Pieter Jansz. Pourbus (c. 1523/1524 – 30 January 1584) stands as a pivotal figure in the art of the Southern Netherlands during the 16th century. A painter, cartographer, surveyor, and engineer, Pourbus was a true Renaissance man whose multifaceted talents left an indelible mark on the city of Bruges, his adopted home. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries like Pieter Bruegel the Elder or later Flemish Baroque giants such as Peter Paul Rubens, Pourbus was a leading artist of his generation, skillfully navigating the transition from the late Gothic traditions of Early Netherlandish painting towards the burgeoning influences of the Italian Renaissance and the emerging Mannerist style. His prolific output, particularly in portraiture and religious subjects, provides a rich visual record of Bruges during a period of significant social, economic, and religious change.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Gouda, in the Northern Netherlands, around 1523 or 1524, relatively little is definitively known about Pieter Pourbus's earliest years or his initial artistic training there. It is presumed he received foundational instruction in Gouda, a town with its own artistic traditions, though the specifics remain elusive. The decisive move in his career came when he relocated to Bruges, likely in the early 1540s. Bruges, though past its absolute zenith as the economic powerhouse of Northern Europe, was still a significant cultural and artistic center, heir to the legacy of masters like Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling.

By 1543, Pourbus was registered as a master in the Bruges Guild of Saint Luke, the painters' guild. This formal recognition indicates he had completed his apprenticeship and was deemed proficient enough to operate independently. A crucial step in his establishment within the Bruges artistic community was his association with Lancelot Blondeel (1498–1561). Blondeel was a prominent and versatile artist in Bruges, known not only as a painter but also as an architect, designer of sculptures and stained glass, and a cartographer. Pourbus entered Blondeel’s workshop, and in 1545 or 1546, he married Blondeel’s daughter, Anna. This union was strategically important, as it cemented his ties to a leading local workshop and likely facilitated his integration into the city's artistic and social networks. He eventually inherited Blondeel's workshop, providing him with a solid base of operations.

His early works from this period would have absorbed the prevailing Bruges style, which still bore the hallmarks of the meticulous realism and rich symbolism of earlier Flemish masters. However, the winds of change were blowing from Italy, and artists across Northern Europe were increasingly engaging with the ideals of the Italian Renaissance – its emphasis on classical forms, anatomical accuracy, perspective, and dramatic composition. Pourbus was no exception, and his art would increasingly reflect this dialogue between local tradition and international innovation.

Rise to Prominence in Bruges

Pieter Pourbus quickly established himself as a leading painter in Bruges. His diligence, skill, and ability to adapt to the evolving tastes of his patrons ensured a steady stream of commissions. He became a respected citizen, actively participating in the civic and religious life of the city. He was a member of the crossbowmen’s guild of St. George, a prestigious civic guard company, which further elevated his social standing and connected him with potential patrons among the city's elite.

His reputation grew through a variety of commissions, including altarpieces for churches and chapels, devotional paintings for private individuals, and, significantly, portraits of Bruges' affluent citizenry – merchants, clerics, and civic officials. The demand for portraiture was high among the prosperous middle and upper classes, who wished to commemorate themselves and their families. Pourbus excelled in this genre, capturing not only a likeness but also conveying the status and character of his sitters.

Beyond painting, Pourbus's talents as a surveyor and cartographer were highly valued. Bruges, with its intricate network of canals and its surrounding polders (reclaimed land), required accurate maps for administration, defense, and water management. Pourbus's technical skills in these areas were exceptional, demonstrating a mathematical and scientific aptitude that complemented his artistic abilities. This versatility was characteristic of many Renaissance artists, who did not always see a strict division between art and science. Figures like Leonardo da Vinci epitomized this ideal, and while Pourbus operated on a different scale, his diverse skills reflect a similar intellectual breadth.

