Ramsay Richard Reinagle stands as a notable, albeit complex, figure in the landscape of British art during the late Georgian and early Victorian periods. Born in 1775 and living until 1862, his long career spanned significant shifts in artistic taste and practice. He achieved considerable recognition as a painter of landscapes, portraits, and animals, following in the footsteps of his equally artistic family. However, his legacy is permanently marked by a significant professional scandal that curtailed his formal standing within the art establishment. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, achievements, relationships, and the controversy that ultimately defined his later career.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Ramsay Richard Reinagle was born into an artistic dynasty. His father, Philip Reinagle (1749–1833), was a versatile and respected artist, initially known for portraiture as a student of Allan Ramsay, but later gaining fame for his animal paintings, particularly sporting dogs and birds, as well as landscapes and masterful copies of Dutch Masters. This familial environment undoubtedly provided the young Ramsay Richard with an immersive artistic upbringing. He received his primary training directly from his father, absorbing the technical skills and diverse subject interests that characterized Philip's output.

Evidence of his precocious talent emerged early. Reinagle began exhibiting at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London as early as 1788, when he was just thirteen years old. This debut at such a young age signalled a promising start, placing him within the orbit of the leading artists of the day, such as Sir Joshua Reynolds, the Academy's founding president, and his successor Benjamin West. His initial submissions likely reflected his father's influence, potentially including portraits or animal studies.

The artistic milieu of late 18th-century London was vibrant. Besides the towering figures of Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough (who died in 1788), artists like George Romney were active portraitists, while landscape painting was gaining increasing status, influenced by figures like Richard Wilson and the burgeoning interest in the Picturesque. Reinagle entered this world equipped with solid foundational skills inherited and learned from his father.

The Grand Tour: Italy and Dutch Influences

Like many ambitious British artists of his era, Reinagle sought to broaden his horizons and refine his skills through travel, undertaking a version of the Grand Tour. He journeyed to Italy, spending significant time particularly in Rome, the epicentre of classical antiquity and Renaissance art. This experience was transformative, exposing him to the masterpieces of Italian art and the sun-drenched landscapes that had inspired generations of painters, including the seminal French landscape artists Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose idealized visions of the Roman Campagna were highly influential.

During his Italian sojourn, Reinagle diligently sketched the scenery, capturing the light, topography, and architectural ruins. These sketches would serve as invaluable source material for finished oil paintings produced later in his London studio. His time in Italy solidified his commitment to landscape painting, particularly scenes imbued with a classical or picturesque sensibility. Works depicting Italian lakes and countryside became a significant part of his oeuvre.

Reinagle also travelled to the Netherlands. This journey was crucial for deepening his understanding of the Dutch Golden Age masters, whose work his father admired and copied. He studied the landscapes of Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema, known for their naturalistic depictions of the Dutch countryside, and the animal paintings of artists like Paulus Potter. This exposure reinforced his skills in detailed observation and the rendering of natural textures and atmospheric effects, complementing the more idealized approach inspired by Italy.

Ascendancy in Landscape and Portraiture

Upon returning to Britain, Reinagle established himself as a versatile and accomplished artist. His landscape paintings gained particular acclaim. He drew upon his Italian sketches to produce works characterized by careful composition, often featuring expansive views, serene bodies of water, and classical architecture, rendered with a clarity and attention to detail that appealed to contemporary tastes. An example often cited is his generic but representative Lake Scene, showcasing his ability to capture the tranquil beauty of Italian vistas with vibrant colour and skillful composition.

He did not limit himself to Italian subjects. Reinagle also painted British landscapes, contributing to the growing national pride in native scenery. His work Torrents in the Vale of the Derwent, depicting a dramatic river scene likely in Derbyshire, showcases his ability to capture the more rugged and dynamic aspects of the British landscape, perhaps responding to the burgeoning Romantic sensibility seen in the works of contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner, though Reinagle's style generally remained more controlled and detailed. Another work, Cherbourg Harbor, indicates his willingness to tackle coastal and marine subjects as well.

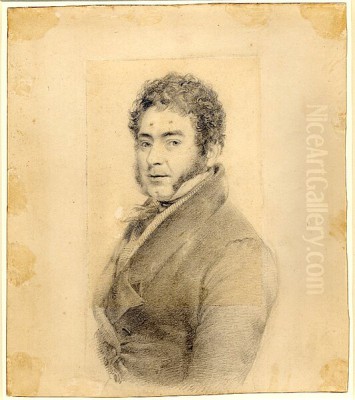

Alongside his landscapes, Reinagle continued to practice portraiture. While perhaps not reaching the heights of specialists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, he was a competent portraitist. One of his most significant works in this genre is his portrait of the fellow landscape painter John Constable (1776-1837). Painted around 1799 and now housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London, it provides a valuable early likeness of one of Britain's greatest artists, captured with sensitivity and directness. He also undertook commissions, such as portraits for the family of Francis Noel Clarke Mundy.

