Antonello da Messina stands as a pivotal figure in the Italian Renaissance, a painter whose innovative techniques and unique artistic vision created a vital link between the artistic traditions of Northern Europe and Italy. His mastery of the oil medium, his profound psychological insight in portraiture, and his ability to synthesize diverse influences set him apart, leaving an indelible mark on the course of Western art, particularly on the Venetian school. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of this remarkable Sicilian artist.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Sicily

Antonello di Giovanni de Antonio, known to history as Antonello da Messina, was born in Messina, Sicily, around 1430. His father, Giovanni de Antonio, was a stonemason (mazonus), and his mother was possibly named Margherita. Sicily at this time was a cultural crossroads, part of the Kingdom of Naples under Aragonese rule, which fostered connections with Spain and, through it, with the Netherlands. This cosmopolitan environment likely provided Antonello with his first exposure to diverse artistic currents.

Details of his earliest training are scarce, but it is generally accepted that he received his initial artistic education in his hometown. Messina, a bustling port city, would have offered opportunities to see works from various regions. However, the most formative period of his early career began around 1450 when he traveled to Naples.

The Neapolitan Crucible: Influences and Apprenticeship

Naples, under King Alfonso V of Aragon, was a vibrant artistic center, attracting artists and artworks from across Europe. It was here that Antonello is documented to have apprenticed in the workshop of Niccolò Colantonio, a prominent painter in the city. Colantonio's own style was a fascinating amalgamation of influences, notably from Flemish and Provençal painting, which were highly prized at the Aragonese court.

In Colantonio's studio, Antonello would have encountered the meticulous realism, rich colors, and luminous effects characteristic of Early Netherlandish painters like Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden, whose works were known in Naples. The influence of Provençal artists, such as Enguerrand Quarton, with their strong sculptural forms and dramatic lighting, also played a role. This Neapolitan period was crucial for Antonello, as it exposed him to the oil painting techniques that were revolutionizing art in Northern Europe but were not yet widely practiced in Italy. He absorbed these influences, not merely imitating them, but beginning to synthesize them with Italianate sensibilities for monumental form and clear composition.

Return to Messina and Independent Practice

By 1457, Antonello had returned to Messina and established his own independent workshop. He was a recognized master, taking on apprentices, including his own son, Jacobello d'Antonio. During this period, he undertook various commissions, primarily religious works and portraits. While fewer works survive from this early Messinese phase, those that do, or are attributed to it, show a developing command of the oil medium and a growing individuality.

His reputation began to spread beyond Sicily. He is documented as having traveled for commissions, though the exact extent of these early travels is debated. What is clear is that he was refining his technique, particularly his ability to render textures, light, and human emotion with a new level of verisimilitude, largely thanks to his adept use of oil glazes.

The Enigma of Oil: Vasari's Tale and Technical Mastery

One of the most persistent legends surrounding Antonello, propagated by the 16th-century art historian Giorgio Vasari in his "Lives of the Artists," is that Antonello traveled to Flanders specifically to learn the secret of oil painting directly from Jan van Eyck. Vasari even concocted a detailed, albeit fictional, account of their meeting. While this narrative has been largely debunked by modern scholarship (Jan van Eyck died in 1441, when Antonello was still a child), it highlights the profound impact Antonello's oil technique had on his Italian contemporaries.

It is more likely that Antonello learned the rudiments of oil painting in Naples through Colantonio and by studying imported Flemish works. He then experimented and perfected the technique himself. Oil paint, with its slow drying time, allowed for greater blending, subtle gradations of tone, and the creation of deep, luminous colors through the application of multiple translucent layers (glazes) over a light ground. This was a significant departure from tempera, the dominant medium in Italy, which dried quickly and produced a more matte finish. Antonello's mastery of oil allowed him to achieve a previously unseen realism in Italian painting, particularly in the rendering of light, texture, and psychological presence.

Key Masterpieces and Stylistic Evolution

Antonello's oeuvre, though not vast, contains several masterpieces that illustrate his artistic development and unique contributions.

