Introduction: A Victorian Visionary of the Natural World

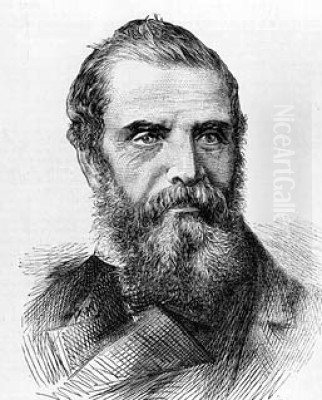

Richard Ansdell stands as a significant figure in the landscape of British Victorian art. Born in 1815 and active until his death in 1885, Ansdell carved a distinct niche for himself primarily as a painter of animals and scenes of rural life, though his repertoire also extended to historical subjects and genre painting. Hailing from Liverpool, he rose through the ranks of the art establishment, becoming a celebrated member of the Royal Academy and leaving behind a prolific body of work that captured the spirit of the British countryside, the drama of the hunt, and the quiet dignity of animal life. His detailed realism, combined with a sensitivity to atmosphere and narrative, resonated deeply with Victorian audiences, securing him considerable fame and patronage throughout his long career. This exploration delves into the life, style, influences, and legacy of this accomplished British artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings in Liverpool

Richard Ansdell entered the world on May 11, 1815, in Liverpool, then a bustling port city undergoing significant growth. He was the son of Thomas Griffiths Ansdell, whose profession involved working at the port, and Anne Jackson. Tragedy struck early in Richard's life with the premature death of his father. Subsequently, his mother remarried, and young Richard's education was entrusted to the Liverpool Blue Coat School. This institution, originally founded for orphans and underprivileged children, provided him with a foundational education.

Though circumstances might have pointed towards a trade – and indeed, he was initially apprenticed to a carpenter – Ansdell's innate artistic inclinations soon became apparent. Even during his formative years, he demonstrated a strong pull towards drawing and painting. His interests were diverse, encompassing historical narratives, the dynamic action of hunting and shooting sports, and, most enduringly, the depiction of animals. This burgeoning passion led him away from carpentry and towards the uncertain path of an artist.

A brief, formative period was spent as an apprentice under W.C. Smith, a painter based in Chatham who specialized in portraits and silhouettes. While perhaps not a direct tutelage in the grand style Ansdell would later adopt, this experience likely provided practical exposure to the artist's craft and materials. However, his true artistic education seems to have been largely self-driven, fueled by observation and practice, particularly within the artistic community of his native Liverpool.

Forging a Career: From Liverpool to London

Ansdell's public artistic journey began in his hometown. In 1835, at the age of twenty, he first exhibited his work at the Liverpool Royal Academy. This marked the start of a long and fruitful relationship with the institution. His talent was quickly recognized within the local art scene, and his reputation grew steadily. His dedication and skill culminated in his election as President of the Liverpool Royal Academy in 1845, a significant honour that underscored his standing in the regional art world.

However, the allure and prestige of the London art scene beckoned. In 1840, Ansdell made his debut at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London. This was a pivotal moment, opening his work to a national audience and the critical scrutiny of the metropolitan establishment. His submissions, often featuring the animal and rural subjects that would become his hallmark, were well-received.

From that point forward, Ansdell became a remarkably consistent contributor to the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions. Year after year, his canvases graced the walls of the RA, showcasing his evolving skill and thematic interests. Records indicate that between his debut in 1840 and his final year of exhibiting in 1885, he displayed an impressive total of 149 works at the Royal Academy alone. He also exhibited at other significant London venues, such as the British Institution, further cementing his presence in the capital's art world.

The Ansdell Style: Realism, Detail, and Rural Sentiment

Richard Ansdell's artistic style is characterized by a commitment to realism and meticulous attention to detail, particularly in his portrayal of animals. He possessed a keen observational eye, capturing the specific anatomy, textures of fur and feather, and characteristic postures of the creatures he depicted. Whether painting sporting dogs, Highland cattle, sheep, or horses, his work conveyed a sense of authenticity and deep familiarity with his subjects.

