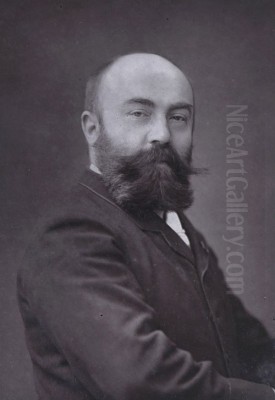

Édouard Frédéric Wilhelm Richter (1844-1913) stands as a notable figure within the French art scene of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Primarily recognized for his contributions to the Orientalist movement, Richter's work navigated the popular tastes and academic traditions of his time, leaving behind a collection of paintings appreciated for their technique and thematic content. His life and career reflect a blend of cultural influences and a dedication to the craft of painting, particularly in capturing scenes inspired by the East, alongside historical subjects and portraiture.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in the Netherlands in 1844, Édouard Richter possessed a mixed European heritage, with a German father and a Dutch mother. This background perhaps contributed to a broader perspective that would later inform his artistic choices. His formal art education began in his birth country, at the esteemed Hague Academy of Art. Seeking to further refine his skills and broaden his horizons, Richter continued his studies in Antwerp, a city with a rich artistic legacy, particularly linked to masters like Peter Paul Rubens.

His ambition ultimately led him to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the nineteenth century. There, he enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the cornerstone of academic art training in France. At the École, Richter had the privilege of studying under two prominent artists and influential teachers: Léon Bonnat and Ernest Hébert. Bonnat was highly regarded for his powerful portraits and realistic style, while Hébert was known for his elegant genre scenes and historical paintings, often with a melancholic or poetic sensibility. Studying under such masters provided Richter with a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and oil painting techniques, aligning him with the academic tradition valued by the official art establishment.

Richter's formal training culminated in his debut at the Paris Salon in 1866. The Salon was the most important art exhibition in the world at that time, and acceptance into it was crucial for any artist seeking recognition and patronage. Successfully exhibiting at the Salon marked Richter's entry into the professional art world of Paris.

Artistic Style and Development

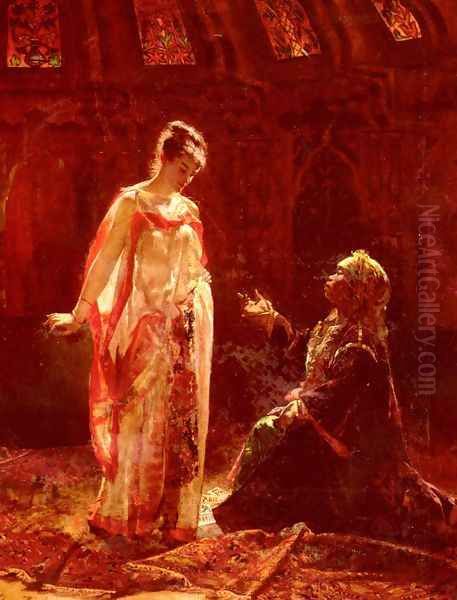

Édouard Richter's artistic output was diverse, encompassing landscapes, portraits, historical subjects, and still lifes. However, he became particularly renowned for his work within the Orientalist genre. Orientalism, a widespread movement in nineteenth-century European art and literature, reflected a deep fascination with the cultures, peoples, and landscapes of North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia—often viewed through a romanticized, exoticizing, or sometimes stereotypical lens. Artists like Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme were leading figures in this genre, and Richter followed in this tradition, contributing his own interpretations of Eastern scenes.

His stylistic journey showed a distinct evolution. Initial works reportedly displayed an influence from the High Renaissance master Raphael, suggesting an early inclination towards classical ideals of harmony, balance, and clarity in form. This points to a solid grounding in academic principles emphasizing drawing and structured composition.

However, Richter's style did not remain static. He later moved towards a freer, more dynamic approach reminiscent of the Baroque era. This shift might imply an embrace of richer colors, more dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and perhaps more energetic brushwork, akin to the style of Baroque masters such as Rembrandt or Rubens, though adapted to nineteenth-century sensibilities.

Ultimately, Richter is said to have developed a unique personal style, synthesizing his academic training, his engagement with past masters like Raphael and the Baroque painters, and his chosen subject matter, particularly Orientalism. This mature style likely combined technical proficiency with a specific atmospheric or narrative quality that distinguished his work.