Religious Paintings: Tradition and Innovation

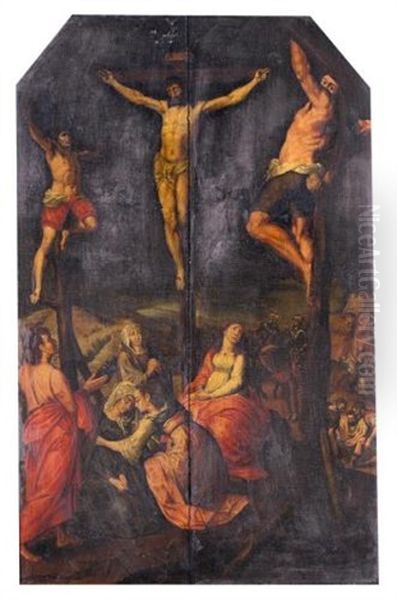

Religious subjects formed a substantial part of Pourbus's oeuvre, catering to the needs of churches, monasteries, and private patrons. His religious works demonstrate a careful balance between the established iconographic traditions of Netherlandish art and the newer stylistic currents emanating from Italy. He was adept at creating large-scale altarpieces with complex narratives and numerous figures, as well as smaller, more intimate devotional panels.

One of his most significant religious commissions is the Last Supper (1562), painted for the Church of Our Lady (Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk) in Bruges, now housed in St. Saviour's Cathedral, Bruges. This work showcases Pourbus's ability to organize a complex scene with clarity. While the theme was a standard one, Pourbus's treatment shows an awareness of Italian compositional solutions, possibly known through prints or the work of other Netherlandish artists who had traveled south, such as Jan van Scorel or Maerten van Heemskerck. The figures are rendered with a degreeel of monumentality, and there is a clear attempt at conveying psychological interaction among the apostles. The careful attention to detail in the still life elements on the table, however, remains firmly rooted in the Flemish tradition.

Another major work is The Last Judgment (1551), now in the Groeningemuseum, Bruges. Commissioned by the Franc of Bruges (the countryside surrounding the city, which had its own administration), this large and ambitious painting depicts the apocalyptic scene with dramatic intensity. Christ presides in judgment, flanked by saints and apostles, while below, the dead rise, the blessed are guided to heaven, and the damned are dragged to hell. Pourbus masterfully handles the multitude of figures and the complex spatial arrangement. The depiction of the nudes, while perhaps not displaying the idealized anatomical perfection of Italian masters like Michelangelo, shows a confident grasp of human form and movement. The work served as a powerful reminder of divine justice and was a common subject for town halls and courts of justice.

Other notable religious works include the Van Belle Triptych (1556), also in St. Saviour's Cathedral, which depicts the Presentation of Mary in the Temple, the Marriage of the Virgin, and the Annunciation. His Adoration of the Shepherds and various depictions of the Crucifixion and Passion of Christ further illustrate his contribution to religious art in Bruges. These works often feature rich colors, detailed rendering of textures, and expressive figures, though generally avoiding the extreme contortions or emotionalism of High Mannerism as seen in the works of, for example, Rosso Fiorentino or Pontormo in Italy. Pourbus’s style remained more restrained, a kind of "Flemish Mannerism" that was tempered by local sensibilities. He was certainly aware of the work of Antwerp Mannerists and artists like Frans Floris, who was a key figure in introducing Italianate styles to the Netherlands.

