Rudolf Ernst stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th and early 20th-century European art, particularly renowned for his contributions to the Orientalist movement. Born in Austria but spending much of his productive career in France, Ernst captured the European imagination with his meticulously detailed and evocative depictions of life, architecture, and culture in North Africa and the Middle East. His work, characterized by technical brilliance and a romantic sensibility, offers a window into the Western fascination with the "Orient" during a period of expanding global interaction and colonial presence.

Early Life and Training in Vienna

Rudolf Ernst was born on February 14, 1854, in Vienna, the heart of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He entered a world steeped in artistic tradition; his father, Leopold Ernst, was an architect and a member of the prestigious Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. This familial connection to the arts undoubtedly fostered young Rudolf's inclinations. Growing up in Vienna also meant experiencing a period of significant political and social upheaval, including the echoes of the 1848 Revolutions and the subsequent Vienna Uprising, events that shaped the cultural atmosphere of his youth.

Encouraged by his father, Ernst enrolled at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts at the young age of fifteen. This institution was a bastion of academic tradition, emphasizing rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and historical painting. During his time there, Ernst studied under prominent figures such as August Eisenmenger, known for his historical and monumental works, and the highly respected Anselm Feuerbach, a leading proponent of Neoclassicism and historical painting in the German-speaking world. Feuerbach's emphasis on classical ideals and meticulous execution likely left a lasting impression on Ernst's developing style.

Following his initial training, Ernst sought to broaden his artistic horizons. Like many aspiring artists of his time, he traveled to Rome. Italy, with its wealth of classical antiquity and Renaissance masterpieces, was considered an essential destination for artistic pilgrimage. In Rome, Ernst dedicated himself to studying and copying the works of the Old Masters, further honing his technical skills and absorbing the lessons of composition, form, and color from historical precedents. He later returned to Vienna to continue his studies, consolidating his academic foundation.

The Move to Paris and the Allure of the Orient

In 1876, seeking greater opportunities and exposure within the vibrant European art scene, Rudolf Ernst made the pivotal decision to relocate to Paris. Paris was, at this time, the undisputed capital of the art world, attracting artists from across Europe and America. It was the center of innovation, debate, and, crucially, the marketplace for art. Settling in Paris marked a turning point in Ernst's career and artistic direction.

Shortly after his arrival, Ernst began exhibiting his work at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their reputations. His initial submissions likely included portraits and genre scenes, reflecting his academic training. However, Paris was also a hub for the burgeoning Orientalist movement, a genre that captivated both artists and the public.

Orientalism, as an artistic and cultural phenomenon, reflected a deep-seated European fascination with the cultures of North Africa, the Middle East (often referred to as the Levant), and sometimes further afield in Asia. Fueled by increased travel, colonial expansion, archaeological discoveries, and romantic literature, artists sought to depict the perceived exoticism, sensuality, history, and daily life of these regions. Figures like Eugène Delacroix had earlier paved the way with dramatic depictions inspired by his travels, while artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme were achieving immense success with highly detailed, almost photographic renderings of Eastern scenes. Ernst soon found himself drawn to this compelling genre.

Travels and Research: Sourcing Authenticity

A defining characteristic of many Orientalist painters, including Ernst, was their commitment to achieving a sense of authenticity, often through travel and research. While some artists relied on second-hand accounts, studio props, and photographs, Ernst undertook several significant journeys to gather first-hand experience and materials. He traveled extensively, visiting Spain (particularly Andalusia with its Moorish heritage), Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, and Turkey (specifically Constantinople, modern-day Istanbul).

These travels were not mere tourist excursions; they were research expeditions. Ernst immersed himself in the environments he wished to depict. He sketched architectural details, observed local customs, studied the play of light on different surfaces, and collected a vast array of objects. His studio in Paris became a treasure trove of artifacts brought back from his journeys: textiles, carpets, ceramics, metalwork, furniture, musical instruments, and traditional clothing. He also utilized photography, a tool increasingly employed by artists for documentation, to capture details he could later incorporate into his paintings.