While realism formed the bedrock of his style, it was often infused with elements of Romantic sensibility and narrative. His compositions frequently told a story, whether depicting the excitement of a hunt, the quiet industry of farm life, or a moment of interaction between humans and animals. He excelled at capturing the atmosphere of the British landscape, especially the rugged beauty of the Scottish Highlands, which became a recurring backdrop for many of his most famous works.

His favoured themes revolved around rural life and sporting pursuits. Hunting scenes, featuring pointers, setters, and hounds, were a staple of his output. Paintings like Grouse Shooting (1840) exemplify his early success in this genre. He also depicted pastoral scenes with shepherds, farmers, and their livestock, works such as A Galloway Farm (1841), Gathering the Sheep, and The Herd Lassie showcasing his empathy for the rhythms of agricultural life and the bond between humans and the land. His detailed studies of specific breeds, notably his work featuring Collies, are considered valuable artistic records for canine history.

Influences and Artistic Context: The Shadow of Landseer

No discussion of Victorian animal painting can ignore the towering figure of Sir Edwin Landseer. Landseer was the preeminent animal painter of the era, immensely popular with the public and royalty alike, known for his technical brilliance and often sentimental or anthropomorphic portrayals of animals. Richard Ansdell undoubtedly worked in Landseer's shadow and was influenced by his success and subject matter.

Comparisons between the two artists were common during their lifetimes and continue today. While both excelled in animal depiction, subtle but important distinctions exist. Landseer often aimed for greater dramatic effect and imbued his animal subjects with near-human emotions, sometimes bordering on the theatrical. Ansdell, while capable of depicting dramatic scenes, generally maintained a more grounded, observational approach. His focus often seemed more directed towards the accurate rendering of the animal within its natural or working environment, emphasizing realism and detailed finish over overt sentimentality. Critics sometimes noted Ansdell's finer, more detailed brushwork compared to Landseer's broader handling.

Beyond Landseer, Ansdell operated within a broader tradition of British animal and sporting art that included earlier masters like George Stubbs, renowned for his equine portraits, and George Morland, known for his rustic scenes. Ansdell absorbed these influences while developing his own distinct voice, one that balanced anatomical accuracy with picturesque composition and narrative interest, perfectly suited to the tastes of the Victorian era. His contemporary, Briton Rivière, also explored animal subjects, often with a more historical or symbolic leaning.

Collaboration and the Artistic Circle

Ansdell was not an isolated figure; he actively engaged with the artistic community of his time and participated in several notable collaborations. Working with other artists allowed him to combine his specialized skills in animal painting with the landscape or figure painting talents of his peers, resulting in works that showcased a broader range of expertise.

One of his most significant collaborators was the landscape painter Thomas Creswick. Creswick, also a Royal Academician, was known for his pleasing depictions of English and Welsh scenery. Together, they produced works where Creswick would typically paint the landscape setting, and Ansdell would add the animals and figures. Their joint painting titled England was lauded by critics as a "very successful instance of combined landscape and animal talent," demonstrating the fruitful synergy between their respective skills.

Ansdell also collaborated with William Powell Frith, a highly successful painter of modern-life genre scenes (famous for works like Derby Day and The Railway Station). Their joint efforts often focused on rural subjects, blending Frith's facility with figures and narrative with Ansdell's expertise in animal depiction. These collaborations further broadened Ansdell's reach and demonstrated his ability to work effectively within different artistic partnerships.

His connection with the Scottish painter John Phillip was also significant. Phillip, known for his vibrant scenes of Spanish life, travelled with Ansdell to Spain. It's suggested Ansdell may have received some early guidance or influence from Phillip, and their shared travels certainly impacted Ansdell's work. This network extended further; Ansdell was part of an informal sketching club known as the "Kensington Life Academy," which met at his studio. A key member of this group was Thomas Oldham Barlow, a highly regarded engraver who translated many popular paintings (including works by Ansdell, Landseer, and Phillip) into prints, making them accessible to a wider public.

