Robert Campin stands as a pivotal figure in the art history of Northern Europe, recognized as one of the earliest and most influential masters of Early Netherlandish painting. Active during the first half of the 15th century, his work marks a significant departure from the prevailing International Gothic style, ushering in a new era of realism and technical innovation that would define the Northern Renaissance. Though shrouded in some historical ambiguity, particularly concerning the attribution of his works, Campin's impact as an artist and teacher is undeniable, laying crucial groundwork for subsequent generations of painters.

Life and Career in Tournai

Born around 1375, Robert Campin's life and career were primarily centered in the prosperous city of Tournai, located in present-day Belgium. Archival records indicate his presence in Tournai from at least 1406. He acquired citizenship in 1410, suggesting he was establishing himself professionally and socially within the city. Campin became a respected master painter, operating a large and successful workshop. His standing within the artistic community is confirmed by his appointment as dean of the painters' guild, the Guild of Saint Luke, in 1423.

Campin's civic involvement extended beyond the painters' guild. Records show he held positions such as subdeacon and inspector within the guild structure, which likely encompassed goldsmiths as well, reflecting the interconnectedness of crafts during this period. He achieved a relatively high social status in Tournai, participating in civic life and engaging with the city's governance.

However, Campin's life was not without controversy. In 1432, he faced legal trouble stemming from his political affiliations and a personal scandal involving an extramarital affair. He was initially sentenced to a year's banishment from Tournai. This sentence was later commuted, reportedly through the intervention of Jacqueline, Countess of Hainaut, indicating Campin possessed influential connections. Despite these troubles, he continued to work as a painter until his death in Tournai in 1444.

The Master of Flémalle Enigma

One of the most persistent discussions surrounding Robert Campin involves his identification with the anonymous artist known as the "Master of Flémalle." This name was coined by art historians in the late 19th century to designate the creator of a group of stylistically related paintings, initially thought to have originated from an abbey in Flémalle, near Liège (though this provenance was later questioned). These works, including panels like the Saint Veronica and The Trinity, displayed a robust, sculptural realism and a focus on tangible detail that distinguished them from contemporary art.

The stylistic characteristics of the Flémalle group closely matched documented aspects of Campin's known activity and influence. Crucial evidence emerged from documents related to two pupils documented as being in Campin's workshop: Jacques Daret and Rogier van der Weyden (then known as Rogelet de le Pasture). An altarpiece known to be by Daret showed strong stylistic similarities to the Flémalle group, suggesting a common source of training.

Based on this and other stylistic and circumstantial evidence, most art historians now equate Robert Campin with the Master of Flémalle. This identification places him as the author of key works previously attributed to the anonymous master, significantly shaping our understanding of his oeuvre and his pioneering role. However, the lack of definitively signed works by Campin means the identification, while widely accepted, still relies on scholarly consensus and interpretation of historical records and stylistic analysis.

Technical Innovation: Mastering the Oil Medium

Robert Campin is celebrated as one of the earliest Netherlandish artists to fully exploit the potential of oil painting. While oil had been used previously for certain purposes, Campin, alongside contemporaries like Jan van Eyck, pioneered its use as the primary medium for panel painting, moving away from the faster-drying egg tempera that had dominated medieval art.

The use of oil binders allowed for a slower drying time, giving artists unprecedented control over their medium. This enabled the meticulous blending of colours, the creation of subtle gradations of tone, and the application of translucent glazes. These glazes allowed light to penetrate layers of paint and reflect off the prepared white ground of the panel, creating a luminous, jewel-like quality and a depth of colour previously unattainable.

Campin's mastery of oil paint is evident in the astonishing level of detail and realism in his works. He rendered textures – the gleam of metal, the roughness of wood, the softness of fur, the intricate patterns of textiles – with remarkable fidelity. This technical facility was fundamental to the new naturalistic aesthetic he pursued, allowing him to create images that appeared more tangible and lifelike than ever before. This technical revolution was a cornerstone of the Early Netherlandish style.

Artistic Style: A New Vision of Realism

Campin's art represents a decisive break from the elegant, courtly, and often idealized International Gothic style. He embraced a more robust and grounded realism, focusing on the tangible world and the specific details of everyday life. His figures possess a physical presence and sculptural quality, often appearing solid and weighty within their depicted spaces.

