Lucas Cranach the Elder stands as one of the most significant and prolific artists of the Northern Renaissance. Active during a period of immense religious and social upheaval, Cranach navigated the complex currents of his time, serving princes, befriending reformers, and establishing a highly successful workshop that disseminated his distinctive style throughout Germany and beyond. His vast oeuvre encompasses evocative portraits, compelling religious scenes, intriguing mythological narratives, and a unique approach to the female nude, all rendered with a characteristic blend of Late Gothic linearity and burgeoning Renaissance sensibilities. More than just a painter, Cranach was also a skilled printmaker, a savvy businessman, and an influential civic figure, leaving an indelible mark on the art and culture of 16th-century Germany.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Vienna

Born around 1472 in the town of Kronach in Upper Franconia, from which he derived his name, Lucas likely received his initial artistic training from his father, Hans Maler (whose surname simply means "painter"). Little is known for certain about his earliest years, but the artistic environment of Franconia, still steeped in the traditions of Late Gothic art, would have provided his foundational visual language. This included an emphasis on expressive line, intricate detail, and emotional intensity, characteristics that would remain visible, albeit transformed, throughout his long career.

Around the turn of the century, perhaps seeking broader opportunities and exposure to new artistic currents, Cranach traveled south to Vienna. This period, roughly from 1500 to 1504, proved crucial for his development. Vienna was a vibrant center of humanist thought associated with its university. Cranach found patronage among these intellectual circles, painting portraits of scholars and academics. Notable works from this time, such as the double portraits of Johannes Cuspinian, a humanist scholar and rector of the university, and his wife Anna, demonstrate his burgeoning skill in capturing likeness and his innovative approach to portraiture, often integrating his subjects into richly detailed landscape settings.

His Viennese works also reveal a powerful engagement with landscape painting, arguably influenced by the emerging Danube School, a movement characterized by its expressive and atmospheric depictions of nature, associated with artists like Albrecht Altdorfer and Wolf Huber. Paintings like the Rest on the Flight into Egypt (c. 1504) or the early Crucifixion (c. 1503) showcase dramatic, almost mystical landscapes that nearly overwhelm the figures, highlighting Cranach's early fascination with the expressive potential of the natural world. This intensity and focus on landscape would become less dominant later in his career but remained an important element in his compositions.

Court Painter in Wittenberg

The year 1505 marked a pivotal turning point in Cranach's life and career. He was summoned to Wittenberg, the residence city of the Electorate of Saxony, to become court painter to Elector Frederick III, known as Frederick the Wise. This prestigious appointment provided Cranach with financial security, social standing, and a steady stream of commissions. Wittenberg, soon to become the epicenter of the Protestant Reformation, would be Cranach's home and primary center of activity for the next four decades.

Cranach served not only Frederick the Wise but also his successors, Elector John the Steadfast and Elector John Frederick the Magnanimous. His duties were diverse, ranging from painting portraits of the electoral family and court members to creating large-scale altarpieces for churches, designing decorations for festivities, and even providing patterns for coins and coats of arms. In recognition of his service and status, Frederick the Wise granted Cranach a coat of arms in 1508: a crowned, winged serpent holding a ring in its mouth. This emblem would become Cranach's signature, appearing on countless works produced by him and his workshop.

To meet the high demand for his art, Cranach established a large and highly efficient workshop in Wittenberg. This workshop employed numerous assistants and apprentices, including, eventually, his own sons. It functioned almost like a modern production line, enabling the creation of multiple versions of popular subjects, such as portraits of the Electors, images of Martin Luther, and Cranach's famous depictions of Venus or Lucretia. While this system ensured prolific output and wide dissemination of his style, it also sometimes complicates questions of attribution for specific works.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Innovations

Cranach's artistic style is unique, representing a fascinating synthesis of older German traditions and newer Renaissance ideas. He retained the emphasis on clear outlines, intricate detail, and expressive linearity characteristic of Late Gothic art, but he adapted these elements to new themes and formats. While aware of Italian Renaissance developments, particularly in the depiction of the human form and mythological subjects, he rarely adopted Italian principles of classical proportion, idealized beauty, or mathematically constructed perspective wholesale. Instead, he forged a distinctive Northern European visual language.