Themes and Subjects

Orientalism remained a central pillar of Richter's oeuvre. His paintings in this vein likely depicted scenes that catered to the European audience's appetite for the exotic: bustling marketplaces, opulent interiors suggesting harems or palaces, desert caravans, intimate portrayals of figures in traditional attire, or perhaps scenes involving music, dance, or daily life as imagined or observed during travels (though the provided text doesn't specify if he traveled to the East). These works would typically emphasize rich textures, vibrant colors, and detailed settings to evoke a sense of distant lands and cultures.

Beyond Orientalism, Richter engaged with other established genres. His portrait painting, likely influenced by his teacher Léon Bonnat, would have required keen observation and the ability to capture a sitter's likeness and character. Historical painting, another academic staple, allowed artists to depict grand narratives from the past, often with moral or patriotic undertones. Richter's training under Hébert would have prepared him for this genre as well.

The mention of landscape and still life painting indicates a broader artistic practice. His landscapes might have ranged from European scenes to Oriental vistas, while his still lifes would have offered an opportunity to focus purely on form, color, and texture through the arrangement of objects. This versatility demonstrates his comprehensive skill set, honed through his academic education.

Notable Works

Several specific works by Édouard Richter are highlighted, giving a glimpse into his thematic concerns and likely style. Titles such as Studio News and Waiting suggest genre scenes, possibly set in contemporary European or perhaps Orientalist contexts. These titles hint at narratives involving anticipation, communication, or moments of quiet reflection, allowing for psychological exploration of the figures depicted.

The Fortune Teller is a title that strongly aligns with Orientalist or perhaps picturesque European genre themes. Fortune tellers were often depicted as exotic or mysterious figures in nineteenth-century art, fitting well within the romanticized views of other cultures or marginalized groups.

Admiring the Porcelain points towards an interior scene, potentially featuring collectors or connoisseurs, possibly within a European setting or an Orientalist one where porcelain objects might signify exotic trade or refined taste. It suggests a focus on material culture and quiet appreciation.

Femme à la mantille (Woman with a Mantilla) specifically indicates a figure study or portrait featuring a Spanish element – the mantilla. While Spain was sometimes loosely grouped with 'the Orient' in the nineteenth-century imagination due to its Moorish history, this title points more directly to Spanish cultural influence, showcasing Richter's potential interest in various forms of the 'exotic' or picturesque beyond the typical Middle Eastern or North African subjects of Orientalism. The existence of these named works indicates their recognition during his time or in subsequent art historical assessments.

Context and Contemporaries

Édouard Richter operated during a dynamic period in French art. The late nineteenth century saw the dominance of the academic system, centered around the École des Beaux-Arts and the official Salon, where artists like Alexandre Cabanel and Gustave Moreau were influential figures. Richter, through his training and Salon participation, was clearly part of this establishment. His teachers, Bonnat and Hébert, were respected members of this academic world.

However, this was also the era of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Artists like Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were challenging academic conventions and exhibiting independently or in alternative venues, although many initially sought Salon recognition. While Richter's style remained largely within the bounds of academic taste, particularly with his focus on finish and narrative clarity typical of Orientalism, he was working concurrently with these revolutionary movements that were transforming the landscape of modern art.

His specialization in Orientalism placed him alongside other prominent practitioners of the genre, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose highly detailed and often dramatic scenes were immensely popular. Richter contributed to this popular genre, which, despite its problematic aspects from a modern perspective (often perpetuating stereotypes), was a significant and commercially successful part of nineteenth-century European art.

Legacy and Conclusion

Édouard Frédéric Wilhelm Richter's legacy lies primarily in his contribution to French Orientalist painting. His work, characterized by skilled execution learned through rigorous academic training and a stylistic evolution that incorporated influences from historical masters like Raphael and the Baroque painters, found favor within the official art structures of his time, notably the Paris Salon.

His Franco-Dutch-German background adds an interesting dimension to his identity as a French painter. His diverse subject matter, ranging from the popular Orientalist scenes to portraits, historical paintings, landscapes, and still lifes, speaks to his versatility and comprehensive artistic education.

While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries who broke away from the academic mold, Richter represents a significant strand of late nineteenth-century art that focused on narrative, exoticism, and technical polish. His works, such as The Fortune Teller and Femme à la mantille, continue to be recognized as representative examples of his style and thematic interests, securing his place within the history of French art and the enduring, complex tradition of Orientalism. His career exemplifies the path of a successful artist working within the established systems of the era, contributing skilled and engaging works to the genres he pursued.