Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes stands as a monumental figure in nineteenth-century French art, a painter whose unique vision bridged the classical tradition with the burgeoning currents of modernism. Celebrated primarily for his serene and allegorical murals, Puvis developed a distinctive style characterized by simplified forms, muted palettes, and a profound sense of timelessness. Though sometimes misunderstood in his own era, his work exerted a considerable influence on a diverse range of artists, from Symbolists and Post-Impressionists to the early pioneers of twentieth-century abstraction.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on December 14, 1824, in Lyon, France, Pierre-Cécile Puvis de Chavannes hailed from a family with a background in mining engineering. His early education took place at the Amiens College and later at the prestigious Lycée Henri IV in Paris. Initially, he was expected to follow in his father's professional footsteps, pursuing a career in engineering. However, a serious illness and a subsequent recuperative trip to Italy in 1847 proved to be a turning point. The art and landscapes of Italy ignited a passion for painting, altering the course of his life.

Upon his return to Paris, Puvis embarked on his artistic training. He briefly studied with Henri Scheffer, a painter known for his historical and genre scenes. He also spent a short period in the studio of the Romantic master Eugène Delacroix, whose vibrant color and dramatic compositions, though influential in the broader art world, seemed to have less direct impact on Puvis's developing aesthetic. A more significant, albeit also brief, period of study was undertaken with Thomas Couture, a prominent academic painter whose atelier attracted many aspiring artists, including Édouard Manet.

Despite these formal studies, Puvis was largely self-taught, meticulously studying the Old Masters, particularly the Italian Renaissance fresco painters like Giotto and Piero della Francesca. Their influence is evident in the clarity of form, the emphasis on composition, and the mural-like quality that would come to define his own work. He sought to create an art that was both monumental and deeply imbued with meaning, moving away from the prevailing Realism of Gustave Courbet and the nascent Impressionist movement.

The Emergence of a Unique Style

Puvis de Chavannes's early career was marked by a struggle for recognition. His submissions to the official Paris Salon, the most important art exhibition in France, were frequently rejected. This period of obscurity, however, allowed him the freedom to develop his highly personal artistic language. He eschewed the detailed naturalism and dramatic flair favored by many of his contemporaries, opting instead for a style that emphasized harmony, order, and a meditative calm.

His figures are often statuesque and idealized, rendered with a deliberate simplification of form that lends them an archaic, almost timeless quality. His color palettes are typically subdued, dominated by cool blues, grays, pale ochres, and soft greens, creating an atmosphere of serene contemplation. Puvis mastered the art of "peinture claire" (light painting), using matte finishes and limited tonal variations to evoke the effect of fresco, even in his easel paintings. This technique contributed to the flat, decorative quality of his surfaces, a characteristic that would resonate strongly with later modernists.

A significant breakthrough came in 1861 when his large-scale allegorical paintings, Concordia (Peace) and Bellum (War), were exhibited at the Salon. Though initially purchased by the state, they were later returned to the artist due to a lack of suitable public space. Puvis repurchased them and eventually donated them to the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, where they remain key examples of his early mural style. These works, with their frieze-like compositions and symbolic figures, established him as a major decorative painter.

Major Mural Cycles: Defining Public Spaces

It was in the realm of mural painting that Puvis de Chavannes achieved his most profound and lasting impact. He received numerous commissions to decorate public buildings throughout France, transforming civic and cultural spaces with his grand allegorical visions. These murals were not mere embellishments but integral parts of the architecture, designed to harmonize with their surroundings and convey lofty ideals.

One of his most celebrated mural cycles is The Life of Saint Genevieve, executed for the Panthéon in Paris. This extensive project, undertaken in stages between 1874 and 1878, and then again from 1893 to 1898, depicts scenes from the life of the patron saint of Paris. Works like Saint Genevieve as a Child in Prayer and Saint Genevieve Provisioning Paris showcase his ability to convey narrative and spiritual depth through simplified forms and a serene, almost ethereal atmosphere. The figures possess a quiet dignity, and the landscapes are rendered with a poetic abstraction that transcends mere representation.

