Petrus Christus (c. 1410/1420 – 1475/1476) stands as a significant, if sometimes enigmatic, figure in the rich tapestry of Early Netherlandish painting. Active primarily in Bruges, a bustling commercial and artistic hub, Christus emerged in the wake of the towering genius of Jan van Eyck. While deeply influenced by Van Eyck and other pioneering figures like Robert Campin and Rogier van der Weyden, Christus forged a distinct artistic identity characterized by innovation in perspective, a refined sensitivity in portraiture, and a quiet, contemplative mood that pervades his religious and secular works. His contributions were crucial in bridging the first generation of Early Netherlandish masters with later developments in the 15th century, and his influence, though perhaps not as overtly widespread as Van Eyck's, was nonetheless palpable, extending even to artistic centers in Italy.

The Bruges Context and Christus's Emergence

The Bruges in which Petrus Christus established his career was one of Europe's most prosperous cities during the 15th century. As a vital center of trade under the Dukes of Burgundy, it attracted merchants, bankers, and artisans from across the continent, including a significant Italian expatriate community. This cosmopolitan environment fostered a vibrant artistic market, with patrons eager for devotional paintings, altarpieces, and increasingly, personal portraits. The city had already been graced by Jan van Eyck, who served as court painter to Philip the Good and resided in Bruges until his death in 1441. The artistic standards were thus exceptionally high.

Petrus Christus is believed to have been born in Baarle, near Breda, a region on the border of modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands. The exact date of his birth is uncertain, with estimates ranging from 1410 to 1420. The first concrete record of his presence in Bruges dates from July 6, 1444, when he purchased his citizenship. This act was a prerequisite for establishing an independent workshop and joining the painters' guild. The timing, just three years after Van Eyck's death, has led to considerable speculation about a possible connection between the two artists. Some scholars propose that Christus may have arrived in Bruges earlier and worked in Van Eyck's workshop, perhaps even completing some of his master's unfinished commissions. While direct documentary proof is lacking, stylistic affinities in Christus's early works lend credence to this theory.

Upon becoming a free citizen, Christus quickly established himself as one of Bruges's leading painters. His workshop would have produced a range of works, from small devotional panels for private contemplation to more ambitious altarpieces and portraits. He seems to have catered to a diverse clientele, including local burghers, clergy, and foreign merchants, particularly those from Italy and Spain, who appreciated the meticulous realism and luminous oil technique characteristic of Netherlandish painting.

Artistic Lineage and Influences

The art of Petrus Christus is deeply rooted in the innovations of the first generation of Early Netherlandish painters. His most profound debt is undoubtedly to Jan van Eyck (c. 1390–1441). From Van Eyck, Christus inherited a mastery of the oil medium, allowing for rich colors, subtle gradations of light and shadow, and an astonishing level of detail. Works like Christus's Portrait of a Carthusian (1446) echo Van Eyck's penetrating realism and his ability to capture the tangible presence of the sitter. The meticulous rendering of textures, from the monk's habit to the fly seemingly resting on the painted frame (a trompe-l'œil device Van Eyck also employed), speaks to this Eyckian heritage. There's also a shared interest in complex interior spaces and the play of light within them.

Another foundational figure whose influence can be discerned is Robert Campin (c. 1375–1444), often identified with the Master of Flémalle. Campin, active in Tournai, was a pioneer in depicting religious scenes with a new sense of domestic realism and robust, sculptural figures. While Christus's figures are generally more slender and elegant than Campin's, the older master's emphasis on tangible reality and everyday settings for sacred events likely resonated with Christus.

Rogier van der Weyden (c. 1399/1400–1464), a contemporary of Christus who was primarily active in Brussels but whose fame was widespread, also left an imprint. Van der Weyden was renowned for his emotionally charged compositions and the graceful, often sorrowful, expressions of his figures. Christus's Lamentation (c. 1450s), for example, while possessing its own quiet dignity, shows an awareness of Van der Weyden's powerful interpretations of this theme, particularly in the expressive postures and pathos of the figures. However, Christus generally tempered Van der Weyden's dramatic intensity with a more restrained and introspective mood.

It is important to note that Christus was not merely an imitator. He absorbed these influences and synthesized them into a personal style that was both innovative and forward-looking. He built upon the foundations laid by these masters, particularly in his exploration of perspective and spatial coherence.