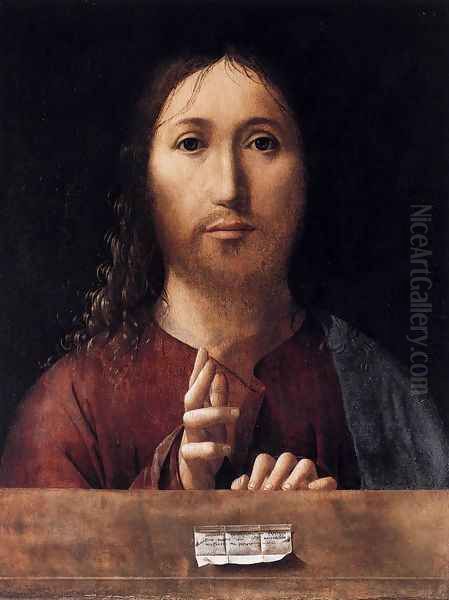

Salvator Mundi (c. 1465-1475)

One of his most iconic early works, the Salvator Mundi (now in the National Gallery, London), showcases his burgeoning skill. Christ is depicted frontally, blessing the viewer. The meticulous detail in the hair and beard, the subtle modeling of the face, and the intense, direct gaze demonstrate a clear Northern influence. Yet, the sculptural solidity of the form and the dignified composure also speak to an Italian sensibility. The painting is notable for its illusionistic rendering of Christ's hand, which appears to rest on a parapet, breaking the picture plane and engaging the viewer directly.

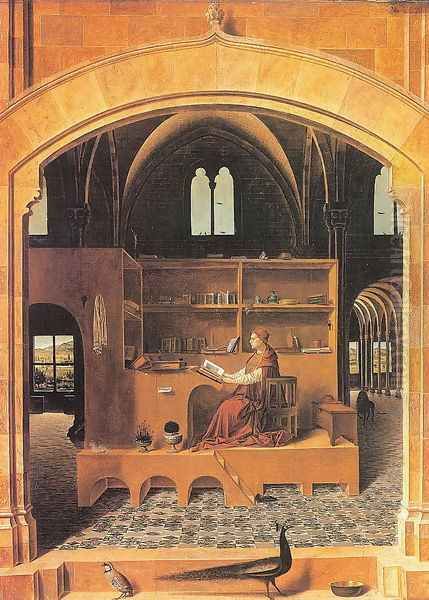

St. Jerome in His Study (c. 1474-1475)

Often considered one of his supreme achievements, St. Jerome in His Study (National Gallery, London) is a marvel of perspective, detail, and atmosphere. The saint is depicted in a vast, cathedral-like interior, absorbed in his reading. The complex architectural space is rendered with mathematical precision, reminiscent of Italian masters of perspective like Piero della Francesca. However, the wealth of meticulously observed details – the books, the tiles, the animals (lion, peacock, partridge), the distant landscape seen through windows – is distinctly Flemish. Antonello masterfully uses light, streaming in from multiple sources, to unify the composition and create a serene, scholarly ambiance. This work perfectly encapsulates his synthesis of Italian spatial construction and Northern European realism.

Annunciation (1474)

The Annunciation in Palermo (Galleria Regionale della Sicilia) is a work of profound psychological depth and compositional innovation. Unlike traditional depictions, Antonello focuses solely on the Virgin Mary at the moment she receives the angel's message (the angel Gabriel is not physically present, or is implied to be outside the frame). Her reaction is one of quiet contemplation and dignified acceptance. Her hand gesture, a subtle acknowledgment, is masterfully rendered. The lectern before her, with its open book, is a tour-de-force of still-life painting. The use of light and shadow creates a palpable sense of volume and intimacy. This painting highlights Antonello's ability to convey deep emotion through subtle means.

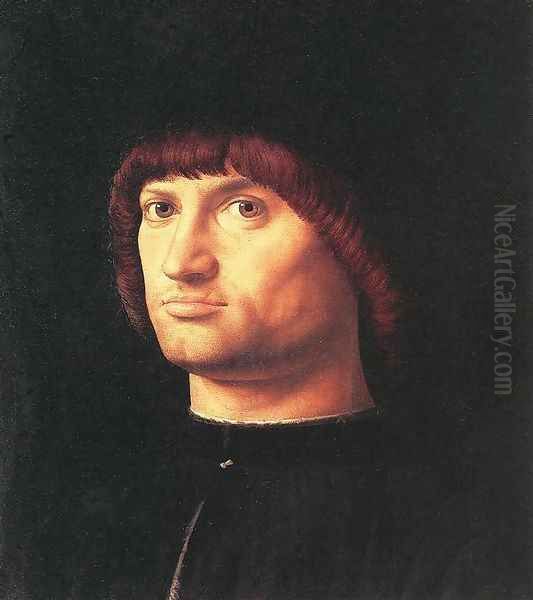

Portraiture: Capturing the Inner Life

Antonello was a revolutionary portraitist. His portraits, typically bust-length and often set against a dark, plain background, are characterized by their unflinching realism and psychological penetration. He abandoned the profile view common in earlier Italian portraiture in favor of the three-quarter view favored by Flemish artists, which allowed for a more nuanced depiction of character.

