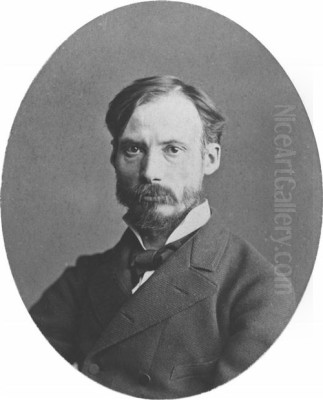

Pierre-Auguste Renoir stands as one of the most beloved and significant figures in the history of Western art. A leading painter in the development of the Impressionist style, his work is celebrated for its vibrant light, saturated color, and intimate portrayal of people and leisure. Spanning a long and prolific career from the 1860s until his death in 1919, Renoir's art evolved, yet consistently conveyed a sense of warmth, sensuality, and the simple joys of life. His canvases, filled with bustling Parisian scenes, charming portraits, and voluptuous nudes, continue to captivate audiences worldwide.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was born on February 25, 1841, in Limoges, a city in central France known for its porcelain production. He came from a modest background; his father, Léonard Renoir, was a tailor, and his mother, Marguerite Merlet, was a seamstress. Seeking better opportunities, the family moved to Paris around 1845, settling near the Louvre museum, which would later become a significant source of inspiration for the young artist.

Renoir showed artistic talent from an early age. His family's financial situation meant a formal education was brief. At the age of 13, he began an apprenticeship at the Lévy Frères porcelain factory. Here, he learned the delicate craft of painting designs on china. This early training honed his skill with a brush and instilled an appreciation for decorative qualities and luminous color, characteristics that would echo throughout his later work. He reportedly excelled at this work, painting floral motifs and even copies of Rococo masters like François Boucher and Jean-Antoine Watteau onto the fine porcelain.

The industrialization of porcelain production eventually made hand-painting less viable, and Renoir had to seek other work, including painting fans and decorative window blinds. However, his ambition lay in fine art. During his time at the factory and afterward, he took drawing lessons and frequently visited the Louvre to study the works of the Old Masters, particularly the French Rococo painters whose grace and sensuality appealed to him, as well as masters of color like Eugène Delacroix and the Realist Gustave Courbet.

Formal Training and Impressionist Connections

Determined to become a serious painter, Renoir saved enough money to enroll at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1862. More significantly, he also joined the private studio of Charles Gleyre, a Swiss academic painter. While Gleyre's traditional teaching methods held limited appeal for Renoir, the studio proved crucial for the connections he made.

It was in Gleyre's studio that Renoir befriended three other young artists who would become central figures in the Impressionist movement: Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. They shared a dissatisfaction with the rigid academic conventions taught at the École and Gleyre's studio. They were drawn to painting modern life and capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, often working outdoors, or en plein air.

This group, sometimes joined by Camille Pissarro and occasionally Paul Cézanne and Armand Guillaumin, formed the nucleus of what would become Impressionism. They often painted together in the Forest of Fontainebleau and along the Seine River, particularly at La Grenouillère, a popular boating and bathing spot. These early collaborations were vital for developing the techniques associated with Impressionism: broken brushwork, a bright palette, and an emphasis on capturing immediate visual sensations rather than detailed, finished surfaces. Renoir's early works from this period show the influence of Courbet's Realism but increasingly incorporate the lighter touch and brighter colors of his friends.

The Impressionist Movement and Early Success

The 1860s and early 1870s were years of struggle for Renoir and his friends. Their innovative style was frequently rejected by the official Paris Salon, the dominant venue for exhibiting art and gaining recognition. Renoir experienced occasional acceptance, such as with his portrait Lise with a Parasol (1867), featuring his then-lover Lise Tréhot, but rejections were common, and financial hardship was a constant reality. Frédéric Bazille, who came from a wealthier family, often supported his friends, sharing his studio and resources.

Frustrated by the Salon system, Renoir, Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and others decided to organize their own independent exhibition. This landmark event took place in April 1874 in the former studio of the photographer Nadar. It was this exhibition that inadvertently gave the movement its name, derived from a critic's mocking review of Monet's painting Impression, Sunrise.

Renoir contributed several works to the first Impressionist exhibition, including the now-famous La Loge (The Theatre Box) (1874). This painting, depicting a fashionable couple (modeled by Renoir's brother Edmond and a Montmartre model Nini Lopez) in a theatre box, exemplifies his early Impressionist style: vibrant color, loose brushwork capturing the textures of fabric and flesh, and a sense of immediacy and modern Parisian life.

He participated in the second (1876) and third (1877) Impressionist exhibitions as well. The 1876 show featured one of his undisputed masterpieces, Bal du moulin de la Galette (Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette). This large canvas depicts a lively Sunday afternoon dance at a popular outdoor venue in Montmartre. It is a quintessential Impressionist work, capturing the dappled sunlight filtering through the trees, the swirling movement of the dancers, and the cheerful atmosphere of Parisian leisure. Renoir masterfully blends figure painting with landscape elements, using flickering brushstrokes and a vibrant palette to convey the scene's energy and light. Another notable work from this period is The Swing (La Balançoire) (1876), which similarly explores effects of sunlight on figures in a garden setting.

