Alfred Edward Chalon, a name synonymous with the elegance and burgeoning cultural confidence of 19th-century Britain, remains a significant figure in the annals of art history. Though Swiss by birth, his artistic identity was forged in England, where he rose to prominence as a favoured portraitist of the societal elite, including the young Queen Victoria herself. His mastery of watercolour, his keen eye for character, and his ability to capture the fashionable zeitgeist of his era cemented his reputation. This exploration delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist who skillfully navigated the dynamic art world of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Alfred Edward Chalon was born in Geneva, Switzerland, on February 15, 1780. His family background was one of intellectual pursuit; his father, Jean Chalon, was a man of letters who later secured a position as a professor of French at the prestigious Royal Military College at Sandhurst upon the family's relocation to England. This move proved pivotal for young Alfred, immersing him in the vibrant artistic and cultural milieu of London at a young age. The British capital, then a global centre of art and commerce, offered unparalleled opportunities for aspiring artists.

The artistic inclination was strong within the Chalon family. Alfred's elder brother, John James Chalon (1778-1854), also pursued a career as a painter, primarily known for his landscapes and genre scenes. The brothers would maintain a close personal and professional relationship throughout their lives, often exhibiting together and sharing a household in their later years. This familial support and shared artistic passion undoubtedly played a role in Alfred's early development.

In 1797, at the age of seventeen, Alfred Edward Chalon took a decisive step towards a formal artistic career by enrolling in the Royal Academy Schools. The Royal Academy of Arts, founded by luminaries such as Sir Joshua Reynolds and Sir William Chambers, was the preeminent institution for artistic training in Britain. Here, Chalon would have received a rigorous academic grounding, studying from antique casts, life models, and the works of Old Masters. This period was crucial for honing his draughtsmanship and understanding of composition, skills that would become hallmarks of his later portraiture.

Ascent within the Royal Academy and Artistic Circles

Chalon's talent did not go unnoticed for long. He began exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1810, and his skillful and appealing works quickly garnered positive attention. His progress within the academic hierarchy was steady: he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1812, a significant recognition of his growing stature. Just four years later, in 1816, he achieved the distinction of becoming a full Royal Academician (RA), a coveted honour that placed him among the leading artists of the nation.

Beyond his individual achievements, Chalon was an active participant in the artistic community. He, along with his brother John James, was instrumental in founding "The Evening Sketching Society" (sometimes referred to simply as "The Sketching Society"). This informal but influential group of artists met regularly to sketch subjects from poetry and history, fostering a spirit of camaraderie, friendly competition, and creative exploration. Such societies were common in the period, providing artists with a forum to experiment outside the more formal constraints of commissioned work and public exhibitions. The Evening Sketching Society, which reportedly continued for some forty years, included other notable artists and contributed to the rich tapestry of London's art life. Figures like Charles Robert Leslie and Clarkson Stanfield were also associated with similar sketching societies, highlighting the importance of these informal networks.

Chalon's primary medium, especially for his celebrated portraits, was watercolour. While oil painting held a higher status in the academic hierarchy of the time, watercolour painting was experiencing a golden age in Britain, with artists like J.M.W. Turner, John Sell Cotman, Peter De Wint, and David Cox elevating the medium to new heights of expressiveness and technical brilliance. Chalon carved a distinct niche for himself within this tradition, focusing on the human figure and, particularly, on elegant portraiture.

Artistic Style: Elegance, Individuality, and Thematic Diversity

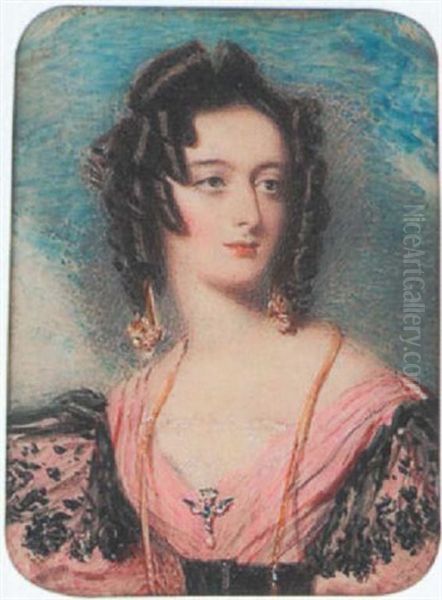

Alfred Edward Chalon's artistic style is characterized by its vivacity, elegance, and an acute sensitivity to the personality and social standing of his sitters. He was particularly adept at capturing the likenesses of women, rendering the textures of luxurious fabrics – silks, satins, and lace – with a delicate and assured touch. His female portraits often exude a fashionable charm, reflecting the romantic sensibilities of the era. However, his work was not merely about superficial allure; he possessed a talent for imbuing his subjects with a sense of individuality and inner life.