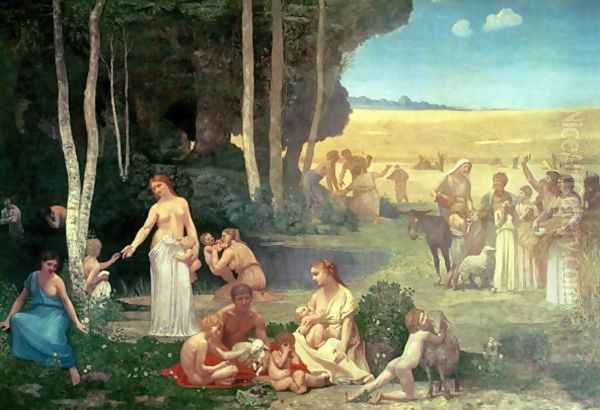

Another significant commission was for the grand amphitheater of the Sorbonne in Paris, where he painted The Sacred Grove, Beloved of the Arts and the Muses (1884-1889). This idyllic scene, populated by allegorical figures representing various arts and sciences, embodies Puvis's vision of a harmonious classical world. The composition is balanced and rhythmic, the colors are soft and luminous, and the overall effect is one of profound tranquility and intellectual aspiration.

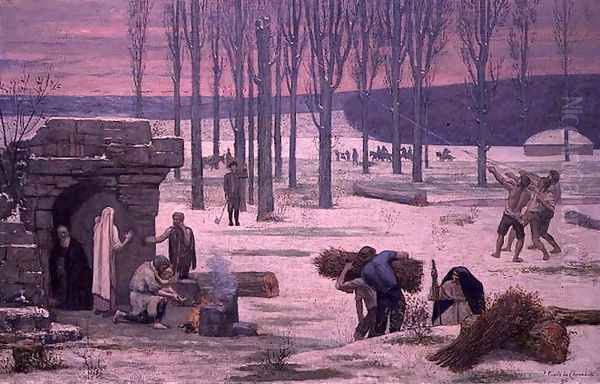

His murals for the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, including Antique Vision, Christian Inspiration, and The Rhône and the Saône (completed 1886), further demonstrate his mastery of large-scale decorative painting. He also created important works for the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) in Paris, such as Summer and Winter, and for the Boston Public Library in the United States, with a series depicting The Muses Welcoming the Genius of Enlightenment (1893-1896). These international commissions underscored his growing reputation.

Other notable murals include Work and Rest, initially conceived for the Salon of 1863 and later adapted for the Musée de Picardie, and Pro Patria Ludus (For the Fatherland, Games), also for Amiens, which celebrates youthful vigor and patriotic spirit in a classical setting.

Key Easel Paintings and Their Themes

While best known for his murals, Puvis de Chavannes also produced a significant body of easel paintings. These works often explored similar themes of allegory, mythology, and idealized nature, and they shared the stylistic characteristics of his larger decorative schemes.

The Poor Fisherman, painted in 1881 and now in the Musée d'Orsay, is perhaps his most famous easel painting. It depicts a lone fisherman in a desolate, melancholic landscape, his gaunt figure and the somber tones conveying a sense of quiet resignation and profound poverty. The painting's stark simplicity and emotional depth resonated with many, including younger artists like Georges Seurat, who admired its formal rigor and expressive power. The work was controversial at the time for its perceived bleakness and lack of conventional beauty, yet it became an icon of Symbolist art.

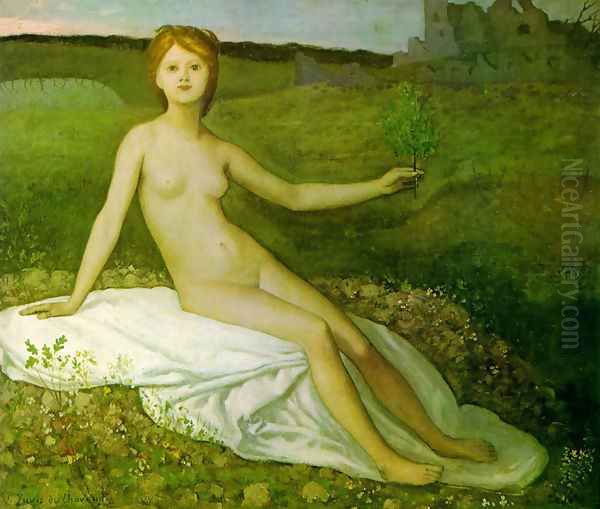

Hope (versions from 1872) presents a more optimistic vision, typically featuring a young, nude female figure holding an olive branch, silhouetted against a landscape that often includes ruins, symbolizing renewal after devastation, likely a reference to the Franco-Prussian War. The delicate rendering and serene mood are characteristic of Puvis's approach.

