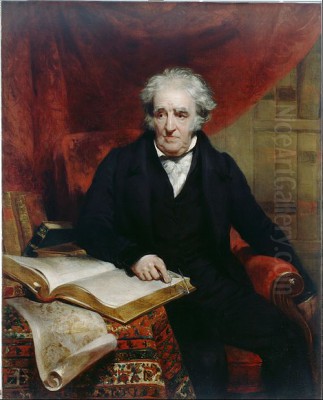

Thomas Stothard RA (17 August 1755 – 27 April 1834) stands as a significant, if sometimes underestimated, figure in the landscape of British art during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. A prolific painter, illustrator, and designer, Stothard's career spanned a period of profound artistic and social change, witnessing the transition from Neoclassicism to the burgeoning Romantic movement. His work, characterized by its grace, charm, and narrative clarity, found expression across a remarkable range of media, from grand oil paintings and ambitious decorative schemes to the intimate scale of book illustrations, for which he became particularly renowned. His ability to capture the spirit of literary texts and translate them into compelling visual forms made him one of the most sought-after illustrators of his day, leaving an indelible mark on the visual culture of Britain.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Thomas Stothard was born in Long Acre, London, on August 17, 1755. His father, also named Thomas, was a prosperous innkeeper of the Black Horse in Long Acre. This comfortable, though not aristocratic, background provided a stable environment for the young Stothard. He was not initially destined for a career in the arts. Due to delicate health in his early years, he was sent to live with relatives in Yorkshire. There, at Acomb, he attended a village school and later, from the age of eight to thirteen, was a boarder at a school in Stutton-in-the-Forest, near Tadcaster.

During his time in Yorkshire, Stothard began to show a proclivity for drawing, often sketching from nature and copying any prints he could find. His early artistic inclinations were noted, but his formal path into the arts was somewhat indirect. Upon returning to London around the age of thirteen, following his father's death, he was apprenticed in 1770 to John Vansommer, a draughtsman of patterns for brocaded silks in Spitalfields. This apprenticeship, though focused on commercial design, undoubtedly honed his skills in draughtsmanship, precision, and decorative composition – qualities that would later inform his illustrative work.

The silk trade, however, was experiencing a downturn, and Vansommer's business suffered. More significantly for Stothard's future, his master passed away. This event, coupled with his growing passion for more pictorial forms of art, led Stothard to dedicate himself more fully to drawing and painting. During his leisure hours as an apprentice, he had already begun to create illustrations for his favorite literary works, particularly those of the poets. These early efforts demonstrated a natural talent for narrative and characterization.

Entry into the Royal Academy and Early Career

Stothard's burgeoning talent did not go unnoticed. His illustrations, particularly those for the works of poets like Ossian, came to the attention of James Harrison, the editor of the Novelist's Magazine. Harrison was impressed by the young artist's abilities and commissioned him to produce designs for the publication. This was a pivotal moment, providing Stothard with regular employment and public exposure. His work for the Novelist's Magazine would eventually number 148 designs, showcasing his versatility in interpreting a wide array of literary styles and subjects.

Seeking to formalize his artistic education and elevate his standing, Stothard enrolled as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools on August 21, 1778. The Royal Academy, founded a decade earlier under the patronage of King George III with Sir Joshua Reynolds as its first president, was the epicentre of the British art world. Here, Stothard would have been exposed to the prevailing Neoclassical ideals, the study of antique sculpture, and the principles of academic drawing and painting. He would have also encountered fellow students and established academicians, including figures like Benjamin West, who succeeded Reynolds as president, and the Swiss-born Henry Fuseli, known for his dramatic and often unsettling subjects.

Stothard's progress at the Academy was steady. He began exhibiting there in 1778, the same year he became a student. His talent and diligence were recognized, and he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) on November 10, 1791. Just a few years later, on February 10, 1794, he achieved the distinction of being elected a full Royal Academician (RA), a testament to his established reputation. His commitment to the institution continued; he served as Assistant Librarian from 1810 to 1812, and then as Librarian from 1812 until his death, succeeding Fuseli in that role.

