Curt Herrmann (1854–1929) stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of German art at the turn of the 20th century. A painter, educator, and an active participant in the progressive art movements of his time, Herrmann's journey from academic portraiture to becoming a fervent advocate and practitioner of Neo-Impressionism in Germany charts a fascinating course through a period of profound artistic transformation. His work, characterized by a sensitive engagement with light and colour, and his role in fostering avant-garde tendencies, particularly through the Berlin Secession, mark him as a pivotal artist who helped shape the course of modern art in his homeland.

Early Life and Academic Foundations

Born on February 1, 1854, in Merseburg, a town in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany, Curt Herrmann's early artistic inclinations led him away from a traditional university path. Instead, he chose to immerse himself directly in artistic training. His formal education began in the studio of Carl Steffeck, a notable history and animal painter in Berlin. This initial apprenticeship provided him with a solid grounding in traditional techniques. Subsequently, Herrmann sought to further refine his skills at the prestigious Munich Academy of Fine Arts, a leading institution in the German-speaking world, known for its emphasis on realism and a certain dark, tonal palette often referred to as the "Munich School."

During his formative years in Munich, Herrmann would have been exposed to an environment rich with artistic debate and diverse influences. The academy, while traditional, was also a place where artists grappled with emerging trends. Figures like Wilhelm Leibl, known for his powerful realism, and Franz von Stuck, who would later become a prominent Symbolist and co-founder of the Munich Secession, were active in the city, contributing to a dynamic artistic milieu. Herrmann's early work, as was common for academically trained artists of the period, focused on portraiture. He established himself as a freelance portrait painter, a genre that demanded technical skill and the ability to capture both likeness and character.

Transition and the Embrace of New Artistic Currents

Returning to Berlin, Herrmann continued his career, and notably, in 1893, he established a "Painting and Drawing School for Ladies." This initiative was significant, as opportunities for formal art education for women were still limited. He ran this school until 1903, demonstrating a commitment to art education and providing a space for aspiring female artists. During this period, his own artistic style began to evolve. Initially, like many artists of his generation across Europe, Herrmann was captivated by Japonisme – the influence of Japanese art, particularly Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which offered new perspectives on composition, colour, and subject matter.

The most decisive shift in Herrmann's artistic trajectory, however, came through his personal connections and his openness to the radical innovations emanating from France. Around 1896-1897, a pivotal encounter occurred, largely facilitated by his wife, Sophie Henriette Herrmann (née van de Velde, though her exact relation to Henry van de Velde is sometimes debated, the connection to his circle is clear), or through his burgeoning friendship with the Belgian architect and designer Henry van de Velde himself. Van de Velde was a key proponent of Art Nouveau (Jugendstil in Germany) and had strong ties to the French avant-garde. Through this network, Herrmann was introduced to the principles of Neo-Impressionism.

He forged lasting friendships with leading French Neo-Impressionists, including Paul Signac, who, after Georges Seurat's early death, became the chief theorist and promoter of the movement. He also connected with Henri-Edmond Cross and Maximilien Luce, both significant figures in the development of Pointillism or Divisionism. This technique involved applying small, distinct dots or strokes of pure colour to the canvas, relying on the viewer's eye to optically blend them, thereby achieving greater luminosity and vibrancy than traditional colour mixing. Herrmann was not just intellectually convinced by their theories of light and colour; he became an avid collector of their works, playing a crucial role in introducing and popularizing Neo-Impressionism within Berlin's art circles.

