Philipp Franck (1860-1944) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of German art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter, graphic artist, and influential educator, Franck navigated the transition from 19th-century academic traditions to the burgeoning modernism of the new era. His life and work are intrinsically linked with the development of German Impressionism and the pivotal Berlin Secession movement, as well as significant reforms in art education. Born in Frankfurt am Main, his journey took him through key artistic centers, culminating in a long and productive career primarily based in Berlin, where his luminous depictions of the Wannsee region became iconic.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations in Frankfurt

Philipp Franck was born on April 9, 1860, in Frankfurt am Main. His early life was marked by a common narrative for many aspiring artists of the time: a parental vision for a more conventional career path clashing with an undeniable passion for the arts. Franck's father had initially hoped his son would pursue architecture, a profession perceived as more stable and respectable. However, the young Philipp was irresistibly drawn to painting and drawing, demonstrating a precocious talent that would ultimately define his life's work.

To nurture this burgeoning interest, Franck enrolled at the prestigious Städelisches Kunstinstitut in Frankfurt, one of Germany's oldest and most renowned art schools. There, he received his foundational artistic training under the tutelage of respected masters such as Heinrich Hasselhorst (1825-1904), known for his genre scenes and historical paintings, and Eduard Jakob von Steinle (1810-1886), a prominent figure associated with the late Nazarene movement, celebrated for his religious and historical compositions. This early exposure to different artistic approaches provided Franck with a solid technical grounding, even as he began to seek his own distinct voice.

Formative Years: Kronberg and the Düsseldorf Influence

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons and immerse himself more directly in contemporary practices, Philipp Franck made a significant move in 1879. He traveled to Kronberg im Taunus, a small town near Frankfurt that had become a magnet for artists, forming the Kronberg Artists' Colony. This colony was a place where painters sought to escape the confines of academic studios and engage more directly with nature, a precursor to the plein air painting ethos that would later define Impressionism.

In Kronberg, Franck came under the mentorship of Anton Burger (1824-1905), a leading figure of the colony and a respected landscape and genre painter. Burger, who had himself studied in Frankfurt and Munich, was known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his commitment to capturing the local atmosphere. For three years, Franck studied closely with Burger, absorbing his approach to landscape painting and the importance of direct observation. This period was crucial in shaping Franck's affinity for nature and his developing skills in rendering light and atmosphere. Other artists associated with the Kronberg colony, such as Jakob Fürchtegott Dielmann (1809-1885), also contributed to the vibrant artistic environment that nurtured young talents like Franck.

Following his formative time in Kronberg, Franck continued his artistic education by enrolling at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Art Academy). The Düsseldorf School was internationally renowned in the 19th century, particularly for its detailed and often narrative landscape and genre paintings, with artists like Andreas Achenbach (1815-1910) and Oswald Achenbach (1827-1905) having established its reputation. While Franck absorbed the technical proficiency emphasized there, his artistic inclinations were already steering him towards a more modern, light-infused aesthetic.

Berlin: The Epicenter of Artistic Innovation

The late 19th century saw Berlin rapidly ascending as Germany's political, economic, and cultural capital. It was a city buzzing with intellectual ferment and artistic experimentation, attracting ambitious talents from across the German-speaking world and beyond. Philipp Franck, like many of his contemporaries, was drawn to this dynamic environment. He eventually moved to Berlin, which would become his primary base for the remainder of his life and career.

In Berlin, Franck established himself as a painter and graphic artist. He found particular inspiration in the landscapes surrounding the city, especially the idyllic Wannsee lake district to the southwest. This area, with its expansive waters, wooded shorelines, and vibrant recreational life, provided him with an endless source of subject matter. His paintings of the Wannsee, often featuring his own family members enjoying leisure activities, became hallmarks of his oeuvre, characterized by their bright palettes, broken brushwork, and keen observation of light effects – all characteristic of the Impressionist style he increasingly embraced.

His decision to settle near Wannsee was not merely practical but deeply artistic. The changing seasons, the play of light on the water, and the human interaction with this natural setting offered a perfect outdoor studio. These works resonated with the growing urban bourgeoisie's appreciation for nature and leisure, themes also explored by his French Impressionist predecessors like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919).

Artistic Style: Embracing German Impressionism

Philipp Franck's artistic style evolved significantly from his early academic training. While he retained a strong foundation in drawing and composition, his mature work is firmly rooted in German Impressionism. This movement, while drawing inspiration from its French counterpart, developed its own distinct characteristics, often with a more somber palette or a greater emphasis on underlying structure and psychological depth, particularly in the works of artists like Max Liebermann (1847-1935), Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), and Max Slevogt (1868-1932).