The Illustrator Par Excellence

While Stothard was a capable painter in oils, it was as an illustrator that he truly excelled and achieved widespread fame. His output in this field was prodigious, encompassing a vast range of literary works, from epic poems and classic novels to contemporary poetry and popular periodicals. His illustrations were admired for their elegance, delicacy, and sympathetic understanding of the text. He possessed a remarkable ability to convey narrative, emotion, and character with a graceful line and harmonious composition.

His early work for Harrison's Novelist's Magazine and Bell's Poets of Great Britain established his reputation. He provided illustrations for editions of Samuel Richardson's Pamela and Clarissa, Henry Fielding's Joseph Andrews and Tom Jones, and Tobias Smollett's novels. These works required him to depict scenes of contemporary life, domestic drama, and comic incident, all of which he handled with aplomb.

Stothard's interpretations of Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe were particularly popular and influential. He produced several sets of illustrations for Defoe's classic, emphasizing themes of human ingenuity, perseverance, and the relationship between man and nature. His Crusoe is often depicted as a resourceful and dignified figure, and his illustrations contributed to the enduring visual iconography of the character. Similarly, his designs for John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress and Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield became standard visual accompaniments to these beloved texts.

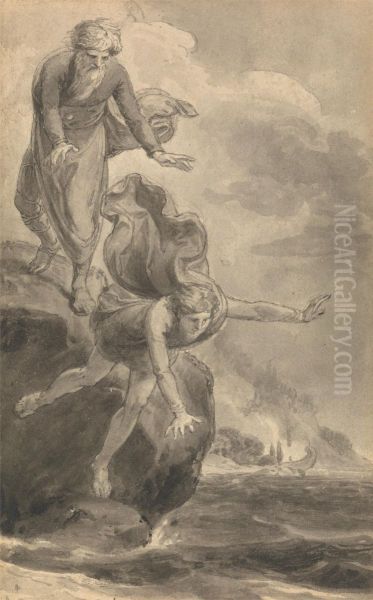

He also ventured into more epic and classical territory. His illustrations for editions of Homer's Iliad and Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene demonstrated his ability to handle grander themes and more fantastical subjects. In these, one can see an affinity with the emerging Romantic sensibility, with an emphasis on heroism, chivalry, and the sublime. His illustrations for Milton's L'Allegro and Il Penseroso captured the contrasting moods of these lyrical poems with sensitivity.

The sheer volume of Stothard's illustrative work is staggering. He designed plates for John Boydell's ambitious Shakespeare Gallery project, though his contributions were perhaps overshadowed by more dramatic artists like Fuseli or James Northcote. He also created illustrations for Rogers's Poems and Italy, which were highly praised for their refined beauty and were engraved with exquisite skill by engravers such as Luke Clennell, James Heath, and Francesco Bartolozzi, the latter being a highly influential engraver and founding member of the Royal Academy. The collaboration between Stothard and his engravers was crucial, as the engraver's skill determined the final quality of the printed image.

His designs were not limited to books. He produced illustrations for almanacs, pocket-books, and even concert tickets. These smaller, ephemeral works often possess the same charm and elegance as his more ambitious book illustrations and were eagerly sought by collectors.

Mastery in Oils and Decorative Arts

Although primarily celebrated for his illustrations, Thomas Stothard was also a painter in oils, producing historical subjects, genre scenes, and literary themes. His oil paintings are generally characterized by their rich, bright, and harmonious colouring, often showing an influence from Flemish masters like Peter Paul Rubens, particularly in their warmth and vibrancy. While perhaps lacking the dramatic intensity of some of his contemporaries, his paintings possess a gentle, lyrical quality.