Pioneer of German Neo-Impressionism

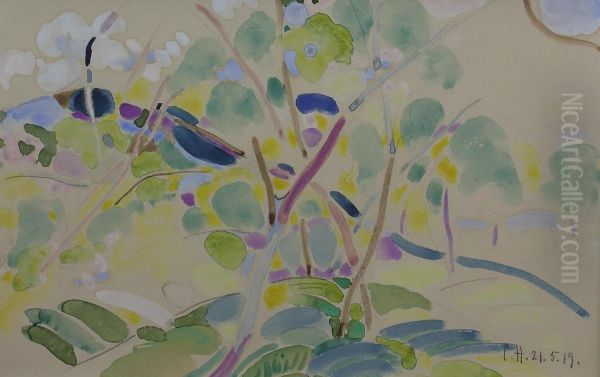

Inspired by his French contemporaries, Curt Herrmann wholeheartedly adopted the Neo-Impressionist technique. His canvases began to shimmer with meticulously applied dabs of colour, exploring the effects of light on landscapes, gardens, and floral subjects. This was a bold move in the relatively conservative German art scene, which was still largely dominated by academic realism and a more sombre Impressionism as championed by artists like Max Liebermann. Herrmann's work stood out for its scientific approach to colour and its pursuit of heightened optical sensation.

His garden scenes, such as "Blühender Garten" (Blooming Garden) or "Dame im Garten" (Lady in the Garden), became characteristic of his Neo-Impressionist phase. These paintings are often suffused with the bright, clear light of sunny days, with flowers and foliage rendered in a mosaic of vibrant hues. He applied the technique not only to landscapes but also to portraits and still lifes, consistently exploring the way light interacts with form and surface. His self-portraits from this period also reflect this stylistic commitment, showing a thoughtful artist engaged with the modern currents of his time.

Herrmann's dedication to Neo-Impressionism was not merely a stylistic affectation; it was rooted in a deep understanding of its theoretical underpinnings. He sought to capture the fleeting moments of nature, the play of sunlight, and the atmosphere of a place through a systematic application of colour. This made him one of the earliest and most important German exponents of the style, bridging the gap between French avant-garde developments and the evolving German art landscape.

The Berlin Secession and Artistic Activism

Curt Herrmann was not content to pursue his artistic vision in isolation. He was deeply involved in the organizational efforts to modernize the German art world. In 1898, he became one of the founding members of the Berlin Secession. This influential group, initially led by Max Liebermann, included prominent artists such as Walter Leistikow, Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, and Käthe Kollwitz. The Secession was formed in protest against the conservative policies of the official Association of Berlin Artists and the academic Salon, which frequently rejected more progressive artworks.

The Berlin Secession provided a crucial platform for modern art in Germany, organizing independent exhibitions that showcased a wide range of styles, from German Impressionism to Symbolism and, thanks to members like Herrmann, Neo-Impressionism. Herrmann's participation was vital; he not only exhibited his own Neo-Impressionist works but also used his influence to promote the art of his French colleagues. His collection of works by Signac, Cross, and Luce was often drawn upon for exhibitions, educating the Berlin public and fellow artists about these new international trends.

His commitment to artistic reform continued with his involvement in the founding of the "Deutscher Künstlerbund" (Association of German Artists) in 1903, under the initiative of Count Harry Kessler, a significant patron of modern art. This national organization aimed to protect the interests of artists and promote artistic freedom across Germany, further challenging the dominance of state-controlled art institutions. Herrmann's role in these organizations underscores his belief in the importance of artists taking control of their own representation and fostering a climate conducive to innovation.

The Freie Secession and Later Years

The Berlin Secession, despite its initial success, eventually experienced its own internal tensions. Disagreements over exhibition policies and the direction of modern art led to a split. In 1914, on the eve of World War I, a group of artists, including Max Liebermann (who had resigned from the Berlin Secession presidency in 1911), Ernst Barlach, Max Beckmann, and Curt Herrmann himself, formed the "Freie Secession" (Free Secession). Herrmann played a leading role in this new group, serving as its president during the challenging years of the First World War.

The Freie Secession aimed to be even more inclusive and open to the latest avant-garde developments, including Expressionism, which was then gaining momentum. Herrmann's leadership during this period highlights his enduring commitment to artistic pluralism and his support for younger generations of artists pushing boundaries.

Throughout his career, Herrmann maintained a close friendship with Henry van de Velde. This relationship was mutually enriching, with van de Velde's theories on design and applied arts likely influencing Herrmann's interest in decorative painting and the overall aesthetic harmony of his compositions. Van de Velde, in turn, benefited from Herrmann's connections within the Berlin art world. Their shared interest in progressive art and design created a strong bond that lasted for many years.