Young Girls by the Seaside (1879) is another celebrated work, showcasing his ability to create idyllic scenes with a timeless quality. The figures are graceful and statuesque, their forms simplified and their gestures restrained. The pale, harmonious colors and the flattened perspective contribute to the painting's decorative effect.

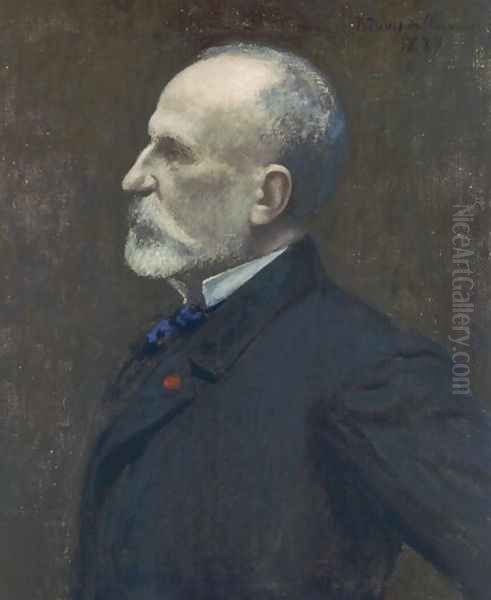

Other important easel paintings include The Dream (1883), which evokes a mysterious, otherworldly atmosphere, and The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (c. 1869), a stark and dramatic composition that, while atypical in its violence, still retains Puvis's characteristic formal simplification. His Self-Portrait, housed in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, offers a dignified and introspective image of the artist.

Symbolism and the "Peinture Claire"

Puvis de Chavannes is widely regarded as a leading figure of the Symbolist movement, although he never formally aligned himself with any particular group. Symbolism, which emerged in the late nineteenth century as a reaction against Realism and Impressionism, sought to express ideas, emotions, and spiritual truths through suggestive imagery and symbolic meaning rather than direct representation. Puvis's art, with its emphasis on allegory, dreamlike atmospheres, and universal themes, perfectly embodied the Symbolist ethos.

His "peinture claire" – the use of light, often pale colors and a matte finish to emulate the look of frescoes – was crucial to his aesthetic. This technique not only enhanced the decorative quality of his work but also contributed to its sense of unreality and timelessness. By reducing detail and simplifying forms, he encouraged viewers to look beyond the surface and contemplate the underlying ideas. Artists like Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau, key figures in Symbolism, shared this interest in the evocative power of art, though their visual languages differed significantly from Puvis's more classical restraint.

Puvis's figures often seem to exist outside of specific historical time, inhabiting an idealized realm of myth and allegory. His landscapes are not literal depictions of particular places but rather generalized, poetic settings that enhance the mood and meaning of the scene. This approach distinguished him from the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, who were primarily concerned with capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere in the observable world.

Controversies and Critical Reception

Despite his eventual success and numerous public commissions, Puvis de Chavannes's art was not without its detractors. His style was so unconventional for its time that it often provoked bewilderment and criticism. Some academic critics found his figures too flat, his drawing too simplified, and his colors too pale and lacking in vibrancy. They accused him of archaism and a deliberate rejection of the technical virtuosity prized by the Salon.

Satirists sometimes caricatured his work, comparing his figures to "paper cut-outs" or suggesting they lacked anatomical correctness. The very qualities that made his art innovative – its anti-naturalism, its decorative flatness, and its emphasis on suggestion rather than explicit detail – were often the targets of negative critique.

