Richard Westall stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of British art during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. A contemporary of giants like J.M.W. Turner and Thomas Girtin, Westall carved his own distinct path as a painter, primarily in watercolour but also in oils, and as one of the most prolific and sought-after book illustrators of the Romantic era. Elected a Royal Academician and appointed drawing master to the future Queen Victoria, his career reflects both considerable success and the shifting tastes of the time. His work, characterized by its technical finesse, dramatic intensity, and engagement with literary and historical themes, offers a valuable window into the artistic sensibilities of his age.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Richard Westall was born in Hertford in 1765, although his family had connections with Norwich, a city known for its own burgeoning school of painters. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him away from a potentially different path. Instead of pursuing a more conventional trade, he was apprenticed around 1779 to John Thompson, a respected heraldic engraver on silver in Gutter Lane, London. This training, focused on precision and line, likely provided a foundational discipline, but Westall's ambitions lay in the realm of fine art.

His desire to become a painter led him to seek formal instruction. In 1785, he took the crucial step of enrolling as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools. This institution was the epicentre of artistic training and exhibition in Britain, presided over at the time by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and later Benjamin West. Here, Westall would have honed his skills in drawing from casts and the life model, absorbing the principles of academic art theory while being exposed to the work of established and emerging artists.

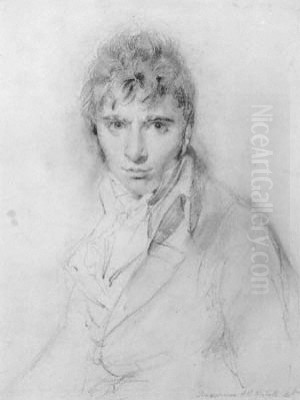

During these formative years, Westall formed a close and significant friendship with another aspiring artist, Thomas Lawrence. Lawrence, who would later become Sir Thomas Lawrence and President of the Royal Academy, shared lodgings with Westall for a period. This proximity fostered mutual influence and support. Lawrence recognized Westall's talent early on, a testament to the latter's burgeoning capabilities even as a student. This period at the RA Schools laid the essential groundwork for Westall's professional career, immersing him in the competitive yet stimulating London art world.

Ascent at the Royal Academy

Westall's talent did not go unnoticed for long. He began exhibiting at the Royal Academy as early as 1784, even before officially enrolling as a student, signaling his ambition and confidence. His submissions quickly garnered positive attention, showcasing his skill in historical and literary subjects, often rendered with a dramatic flair that resonated with the developing Romantic taste. His progress within the Academy's hierarchy was notably swift, reflecting the high regard in which his work was held by his peers.

In November 1792, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This was a significant step, marking him as an artist of considerable promise and granting him partial privileges within the institution. Just two years later, in February 1794, he achieved the highest rank, being elected a full Royal Academician (RA). This rapid ascent, achieved before the age of thirty, was remarkable and placed him among the elite of the British art establishment, alongside figures like Henry Fuseli, James Northcote, and John Opie.

Membership in the Royal Academy was more than just an honour; it provided crucial exhibition opportunities at the annual Summer Exhibition, enhanced professional standing, and facilitated connections with patrons and fellow artists. Westall became a regular and prolific contributor to the RA exhibitions for decades, showcasing a wide range of subjects, from intimate watercolours to large-scale historical oil paintings. His presence at the Academy solidified his reputation as a leading artist of his generation.

Pioneer of Watercolour Technique

While proficient in oils, Richard Westall made arguably his most significant contribution in the medium of watercolour. He was at the forefront of a movement that sought to elevate watercolour from its traditional role in topographical depiction or preparatory sketching to a medium capable of rivaling oil painting in richness, depth, and finish. This ambition was shared by contemporaries like Thomas Girtin and J.M.W. Turner, though Westall pursued it with his own distinct style and emphasis.

Unlike the earlier generation of watercolourists, such as Paul Sandby, who often used transparent washes over linear drawing, Westall employed more complex techniques. He utilized opaque bodycolour (gouache) alongside transparent washes, built up layers of colour to achieve depth and luminosity, and sometimes incorporated techniques like scratching out highlights or using gum arabic to enrich dark tones and add gloss. His aim was often to create highly finished, easel-worthy pictures that could hold their own in exhibition settings.

His watercolours are characterized by their often jewel-like colours, sophisticated handling of light and shadow, and meticulous detail. He demonstrated that watercolour could effectively convey dramatic narratives, complex compositions, and intense emotion. Some contemporary accounts even suggested that in achieving a certain kind of highly wrought finish and richness in watercolour, Westall initially surpassed even Turner and Girtin, though their later innovations would ultimately prove more revolutionary. Nonetheless, Westall's technical mastery significantly advanced the status and potential of the watercolour medium in Britain.