Innovations in Perspective and Spatial Construction

One of Petrus Christus's most significant contributions to Northern European painting was his sophisticated understanding and application of linear perspective. While Italian artists like Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti were codifying the principles of geometric perspective in Florence, Christus appears to have independently, or through an awareness of these developments (perhaps via Italian merchants in Bruges), explored similar concepts.

He is often credited as one of the first Netherlandish painters to consistently employ a rational, single-vanishing-point perspective system to create a unified and measurable pictorial space. This is evident in works like The Annunciation and Nativity (c. 1452, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) or the interior setting of A Goldsmith in his Shop, possibly Saint Eligius (1449, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). In these paintings, the architectural elements and floor tiles recede convincingly towards a central vanishing point, creating a sense of depth and order that was novel in Northern art. This contrasts with the more empirical, less systematic approach to space often seen in the works of Van Eyck or Campin, who achieved convincing depth through observation and atmospheric effects rather than strict geometric construction.

Christus's use of perspective was not merely a technical exercise; it served to enhance the narrative clarity and the viewer's engagement with the scene. By creating a believable, three-dimensional world, he invited the viewer to step into the painting, fostering a more intimate connection with the sacred or secular events depicted. This innovation would have a lasting impact, influencing later Netherlandish artists such as Dirk Bouts (c. 1410/1420–1475), a contemporary active in Leuven, who also experimented with rigorous perspective systems.

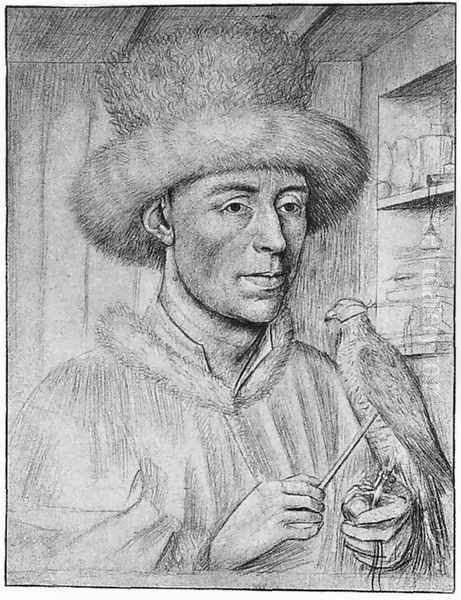

Portraiture: Capturing Interiority

Petrus Christus was a highly accomplished portraitist, and his works in this genre are among his most celebrated. He moved beyond the strictly profile or three-quarter views favored by some of his predecessors, often placing his sitters in specific, albeit usually neutral or simple, interior settings. This approach, seen in works like Portrait of a Man (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) or the iconic Portrait of a Young Girl (c. 1470, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), allowed for a greater sense of presence and psychological depth.

The Portrait of a Young Girl is particularly remarkable for its enigmatic charm and subtle characterization. The girl, whose identity remains unknown, gazes out with a direct, slightly melancholic expression. Christus captures her youth and delicate features with exquisite refinement. The simple dark background and the carefully rendered details of her attire, including the intricate headdress and necklace, focus attention on her face and her introspective mood. This work demonstrates Christus's ability to convey not just a physical likeness but also a sense of the sitter's inner life, a quality that would become increasingly important in portraiture.

His Portrait of a Carthusian (1446, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is another masterpiece. The monk is depicted with stark realism, his gaze intense and thoughtful. The inclusion of the trompe-l'œil fly on the fictive frame is a playful touch that also underscores the artist's skill in creating illusionistic effects. The signature and date on this panel are crucial for establishing Christus's early chronology. These portraits often feature a subtle play of light that models the features softly, contributing to their lifelike quality.

Key Works and Thematic Concerns

Petrus Christus's oeuvre, though not extensive (around thirty works are generally attributed to him), covers a range of subjects, primarily religious scenes and portraits.