He demonstrated a keen interest in rendering the effects of light and shadow, using them to model forms and create a sense of volume. While his understanding of linear perspective was perhaps more intuitive than the mathematically precise systems being developed in Italy, he skillfully constructed believable interior and exterior spaces, often using tilted perspectives or multiple viewpoints to enhance the narrative or focus attention.

A hallmark of Campin's style is the integration of religious subjects into contemporary domestic settings. Sacred events, like the Annunciation in the Merode Altarpiece, unfold not in ethereal, otherworldly locations, but in meticulously detailed Flemish interiors, complete with furniture, household objects, and views through windows onto city streets. This approach made religious narratives more immediate and relatable to contemporary viewers. He also excelled at capturing human emotion, moving beyond stereotypical representations to depict more individualized and psychologically nuanced figures.

Complex Iconography and Disguised Symbolism

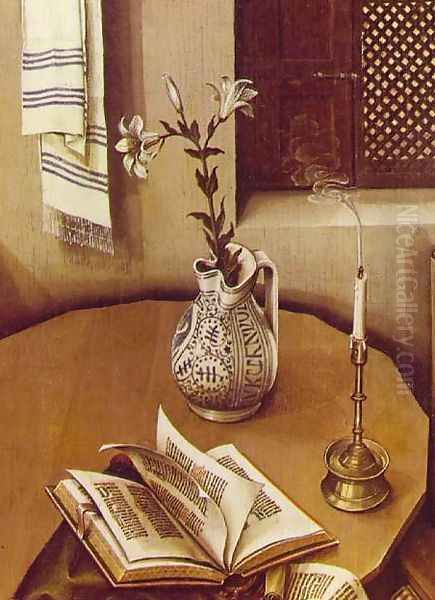

Beyond their surface realism, Campin's paintings are often rich in complex iconography and symbolism. He was a master of what art historian Erwin Panofsky termed "disguised symbolism," where ordinary, everyday objects within the realistic setting carry deeper religious meanings. This technique allowed Campin to infuse his seemingly secular details with profound theological significance, inviting viewers to contemplate the spiritual dimensions hidden within the material world.

In the Merode Altarpiece, for example, numerous objects contribute to the painting's meaning. The spotless room and the laver (water basin) and towel can symbolize Mary's purity. The lilies on the table are a traditional symbol of her virginity. A tiny figure of the Christ Child carrying a cross, visible streaming in on a ray of light, represents the Incarnation. Even seemingly mundane details, like the mousetrap Joseph is crafting in the right wing, have been interpreted by scholars as symbols of Christ trapping the Devil.

This layering of meaning added intellectual depth to his works, engaging viewers on multiple levels. It reflected the complex religious piety of the era, where the divine was seen as immanent in the everyday world. Campin's ability to seamlessly weave together detailed realism and intricate symbolism was a major contribution to the development of Northern Renaissance art.

Major Works: A Closer Examination

Several key works are central to understanding Robert Campin's artistic achievement, assuming the identification with the Master of Flémalle is correct.

The Merode Altarpiece (c. 1427-1432): Perhaps his most famous work, this triptych (three-panelled altarpiece) is a masterpiece of Early Netherlandish painting, now housed in The Cloisters, part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The central panel depicts the Annunciation to Mary, set within a detailed contemporary Flemish interior. The left wing shows the kneeling donors, identified as Pieter Engelbrecht and his wife, witnessing the sacred event. The right wing portrays Saint Joseph in his workshop, diligently crafting mousetraps. The work is renowned for its vibrant colour, meticulous detail, complex spatial arrangement, and rich disguised symbolism. It exemplifies Campin's ability to blend the sacred and the mundane.

The Seilern Triptych (Entombment Triptych) (c. 1410-1420): An earlier work, now in the Courtauld Institute of Art, London. This triptych depicts the Entombment of Christ in the center, flanked by the Resurrection and donor portraits with saints on the wings. Compared to the Merode Altarpiece, the style is somewhat more archaic, still showing links to the International Gothic in the decorative background of the central panel. However, the figures display a powerful emotional intensity and physical weight that foreshadows his mature style. The depiction of grief and sorrow is particularly striking.

Portraiture: Campin was also a significant portraitist. Surviving examples, such as the Portrait of a Man and Portrait of a Woman (c. 1430-1435) in the National Gallery, London, likely intended as a pair (possibly husband and wife), showcase his ability to capture individual likeness and character with unflinching realism. The Portrait of a Fat Man (or Robert de Masmines?) (c. 1425), known through versions in Berlin and Madrid, is another powerful example of his direct and unidealized approach to portraiture. These portraits are notable for their strong sculptural modeling and psychological presence.