The Portrait of a Man (c. 1475-1476), sometimes identified as a "Condottiero" (Louvre, Paris), is a prime example. The sitter's direct, almost challenging gaze, the subtle scar on his upper lip, and the strong modeling of his features create an impression of a forceful personality. Antonello's portraits are not idealized; they capture the individuality of his subjects with remarkable acuity. Other notable portraits include those in the Museo Civico d'Arte Antica in Turin and the National Gallery, London. These works significantly influenced the development of portraiture in Venice and beyond.

The Venetian Sojourn (1475-1476) and its Profound Impact

Perhaps the most consequential period of Antonello's career was his stay in Venice from 1475 to 1476. Though brief, his presence and work had a transformative effect on Venetian painting. Venice, with its strong mercantile ties to Northern Europe, was already receptive to Netherlandish art, but Antonello's arrival, with his fully mastered oil technique and powerful style, acted as a catalyst.

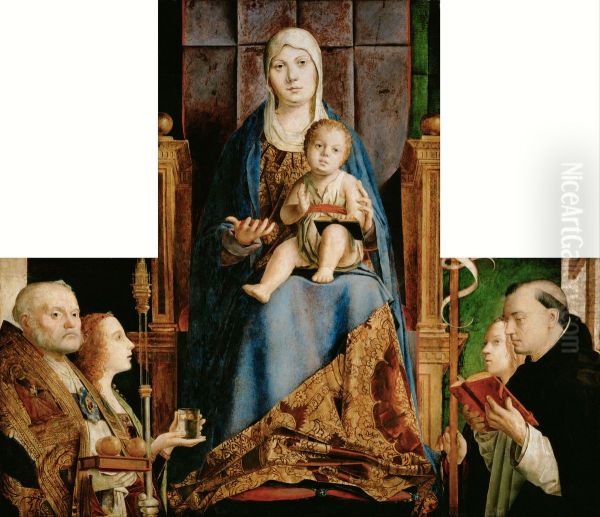

During his time in Venice, he painted the now-fragmented San Cassiano Altarpiece (1475-1476). Though only parts survive (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), its original composition, a sacra conversazione (sacred conversation) with figures arranged in a unified architectural space, was groundbreaking. It demonstrated a harmonious blend of Italianate monumental figures, perspectival depth, and the rich color and light effects of oil painting. This work deeply impressed Venetian artists.

Most significantly, Antonello came into contact with Giovanni Bellini, the leading painter in Venice at the time. The interaction between these two masters was mutually beneficial. Bellini, already a highly accomplished artist working primarily in tempera, was profoundly influenced by Antonello's oil technique, his use of atmospheric light, and his approach to portraiture. Bellini quickly adopted and adapted the oil medium, leading to the luminous, color-rich style that would define the Venetian School for generations. Artists like Alvise Vivarini, Gentile Bellini (Giovanni's brother), Vittore Carpaccio, and later Giorgione and Titian, all benefited from the technical and stylistic innovations that Antonello helped introduce and popularize in Venice.

Antonello's influence was not limited to technique. His emphasis on naturalism, psychological depth in portraiture, and the integration of figures within atmospheric landscapes resonated strongly with the Venetian artistic temperament.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Antonello's career unfolded within a rich tapestry of artistic activity. Beyond his teacher Niccolò Colantonio and his pivotal interaction with Giovanni Bellini, his work shows an awareness of, and dialogue with, other major figures.

The influence of Jan van Eyck and Petrus Christus (whom some scholars suggest Antonello might have met in Milan, though this is speculative) is undeniable in his oil technique and meticulous realism. While a direct meeting with Van Eyck is a myth, the circulation of their works was significant.

His understanding of perspective and monumental form suggests an awareness of Central Italian masters like Piero della Francesca. Though no direct contact is documented, the intellectual currents of the Renaissance, including treatises on perspective, were spreading. In Northern Italy, artists like Andrea Mantegna were also exploring rigorous perspective and classical forms, creating a parallel path of innovation.

In Venice, besides the Bellini brothers and Alvise Vivarini, other artists like Carlo Crivelli (though with a more Gothicizing, decorative style) were active. The generation following Antonello's Venetian visit, including Vittore Carpaccio, Cima da Conegliano, and the young Giorgione and Titian, would build upon the foundations he helped lay, particularly in the use of oil and the development of atmospheric painting.