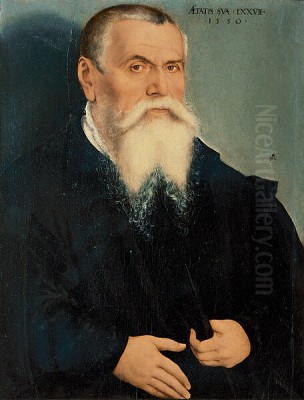

Portraiture: Cranach was a master portraitist, producing hundreds of likenesses throughout his career. His subjects included his patrons, the Saxon Electors, prominent figures of the Reformation like Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, other German nobles, and wealthy burghers. His portraits are often characterized by their clarity, precise rendering of costume and status symbols, and a certain elegant stylization. While some possess considerable psychological depth, others function more as formal representations of rank and identity. His iconic portraits of Luther were instrumental in shaping the public image of the reformer. He also painted powerful rulers like Emperor Charles V.

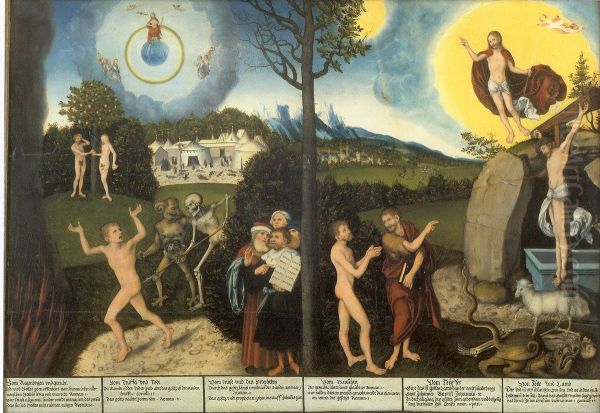

Religious Painting: Cranach's religious works reflect the dramatic shift in theological focus occurring during his lifetime. Before the Reformation gained full momentum, he produced traditional Catholic subjects. However, as a close associate of Luther, his later religious art became a vehicle for expressing Protestant ideas. He created major altarpieces for churches in Wittenberg and Weimar, often incorporating portraits of the reformers and illustrating key Lutheran doctrines, such as justification by faith alone. The didactic painting Law and Grace (c. 1529), likely developed in consultation with Luther, visually contrasts the path to salvation through God's grace (Gospel) with the damnation resulting from reliance on adherence to the Law.

Mythology and the Nude: Cranach is perhaps most famous today for his numerous depictions of mythological scenes and female nudes. Subjects like Venus (often paired with Cupid), Lucretia (the virtuous Roman heroine), Judith, Salome, and The Judgment of Paris appear frequently. His female nudes are highly distinctive: slender, pale-skinned figures with small breasts, rounded abdomens, and elongated limbs, often posed with a subtle, almost mannered elegance. They frequently wear elaborate hats or jewelry and are set against dark, plain backgrounds or stylized landscapes. These works often carry complex allegorical or moralizing meanings, exploring themes of love, temptation, virtue, and folly, sometimes with a playful or subtly erotic undertone that appealed to his courtly patrons. His Adam and Eve compositions also fall into this category, blending biblical narrative with his characteristic figural style.

Printmaking: Alongside his painting activities, Cranach was a highly accomplished printmaker, primarily in woodcut but also engraving. His prints served various purposes: illustrating books (most notably Luther's German translation of the New Testament), creating independent devotional or allegorical images, and reproducing popular painted compositions. Printmaking allowed for wider distribution of his imagery and played a significant role in disseminating both his artistic style and the visual culture of the Reformation. His woodcuts often display the same linear energy and clarity found in his paintings.