Master of Portraiture

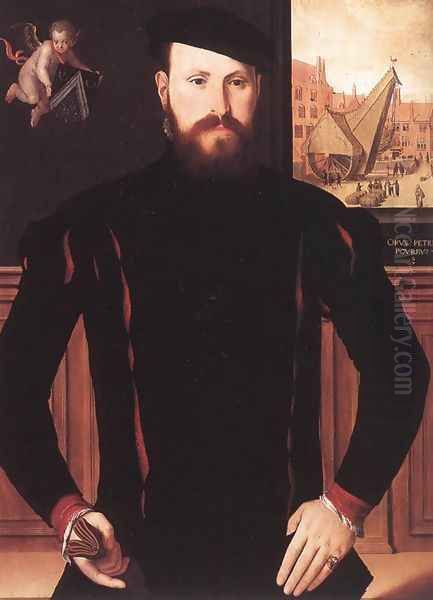

Pieter Pourbus was arguably at his most consistently brilliant in the field of portraiture. He developed a distinctive style that combined the meticulous realism of the Netherlandish tradition with a sense of dignity and psychological presence. His portraits are invaluable historical documents, offering insights into the appearance, attire, and social standing of the Bruges elite in the mid-16th century.

His sitters are typically presented with a sober, direct gaze, often against a plain dark background, which focuses attention entirely on the individual. He paid exquisite attention to the rendering of fabrics – silks, velvets, furs – and jewelry, all indicators of wealth and status. Hands are often prominently featured and carefully rendered, sometimes holding an object symbolic of the sitter's profession or piety, such as a prayer book, gloves, or a skull (as a memento mori).

Among his most celebrated portraits are those of Jan van Eyewerve and Jacquemyne Buuck (1551, Groeningemuseum, Bruges). These pendant portraits depict a husband and wife, a common format. Jan van Eyewerve was a prominent Bruges citizen and tax collector. Pourbus captures him with an air of serious responsibility, his fur-lined robe and gold chain denoting his office. Jacquemyne Buuck is portrayed with equal gravity, her piety suggested by the prayer book she holds. The detailed depiction of her headdress and jewelry is characteristic of Pourbus's skill.

He also painted group portraits, such as the Members of the Noble Brotherhood of the Holy Blood (1556, Museum of the Holy Blood, Bruges), which, although damaged, shows his ability to manage multiple figures within a cohesive composition. His portraits of the Ghuyse-van der Muelen couple (c. 1550-1554, Groeningemuseum) are another fine example of his sensitive portrayal of married couples.

Pourbus's portrait style can be seen as a continuation of the legacy of earlier Bruges masters like Hans Memling, but with an updated sensibility. While Memling's portraits often have a serene, almost iconic quality, Pourbus's sitters, while dignified, often feel more individualized and psychologically present. He avoids excessive flattery, presenting his subjects with a degree of objective realism. His approach contrasts with the more flamboyant or idealized portraiture developing in some Italian centers, or the more courtly style that would later be perfected by artists like his own grandson, Frans Pourbus the Younger, or Anthony van Dyck.

Cartography and Engineering: The Scientific Mind

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Pieter Pourbus was a highly accomplished cartographer and surveyor. This aspect of his career underscores his intellectual versatility and his practical skills. In an era when accurate maps were of immense strategic and economic importance, Pourbus's contributions were highly valued.

His most famous cartographic achievement is the Great Map of the Liberty of Bruges (1561-1571). This was a monumental undertaking, a detailed planimetric map of Bruges and the surrounding district, the Franc of Bruges. The map, painted on canvas, was remarkable for its accuracy, achieved through meticulous surveying techniques. It depicted not only the topography, roads, and waterways but also individual buildings, abbeys, and castles, providing an invaluable historical record of the region in the 16th century. The original map is now in the Groeningemuseum. The precision and detail of this map demonstrate Pourbus's mastery of geometry and measurement, skills that also informed the perspectival construction in his paintings.

He was also involved in other surveying projects and possibly some hydraulic engineering work, given Bruges's reliance on its water systems. In 1561, he was commissioned to create a plan for the city's fortifications, although this project was not fully realized. His technical drawings and plans were as meticulously executed as his paintings, showcasing a mind that could seamlessly integrate artistic sensibility with scientific rigor. This dual expertise was not uncommon; for instance, Albrecht Dürer in Germany also wrote treatises on geometry and fortification. Pourbus's work in this field places him in the company of other artist-engineers of the Renaissance.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Techniques

Pieter Pourbus's artistic style is a fascinating amalgamation of native Netherlandish traditions and the burgeoning influence of the Italian Renaissance, particularly its Mannerist phase. He inherited the meticulous attention to detail, the rich oil glazing techniques, and the often somber piety of the Early Netherlandish school, exemplified by artists like Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Hans Memling.