A Goldsmith in his Shop, possibly Saint Eligius (1449): This fascinating panel, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is one of Christus's most complex and debated works. It depicts a goldsmith in his workshop, weighing a wedding ring for a sumptuously dressed young couple. The scene is rich in detail, showcasing various objects associated with the goldsmith's trade, such as precious stones, coral, and finished pieces of jewelry. A convex mirror in the foreground reflects two figures outside the shop, a device reminiscent of Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait. For a long time, the central figure was identified as Saint Eligius, the patron saint of goldsmiths. However, more recent scholarship suggests it might be a vocational portrait of a specific goldsmith, perhaps commissioned to commemorate a marriage or as an advertisement for his craft. The painting offers a vivid glimpse into the material culture and commercial life of 15th-century Bruges.

The Lamentation (c. 1450s): Housed in the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, Brussels, this panel depicts the sorrowful scene of Christ's body being mourned after the Deposition. The figures of the Virgin Mary, Saint John, Mary Magdalene, and others are arranged in a balanced composition, their grief expressed with a quiet intensity rather than overt drama. Christus's handling of the figures is somewhat more stylized here, with elongated forms and a focus on linear rhythms, possibly reflecting the influence of Rogier van der Weyden. The landscape background, though detailed, serves primarily as a setting for the emotional core of the scene.

Our Lady of the Dry Tree (c. 1465): This small, jewel-like panel in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, is one of Christus's most unusual and symbolic works. The Virgin and Child are depicted within a barren, thorny tree, from which hang fifteen golden letter 'A's, representing Ave Marias. The imagery is derived from the Confraternity of Our Lady of the Dry Tree, a lay religious brotherhood in Bruges to which Christus and his wife are recorded as belonging. The painting is a testament to the personal piety and devotional practices of the time, and its intricate symbolism would have been readily understood by its original audience.

Annunciation and Nativity Diptych (or two wings of a triptych, c. 1452): These panels in Berlin showcase Christus's skill in narrative and his use of perspective. The Annunciation is set within a meticulously rendered church interior, its architectural lines converging to create a deep and coherent space. The Nativity takes place in a humble shed, with Joseph, Mary, and angels adoring the Christ Child, while a detailed landscape unfolds in the background. The clarity of the spatial organization and the delicate rendering of light are characteristic of Christus's mature style.

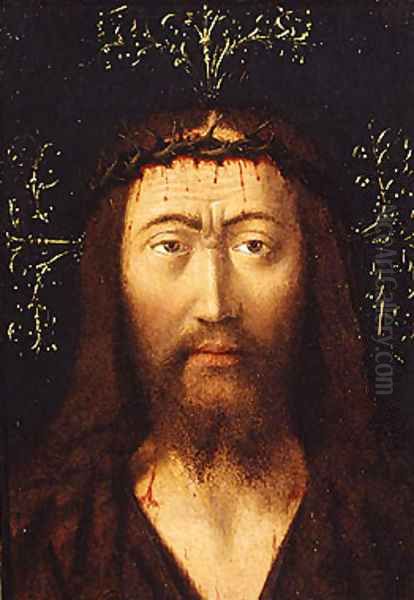

Head of Christ (c. 1445): This intimate portrayal, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, combines elements of the "Vera Icon" (True Image) tradition with the "Man of Sorrows." Christ's face, depicted with great sensitivity and realism, confronts the viewer directly, inviting contemplation of his suffering and divinity. The meticulous rendering of individual strands of hair and beard is typical of Christus's attention to detail.

Other notable works include the Exeter Madonna (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), which shows a strong Eyckian influence, and various portraits of donors and unknown sitters that further attest to his skill in capturing individual likeness and character.

The Bruges School and Contemporaries

Petrus Christus was a central figure in what is often termed the "Bruges School" of painting, which flourished in the mid-to-late 15th century. While not a formal school in the modern sense, Bruges was home to a remarkable concentration of talented artists who often influenced one another.

After the death of Jan van Eyck and the departure of Rogier van der Weyden from Tournai to Brussels, Christus became the leading painter in Bruges for a period. His innovations, particularly in perspective and the naturalistic portrayal of figures in defined spaces, would have been noted by other artists active in the city.

Among his contemporaries in the broader Netherlandish sphere were:

Dirk Bouts (c. 1410/1420–1475): Active in Leuven, Bouts shared Christus's interest in rational perspective and created works of serene, understated piety. His figures often have a distinctive, somewhat gaunt appearance.