This dedication to research provided the foundation for the remarkable detail and verisimilitude found in his work. While his compositions were often carefully constructed studio creations, sometimes combining elements from different locations or times, the individual components – the intricate tilework of a mosque wall, the pattern of a rug, the specific design of a hookah pipe – were rendered with painstaking accuracy based on his observations and collections. This meticulous approach lent his paintings an air of ethnographic authority, even as they presented a romanticized vision.

The Height of Orientalist Painting: Style and Themes

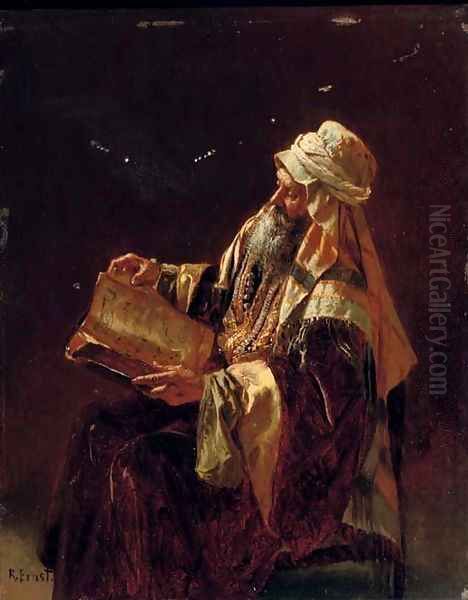

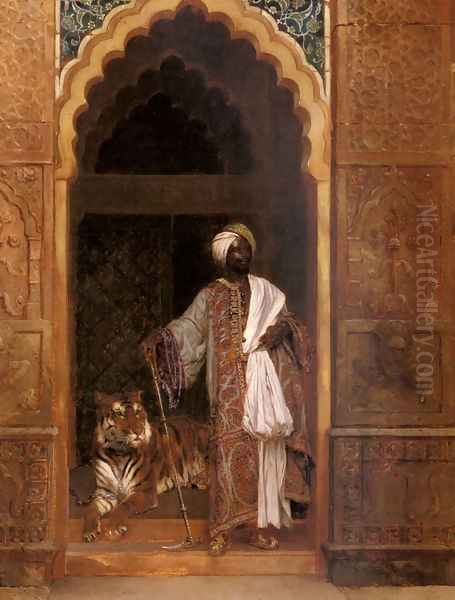

Rudolf Ernst's mature style solidified his reputation as a leading Orientalist painter. His work is characterized by a highly polished, academic technique. He applied paint smoothly, often on panel rather than canvas, allowing for exceptionally fine detail and minimizing visible brushstrokes. This meticulous finish, inherited from his academic training and influenced by masters like Gérôme, contributed to the almost photographic clarity of his scenes.

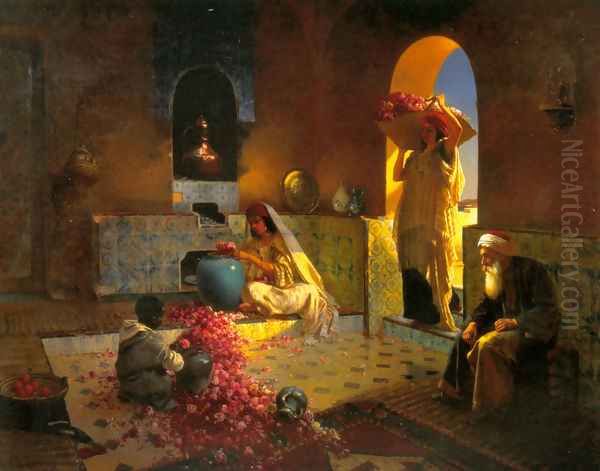

His use of color was rich and evocative, often employing warm palettes to convey the sun-drenched atmospheres of North Africa and the opulent interiors of Middle Eastern dwellings. He masterfully captured the interplay of light and shadow, whether illuminating the intricate details of a tiled wall, filtering through a latticed window (mashrabiya), or reflecting off polished metal surfaces. Texture was another key element; Ernst excelled at rendering the distinct surfaces of various materials – the soft pile of carpets, the cool smoothness of marble, the intricate inlay of mother-of-pearl, the sheen of silk garments, and the detailed patterns of Iznik tiles.