However, Puvis also garnered significant support, particularly from progressive critics and younger artists who recognized the originality and power of his vision. Writers like Théophile Gautier and Joris-Karl Huysmans, though the latter was sometimes ambivalent, acknowledged his unique contribution. The poet Stéphane Mallarmé, a central figure in the Symbolist literary movement, was an admirer. As the nineteenth century drew to a close, Puvis's reputation grew, and he came to be seen as a pivotal figure, a bridge between tradition and modernity.

The Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and Artistic Independence

In 1890, Puvis de Chavannes played a key role in a significant development in the Parisian art world. Discontent with the increasingly rigid and conservative policies of the official Salon (run by the Société des Artistes Français), Puvis, along with other prominent artists like Ernest Meissonier, Auguste Rodin, and Carolus-Duran, led a secession. They revived the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, establishing a new, more liberal annual exhibition, often referred to as the "Salon du Champ de Mars."

Puvis served as president of this new society from its inception until his death. The creation of the Société Nationale provided an alternative venue for artists who felt marginalized by the official Salon, fostering a greater diversity of artistic expression. This move demonstrated Puvis's commitment to artistic independence and his support for a more inclusive art world. It was a significant step away from the monolithic authority of the traditional Salon system, prefiguring the rise of independent Salons like the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d'Automne in the years to come.

Influence on Contemporaries and the Next Generation

The impact of Puvis de Chavannes on subsequent generations of artists was profound and wide-ranging. His emphasis on formal simplification, decorative composition, and expressive content resonated deeply with many who were seeking alternatives to academic naturalism and Impressionist empiricism.

Paul Gauguin was a fervent admirer, seeing in Puvis's work a precedent for his own anti-naturalistic, Symbolist art. Gauguin's use of flat planes of color, simplified forms, and evocative subject matter in paintings like The Vision After the Sermon owes a debt to Puvis's example. Georges Seurat, the pioneer of Neo-Impressionism, also held Puvis in high esteem, particularly admiring the compositional rigor and monumental quality of works like The Poor Fisherman. Seurat's own large-scale compositions, such as A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, share Puvis's concern for formal order and a sense of timelessness, albeit achieved through very different technical means.

Vincent van Gogh, during his time in Paris and later in Arles, was aware of Puvis's work. He was particularly struck by Puvis's mural Inter artes et naturam (Between Art and Nature) and praised its modern sensibility and influence on younger artists. Van Gogh's own expressive use of color and form, while distinct, shared a desire to imbue art with deeper emotional and spiritual meaning.

The Nabis, a group of young Post-Impressionist artists active in the 1890s, including Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, and Édouard Vuillard, were significantly influenced by Puvis. Maurice Denis, in particular, famously declared that a painting, "before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order." This statement, a cornerstone of modernist art theory, reflects the lessons the Nabis drew from Puvis's emphasis on the decorative and formal qualities of painting.

Even artists who would become giants of twentieth-century modernism, such as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, acknowledged Puvis's importance. Matisse's early work, with its emphasis on flat planes of color and decorative harmony, shows an affinity with Puvis. Picasso, during his Blue Period, created compositions with a similar mood of melancholy and simplification of form that recall Puvis's figures. Aristide Maillol, the sculptor, also found inspiration in the classical serenity and monumental simplicity of Puvis's figures.

Other artists touched by his influence include the Swiss Symbolist Ferdinand Hodler, whose rhythmic compositions and allegorical figures share common ground with Puvis, and the Belgian Symbolist Fernand Khnopff. Georges Rouault, known for his deeply spiritual and expressionistic works, also passed through a phase where Puvis's influence was discernible.

Puvis de Chavannes and the Nabis

The connection between Puvis de Chavannes and the Nabis (Hebrew for "prophets") is particularly noteworthy. This group, which included Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Paul Sérusier, and Édouard Vuillard, sought to revitalize painting by emphasizing its spiritual and decorative potential. They were drawn to Puvis's anti-naturalism, his simplified forms, and his ability to create evocative, dreamlike atmospheres.