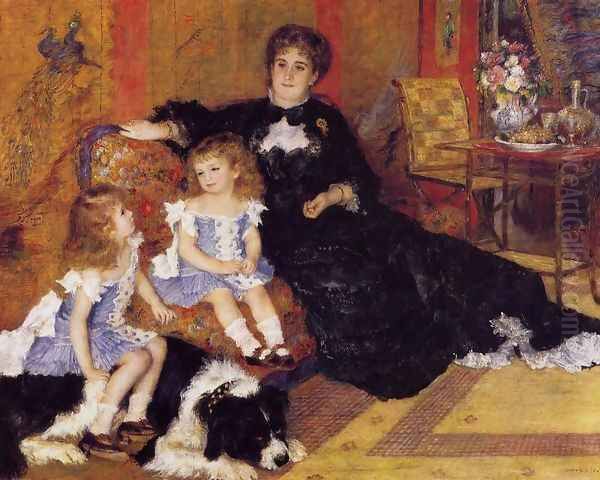

Despite the critical controversy surrounding the Impressionist exhibitions, Renoir began to achieve a degree of success, particularly with portrait commissions. His charm and sociable nature helped him cultivate patrons among the Parisian bourgeoisie. His 1878 portrait Madame Georges Charpentier and Her Children was accepted at the official Salon of 1879 and received favorable reviews, marking a turning point in his career and financial stability. This success led him to distance himself somewhat from the Impressionist group exhibitions after 1877, seeking recognition through the more established Salon system for a time.

A Crisis and a Change in Direction: The "Ingres" Period

Around 1881, Renoir experienced what art historians often call a "crisis" regarding Impressionism. He began to feel that the emphasis on fleeting effects and loose brushwork neglected the underlying structure and solidity of form found in the art of the Old Masters he admired. He felt he had "wrung Impressionism dry" and needed a new direction that incorporated more classical principles of drawing and composition.

This period of reassessment coincided with extensive travels. In 1881, he journeyed to Algeria, following in the footsteps of Delacroix, where he was captivated by the exotic light and colors. Later that year and into 1882, he traveled to Italy, visiting Venice, Florence, Rome, Naples, and Pompeii. He was deeply impressed by the Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael, and the clarity of form in ancient Roman frescoes. He wrote to his dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, about the "wisdom" and "simplicity" he found in Pompeian painting. He also encountered the work of the 19th-century Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, whose precise linearity offered a stark contrast to Impressionist technique.

These experiences prompted a significant shift in Renoir's style during the mid-1880s, often referred to as his "sour" period (période aigre) or "Ingres" period. His brushwork became tighter, outlines became more defined, surfaces smoother, and his palette sometimes cooler. He focused more intently on drawing and structure. This is evident in works like The Large Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses), painted between 1884 and 1887. This monumental canvas depicts several female nudes by the water, rendered with clear contours and sculptural solidity, drawing inspiration from classical sculpture and Renaissance painting, particularly a relief by François Girardon at Versailles.

Other works from this period, like Dance in the City and Dance in the Country (both 1883), commissioned by Durand-Ruel, also show this move towards greater definition and formality, though Dance in the Country, featuring his future wife Aline Charigot, retains more warmth and spontaneity. Luncheon of the Boating Party (1881), completed just before this stylistic shift fully took hold, masterfully balances Impressionist light and atmosphere with a complex, stable composition and well-defined figures, perhaps foreshadowing his search for greater structure.

This stylistic change was met with mixed reactions. Some critics and patrons preferred his earlier Impressionist works, finding the new style harsh or dry. However, Renoir felt it was a necessary evolution in his artistic development, a way to integrate the lessons of the past with the innovations of Impressionism.

Later Years: Synthesis, Sensuality, and the South

By the late 1880s and early 1890s, Renoir began to move away from the relative severity of his "Ingres" period. His later style represents a synthesis, blending the vibrant color and light of his Impressionist years with the more solid forms and classical sense of composition he had explored. His brushwork became fluid again, though often broader and richer than in his earlier Impressionist phase.

A key characteristic of his late work is a return to a warmer, more luminous palette, often dominated by reddish, pink, and orange tones. This is particularly evident in his numerous depictions of the female nude, which became a central theme. These late nudes are typically voluptuous, painted with a sensuous appreciation for flesh tones and rounded forms, often set in idyllic, timeless landscapes. Works like Sleeping Bather (1897) or the many bathers painted in the early 20th century exemplify this late style, which sometimes evokes the spirit of Rococo masters like Boucher or the Venetian Renaissance painter Titian.

Family life also remained an important subject. He frequently painted his wife Aline and their three sons: Pierre (born 1885), Jean (born 1894, who would become a celebrated filmmaker), and Claude (born 1901, known as "Coco"). Portraits like Gabrielle and Jean (1895), featuring the family's beloved nanny Gabrielle Renard with the young Jean, radiate warmth and intimacy. Flowers, particularly roses, and sun-drenched landscapes of Southern France also feature prominently in his late work.

