysbrack, patrons like Lord Burlington, and contemporaries like William Kent, Jacques Rigaud, Peter Tillemans, and George Lambert, Pieter Andreas contributed to the rich tapestry of 18th-century art. His dedication to detailed representation in his topographical views and the skilled execution of his still lifes ensure his place in the annals of art history, particularly as a chronicler of the English scene through a refined Flemish lens. His works continue to be studied and appreciated for their artistic merit and their invaluable contribution to our understanding of the period.