Historical and Literary Narratives

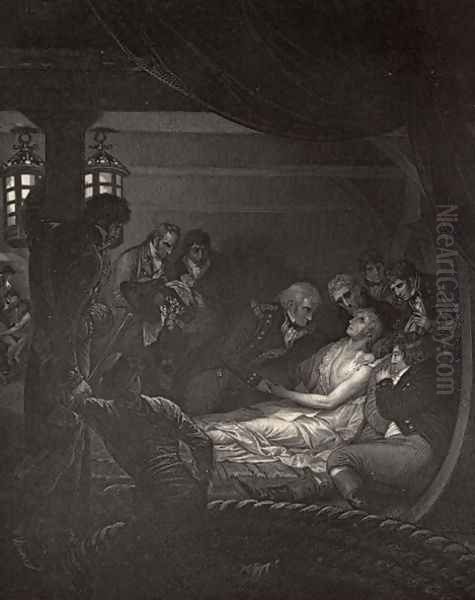

The core of Westall's subject matter lay in historical, biblical, and literary themes, reflecting the prevailing tastes of the Neoclassical and Romantic periods. He possessed a strong narrative sense, often choosing moments of high drama, pathos, or moral significance. His academic training provided him with the skills to handle complex multi-figure compositions, drawing upon classical and Renaissance models, but infused with the heightened emotion and dynamism characteristic of Romanticism.

Biblical scenes offered fertile ground for his dramatic imagination. Works like Isaac Blessing Jacob demonstrate his ability to convey familial tension and divine significance through gesture and expression. The Last Judgement, another subject he tackled, allowed for the depiction of sublime power and awe, using strong contrasts of light and dark (chiaroscuro) and dynamic arrangements of figures to create a sense of overwhelming scale and divine intervention. These works aligned with the Romantic fascination with the supernatural, the epic, and the emotionally charged.

History painting, considered the highest genre in academic theory, was also a significant part of his output. Mary Queen of Scots going to her Execution is a prime example, capturing a moment of tragic dignity and historical weight. He frequently drew inspiration from British history and classical antiquity. His literary subjects were equally important, drawing heavily from the giants of English literature, particularly Shakespeare and Milton, whose works provided ample scope for dramatic and imaginative interpretation. Westall's ability to translate these revered texts into compelling visual narratives was central to his success.

A Prolific Illustrator

Beyond his exhibition paintings, Richard Westall established himself as one of the most successful and sought-after book illustrators of his time. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw a boom in illustrated book publishing, catering to a growing literate public eager for visually enhanced editions of classic and contemporary texts. Westall's style – elegant, dramatic, and technically refined – proved perfectly suited to this market.

He received numerous commissions from leading publishers, including John Sharpe and, notably, John Boydell for his ambitious Shakespeare Gallery project. Boydell aimed to foster a British school of history painting by commissioning leading artists, including Westall, Fuseli, Northcote, Opie, and others, to paint scenes from Shakespeare's plays, which were then engraved and published. Westall contributed several works to this influential, though ultimately financially troubled, venture, illustrating scenes from plays like Hamlet and Macbeth.

His illustrations graced editions of John Milton's Paradise Lost, the Bible, Oliver Goldsmith's poems, Thomas Gray's Poems, James Thomson's The Seasons, Sir Walter Scott's narrative poems like Marmion, and Cervantes' Don Quixote. His designs, translated into engravings by skilled craftsmen, reached a wide audience, shaping the popular visual understanding of these literary works. Westall's success in this field provided a steady income stream and significantly enhanced his public profile, making his name familiar in households across Britain. His illustrations are often characterized by graceful figures, clear storytelling, and an ability to capture the emotional tone of the text.

Portraiture and Society

While primarily known for historical and literary subjects, Westall was also an accomplished portraitist. His portraits often display a sensitivity and elegance that appealed to his sitters. His most famous portrait is undoubtedly that of George Gordon, Lord Byron, the celebrated Romantic poet. Commissioned probably around 1813 by Byron's publisher, John Murray, this depiction became one of the defining images of the poet. It captures Byron's brooding good looks and charismatic intensity, perfectly aligning with the public persona of the quintessential Romantic hero. The portrait, now housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London, remains an iconic image in literary history.

The circumstances surrounding the Byron portrait and Westall's simultaneous commissions to illustrate the poet's works may have led to some professional complexities or "confusion," as hinted at in some accounts, perhaps relating to copyright, reproduction rights, or the sheer demand for images of the famous poet. Westall's ability to capture a likeness while imbuing it with a sense of character and contemporary sensibility made him a capable portrait painter, even if it wasn't his primary focus.

His skills in portraiture also played a role in his later royal connection. He painted other society figures and literary personalities, contributing to the visual record of the era. His portrait style often blended accuracy with a degree of idealization, consistent with the conventions of the time but rendered with his characteristic refinement.

Royal Patronage and Teaching

A significant mark of Westall's standing came later in his career with his connection to the British monarchy. In 1827, he was appointed drawing master to the young Princess Victoria of Kent, the heir presumptive to the throne. This prestigious appointment involved instructing the future queen in the art of drawing and watercolour painting, skills considered essential for a well-educated lady of her rank. He held this position until his death.