Ernst's subject matter typically revolved around serene and contemplative scenes rather than dramatic historical events. He frequently depicted the interiors of mosques, often focusing on moments of quiet prayer or study, as seen in works like After Prayer. Scholars reading manuscripts, guards relaxing in ornate palace corridors, musicians playing traditional instruments (such as in The Flute Player), and artisans at work were common themes. He also painted scenes of daily life, such as market interactions or intimate domestic settings.

While some Orientalists focused heavily on harem scenes, often playing to Western fantasies of sensuality and seclusion, Ernst's depictions of women, such as Maiden of Tangier or figures within domestic interiors, tended to be more reserved, though still imbued with an exotic allure. Notable works like The Letter (1888) and The Chess Party showcase his ability to create narrative vignettes within richly detailed settings, inviting the viewer into a seemingly private moment. Entering the Palace Gardens and scenes titled Turkish Bath further exemplify his interest in architectural spaces and genre scenes within an Orientalist context.

Artistic Circle and Influences

Rudolf Ernst did not work in isolation. In Paris, he became part of a circle of artists who shared similar interests, particularly in Orientalist themes. One of his closest associates was Ludwig Deutsch, another Vienna-born painter who had also relocated to Paris and specialized in Orientalism. Ernst and Deutsch were friends and, to some extent, artistic rivals. They shared a remarkably similar style, characterized by meticulous detail, a high degree of finish, and a focus on specific character types and architectural settings. They often exhibited together at the Paris Salon, reinforcing their shared identity as leading figures of the Austro-German school of Orientalism in Paris.

The influence of the French academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme on both Ernst and Deutsch cannot be overstated. Gérôme was a towering figure at the Salon, celebrated for his historical paintings and, especially, his highly detailed and dramatically lit Orientalist scenes. His precision, ethnographic (though often staged) detail, and smooth finish set a standard that many, including Ernst, sought to emulate. Ernst absorbed Gérôme's technical approach while developing his own preferred subjects and slightly warmer palette.

Beyond Deutsch and Gérôme, Ernst's work exists within the broader context of 19th-century Orientalism. He followed in the footsteps of earlier Romantics like Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Chassériau, who brought a passionate energy to North African subjects. He was contemporary with other prominent Orientalists such as the French painters Eugène Fromentin, Gustave Guillaumet, and Benjamin-Constant, each offering different perspectives on the landscapes and peoples of North Africa.

The British tradition, represented by artists like John Frederick Lewis, known for his incredibly detailed watercolors of Cairo interiors, and David Roberts, famous for his topographical views of Egypt and the Holy Land, also contributed to the visual vocabulary of Orientalism. The Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny, with his dazzling technique and vibrant depictions of Moroccan life, was another influential figure whose work resonated across Europe. Ernst's meticulous attention to detail also finds parallels in the work of the German Orientalist Gustav Bauernfeind. American artists working in Paris, like Frederick Arthur Bridgman, also explored similar themes, contributing to the international appeal of the genre. Ernst navigated this rich artistic landscape, borrowing, adapting, and ultimately forging his own distinct niche.

Beyond Painting: Ceramics and Printmaking

While primarily known as a painter, Rudolf Ernst's artistic interests extended to other media, notably ceramics and printmaking. His fascination with the decorative arts of the Islamic world, particularly the intricate tilework he observed during his travels, inspired him to experiment with ceramics himself. For a time, he operated a workshop or shop in the Montparnasse district of Paris dedicated to producing faience tiles.

These tiles often featured Orientalist motifs directly drawn from his paintings or inspired by Islamic designs. This venture reflects a broader trend in the late 19th century, influenced by movements like Arts and Crafts and Japonisme, where artists sought to break down the barriers between fine art and decorative art, often drawing inspiration from non-European traditions. Ernst's ceramic work allowed him to explore the patterns, colors, and textures he admired in Middle Eastern architecture in a different medium.

Ernst also engaged in printmaking, likely creating etchings or other forms of prints based on his popular paintings. This practice allowed his images to reach a wider audience beyond the collectors who could afford his unique oil paintings. His involvement in these diverse media underscores the depth of his engagement with the visual culture of the "Orient," extending beyond pictorial representation to encompass its material and decorative aspects.