Around 1892, Renoir began suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that would progressively worsen over the years. Seeking a warmer climate to ease his pain, he started spending more time in the south of France, eventually buying property, Les Collettes, in Cagnes-sur-Mer near the Mediterranean coast in 1907. Despite increasing disability, which eventually confined him to a wheelchair and deformed his hands, Renoir's determination to paint never wavered.

In his final years, unable to grip brushes easily, he had them strapped to his wrists. He continued to produce works filled with light and color, focusing on nudes, portraits, still lifes, and the landscape around his home. He even explored sculpture, collaborating with the young Catalan artist Richard Guino, who translated Renoir's ideas and drawings into three-dimensional forms, most notably the sculpture Venus Victrix. His visit to the Louvre in 1919, shortly before his death, to see his own work hanging among the masters, was a testament to the recognition he had achieved.

Themes and Artistic Philosophy

Throughout his diverse stylistic phases, certain themes and attitudes remained constant in Renoir's work. Above all, his art is a celebration of beauty, pleasure, and the fullness of life. He famously remarked, "For me, a picture should be something likeable, joyous, and pretty, yes pretty! There are enough troublesome things in life without inventing others." This philosophy permeates his choice of subjects: cheerful social gatherings, beautiful women, rosy-cheeked children, abundant flowers, and sunlit landscapes.

The female figure was arguably his most persistent subject. From portraits of society ladies and intimate depictions of his wife and models, to his numerous nudes, Renoir explored femininity in all its aspects. His approach was typically sensual and appreciative, focusing on warmth, softness, and vitality rather than psychological complexity or dramatic tension. While some later critics have debated the representation of women in his work, his contemporaries largely saw his paintings as joyful affirmations of life and beauty.

Renoir was a master of color. His ability to capture the effects of light on surfaces, particularly human skin, was exceptional. He often used complementary colors placed side-by-side to create vibrancy, and his palettes ranged from the cool blues and greens of his early landscapes to the fiery reds and oranges of his late nudes. His technique, whether the broken brushwork of Impressionism or the smoother modeling of his Ingres period, always served his goal of creating luminous, harmonious images.

Unlike some of his Impressionist colleagues like Degas or Pissarro, Renoir generally avoided overtly political or social commentary in his work. His focus remained on the personal, the intimate, and the aesthetically pleasing. He sought to create a world of warmth and beauty on canvas, an escape from the difficulties of modern life.

Personal Life and Relationships

Renoir's personal life was intertwined with his art. His relationship with Lise Tréhot in the late 1860s resulted in numerous paintings, including Lise with a Parasol. They had a daughter, Jeanne, born in 1870, though Renoir did not formally acknowledge her.

His most significant relationship was with Aline Charigot, a seamstress twenty years his junior, whom he met around 1880. She became a frequent model, appearing prominently in Luncheon of the Boating Party and Dance in the Country. They married in 1890 and had three sons: Pierre, an actor; Jean, the renowned film director; and Claude ("Coco"), who became a ceramicist. Family life provided Renoir with constant inspiration, and Aline and the children feature in many tender portraits. Gabrielle Renard, a cousin of Aline's who came to live with the family as a nanny, also became a favorite model and close companion, appearing in over 200 paintings.

Renoir maintained lifelong friendships with fellow artists, particularly Claude Monet. Despite their different artistic paths after the main Impressionist period, their mutual respect and affection endured. He was also supported by key patrons and dealers, most notably Paul Durand-Ruel, who championed the Impressionists when few others would, and collectors like Victor Chocquet and the Charpentier family. While described as sociable and charming, Renoir also valued his privacy and the tranquility of family life, especially in his later years. Some accounts suggest a complex personality, perhaps holding conservative social views that seemed at odds with his revolutionary artistic practice, but his art consistently speaks of optimism and a love for humanity.

Legacy and Influence

Pierre-Auguste Renoir died at his home in Cagnes-sur-Mer on December 3, 1919, at the age of 78. He left behind an enormous body of work, estimated at over four thousand paintings, as well as pastels, drawings, watercolors, and sculptures. He is universally recognized as a leading figure of Impressionism and one of the great masters of modern art.

His influence on subsequent generations of artists was profound. His emphasis on color and sensuous form resonated with Fauvist painters like Henri Matisse and André Derain. Pablo Picasso deeply admired Renoir, particularly his later works, seeing in them a connection to a timeless, classical tradition of figure painting. Artists like Pierre Bonnard and Aristide Maillol also drew inspiration from his rich color and celebration of life.

Today, Renoir's paintings are highlights of major museum collections around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, and the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia (which holds the largest single collection of his works). His most famous paintings, such as Bal du moulin de la Galette and Luncheon of the Boating Party, are among the most iconic images in art history.

While his later, highly sensual nudes have occasionally drawn criticism in contemporary discourse, Renoir's overall reputation remains immense. He is celebrated for his technical mastery, his extraordinary use of color, and, perhaps most importantly, for the enduring sense of joy, warmth, and beauty that radiates from his canvases. He captured the fleeting moments of modern life with Impressionist vibrancy, yet rooted his art in a deep appreciation for tradition and the timeless appeal of the human form, creating a body of work that continues to enchant and inspire.