His portraits, typically around fifteen inches in height, were praised for their fluid lines and the absence of tired artistic conventions or clichés. He sought to present his sitters in a manner that was both flattering and authentic. This approach resonated with the tastes of London's high society, who sought portraits that were both sophisticated and reflective of their status.

While portraiture formed the bedrock of his fame and income, Chalon's artistic interests were broader. He also painted subject pictures, often drawing inspiration from history, literature (especially Shakespeare and Sir Walter Scott), and mythology. These works allowed him to explore more complex compositions and narrative themes. His style could adapt to these different genres, sometimes showing a more robust and dramatic handling, particularly in his historical pieces. He was also known to create caricatures and humorous subjects, demonstrating a lighter, more playful side to his artistic persona.

Chalon was not an isolated figure stylistically. He was aware of, and sometimes emulated, the styles of other artists. For instance, he was known to admire and occasionally imitate the Rococo charm of French masters like Jean-Antoine Watteau and Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose influence can be discerned in the graceful poses and delicate handling of some of his figures. This ability to absorb and adapt different stylistic elements, while retaining his own distinctive voice, contributed to the versatility of his output. He also produced oil paintings, though he is predominantly remembered for his mastery in watercolour.

Royal Patronage and Widespread Recognition

A pivotal moment in Alfred Edward Chalon's career came with the accession of Queen Victoria to the throne in 1837. The young queen, a keen patron of the arts, quickly developed an appreciation for Chalon's work. He was chosen to paint a portrait of Victoria, which was commissioned by her mother, the Duchess of Kent, as a gift to the Queen. This particular portrait depicted the Queen in her State Robes, on the occasion of her first official act: going to the House of Lords to prorogue Parliament in July 1837.

This painting achieved iconic status. It was engraved by Samuel Cousins in 1838, and prints were widely distributed, making Chalon's image of the Queen familiar to a vast public. The portrait was so well-received that it led to Chalon's formal appointment as "Portrait Painter in Water-Colours to Her Majesty." This royal endorsement significantly enhanced his prestige and desirability as a portraitist among the aristocracy and the wealthy.

The impact of this royal portrait extended even further. From 1851, an adaptation of Chalon's depiction of Queen Victoria, known as the "Chalon Head," began to appear on postage stamps in several British colonies, including the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, New Zealand, and Queensland, among others. This widespread use of his image on official government documents further solidified his fame, not just in Britain but across the burgeoning British Empire. The "Chalon Head" stamps are now highly prized by philatelists and serve as a unique testament to the artist's reach.

While Chalon enjoyed Queen Victoria's favour, he was not her only preferred artist. The German painter Franz Xaver Winterhalter also became a dominant force in royal portraiture, particularly for large-scale oil paintings. However, Chalon's specialty in watercolour and his distinct, less formal style ensured his continued importance. Other prominent portraitists of the era included Sir Thomas Lawrence (who died in 1830 but whose influence lingered), Sir Francis Grant, and George Hayter, each contributing to the rich landscape of Victorian portraiture.

Notable Works: A Glimpse into Chalon's Oeuvre

Alfred Edward Chalon was a prolific artist, and many of his works were exhibited at the Royal Academy and other institutions. Among his extensive body of work, several pieces stand out either for their artistic merit, their subject matter, or their historical significance.

One of his most famous works is, of course, the aforementioned Portrait of Queen Victoria in her State Robes (c. 1837). This image, often referred to by various titles related to her first appearance in Parliament or her coronation attire, captured the youth and regal bearing of the new monarch. Its dissemination through engravings made it one of the defining images of the early Victorian period.

John Knox reproving the Ladies of Queen Mary's Court (1837) showcases Chalon's engagement with historical subjects. This work depicts a dramatic confrontation between the stern Scottish reformer John Knox and the more worldly attendants of Mary, Queen of Scots. Such historical genre scenes were popular in the 19th century, appealing to a public interested in national history and moral narratives. Artists like Daniel Maclise and Charles Robert Leslie also excelled in this genre.

Hunt the Slippers (1831) is an example of Chalon's lighter, more playful genre scenes. Depicting a popular parlour game, this work captures a moment of domestic amusement and social interaction. It reflects an interest in everyday life and the charm of informal gatherings, a theme also explored by contemporaries like William Powell Frith, though Frith's canvases were often on a much grander scale, depicting panoramic views of modern life.

Morning Walk, Samson and Delphine (1837) indicates his interest in biblical or mythological themes, often infused with a romantic sensibility. The title suggests a narrative moment, allowing Chalon to explore character and emotion through the depiction of these legendary figures.

Serena (1847), Seasons (1851), and Sophia Western (1857) are titles that suggest allegorical subjects or portraits inspired by literary characters (Sophia Western being a character from Henry Fielding's novel Tom Jones). These works would have allowed Chalon to combine his skills in portraiture with narrative or symbolic content, appealing to the literary and sentimental tastes of the Victorian public.