Franck's Impressionism was characterized by a vibrant engagement with light and color. He excelled at capturing the fleeting moments of daily life and the atmospheric conditions of the landscapes he loved. His brushwork became looser and more expressive, allowing him to convey the immediacy of his visual experience. Unlike some of the more radical avant-garde movements that followed, Franck's Impressionism remained committed to representation, but it was a representation transformed by a subjective perception of reality, filtered through the artist's eye and sensibility.

His subjects were diverse, ranging from pure landscapes of the Wannsee and its environs to intimate family scenes, portraits, and depictions of everyday life. Works such as "Bathing Boys at the Wannsee," "Family in the Wannsee Garden," or "View of the Wannsee" exemplify his ability to combine genre elements with a profound appreciation for the natural setting. He often depicted his own children playing, boating, or simply enjoying the outdoors, infusing these scenes with a sense of warmth and personal connection. His palette, particularly in his Wannsee paintings, often featured bright blues, greens, and yellows, capturing the sun-drenched atmosphere of summer days.

Key Works and Thematic Focus

While it is challenging to pinpoint a single "most famous" work for Philipp Franck, his collective body of Wannsee paintings constitutes his most significant and recognizable contribution. These works are not just picturesque views but are imbued with a sense of lived experience. For instance, "Am Grossen Wannsee" (At the Great Wannsee) or "Segelboote auf dem Wannsee" (Sailboats on the Wannsee) capture the leisure and beauty of this popular Berlin retreat. His depictions often include figures, seamlessly integrated into the landscape, suggesting a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature.

Earlier in his career, he also engaged with genre scenes reflecting his training, such as the painting mentioned in some sources, "Donat, Merchie Bauern bei der Heuernte" (Donat and Merchie Peasants at the Hay Harvest). While the exact dating of such a work needs careful consideration relative to his birth year, it would point to an interest in rural labor, a common theme in 19th-century realism, before his full immersion into Impressionistic light and leisure scenes.

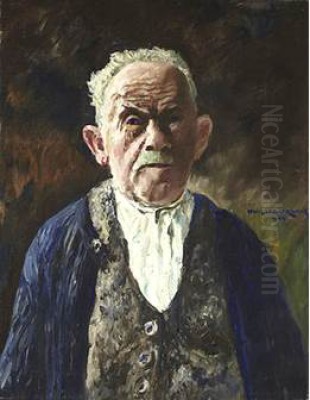

His portraiture, though perhaps less central than his landscapes, also demonstrates his skill. A notable example is his "Self-Portrait," which offers insight into the artist's persona. Throughout his career, Franck consistently explored the interplay of light, color, and atmosphere, whether in a sun-dappled forest path, a breezy lakeside scene, or the quiet intimacy of a domestic interior. His graphic works, including etchings and lithographs, further showcase his versatility and mastery of different media.

Franck the Educator: Reforming Art Pedagogy

Beyond his achievements as a painter, Philipp Franck made a profound and lasting impact as an art educator. He was deeply involved in the "Kunsterziehungsbewegung" (Art Education Movement), a significant reform initiative in Germany around the turn of the 20th century. This movement sought to move away from rote academic methods of teaching art, which often emphasized copying old masters, towards approaches that fostered creativity, individual expression, and a deeper appreciation for art among the general populace.

Franck's most significant role in this domain was his long tenure at the Königliche Kunstschule zu Berlin (Royal Art School of Berlin). This institution was primarily responsible for training art teachers for Prussian schools. Franck joined its faculty and eventually, from 1915, served as its director for many years, succeeding Martin Körte. Under his leadership, the school became a center for progressive art education. He championed reforms that emphasized direct observation, practical skills, and an understanding of modern artistic developments.

His influence extended to the curriculum and teaching methodologies, aiming to equip future art teachers with the tools to inspire creativity in their students rather than merely imparting technical rules. This commitment to art education reform was a vital part of his legacy, impacting generations of students and teachers and contributing to a broader modernization of art pedagogy in Germany. His work in this field paralleled efforts by other reformers across Europe who believed in the transformative power of art in education and society.

The Berlin Secession: A Voice for Modernity

Philipp Franck was a key figure in one of the most important institutional developments in German modern art: the Berlin Secession. Founded in 1898, the Berlin Secession was an artists' association that broke away from the established, conservative art institutions, particularly the Association of Berlin Artists and the state-run annual Great Berlin Art Exhibition, which were perceived as hostile to new artistic trends.