Other contemporaries whose paths likely crossed Ansdell's at the Royal Academy exhibitions included figures like William Turner Davey. While the extent of direct interaction with every major figure like John Everett Millais or Frederic Leighton isn't fully documented in the provided sources, Ansdell was certainly a prominent and active member of the mid-Victorian London art world, interacting with many fellow Academicians and exhibitors like W.C. Smith from his early days. His work existed alongside that of earlier influential figures like George Stubbs and George Morland in the tradition of British animal art, and contemporaries like Briton Rivière.

Spanish Sojourns: New Light and Subjects

Seeking fresh inspiration and different subject matter, Richard Ansdell undertook journeys to Spain, notably in 1856 and 1857. He travelled at least once with his friend and fellow artist, John Phillip, whose own art was profoundly shaped by his experiences in Spain. These trips had a discernible impact on Ansdell's work, introducing new themes, brighter light, and different textures into his paintings.

The Spanish landscape, culture, and people offered a stark contrast to the familiar settings of the British Isles and the Scottish Highlands. Ansdell responded by creating a series of works reflecting his observations. Paintings such as The Water Carrier and The Spanish Shepherd depict everyday life and local character types. Mules Drinking, Seville captures a common scene with the same attention to animal detail he applied to British subjects, but bathed in the stronger Mediterranean sunlight.

These Spanish pictures often feature a brighter palette and a different atmospheric quality compared to his British scenes. While perhaps less numerous than his depictions of Scottish or English rural life, the Spanish works demonstrate Ansdell's willingness to explore new environments and broaden his artistic horizons. They add another dimension to his oeuvre, showcasing his versatility and his engagement with the wider European art scene, influenced by his travels alongside artists like John Phillip, whose daughter Mary Romer was also associated with these artistic circles.

Masterworks: Capturing Moments in Time

Throughout his long career, Richard Ansdell produced numerous paintings that became highly regarded and representative of his skill. Several stand out as key examples of his thematic interests and artistic prowess.

Grouse Shooting (1840): An early work exhibited at the Royal Academy, this painting helped establish Ansdell's reputation as a leading sporting artist. It likely depicted pointers or setters in action on the moors, capturing the tension and focus of the dogs and the atmosphere of the hunt, a theme popular with landowners and sportsmen.

A Galloway Farm (1841): This work exemplifies his interest in pastoral scenes and specific regional life. Galloway, in southwestern Scotland, is known for its distinctive cattle. The painting probably depicted the daily routines of farm life, showcasing livestock and figures within a carefully rendered landscape, highlighting the harmonious relationship between humans, animals, and their environment.

The Drover's Halt (An Incident in the Greate Cattle Drove from the Highlands to the Lowlands): Housed in the Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport, this significant work depicts the arduous journey of Highland cattle drovers. It captures a moment of rest for both men and beasts, conveying the challenges of moving livestock across vast distances. The painting is valued not only for its artistic merit but also as a historical document of a fading way of life in Scotland.

Gathering the Sheep and The Herd Lassie: These titles suggest quintessential Ansdell subjects, focusing on sheep farming in the Scottish Highlands. They likely feature shepherds, sheepdogs (perhaps his favoured Collies), and flocks of sheep set against dramatic Highland scenery, emphasizing the pastoral ideal and the skill involved in managing livestock in challenging terrain.

The Wounded Hound: This painting achieved significant recognition in the modern art market when it sold for a substantial sum (£478,000 in 2006), indicating the enduring appeal and value of Ansdell's work. The subject suggests a narrative moment, likely focusing on the aftermath of a hunt, allowing Ansdell to display his skill in depicting animal anatomy and conveying pathos.

Beyond the Pastoral: Social Commentary

While best known for his animal and rural scenes, Richard Ansdell occasionally tackled subjects with broader social or historical implications. One notable example is The Hunted Slaves, painted around 1861 or 1862. This powerful work diverges significantly from his usual subject matter.