Landscape and Symbolism: While the dramatic intensity of his early Viennese landscapes subsided, Cranach continued to incorporate landscape elements into many paintings, often featuring stylized trees, rocks, and distant castles. Nature frequently serves as more than mere background, contributing to the mood or narrative. His work is also rich in symbolism, most obviously his winged serpent signature, but also through the attributes accompanying figures (like Lucretia's dagger or Venus's apple) and the complex iconography of allegorical works like Melancholy (1532), a fascinating counterpart to Albrecht Dürer's famous engraving Melencolia I.

The Cranach Workshop and Family Legacy

The success and prolific output of Lucas Cranach the Elder were inextricably linked to his large workshop. This efficient operation allowed him to fulfill numerous commissions simultaneously and to produce multiple versions of popular compositions, adapting them to suit different patrons or price points. Standardized patterns and techniques were likely employed, ensuring consistency in style and quality, though the level of the master's personal involvement undoubtedly varied.

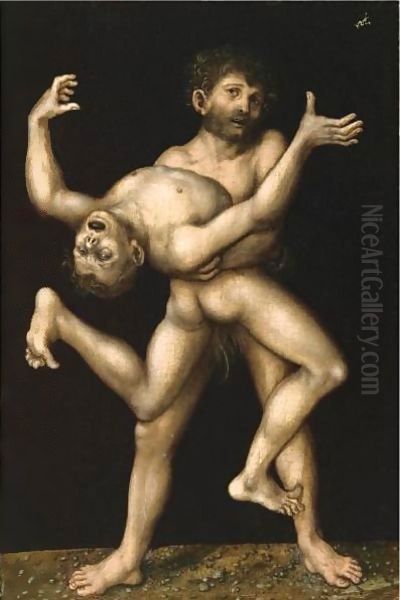

Cranach trained numerous artists in his workshop, ensuring the continuation of his stylistic influence. Most significantly, he trained his own sons, Hans Cranach (c. 1513–1537) and Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515–1586). Hans showed considerable promise, and works attributed to him, like Hercules and Antaeus, suggest a powerful and dynamic style, but his career was cut short by his early death while traveling in Italy.

Lucas the Younger became his father's primary collaborator and eventual successor. He took over the management of the workshop after his father followed Elector John Frederick into exile and continued its operation after his father's death. Lucas the Younger worked very much in his father's style, making definitive attribution difficult for many works produced during the period of their collaboration (roughly the 1530s and 1540s). However, subtle differences can often be discerned: the son's figures are sometimes softer, his compositions occasionally more crowded, and his rendering of fabrics and details even more elaborate. He successfully maintained the workshop's reputation and productivity well into the later 16th century. The sheer volume of work associated with the Cranach name is a testament to this family enterprise.

Cranach and the Protestant Reformation

Lucas Cranach the Elder's life and work are deeply intertwined with the Protestant Reformation. Residing in Wittenberg, the very heart of the movement, Cranach developed close personal relationships with its key figures. He was a close friend of Martin Luther; they were neighbors, Cranach acted as godfather to Luther's first son, Johannes, and witnessed Luther's marriage to Katharina von Bora. He was also well-acquainted with Philipp Melanchthon, the humanist scholar and Luther's chief collaborator.

This proximity placed Cranach in a unique position to become the primary visual artist of the early Reformation. He created numerous portraits of Luther, beginning around 1520, which were widely copied in paintings and prints by his workshop. These images were crucial in establishing Luther's visual identity and disseminating his likeness throughout Europe, serving as icons for the burgeoning Protestant movement. He similarly created influential portraits of Melanchthon and other reformers.

Beyond portraiture, Cranach's workshop produced art that directly served the Reformation's cause. He provided the woodcut illustrations for Luther's influential German translation of the New Testament (the "September Testament" of 1522), including anti-Papal imagery in the illustrations for the Book of Revelation. Didactic paintings like Law and Grace visually articulated core Lutheran theological concepts for a wider audience. Altarpieces created for Lutheran churches, such as the Wittenberg Altarpiece (finished by his son) and the later Weimar Altarpiece (featuring Cranach himself alongside Luther and John the Baptist at the foot of the cross), replaced traditional Catholic iconography with imagery centered on Christ's sacrifice and the sacraments as understood by Protestants.