One notable work from his later period is "Flamingo" (1917). While the specific context of this painting might require deeper iconographical analysis, its creation during the war years could imbue it with symbolic meaning, perhaps reflecting on beauty and fragility in a world consumed by conflict, or as suggested by some interpretations, the demise of elegance in harsh realities. His thematic focus often remained on nature, particularly his beloved gardens, which provided an endless source of inspiration for his explorations of light and colour.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Curt Herrmann's artistic output can be broadly categorized. His early phase was dominated by portraits executed with academic proficiency. The influence of Japonisme then introduced new compositional ideas and a flatter perspective. The most significant phase is his Neo-Impressionist period, where his canvases are characterized by:

1. Divisionist Technique: The application of small dots or strokes of pure colour, intended to mix optically in the viewer's eye. This created a vibrant, luminous effect.

2. Emphasis on Light: A primary concern was the depiction of natural light and its effects on colour and atmosphere. His garden scenes, often painted en plein air or based on outdoor studies, excel in capturing the brilliance of sunlight.

3. Harmonious Colour Palettes: While using pure colours, Herrmann aimed for overall harmony, carefully balancing warm and cool tones to create a cohesive and aesthetically pleasing image.

4. Subjects: Gardens, flowers, landscapes, and portraits remained his primary subjects. His garden at Pretzfeld, for instance, became a recurring motif. Even in his portraits, the Neo-Impressionist technique was often applied, giving them a modern sensibility.

His work can be compared and contrasted with other artists of his time. While sharing the Neo-Impressionist technique with French artists like Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, and the Belgian Théo van Rysselberghe, Herrmann's interpretation often possessed a distinctly German sensibility, perhaps a certain lyrical quality or a more introspective mood in some works. Compared to German Impressionists like Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt, or Lovis Corinth, Herrmann's approach was more systematic and overtly modern in its embrace of colour theory. He was less concerned with capturing the fleeting moment in broad, gestural strokes (as in Impressionism) and more focused on the analytical construction of light and colour.

Legacy and Influence

Curt Herrmann passed away on November 13, 1929, in Erlangen. His death occurred just before the art world in Germany would face the severe repression of the Nazi regime, which branded modern art, including Neo-Impressionism and Expressionism, as "degenerate." This undoubtedly affected the posthumous recognition of many artists of his generation.

Nevertheless, Curt Herrmann's contributions remain significant. He was a crucial conduit for Neo-Impressionist ideas in Germany, both through his own paintings and his advocacy for French artists. His involvement in the Berlin Secession and the Freie Secession helped to break the stranglehold of academic art and create a more open environment for modernism. His art school for women also played a part in expanding access to artistic training.

While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his Secession colleagues like Liebermann or Corinth, or the French Neo-Impressionists he admired, Herrmann's oeuvre represents an important chapter in German modernism. He was a dedicated artist who embraced new ideas, tirelessly worked to promote them, and created a body of work that celebrates the beauty of nature through the innovative lens of light and colour. His paintings can be found in various German museums, and occasional exhibitions help to re-evaluate his position in art history.

His influence can be seen in his role as an educator and as a model for other German artists who explored Post-Impressionist techniques. While direct stylistic lineage to later movements like German Expressionism (Die Brücke artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, or Der Blaue Reiter's Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc) might be less direct, his efforts to champion the avant-garde helped pave the way for their more radical departures. He fostered an atmosphere where experimentation was valued, which was essential for the subsequent flourishing of diverse modern art forms in Germany before the 1930s.

In conclusion, Curt Herrmann was more than just a painter; he was an active cultural agent. His artistic journey reflects the dynamic intellectual and creative exchanges that characterized European art at the turn of the century. From the academic halls of Munich to the avant-garde circles of Berlin and Paris, Herrmann navigated the shifting currents of modern art, leaving behind a legacy as a pioneer of German Neo-Impressionism and a steadfast supporter of artistic progress. His dedication to capturing the ephemeral beauty of the world in points of pure, radiant colour ensures his place in the annals of art history.