Maurice Denis was a vocal champion of Puvis, seeing him as a crucial link between the classical tradition and modern art. Denis admired Puvis's ability to synthesize observation of nature with imaginative design, creating works that were both monumental and deeply personal. The Nabis' interest in mural painting and decorative arts also found a precedent in Puvis's career. They, too, sought to integrate art into everyday life through decorative panels, stained glass, and theater design, echoing Puvis's commitment to public art. Sérusier's The Talisman, painted under Gauguin's guidance, with its almost abstract rendering of landscape, reflects the move towards synthesis and subjective expression that Puvis had pioneered in his own way.

International Resonance

Puvis de Chavannes's influence was not confined to France. His work gained international recognition, and his murals for the Boston Public Library were a testament to his transatlantic reputation. Artists in other countries also looked to his example. In the United States, muralists like John La Farge and Kenyon Cox were influenced by his approach to large-scale decorative painting.

His art was exhibited internationally, and reproductions of his work circulated widely, further disseminating his ideas. The universal themes and timeless quality of his art transcended national boundaries, appealing to a broad audience seeking an alternative to the perceived materialism and superficiality of modern life. His impact was felt in countries like Belgium, Switzerland (with artists like Hodler), and even Scandinavia, where artists like Edvard Munch, though developing a highly personal expressionism, were part of the broader Symbolist current that Puvis helped to shape.

Personal Glimpses: The Man Behind the Art

Despite his public prominence, Puvis de Chavannes was known as a reserved and dignified individual. He dedicated himself to his art with a quiet intensity. For many years, he had a close relationship with the Romanian princess Marie Cantacuzène, whom he had known since the 1850s and eventually married in 1897, just a year before his death. She was a supportive companion and often posed for him.

An interesting, though perhaps less central, aspect of his personal life involved Suzanne Valadon. Before she became a notable painter in her own right and the mother of Maurice Utrillo, Valadon modeled for several artists in Montmartre, including Puvis de Chavannes, as well as Renoir and Toulouse-Lautrec. While the exact nature of their relationship is subject to some speculation, her presence in the bohemian art circles of Paris connects Puvis to a younger, more avant-garde generation.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Puvis de Chavannes continued to work on major commissions and remained a respected figure in the art world. He was made a Commander of the Legion of Honour in 1889. His dedication to his craft was unwavering, and he maintained his distinctive style, refining his vision of a serene, ordered, and spiritually resonant art.

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes died in Paris on October 24, 1898, at the age of 73, shortly after the death of his wife. He left behind a substantial body of work that had already begun to reshape the landscape of modern art. His legacy lies not only in his magnificent murals and easel paintings but also in the profound influence he exerted on a generation of artists who would carry the torch of modernism into the twentieth century.

Re-evaluation in Art History

For a period in the mid-twentieth century, as abstract art and other avant-garde movements took center stage, Puvis de Chavannes's reputation somewhat receded. His art, with its classical overtones and allegorical content, seemed out of step with the prevailing modernist narratives. However, in more recent decades, art historians have re-evaluated his contribution, recognizing him as a more complex and pivotal figure than previously acknowledged.

Scholarly exhibitions and publications have shed new light on his work, emphasizing his innovative approach to composition, his role in the Symbolist movement, and his crucial influence on early modernism. He is no longer seen merely as a conservative academic painter but as a visionary who forged a unique path, synthesizing tradition and innovation. His exploration of "art for art's sake" in terms of decorative harmony, combined with his profound subject matter, marks him as a critical transitional figure. His ability to create monumental public art that also possessed a deep personal vision has been increasingly appreciated.

Conclusion: A Lasting Imprint

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes remains an artist of enduring significance. His quest for a timeless, universal art, expressed through simplified forms, harmonious colors, and evocative symbolism, set him apart from his contemporaries and paved the way for many of the key developments in modern art. From the grand murals that adorn public buildings in France and America to intimate easel paintings like The Poor Fisherman, his work continues to resonate with its quiet power and profound beauty. As a master of decorative painting, a leading figure of Symbolism, and an inspiration to artists as diverse as Seurat, Gauguin, Denis, Matisse, and Picasso, Puvis de Chavannes carved a unique and indelible place in the history of art. His vision of an art that could be both monumental and meditative, public and personal, classical and modern, ensures his lasting importance.