Cranach also leveraged his business acumen for the cause, establishing a printing press in partnership with Christian Döring, which published Reformation tracts and pamphlets. He also owned a pharmacy. Despite his clear personal commitment to the Lutheran cause, Cranach was also a pragmatic businessman. He continued to accept commissions from Catholic patrons, most notably Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, one of Luther's chief adversaries, for whom he painted portraits and religious works. This demonstrates the complex realities of patronage and artistic production during this religiously divided era.

Analysis of Key Representative Works

Cranach's vast output includes many masterpieces. Examining a few highlights reveals the core aspects of his artistry:

Portraits of Martin Luther: Cranach painted Luther at various stages of his life, from the determined monk challenging the Church to the established reformer and family man. Early portraits emphasize his intensity, while later ones show a more settled, sometimes heavier figure. These images, endlessly replicated by the workshop, fixed Luther's appearance in the public imagination and served as powerful symbols of the Reformation itself.

Law and Grace (c. 1529): This complex allegorical panel, existing in several versions, is a visual sermon on Lutheran doctrine. Typically divided into two halves, one side depicts Old Testament scenes (Adam and Eve, Moses receiving the Law, a man pursued by Death and the Devil), representing damnation through the Law. The other side shows New Testament scenes (the Annunciation to the Shepherds, Christ on the Cross, Christ Resurrected), representing salvation through faith in Christ's sacrifice (Grace). John the Baptist often directs a figure representing humanity towards the crucified Christ. It's a prime example of art used for theological instruction.

Adam and Eve (multiple versions, e.g., 1526, 1528): Cranach returned to this theme often. Compared to Albrecht Dürer's famous 1504 engraving of the subject, which emphasizes classical proportions and anatomical study, Cranach's figures are more stylized, slender, and subtly erotic, fitting his characteristic nude type. Eve is typically shown offering the apple to a somewhat hesitant Adam, set within a detailed, Edenic landscape often populated with animals. The works explore themes of temptation, the Fall, and human frailty.

Venus (various versions, e.g., Venus with Cupid the Honey Thief, c. 1527): Cranach's depictions of Venus, the Roman goddess of love, are among his most recognizable works. Often shown nude or nearly nude, adorned with jewelry or a transparent veil, she embodies a courtly, somewhat detached sensuality rather than classical voluptuousness. The version where Cupid complains after being stung by bees while stealing honey allows for a moralizing inscription about the fleeting nature of pleasure and the pain that often accompanies desire, adding an intellectual layer typical of Northern Renaissance art.

The Ill-Matched Lovers (c. 1530s): This popular theme, treated by Cranach and his workshop multiple times, depicts an elderly, often lecherous man being seduced or robbed by an attractive young woman (sometimes aided by an accomplice). It served as a satirical commentary on foolishness, lust, and the dangers of unequal relationships, reflecting contemporary social anxieties and moral attitudes. The detailed rendering of expressions and interactions adds to the narrative force.

Weimar Altarpiece (center panel completed 1555 by Lucas Cranach the Younger): Although finished after his death by his son based on his designs, the center panel of this triptych in the Stadtkirche St. Peter und Paul in Weimar is a powerful testament to Cranach's Lutheran faith. It depicts Christ crucified, with blood streaming from his side onto Cranach's own head as he stands alongside John the Baptist and Martin Luther. Luther points to biblical text, emphasizing the centrality of scripture. It's a deeply personal and theological statement about salvation through Christ alone.

Contemporaries, Influence, and Artistic Context

Lucas Cranach the Elder worked during a golden age of German art, alongside several other towering figures. His most famous contemporary was Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) of Nuremberg. While both artists engaged with Renaissance ideas, their styles differed significantly. Dürer embraced Italian theories of proportion and perspective more fully, achieving a synthesis of Northern detail and Southern classicism. Cranach remained more rooted in Gothic linearity and developed a more stylized, courtly aesthetic. They were undoubtedly aware of each other's work, but direct interaction seems limited.

Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/8-1543), primarily active in Basel and later England, was another major figure, renowned for his incredibly realistic and psychologically penetrating portraits. While both Cranach and Holbein were master portraitists, Holbein's meticulous realism contrasts with Cranach's more linear and sometimes decorative approach.

Matthias Grünewald (c. 1470/80-1528) represents a different facet of German art, known for the intense emotionalism and visionary expressionism of works like the Isenheim Altarpiece. Compared to Grünewald's visceral intensity, Cranach's art often appears more restrained and elegant, even when depicting dramatic subjects.

Other important German artists of the period include Albrecht Altdorfer (c. 1480-1538) and Wolf Huber (c. 1485-1553), key figures of the Danube School whose emphasis on expressive landscape influenced Cranach's early work. Hans Baldung Grien (c. 1484/5-1545), a pupil of Dürer, developed a distinctive and sometimes unsettling style. Printmakers like Georg Pencz, Barthel Beham, and Michael Ostendorfer also contributed significantly to the artistic landscape.

Cranach was certainly aware of Italian art, perhaps through prints or the experiences of contemporaries. His adoption of mythological themes and the nude reflects this awareness. However, he adapted these influences into his own distinctly Northern idiom rather than simply imitating Italian models. Netherlandish artists like Jan Gossaert or perhaps even the imaginative works of Hieronymus Bosch might also have offered points of reference. Cranach's own influence was spread primarily through his workshop's prolific output and the work of his sons and pupils, like Wolfgang Krodell. His style shaped courtly art in Saxony and other Protestant regions of Germany for decades.

Civic Life, Business Ventures, and Later Years

Beyond his artistic endeavors, Lucas Cranach the Elder was a prominent and respected citizen of Wittenberg. He was a shrewd businessman, complementing his income from art with other ventures. Most notably, he owned and operated the town's pharmacy from 1520 onwards, a profitable enterprise. Evidence suggests he may also have been involved in bookselling and the wine trade. These activities allowed him to accumulate considerable wealth and property, making him one of Wittenberg's richest residents.

His social standing and wealth led to civic responsibilities. He served multiple terms on the Wittenberg city council and was elected Bürgermeister (Mayor) three times (1537/38, 1540/41, and 1543/44). This level of civic engagement by a leading artist was unusual and speaks to Cranach's respected position within the community.

Cranach remained loyal to his patrons, the Saxon Electors. This loyalty was tested after the Schmalkaldic War (1546-47), in which the Protestant Schmalkaldic League, led by Elector John Frederick, was defeated by Emperor Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg. John Frederick was captured and stripped of the electoral title and much of his territory. When the deposed Elector was eventually released but confined first to Augsburg and then Weimar, the elderly Cranach chose to join him in 1550, leaving the thriving Wittenberg workshop under the management of his son, Lucas the Younger. He spent his final years in the service of his captive patron. Lucas Cranach the Elder died in Weimar on October 16, 1553, at the advanced age of about 81.

Conclusion: A Legacy in Art and History

Lucas Cranach the Elder was far more than just a court painter. He was a pivotal figure whose career bridged the late Gothic and Renaissance periods in Germany, and whose life was intimately connected with the tumultuous events of the Protestant Reformation. His distinctive artistic style, characterized by elegant linearity, detailed observation, and a unique approach to the human form, particularly the female nude, left a lasting imprint on German art.

Through his prolific workshop, he not only fulfilled the demands of his courtly and civic patrons but also played a crucial role in shaping the visual culture of Lutheranism, creating enduring images of its leaders and illustrating its core tenets. As a successful entrepreneur and respected civic leader, he embodied the multifaceted possibilities of life for an artist in the 16th century. His vast and varied body of work continues to fascinate scholars and the public alike, offering insights into the art, religion, and society of a transformative era in European history. Cranach's legacy endures in the numerous paintings and prints housed in collections worldwide, testament to a long, productive, and historically significant life.