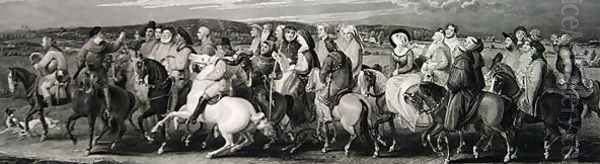

One of his most famous oil paintings is The Procession of the Canterbury Pilgrims, a frieze-like composition depicting Chaucer's diverse cast of characters on their journey. This work, painted between 1806 and 1807, is now in the Tate Britain collection. It showcases Stothard's skill in characterization and his ability to manage a complex, multi-figure composition. The subject itself, drawn from a cornerstone of English literature, was a popular one, and Stothard's interpretation was widely admired for its historical detail and lively portrayal of the pilgrims.

Another significant oil painting is The Vintage, sometimes referred to as The Fine, held by the National Gallery, London. This work, with its classical allusions and joyful depiction of a bacchanalian scene, again demonstrates his debt to Old Masters and his skill in creating harmonious, flowing compositions. His mythological and allegorical subjects, such as Diana and Her Nymphs Bathing or Nymphs Binding Cupid, often possess a Rococo charm blended with a more Romantic sensibility.

Stothard's versatility extended to large-scale decorative projects. He designed the magnificent grand staircase at Burghley House, Northamptonshire, with scenes depicting "War," "Peace," and "Intemperance." This ambitious project, undertaken for the Marquess of Exeter, allowed him to work on a monumental scale. He also painted the ceiling of the Advocates' Library in Edinburgh (now part of the National Library of Scotland) and designed decorative friezes for Buckingham Palace, notably for the Throne Room, though some of these were executed after his death or not fully realized as per his original intentions. These commissions indicate the high regard in

which his decorative abilities were held.

He also designed the Wellington Shield, a monumental piece of silverwork presented to the Duke of Wellington by the merchants and bankers of London. Stothard's designs for this piece, depicting Wellington's victories, were translated into relief by skilled silversmiths, showcasing his adaptability to different media and his capacity for grand, commemorative design.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Romantic Sensibilities

Thomas Stothard's artistic style is often described as graceful, elegant, and charming. His figures are typically slender and idealized, moving with a gentle, rhythmic quality. His compositions are carefully balanced and harmonious, often avoiding dramatic extremes of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in favor of a more even, luminous quality. His colour palette in his oil paintings is rich and warm, while his watercolours and drawings display a delicate touch and subtle tonal gradations.

While he received academic training at the Royal Academy, and his early work shows Neoclassical influences in its clarity and order, Stothard's art increasingly aligned with the burgeoning Romantic movement. This is evident in his choice of literary subjects, often drawn from medieval romance, Shakespeare, Milton, and contemporary poets who emphasized emotion, imagination, and the beauty of nature. His illustrations for Robinson Crusoe, for instance, often depict a more idealized and harmonious relationship between Crusoe and his island environment than Defoe's text might suggest, reflecting a Romantic appreciation for nature.

He was certainly aware of the work of earlier masters. The influence of Raphael can be seen in the grace and harmony of his figures, while, as mentioned, Rubens seems to have inspired his warm colouring and dynamic compositions in some oil paintings. He also admired the work of 16th-century Italian Mannerists like Parmigianino for their elongated, elegant figures, a quality sometimes reflected in his own work. However, Stothard synthesized these influences into a distinctly personal style that was well-suited to the tastes of his time.

His approach to literary illustration was interpretative rather than strictly literal. He sought to capture the spirit and mood of the text, often imbuing his scenes with a gentle sentimentality or a quiet heroism. In some of his illustrations, particularly for classical texts like the Iliad, there's an attempt to highlight the roles and emotions of female characters, suggesting a sensitivity that could be seen as an early exploration of themes that later feminist critics might appreciate.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and the Blake Controversy

Stothard operated within a vibrant London art world. He was a contemporary of major figures such as Sir Thomas Lawrence, the leading portrait painter of the Regency era and later President of the Royal Academy, and J.M.W. Turner, the revolutionary landscape painter. While Stothard's style was gentler and less radical than Turner's, both artists contributed significantly to the Romantic movement in Britain. He also knew John Constable, another giant of landscape painting.