Created during the American Civil War, the painting depicts two enslaved figures, presumably escapees, hiding from pursuit, possibly with bloodhounds nearby (a subject Ansdell, as an animal painter, could render with chilling accuracy). The work taps into the intense abolitionist sentiment prevalent in Britain at the time. By choosing this subject, Ansdell engaged with one of the most pressing moral and political issues of his day.

The Hunted Slaves demonstrates Ansdell's capacity to employ his realistic style for dramatic and socially conscious ends. It highlights the terror and desperation faced by those fleeing bondage, serving as a stark reminder of the human cost of slavery. While atypical within his overall output, this painting reveals a depth and engagement with contemporary events that adds another layer to his artistic identity, moving beyond the purely picturesque or sporting themes.

Acclaim, Recognition, and Later Years

Richard Ansdell enjoyed considerable success and recognition throughout his career. His consistent presence at the Royal Academy exhibitions, coupled with the popularity of his subjects among the Victorian public, ensured a steady stream of commissions and sales. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1861 and achieved the distinction of becoming a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1870.

His reputation extended beyond British shores. At the prestigious Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855, a major international showcase of arts and industry, Ansdell was awarded a silver medal (some sources mention gold, but silver appears more consistently cited) for his submissions. This international accolade further solidified his standing as a leading artist of his generation.

He continued to paint prolifically into his later years, maintaining his detailed style and focus on his favoured subjects. His work remained popular with collectors who appreciated his technical skill and the evocative portrayal of British rural life and sport. He resided for a time near Loch Lagan in the Scottish Highlands, immersing himself in the landscapes and life that so frequently inspired his art. Later, he lived at Collingwood Tower in Farnborough, Hampshire.

Personal Life, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Contrary to some accounts suggesting he remained unmarried, records indicate Richard Ansdell married a woman named Mary, and they had children, including two sons named Harry Blair Ansdell and Guy Leech Ansdell. This suggests a family life running parallel to his demanding artistic career.

Richard Ansdell passed away on April 20, 1885, at his home, Collingwood Tower, near Farnborough in Hampshire. He was laid to rest in Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey, a large Victorian cemetery that became the final resting place for many notable figures. He left behind a vast body of work that continues to be appreciated for its technical accomplishment and its evocative portrayal of a bygone era.

A unique aspect of his legacy is geographical. Ansdell is reportedly the only British artist to have an officially recognized district named after him. The area of Ansdell in Lytham St Annes, Lancashire, bears his name, a testament to his connection with the region and his considerable fame during his lifetime.

Today, Richard Ansdell's paintings are held in numerous public and private collections. Major institutions housing his work include the Tate Britain, the Royal Academy of Arts in London, National Museums Liverpool (Walker Art Gallery), and regional galleries like the Atkinson Art Gallery in Southport. The Lytham St Annes Art Collection holds a particularly significant number of his works, reportedly over twenty-five paintings. His art continues to appear at auction, often commanding high prices, demonstrating a sustained interest among collectors.

Conclusion: Ansdell's Place in British Art History

Richard Ansdell RA remains a key figure in 19th-century British art, particularly renowned for his mastery in depicting animals and scenes of rural and sporting life. His career spanned a significant portion of the Victorian era, and his work reflects many of the period's artistic tastes and preoccupations – a love for the countryside, an admiration for animals, and an appreciation for detailed realism and narrative clarity.

While perhaps overshadowed in popular memory by the more flamboyant Sir Edwin Landseer, Ansdell cultivated a distinct and highly respected artistic identity. His meticulous technique, his deep understanding of animal anatomy and behaviour, and his ability to capture the specific atmosphere of the British landscape, particularly the Scottish Highlands, earned him widespread acclaim and lasting recognition. Through collaborations with artists like Thomas Creswick and William Powell Frith, and his engagement with contemporaries via institutions like the Royal Academy and informal groups like the Kensington Life Academy, he was an active participant in the vibrant art world of his time. His journeys to Spain broadened his perspective, and occasional forays into social commentary, like The Hunted Slaves, revealed further dimensions to his talent. Richard Ansdell's legacy endures in his numerous paintings, which continue to offer compelling visions of Victorian Britain's relationship with the natural world.