Master of Animal Painting

Inheriting his father's affinity for animal subjects, Ramsay Richard Reinagle also excelled in this genre. Philip Reinagle was particularly renowned for his sporting pictures, and Ramsay Richard continued this tradition, painting hunting scenes, dogs, and horses with anatomical accuracy and vitality. His skills extended to depicting birds, particularly waterfowl, reflecting a keen observation of wildlife.

These animal paintings often found a wider audience through engravings. Skilled engravers like John Scott translated Reinagle's compositions into prints, making his work accessible to a broader public beyond those who could afford original oil paintings. This practice was common at the time and significantly contributed to an artist's reputation and income. The popularity of sporting art ensured a steady demand for such images among the landed gentry.

His proficiency across landscape, portraiture, and animal painting marked him as an unusually versatile artist, capable of meeting diverse commissions and exhibiting a wide range of subjects at the Royal Academy and other venues. This versatility was a hallmark of his family's artistic practice, setting him apart from artists who specialized more narrowly.

Engagement with Watercolour

Reinagle was also actively involved in the burgeoning medium of watercolour painting. At the turn of the 19th century, watercolour was gaining status as an independent art form, moving beyond its traditional use for topographical records or preparatory sketches. Artists like Thomas Girtin and J.M.W. Turner were demonstrating its expressive potential.

Reinagle became a founding member of the Society of Painters in Water Colours (now the Royal Watercolour Society) in 1804. This society was established to promote watercolour painting and provide a dedicated exhibition venue outside the dominance of oil painting at the Royal Academy. Reinagle's involvement underscores his commitment to the medium. He served as the society's president from 1808 to 1812, a position of significant responsibility and prestige within the watercolour community, further solidifying his standing in the London art world.

His watercolour works likely mirrored the subjects of his oil paintings, including landscapes and potentially animal studies, executed with the detailed finish characteristic of early English watercolour practice, influenced perhaps by figures like Paul Sandby, often called the 'father of English watercolour'.

The Panorama Venture

The late 18th and early 19th centuries witnessed the rise of the panorama as a popular form of public entertainment and immersive visual experience. Invented by Robert Barker, these huge, circular paintings displayed in purpose-built rotundas offered audiences breathtakingly realistic, 360-degree views of famous cities, landscapes, or historical events.

Reinagle engaged directly with this popular medium. He collaborated with Thomas Edward Barker, the son of the inventor Robert Barker. Together, they established a rival panorama exhibition building on the Strand in London, competing with the original Barker establishment in Leicester Square. This venture indicates Reinagle's entrepreneurial spirit and his willingness to engage with popular visual culture beyond the confines of traditional gallery exhibitions.

Their panoramas depicted various locales, drawing on Reinagle's travels and artistic skills. Subjects included views of Rome, the Bay of Naples, Florence, Genoa, Algiers, and Paris. Creating these vast canvases required considerable skill in perspective and large-scale execution, often involving teams of assistants. Although ephemeral by nature, these panoramas were significant cultural phenomena, and Reinagle's involvement highlights his engagement with innovative forms of visual representation. These assets were later acquired by Henry Aston Barker (Thomas's brother) and John Burford in 1816.

Royal Academy Membership and Recognition

Reinagle's career progressed steadily within the established structures of the London art world. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy, the most important venue for artists seeking patronage and prestige. His consistent presence and the quality of his work led to formal recognition by the institution.

In 1814, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This was a significant step, marking him as an artist of considerable standing. He joined the ranks of other prominent artists progressing through the Academy's hierarchy. Nearly a decade later, in 1823, he achieved the highest rank, being elected a full Royal Academician (RA). This placed him among the elite of the British art establishment, alongside contemporaries like Turner, Lawrence, David Wilkie, and under the presidency of figures like Benjamin West and later Thomas Lawrence.

Membership conferred not only status but also responsibilities, including teaching in the RA Schools and participating in the selection and hanging of exhibitions. For over two decades, Reinagle enjoyed the privileges and recognition associated with being a Royal Academician, solidifying his position as a successful and respected artist. His works from this period, such as Forest Scene at Midday (1834), continued to demonstrate his technical proficiency.

A Complex Relationship: John Constable

Reinagle's path frequently crossed with that of John Constable, one of the defining figures of British landscape painting. Their relationship appears to have been initially cordial but ultimately soured, revealing differences in personality and perhaps artistic philosophy.