He was closely associated with the sculptor John Flaxman, whose Neoclassical designs, particularly his outline illustrations for Homer and Dante, shared a certain purity of line with Stothard's work, though Flaxman's style was generally more austere. Both Stothard and Flaxman, along with William Blake, are sometimes grouped together as artists who explored visionary and literary themes, though their individual styles and temperaments differed significantly.

The relationship between Thomas Stothard and William Blake is one of the most discussed aspects of Stothard's career, primarily due to a significant controversy surrounding an illustration of Chaucer's Canterbury Pilgrims. Both artists produced a painting and an engraving of this subject around the same time. Blake had shown his initial design to the publisher Robert Cromek, who then, according to Blake, commissioned Stothard to paint a similar subject without Blake's knowledge, effectively stealing his idea. Cromek and Stothard, however, maintained that Stothard had conceived of the idea independently or that Cromek had commissioned Stothard first.

Blake felt deeply betrayed and publicly accused Stothard and Cromek of plagiarism in his Descriptive Catalogue for his 1809 exhibition, which included his own version of the Canterbury Pilgrims. He wrote scathingly of Stothard's version, contrasting its perceived weaknesses with the spiritual and artistic integrity he claimed for his own. This public feud caused a rift between the two artists, who had previously been on friendly terms. Stothard's version, engraved by Louis Schiavonetti and later by James Heath, proved to be commercially more successful, which likely added to Blake's bitterness. Art historians continue to debate the precise sequence of events and the ethics involved, but the incident highlights the competitive nature of the art market and the passionate convictions of artists like Blake. Despite this unfortunate episode, Stothard was generally known for his amiable and gentle disposition.

Stothard was also part of what is sometimes loosely termed the "Blake School" or circle, which included younger artists influenced by Blake's visionary art, such as Samuel Palmer and George Richmond. While Stothard's own art was less mystical than Blake's, his engagement with literary and imaginative themes placed him within this broader current of Romanticism.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Thomas Stothard remained active and productive throughout his long career. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy and fulfill commissions for illustrations and paintings. His position as Librarian of the Royal Academy provided him with a steady income and kept him at the heart of the institution.

He married Rebecca Watkins in 1783, and they had several children. His son, Charles Alfred Stothard, became a talented antiquarian draughtsman but tragically died young in an accident. Another son, Alfred Joseph Stothard, became a medallist. The loss of Charles was a severe blow to the elder Stothard.

Thomas Stothard died at his home at 28 Newman Street, London, on April 27, 1834, at the age of 78. He was buried in Bunhill Fields, the same Dissenters' burial ground where William Blake and Daniel Defoe, among other notable figures, were interred.

Stothard's legacy is primarily that of a master illustrator whose work defined the visual interpretation of countless literary classics for generations of readers. His graceful style, narrative clarity, and sympathetic understanding of character made his illustrations immensely popular and influential. While the taste for his particular brand of gentle Romanticism waned somewhat in the later 19th century with the rise of more robust or Pre-Raphaelite aesthetics (artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti or John Everett Millais offered very different illustrative styles), his contribution to the history of British art and book illustration remains significant.

His oil paintings, though less numerous and perhaps less impactful than his graphic work, demonstrate his skill as a colourist and composer. Works like The Procession of the Canterbury Pilgrims hold an important place in the tradition of British narrative painting. His decorative designs for Burghley House and Buckingham Palace attest to his versatility and his ability to work on a grand scale.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, there has been a renewed appreciation for Stothard's art, particularly his illustrations. Scholars and collectors recognize the quality and charm of his work, and his influence on the development of book illustration is acknowledged. He successfully bridged the gap between the elegance of the 18th century and the burgeoning emotionalism of the Romantic era, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically pleasing. His ability to connect with a wide audience through accessible and engaging imagery ensured his place as a beloved artist of his time, and his prolific output continues to offer rich material for study and enjoyment. He may not have possessed the revolutionary genius of a Blake or a Turner, or the society portraiture finesse of a Thomas Gainsborough or Reynolds, but in his chosen fields, particularly illustration, Thomas Stothard was a master whose quiet artistry enriched the cultural life of Britain.