His legacy was also carried on by his son, Jacobello d'Antonio, and his nephews, Antonio de Saliba, Pietro de Saliba, and Salvo d’Antonio. These family members continued to work in a style derived from Antonello, primarily in Sicily and Southern Italy, ensuring the dissemination of his artistic innovations in his native region. Other Sicilian painters, such as Giovanni di Italia and San Domenico Campagnola (though the latter is more associated with the Venetian mainland later), also show traces of his influence.

Controversies and Scholarly Debates

Antonello's life and work, like that of many Renaissance artists, are subject to scholarly debate and some historical uncertainties.

The Flanders Journey: As mentioned, Vasari's account of Antonello learning oil painting directly from Jan van Eyck in Flanders is now considered a romantic fabrication. The transmission of oil painting techniques was more complex and likely occurred through multiple channels.

Attribution Issues: The precise attribution of some works to Antonello, his workshop, or his followers (including family members like Jacobello or his nephews) remains a subject of discussion among art historians. The similarity in style, particularly for workshop productions, can make definitive attributions challenging. For example, the exact authorship of some versions of Ecce Homo or certain devotional panels has been debated.

Dating of Works: The precise dating of some of his paintings is also debated, relying on stylistic analysis and limited documentary evidence. This can affect our understanding of his artistic development and the timeline of his influences.

The "Introduction" of Oil Painting to Italy: While Antonello was a key figure in popularizing and mastering oil painting in Italy, particularly in Venice, he was not solely responsible for its "introduction." Oil-based binders were known and used sporadically by Italian artists before him. However, his sophisticated use of the Netherlandish glazing technique was revolutionary and had a far more significant impact than earlier, more isolated experiments.

Extent of Travels: While his presence in Naples and Venice is well-documented, the full extent of his travels, particularly to other Italian centers like Rome or Milan (where he might have encountered Petrus Christus), is less certain and often based on stylistic inferences rather than concrete proof.

These debates are part of the ongoing scholarly effort to reconstruct a more accurate and nuanced understanding of Antonello's career and his place in Renaissance art.

Final Years and Artistic Legacy

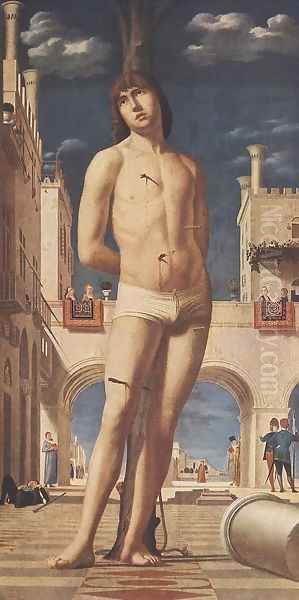

After his transformative stay in Venice, Antonello returned to Messina in the autumn of 1476. He continued to work, but his life was cut short. He died in Messina in February 1479, likely still in his forties. His will, dated that month, indicates he was still actively engaged in commissions. His son, Jacobello, completed some of his unfinished works, including, it is believed, the St. Sebastian (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden), a powerful depiction of the martyred saint set against a meticulously rendered cityscape, showcasing Antonello's mature command of anatomy, perspective, and atmospheric effects.

Antonello da Messina's legacy is profound. He was a crucial conduit for the transmission of Netherlandish oil painting techniques to Italy, fundamentally altering the trajectory of Italian art, especially in Venice. His synthesis of Northern European realism with Italianate monumentality and psychological depth created a unique and influential style.

His contributions include:

Mastery of Oil: He demonstrated the expressive potential of the oil medium, achieving unprecedented luminosity, rich color, and subtle modeling.

Revolutionary Portraiture: His psychologically acute portraits, employing the three-quarter view, set a new standard for realism and character depiction.

Influence on the Venetian School: His work was a direct catalyst for Giovanni Bellini's adoption of oil painting, which in turn shaped the entire Venetian Renaissance and its emphasis on color, light, and atmosphere.

Bridge Between North and South: He successfully fused the detailed naturalism of the North with the Italian tradition of harmonious composition and idealized form.

Antonello da Messina was more than just a technically proficient painter; he was an innovator who understood how to imbue his subjects with a palpable sense of presence and inner life. His ability to absorb diverse influences and forge them into a coherent and powerful personal style marks him as one of the most significant and forward-looking artists of the 15th century. His impact resonated through the High Renaissance and beyond, securing his place as a true master of European art.