The Secession, under the leadership of its first president, Max Liebermann, provided a crucial platform for Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Symbolist artists to exhibit their work. Philipp Franck was not only a founding member but also served on its board for many years, playing an active role in its organization and exhibitions. This placed him at the heart of the modernist movement in Berlin, alongside other prominent members such as Walter Leistikow (1865-1908), who was a driving force behind its formation, Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), Lesser Ury (1861-1931), and George Mosson (1851-1933). Even international artists like Edvard Munch (1863-1944) exhibited with the Secession, highlighting its progressive stance.

Franck's involvement with the Berlin Secession underscored his commitment to artistic freedom and his alignment with the modern currents of his time. The Secession's exhibitions were vital for introducing the Berlin public to new forms of artistic expression and challenging the academic status quo. His participation solidified his position as a leading German Impressionist and an advocate for contemporary art.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Philipp Franck's career unfolded within a rich and complex artistic milieu. His teachers, Heinrich Hasselhorst and Eduard von Steinle, connected him to 19th-century academic traditions. His mentor Anton Burger linked him to the plein air practices of artists' colonies. In Düsseldorf, he would have been aware of the legacy of painters like Andreas and Oswald Achenbach.

In Berlin, he was part of a vibrant generation of artists. His colleagues in the Berlin Secession – Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, Walter Leistikow, and Käthe Kollwitz – were central to the German art scene. Liebermann, in particular, with his own famous villa and gardens at Wannsee, shared Franck's love for the region and a similar Impressionistic approach, though Liebermann often achieved greater international fame. Lesser Ury was another Berlin Impressionist known for his cityscapes and café scenes, while artists like Heinrich Zille (1858-1929) focused on the social realities of Berlin's working class.

The broader European context included the towering figures of French Impressionism – Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Degas – whose innovations had a profound, if sometimes delayed, impact on German art. While Franck developed his own distinct "German" Impressionist style, the underlying principles of capturing light and momentary effects were shared. He was also contemporary with Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), whose work would pave the way for even more radical movements in the early 20th century.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Philipp Franck continued to paint and teach into his later years. He remained dedicated to his Impressionistic style, capturing the beauty of the Wannsee and other subjects with undiminished passion. He lived through a period of immense social and political upheaval in Germany, including World War I, the Weimar Republic, and the rise of National Socialism. The cultural climate shifted dramatically, with new avant-garde movements like Expressionism, Dada, and New Objectivity challenging the tenets of Impressionism.

Despite these changes, Franck's commitment to his artistic vision remained steadfast. He passed away on March 13, 1944, in Berlin, during the tumultuous final years of World War II.

Philipp Franck's legacy is twofold. As a painter, he contributed significantly to the development and popularization of German Impressionism. His luminous and evocative depictions of the Wannsee region are cherished for their beauty and their ability to capture a specific sense of time and place. While perhaps not as widely known internationally as Liebermann, Corinth, or Slevogt, his work holds an important place in the narrative of German art at the turn of the century.

As an educator, his impact was arguably even more profound and far-reaching. His decades of work at the Königliche Kunstschule zu Berlin and his role in the Kunsterziehungsbewegung helped to modernize art education in Germany, fostering a more creative and less dogmatic approach to teaching. He influenced countless art teachers who, in turn, shaped the artistic sensibilities of subsequent generations.

Today, Philipp Franck's paintings are held in various public and private collections, primarily in Germany. Exhibitions of his work continue to draw appreciation for his skill, his sensitivity to light and color, and his contribution to the rich tapestry of German Impressionism. He remains a testament to an artist who successfully bridged the worlds of personal artistic creation and dedicated public service through education.

Conclusion: An Artist of Light and Learning

Philipp Franck was more than just a painter of pleasant landscapes; he was an artist deeply engaged with the currents of his time, a dedicated educator who sought to share the transformative power of art, and a key participant in the institutional shifts that defined German modernism. His canvases, particularly those inspired by the Wannsee, radiate a gentle luminosity and a profound affection for his subject matter, offering a window into the leisurely pursuits and natural beauty of early 20th-century Berlin. Simultaneously, his tireless efforts in art education reform left an indelible mark on how art was taught and perceived in Germany. While the clamor of more radical avant-garde movements may have sometimes overshadowed the quieter achievements of German Impressionists like Franck, his contribution to both the art and the pedagogy of his era remains significant and worthy of continued recognition and study. He stands as a distinguished representative of a generation that navigated the exciting and challenging transition into artistic modernity.