However, by the mid-16th century, the artistic landscape was changing. The innovations of Italian artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo, and later Mannerists like Bronzino, Pontormo, and Parmigianino, were becoming known in the North through prints, travel, and the work of Netherlandish artists who had studied in Italy (the "Romanists"). Pourbus, while he is not documented as having traveled to Italy himself, was clearly aware of these developments. His figures often show a greater sense of volume and anatomical understanding than those of earlier Flemish painters. His compositions, particularly in larger narrative scenes, can exhibit a more dynamic and complex arrangement, characteristic of Mannerist tendencies.

His use of color was typically rich and harmonious, with a preference for strong, clear hues. He was a master of the oil glazing technique, building up layers of translucent paint to achieve depth, luminosity, and subtle gradations of tone. Infrared reflectography studies of his paintings have revealed detailed underdrawings, often executed with a brush. These underdrawings show that he planned his compositions carefully, sometimes using a grid system for transferring designs, a technique also employed by contemporaries like Cornelis Engebrechtsz.

In his religious works, Pourbus often borrowed compositional motifs from other artists, a common practice at the time. For instance, his Last Supper shows awareness of compositions by artists like Pieter Coecke van Aelst, who himself had helped disseminate Italian Renaissance forms in the Netherlands. However, Pourbus always adapted these borrowings to his own distinct style, often imbuing them with a particular Flemish sobriety and emotional restraint.

His portraits, while adhering to conventions of the genre, show a keen observational skill and an ability to convey the sitter's personality. The clarity of form, the precise rendering of textures, and the often direct, unflinching gaze of his subjects are hallmarks of his portraiture. He was less interested in the overt displays of virtuosity or the elongated, elegant figures typical of some Italian Mannerist portraitists like Bronzino, preferring a more grounded and realistic representation.

The Pourbus Dynasty and Artistic Legacy

Pieter Pourbus was the progenitor of an artistic dynasty that continued for several generations. His son, Frans Pourbus the Elder (1545–1581), also became a painter, training initially with his father before reportedly studying with Frans Floris in Antwerp. Frans the Elder was a talented artist in his own right, known for his religious scenes and portraits, though his career was cut short by an early death.

The family's artistic legacy was most prominently carried on by Pieter's grandson, Frans Pourbus the Younger (1569–1622). Frans the Younger achieved international fame as a court portraitist, working for prominent patrons across Europe, including the Gonzaga family in Mantua (where Peter Paul Rubens also worked for a time) and the courts of Brussels, Paris (for Marie de' Medici), and Madrid. His style was more aligned with the emerging international Baroque court portraiture, characterized by elegance, refinement, and a sophisticated rendering of status.

Pieter Pourbus's direct influence was most strongly felt in Bruges, where he was the dominant painter for several decades. He trained a number of pupils in his workshop, though none achieved his level of prominence. His impact on the broader Netherlandish art scene was perhaps more subtle than that of his Antwerp contemporaries like Frans Floris or Pieter Aertsen. However, his consistent quality, his professionalism, and his ability to synthesize tradition and innovation made him a key figure in the Flemish Renaissance.

His work represents an important bridge between the late Gothic style of the 15th-century Bruges school and the more Italianate and Mannerist trends of the 16th century. He maintained a high level of craftsmanship at a time when Bruges was experiencing economic decline relative to Antwerp, which had become the new commercial and artistic hub of the Southern Netherlands. Despite this shift, Pourbus ensured that Bruges remained a center of artistic production.