Exhibitions, Awards, and Recognition

Throughout his career in Paris, Rudolf Ernst consistently sought recognition through official channels, primarily the annual Paris Salon (Salon des Artistes Français). Regular participation in the Salon was crucial for visibility and sales. His meticulously crafted and exotically themed paintings proved popular with both the critics and the public, appealing to the prevailing taste for detailed realism combined with intriguing subject matter.

His success was formally acknowledged through several awards. Notably, he received a bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1889, a major international event showcasing achievements in science, industry, and the arts. He achieved further recognition with an honorable mention at the Exposition Universelle of 1900, also held in Paris. These accolades solidified his standing within the art establishment and enhanced his reputation among collectors.

Ernst's paintings found favor with affluent patrons in Europe and America who were eager to acquire depictions of the exotic East. His works entered numerous private collections, and their detailed beauty and accessible subject matter ensured their enduring appeal. He became one of the most commercially successful Orientalist painters of his generation, alongside figures like Deutsch and Gérôme.

Later Life and Artistic Evolution

Rudolf Ernst continued to paint and exhibit well into the early 20th century. While the avant-garde movements like Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism were revolutionizing the art world in Paris, Ernst remained largely faithful to the academic Orientalist style that had brought him success. There is little evidence of significant stylistic evolution in his later work; he continued to produce highly finished, detailed scenes drawn from his established repertoire of Middle Eastern and North African subjects.

His commitment to this style, even as artistic tastes began to shift, speaks to his dedication to his chosen genre and the continued market demand for his work. He eventually moved from the bustling center of Paris to the quieter suburb of Fontenay-aux-Roses, where he could continue his work in a more tranquil setting. It was here that he passed away in 1932, at the age of 78, leaving behind a substantial body of work.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Rudolf Ernst's legacy is firmly established within the Orientalist movement. He is remembered as one of its most technically accomplished practitioners, particularly noted for his extraordinary attention to detail, his skillful rendering of textures and light, and his ability to create immersive, atmospheric scenes. Works like The Letter, The Chess Party, and his depictions of mosque interiors remain iconic examples of academic Orientalism.

Historically, Ernst's work, like that of many Orientalists, has been subject to re-evaluation. While admired in his time for their beauty and perceived authenticity, Orientalist paintings came under scrutiny in the later 20th century, particularly following Edward Said's influential critique in his book "Orientalism" (1978). Critics argued that such works often perpetuated stereotypes, presented a romanticized or passive view of Eastern cultures, and served, consciously or unconsciously, the interests of European colonialism by constructing the "Orient" as fundamentally different, exotic, and subordinate to the West.

While acknowledging these valid critiques, art historians today also recognize the artistic merits and historical significance of works by painters like Ernst. His paintings are valued not only for their technical mastery but also as complex cultural documents reflecting 19th-century European attitudes, aesthetics, and interactions with the wider world. They reveal as much about the society that produced and consumed them as they do about the cultures they purport to depict. Ernst's dedication to research and his genuine admiration for the craftsmanship and artistry he encountered on his travels add another layer to the interpretation of his work.

Collections and Enduring Appeal

Today, Rudolf Ernst's paintings are held in numerous public and private collections around the world. Museums with significant holdings of 19th-century European art often include examples of his work. Specialized galleries, such as the Etihad Antique Gallery mentioned in relation to Orientalist art, also feature his paintings, highlighting their continued importance within this specific field. While comprehensive catalogues are challenging for artists whose works are widely dispersed in private hands, records indicate a substantial output, with well over a hundred distinct works documented.

Ernst's paintings continue to command high prices at auction, attesting to their enduring appeal among collectors. The combination of technical virtuosity, exotic subject matter, and decorative quality makes them highly sought after. Furthermore, high-quality reproductions of his most famous works remain popular, allowing a broader audience to appreciate his meticulous visions of the East.

In conclusion, Rudolf Ernst was a pivotal figure in late 19th-century Orientalist painting. From his rigorous training in Vienna to his successful career in Paris, fueled by extensive travels and research, he crafted a distinctive body of work characterized by exquisite detail, rich color, and evocative atmosphere. While viewed through the complex lens of historical and post-colonial critique, his paintings remain compelling examples of artistic skill and potent reflections of the enduring European fascination with the cultures of North Africa and the Middle East. His legacy persists in the collections that preserve his work and in the continued admiration for his masterful technique and captivating subjects.