His portraits of theatrical and operatic celebrities were also highly regarded. He painted renowned performers of his day, such as the celebrated Swedish soprano Jenny Lind, whose arrival in London caused a sensation. These portraits not only captured the likeness of these stars but also conveyed something of their stage presence and charisma, serving as important visual records of 19th-century performance culture.

Chalon and His Contemporaries: Collaboration and Context

Alfred Edward Chalon's career unfolded during a period of immense artistic activity and change in Britain. He was part of a vibrant community of artists, and his relationships with his contemporaries were multifaceted.

His closest artistic bond was undoubtedly with his brother, John James Chalon. They shared a studio for a time, often exhibited at the same venues, and, as mentioned, co-founded The Evening Sketching Society. There are accounts of them collaborating on works, with John James, known for his landscapes, perhaps painting the backgrounds, and Alfred focusing on the figures. This kind of artistic partnership, while not common, highlights their close working relationship.

Through the Royal Academy and sketching societies, Chalon would have known many of the leading artists of his day. These included established figures from the older generation and rising stars. The world of portraiture was competitive, with artists like Sir Martin Archer Shee (President of the Royal Academy after Lawrence), Sir Francis Grant (who later became PRA), and George Hayter all vying for prestigious commissions. Chalon's success, particularly in watercolour portraiture and with royal patronage, carved him a distinct and respected place.

In the broader field of watercolour, he was a contemporary of giants like J.M.W. Turner and David Cox, though their primary focus (landscape) differed from Chalon's figurative work. Nevertheless, the overall flourishing of the watercolour medium provided a supportive context for his own achievements.

The rise of illustrated journalism, with publications like The Illustrated London News (founded 1842), created new avenues for artists' work to reach a wider public through engravings. Chalon's popular images, especially of the Queen and other celebrities, were well-suited for reproduction and contributed to his public profile.

While Chalon's style was generally aligned with the prevailing Romantic and early Victorian aesthetics, the art world was not static. By the mid-century, new movements were emerging. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by artists like William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, challenged Academic conventions with their emphasis on truth to nature, bright colours, and detailed realism. While Chalon's work did not directly engage with Pre-Raphaelite principles, their emergence signifies the evolving artistic landscape in which he operated during his later career.

It's also noted that the Chalon brothers, being of Swiss origin, were sometimes considered part of an émigré community within the London art scene. While they were well-integrated and achieved significant success, this background might have subtly influenced their position or perception within certain circles.

Later Years, Declining Fortunes, and Legacy

Despite his earlier successes and royal favour, Alfred Edward Chalon's later years were marked by a decline in popularity and perhaps financial stability. Artistic tastes are notoriously fickle, and by the 1850s, new styles and younger artists were capturing public attention. In 1855, he and his brother John James held a joint exhibition of their works at the Society of Arts in Adelphi, but it reportedly met with a muted response, a poignant indicator of their waning prominence.

The brothers, both bachelors, lived together in their final years at a house in Campden Hill, Kensington, a quiet and then somewhat suburban part of London. John James Chalon passed away in 1854. Alfred Edward Chalon outlived his brother by six years, dying on October 3, 1860, at the age of 80. He was buried in Highgate Cemetery, a resting place for many notable Victorians.

Despite the dimming of his fame in his last decade, Alfred Edward Chalon left a significant artistic legacy. His portraits, particularly those of Queen Victoria and other prominent figures, remain important historical documents, offering vivid insights into the personalities and fashions of the early to mid-Victorian era. His "Chalon Head" on colonial stamps gave his work an unprecedented global reach for an artist of his time.

As an art historian, one evaluates Chalon not only for his technical skill – his fluid draughtsmanship, his delicate handling of watercolour, his ability to capture a likeness – but also for his role in reflecting and shaping the visual culture of his age. He was a master of the society portrait, imbuing it with charm and elegance. His contributions to the tradition of British watercolour painting are notable, particularly in the realm of figurative work.

His influence on subsequent portraitists may have been more indirect than direct, but his success demonstrated the potential of watercolour for sophisticated and fashionable portraiture. His works are held in numerous public collections, including the Royal Collection, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the National Portrait Gallery in London, ensuring their accessibility for future generations of scholars and art lovers.

Conclusion: An Enduring Image-Maker

Alfred Edward Chalon stands as a distinguished figure in 19th-century British art. From his Swiss origins, he rose to become a Royal Academician and a favoured painter of Queen Victoria, a testament to his talent and his ability to connect with the spirit of his times. His watercolours, celebrated for their elegance, vivacity, and insightful characterization, provide a captivating window onto the world of Victorian high society.

His iconic image of the young Queen Victoria, disseminated through prints and postage stamps, became one ofthe most recognizable royal portraits of the era, securing him a unique place in both art history and popular culture. While his fame may have waned in his later years, the quality of his best work and his historical significance ensure his enduring reputation as a skilled and influential artist who masterfully captured the likeness and the aspirations of a remarkable age. His legacy is preserved not only in the galleries that house his paintings but also in the enduring visual record he created of a transformative period in British history.