Other important works attributed to Campin or his workshop include the Nativity (c. 1420, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon), The Marriage of the Virgin (c. 1420, Museo del Prado, Madrid), and fragments of larger altarpieces, all contributing to our understanding of his artistic range and development.

Workshop Practice and Influential Teaching

Robert Campin operated a large and productive workshop in Tournai, which played a crucial role in disseminating his style and techniques. He trained numerous apprentices, ensuring the continuation and development of the new realistic approach to painting. The scale of his operation is suggested by the number of documented pupils and the volume of work attributed to him and his circle.

His two most famous pupils were Jacques Daret and Rogier van der Weyden (recorded in the workshop as Rogelet de le Pasture). Daret's documented works, such as the panels from the St. Vaast Altarpiece (1434-1435), provide key stylistic links back to Campin. Rogier van der Weyden, who entered Campin's workshop relatively late (around 1427) and became an independent master in 1432, would go on to become one of the most influential painters of the entire Netherlandish school, second perhaps only to Jan van Eyck.

The exact nature of the relationship between Campin and Van der Weyden remains debated – was Van der Weyden simply a pupil, or perhaps a more established collaborator? Regardless, Van der Weyden's early work clearly shows Campin's profound influence in its sculptural figures, emotional intensity, and realistic detail, though Van der Weyden would develop a more refined, elegant, and emotionally charged style of his own. Another documented apprentice was Wynant van der Goes. Campin's role as a teacher was thus fundamental to the flourishing of the Tournai school and the broader Early Netherlandish tradition.

Campin's Wider Impact and Legacy

Robert Campin's contributions were foundational for the Northern Renaissance. His pioneering work in oil painting and his development of a robust, detailed realism profoundly influenced his contemporaries and subsequent generations. While Jan van Eyck, active slightly later, achieved perhaps even greater heights of illusionism and technical refinement, Campin's innovations were crucial in paving the way. Some scholars even suggest Campin's influence might be discernible in Van Eyck's earlier works, though the relationship between these two giants remains a subject of study.

Campin's influence, often transmitted through his student Rogier van der Weyden, spread throughout the Netherlands and beyond. Artists like Petrus Christus, active in Bruges after Van Eyck, show awareness of the stylistic trends established by both masters. Dieric Bouts, working in Leuven, synthesized elements from Van Eyck and Van der Weyden, reflecting the widespread impact of this new realism. Later Netherlandish masters such as Hugo van der Goes and Hans Memling continued to build upon the foundations laid by Campin and his generation.

His impact may have extended even further. The intense realism and detailed observation characteristic of Early Netherlandish painting fascinated artists across Europe, including those in Germany, France, Spain, and even Italy. Artists like Antonello da Messina are thought to have been influenced by Netherlandish oil techniques. Later Northern artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, greatly admired and studied the works of the Netherlandish pioneers.

Despite the attribution issues and the scandals of his personal life, Robert Campin's historical importance is secure. He was rediscovered by art historians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and his reputation has grown as his central role in the revolution of Northern European art has become clearer. He stands alongside the Van Eyck brothers and Rogier van der Weyden as one of the key figures who transformed painting in the 15th century.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Realism

Robert Campin emerges from the historical record and the analysis of his attributed works as a powerful innovator and a master craftsman. Active in Tournai, he ran a thriving workshop, navigated civic life with its attendant controversies, and, most importantly, forged a new artistic path. His embrace of the oil medium enabled an unprecedented level of realism, characterized by meticulous detail, tangible textures, strong modeling, and psychologically present figures.

By grounding sacred narratives in familiar, contemporary settings and imbuing everyday objects with profound symbolic meaning, he created works that resonated deeply with the religious sensibilities of his time while pushing the boundaries of artistic representation. The debate surrounding his identity as the Master of Flémalle highlights the challenges of reconstructing the careers of artists from this period, yet the core group of works associated with him reveals a consistent and forceful artistic personality.

Through his own paintings and through the influential pupils he trained, particularly Rogier van der Weyden, Robert Campin played an indispensable role in shaping the course of the Northern Renaissance. He was truly one of the founding fathers of Early Netherlandish painting, leaving a legacy of realism and technical mastery that would influence European art for centuries to come.