Evidence suggests close contact around the turn of the century. Reinagle visited Constable at his family home in East Bergholt, Suffolk, in January 1800. For a time, they reportedly shared lodgings, possibly in Suffolk, and even jointly purchased a painting attributed to the Dutch master Jacob van Ruisdael around 1800-1801. This indicates a period of shared interests and collegial interaction, perhaps based on their mutual admiration for Dutch landscape painting.

However, the relationship deteriorated. Constable, known for his deep emotional connection to nature and his revolutionary approach to landscape painting, grew critical of Reinagle. He perceived Reinagle as having a more utilitarian and perhaps commercially driven approach to art. Constable's letters suggest he came to view Reinagle as insincere or even dishonest. This clash highlights the differing artistic temperaments and possibly professional jealousies that could arise even between artists working in similar fields. Reinagle's later actions would, unfortunately, lend some credence to Constable's negative assessment.

The 1848 Scandal: A Career Derailed

The defining event of Reinagle's later career, and the one that casts the longest shadow over his legacy, occurred in 1848. In that year, Reinagle submitted a painting titled Shipping a Breeze and Rainy Weather off Hurst Castle to the Royal Academy exhibition under his own name. It was subsequently discovered that the work was not substantially his own creation.

The painting had been painted years earlier by a young, relatively unknown artist named J.W. Yarnold. Reinagle had purchased this work from a dealer, made some minor alterations, and then exhibited it as his own. When the deception came to light, it caused a major scandal within the Academy. Presenting another artist's work as one's own was a grave breach of professional ethics.

The Royal Academy conducted an investigation. Faced with irrefutable evidence, Reinagle was compelled to resign his diploma as a Royal Academician. This expulsion from the institution he had been part of for decades was a humiliating public disgrace. It effectively ended his prominent position within the British art establishment, although he continued to paint and exhibit elsewhere in his later years. The incident irrevocably tarnished his reputation.

Later Years and Legacy

After the scandal of 1848, Reinagle lived for another fourteen years, dying in Chelsea, London, in 1862 at the advanced age of 87. While stripped of his RA title, he did not cease artistic activity entirely. However, his standing was greatly diminished, and he operated more on the periphery of the art world that had once celebrated him.

Evaluating Ramsay Richard Reinagle's place in art history requires acknowledging both his considerable talents and his significant ethical lapse. For much of his career, he was a successful and respected artist, demonstrating proficiency across multiple genres. His landscapes, particularly those inspired by Italy, possess a pleasing clarity and compositional skill. His animal paintings continued a strong tradition in British art, and his portraits provide valuable records of his contemporaries. His involvement with the Watercolour Society and the panorama movement shows his engagement with different facets of the art world.

His works are held in various public collections, including the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Yale Center for British Art, and regional UK galleries, attesting to his historical significance. However, the 1848 scandal remains an unavoidable part of his story. It raises questions about artistic integrity and the pressures of maintaining a reputation in a competitive art market.

Artistic Style and Evaluation

Reinagle's style is generally characterized by detailed realism and competent draughtsmanship, reflecting his academic training under his father and his study of Dutch masters. His landscapes often feature well-structured compositions, a clear rendering of light, and careful attention to botanical and architectural detail. While proficient, his work generally lacks the innovative spark and emotional depth found in contemporaries like Turner or Constable. He represented a more conservative, though highly skilled, strand of British painting.

His Italian scenes capture the picturesque qualities sought by Grand Tourists, while his British landscapes align with the established topographical traditions, albeit executed with considerable finesse. His animal paintings demonstrate anatomical understanding and an ability to convey the textures of fur and feather. His versatility was perhaps his greatest strength, allowing him to adapt to different demands, but it may also have prevented him from developing a truly unique and powerful personal vision in any single genre.

He remains an important figure for understanding the breadth of artistic practice in Britain during his lifetime. He represents the successful academic artist, well-versed in various genres and techniques, who achieved significant recognition before falling foul of the very institution that had honoured him.

Conclusion

Ramsay Richard Reinagle's career encapsulates both the potential for success within the British art establishment of the early 19th century and the perils of professional misconduct. A talented and versatile painter descended from an artistic family, he achieved prominence through his landscapes, portraits, and animal subjects, earning the highest academic honours. His travels informed his art, particularly his popular Italianate scenes, and he engaged with various aspects of the art world, from watercolour societies to popular panoramas.

Yet, his legacy is forever intertwined with the 1848 scandal, an event that led to his expulsion from the Royal Academy and cast a long shadow over his considerable achievements. He serves as a case study in the complexities of artistic reputation, where technical skill and initial success can be overshadowed by questions of integrity. Despite this, his works survive in collections, offering valuable insights into the artistic tastes and practices of his era, securing his place, however complicated, in the annals of British art history.