This role brought him into the royal circle and provided a degree of financial security, although, as events would show, it did not ultimately shield him from hardship. His relationship with his royal pupil appears to have been cordial. An anecdote survives from 1836, the year of Westall's death: the Princess, recovering from illness, wrote to Westall expressing a wish that he might paint her portrait. Westall eagerly seized the opportunity, hoping perhaps for a final prestigious commission, but sadly, he died before the portrait could be completed or possibly even properly started. This royal connection underscores the respect Westall commanded as an artist and instructor, even late in his life.

Artistic Circle and Collaborations

Throughout his career, Westall moved within the vibrant London art world, interacting with numerous fellow artists, patrons, and publishers. His early close friendship and shared lodgings with Thomas Lawrence remained a significant connection, linking him to one of the era's most successful portraitists and future leader of the Royal Academy. While their artistic paths diverged, the mutual respect likely endured.

His participation in Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery brought him into collaboration, or at least shared enterprise, with many leading painters of the day, fostering a sense of collective effort in promoting British art. His relationship with William Blake is less documented in terms of personal interaction, but they were contemporaries at the RA Schools and both navigated the worlds of painting and illustration, albeit with vastly different artistic visions and career trajectories. Blake's mystical symbolism contrasts sharply with Westall's more accessible Romantic classicism.

A particularly important familial connection was with his younger half-brother, William Westall (1781-1850). William also trained at the RA Schools and became a noted landscape painter and draughtsman. Significantly, William served as the official landscape artist on Matthew Flinders' renowned expedition to circumnavigate Australia aboard HMS Investigator (1801-1803). Richard's established position likely aided William's early career. Richard also maintained connections with literary figures, such as the poet John Ayton, with whom he corresponded and whose portrait he painted. The diary of fellow RA member Joseph Farington provides glimpses into the social and professional life of artists like Westall during this period, revealing a world of exhibitions, commissions, rivalries, and collaborations.

Later Years and Financial Difficulties

Despite his considerable achievements, Royal Academy membership, and royal appointment, Richard Westall's later years were marked by financial insecurity. The art market could be fickle, and tastes began to shift. While his illustrations continued to be popular, income from large-scale paintings may have become less reliable. Furthermore, investments or financial management might have played a role in his difficulties.

Sources suggest that Westall invested poorly, particularly in Old Master paintings, and suffered losses. The changing artistic landscape, with the rise of different styles and younger artists, might also have impacted the demand for his specific brand of historical and literary painting. Even his position as drawing master to Princess Victoria did not guarantee lasting prosperity.

He continued to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy and the British Institution until the end of his life. However, when Richard Westall died on December 4, 1836, at the age of 71, he was reportedly in significant financial distress. His death occurred just months before his royal pupil, Victoria, ascended the throne. His collection of pictures and drawings was sold posthumously to settle debts, a somewhat poignant end for an artist who had enjoyed considerable fame and recognition for much of his career.

Legacy and Critical Reception

Richard Westall's legacy is multifaceted. In his lifetime, he was highly regarded for his technical skill, particularly in watercolour, and his ability to create elegant and dramatic compositions. His election to the Royal Academy at a young age and his long exhibiting career attest to his standing among his peers. Figures like Thomas Lawrence held his talents in high esteem. His contribution to the elevation of watercolour as a serious exhibition medium was significant, demonstrating its potential for richness and finish.

His book illustrations were immensely influential, shaping the visual imagination of generations of readers and setting a high standard for commercial illustration. Works like his Byron portrait became defining images. However, after his death, his reputation gradually declined. The dramatic, sometimes theatrical, quality of his historical and literary works perhaps fell out of favour with the rise of Victorian realism and later modernist movements. For much of the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries, he was often overshadowed by contemporaries perceived as more innovative, like Turner, Girtin, or Blake.

In recent decades, however, there has been a renewed scholarly interest in Westall and his era. Art historians now recognize his importance within the context of British Romanticism, his technical prowess in watercolour, and his significant role in the history of book illustration. While perhaps not possessing the revolutionary vision of Turner or the unique mysticism of Blake, Westall is acknowledged as a highly skilled, versatile, and influential artist who successfully navigated the demands of the art market and contributed significantly to the visual culture of his time. His works are held in major collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, and the Royal Academy itself, ensuring his contribution is not forgotten.

Conclusion

Richard Westall RA occupies a vital place in the narrative of British art during a period of significant transition and artistic ferment. As a master watercolourist, he pushed the boundaries of the medium, striving for a richness and complexity that rivaled oil painting. As a painter of historical, biblical, and literary scenes, he captured the dramatic and emotional spirit of the Romantic era with elegance and technical skill. His prolific work as a book illustrator brought art into the homes of many, visually interpreting the canonical texts of his day. Though his fame waned after his death, and he faced financial hardship in his later years, his election as a Royal Academician, his role as tutor to a future queen, and the enduring appeal of works like his Byron portrait testify to the considerable success he achieved. Richard Westall remains a key figure for understanding the diverse artistic landscape of British Romanticism.