The religious upheavals of the 16th century, particularly the waves of Iconoclasm (Beeldenstorm) that swept through the Netherlands in 1566 and later, had a profound impact on the artistic landscape. Many existing artworks were destroyed, and the demand for new religious art fluctuated with the changing religious climate. Pourbus navigated these turbulent times, continuing to receive commissions from both Catholic patrons and, at times, the Calvinist city government when it held power in Bruges. His ability to adapt suggests a pragmatic approach to his career.

Connections to Contemporaries and Later Masters

While Pourbus was primarily based in Bruges, the art world of the 16th-century Netherlands was interconnected. Artists traveled, prints circulated widely, and stylistic influences crossed regional boundaries. Pourbus would have been aware of the leading figures in Antwerp, such as Frans Floris, Pieter Aertsen, Joachim Beuckelaer, and the early works of the Bruegel dynasty (Pieter Bruegel the Elder). While his style remained distinct from the often more dynamic and earthy genre scenes of Aertsen or the peasant scenes of Bruegel, there was a shared cultural context.

His relationship with Lancelot Blondeel was foundational. He also had professional interactions with other Bruges artists and craftsmen. The influence of Italian art, as mentioned, was significant, though likely filtered through prints and the work of "Romanist" Netherlandish painters rather than direct experience. Artists like Jan Gossaert (Mabuse) and Bernard van Orley had earlier played a role in introducing Italian Renaissance elements to the North.

Comparisons with later masters like Peter Paul Rubens are complex. Rubens, active several decades after Pourbus's death, represented the full flowering of the Flemish Baroque, a style far more dynamic, dramatic, and overtly emotional than Pourbus's more restrained Renaissance-Mannerist idiom. However, Pourbus, through his son Frans the Elder and grandson Frans the Younger, contributed to the artistic lineage from which the Baroque era emerged. Frans Pourbus the Younger was a contemporary of the young Rubens, and both worked for the Gonzaga court in Mantua, though their styles differed.

There is no direct documented artistic interaction between Pieter Pourbus and Jan Brueghel the Elder. Jan Brueghel, known for his detailed landscapes and flower paintings, was part of a different artistic circle, primarily in Antwerp and Brussels, and often collaborated with Rubens. Their artistic concerns and specializations were quite distinct from Pourbus's primary focus on religious narratives and portraiture in Bruges.

The misattribution of Pourbus's works to other artists, such as Adriaen Thomasz. Key or even lesser-known figures, occurred in later centuries, highlighting periods when his distinct artistic personality was less understood or appreciated. Modern scholarship has done much to re-establish his oeuvre and his rightful place in the history of Netherlandish art.

Conclusion: A Versatile Renaissance Figure

Pieter Pourbus died in Bruges on 30 January 1584. He was buried in the Church of Our Lady. His death marked the end of a long and productive career that significantly shaped the artistic landscape of Bruges in the 16th century. He was more than just a painter; his work as a cartographer and surveyor demonstrates a scientific acumen that complemented his artistic talents, embodying the Renaissance ideal of the versatile individual.

His paintings, characterized by their clarity, meticulous execution, and dignified portrayal of human subjects, provide a vital link between the rich traditions of Early Netherlandish art and the evolving styles of the later Renaissance and early Mannerism. In his religious works, he skillfully blended traditional iconography with new compositional ideas, while his portraits offer a compelling gallery of the citizens who shaped Bruges in his time. His maps, particularly the Great Map of the Liberty of Bruges, remain extraordinary testaments to his technical skill and historical importance.

Though Bruges's golden age was waning, Pieter Pourbus maintained a high standard of artistic production, ensuring the city's continued relevance in the cultural sphere. He successfully navigated a period of profound religious and social change, leaving behind a substantial body of work that continues to be studied and admired for its artistic quality and historical significance. As a master painter, skilled cartographer, and founder of an artistic dynasty, Pieter Pourbus holds a distinguished and enduring place in the annals of Flemish art.