Hans Memling (c. 1430/1440–1494): Though German-born, Memling settled in Bruges around 1465 and became immensely successful. His style, characterized by its gentle lyricism, harmonious compositions, and sweet-faced Madonnas, built upon the foundations laid by Van Eyck, Van der Weyden, and to some extent, Christus. Memling's prolific output and appealing style made him one of the most popular painters of his time.

Hugo van der Goes (c. 1430/1440–1482): Active in Ghent and later near Brussels, Van der Goes was a painter of extraordinary emotional power and psychological intensity. His Portinari Altarpiece, sent to Florence, had a significant impact on Italian artists. While his style is more dramatic than Christus's, they were part of the same artistic generation.

Geertgen tot Sint Jans (c. 1460/1465–1490/1495): Active in Haarlem, in the Northern Netherlands, Geertgen developed a distinctive style known for its tender emotion and innovative handling of light, particularly in night scenes.

Other artists like Simon Marmion (active in Valenciennes), Justus van Gent (active in Ghent and Urbino, Italy), and later figures such as Gerard David (who would become the leading painter in Bruges after Memling's death) and Quentin Massys (active in Antwerp, a city that would eventually eclipse Bruges as an artistic center) all contributed to the rich artistic landscape of the 15th and early 16th centuries in the Low Countries. Joachim Patinir, though slightly later, would build on the landscape traditions nascent in earlier Netherlandish works. Jan de Beer and Alaert du Hamel were also part of this broader artistic milieu.

International Connections and Later Career

The international character of Bruges meant that Christus's work was known beyond the Low Countries. Records indicate that he had dealings with Spanish merchants, and it is highly probable that Italian merchants, such as members of the Arnolfini or Portinari families, also commissioned or purchased his paintings. The meticulous realism and luminous oil technique of Netherlandish art were greatly admired in Italy.

There is evidence to suggest that Christus himself may have traveled to Italy, or at least had significant contact with Italian art and artists. Some scholars have pointed to similarities between Christus's work and that of Antonello da Messina (c. 1430–1479), an Italian painter who mastered the oil technique and whose portraits share a certain psychological acuity with those of Christus. It has been hypothesized that Antonello may have encountered Christus's work, or even the artist himself, possibly in Milan or another Italian center. While the exact nature of this connection remains debated, it highlights the cross-currents of artistic exchange between Northern and Southern Europe during this period. The adoption of oil painting by Italian artists like Antonello, and later Leonardo da Vinci and Giovanni Bellini, was partly inspired by the achievements of Netherlandish masters. Even later, the dramatic realism of Caravaggio can be seen as a distant echo of the verisimilitude pioneered in the North.

Christus continued to be active in Bruges throughout his career. He and his wife joined the Confraternity of Our Lady of the Dry Tree in 1462 or 1463, an association that likely brought him commissions, such as the eponymous painting. He is last documented in Bruges in 1473 and is believed to have died there between late 1475 and early 1476.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For centuries after his death, Petrus Christus was a somewhat overlooked figure, overshadowed by the greater fame of Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hans Memling. However, modern art historical scholarship, beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with pioneers like Gustav Friedrich Waagen and Max J. Friedländer, has led to a reassessment of his importance. Through careful stylistic analysis, the identification of signed and dated works, and archival research, his oeuvre has been reconstructed and his contributions more fully appreciated.

Christus is now recognized as a crucial transitional figure. He absorbed the lessons of the first generation of Early Netherlandish masters and infused them with his own innovations, particularly in the systematic use of linear perspective and the development of a more intimate and psychologically nuanced approach to portraiture. His clear, ordered compositions and the quiet, contemplative mood of his paintings set him apart. He provided a vital link between the pioneering achievements of Van Eyck and the subsequent developments in Bruges painting, notably by Memling, and in Netherlandish art more broadly.

His influence extended to the depiction of interior spaces, creating believable settings that enhanced the narrative and emotional impact of his scenes. The clarity and precision of his technique, combined with his subtle handling of light and color, resulted in works of enduring beauty and quiet power. Petrus Christus may not have possessed the revolutionary genius of Van Eyck or the dramatic intensity of Van der Weyden, but his thoughtful innovations and refined artistry secure his place as a pivotal master of the Northern Renaissance, whose work continues to engage and fascinate viewers today. His legacy lies in his ability to synthesize tradition with innovation, creating a body of work that is both a product of its time and timeless in its appeal.