Eugène Alexis Girardet stands as a significant figure within the French Orientalist movement of the late 19th century. Born into a world captivated by the perceived exoticism of North Africa and the Middle East, Girardet dedicated much of his artistic career to capturing the landscapes, people, and daily life of these regions. His work, characterized by a keen eye for detail, a masterful handling of light, and a sensitivity to atmosphere, offers a valuable window into both the subjects he depicted and the European fascination with the "Orient" during his time. He navigated the artistic currents of his era, absorbing lessons from academic tradition while forging a personal style deeply influenced by his direct experiences abroad.

An Artistic Heritage and Formative Years

Eugène Alexis Girardet was born in Paris on May 31, 1853, into a family already steeped in artistic tradition. His Swiss-descended family boasted several generations involved in the arts, particularly engraving, painting, and lithography. His father, Paul Girardet, was himself a respected engraver and printmaker, ensuring that young Eugène grew up in an environment where artistic skill was valued and nurtured. This familial background undoubtedly provided him with an early exposure to visual arts and technical skills.

Showing remarkable precocity, Girardet reportedly began selling his own artworks by the age of seventeen. This early success hinted at the talent that would define his career. Seeking formal training to hone his abilities, he enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. This institution was the bedrock of academic art training in France, emphasizing drawing, composition, and the study of historical and classical models.

Crucially, Girardet studied under the tutelage of Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904). Gérôme was one of the most famous and influential academic painters of his time, renowned not only for his historical and mythological scenes but also for his own highly detailed and popular Orientalist works. Gérôme's interest in the Middle East and North Africa, fueled by his own travels, profoundly impacted his students, and Girardet was no exception. The master's emphasis on meticulous detail, polished finish, and dramatic or ethnographic subject matter provided a strong foundation for Girardet's own artistic explorations.

The Lure of the East: Journeys of Discovery

The defining turn in Girardet's artistic path came with his travels. Following in the footsteps of his mentor Gérôme and other pioneering artists like Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) and Eugène Fromentin (1820-1876), Girardet felt the pull of lands perceived as vastly different from Europe. In 1874, he embarked on his first journey to North Africa. This initial voyage marked the beginning of a lifelong fascination with the region.

Over the subsequent years, Girardet made numerous trips, venturing into Morocco, Spain (often a gateway or related destination for Orientalist painters), Tunisia, and, significantly, Algeria. He also traveled to Egypt, another key location within the Orientalist imagination. These journeys were not mere tourist excursions; they were immersive experiences that provided the raw material for his art. He sketched, observed, and absorbed the unique quality of light, the vibrant colors, the textures of the landscapes, the architecture, and the customs of the people he encountered.

Algeria, in particular, seems to have held a special significance for him. He spent considerable time there, exploring not just the coastal cities but also venturing into the desert regions, such as the areas around Biskra and El Kantara, which also attracted other artists. These locales offered dramatic scenery and insights into the lives of nomadic peoples, subjects that would feature prominently in his work. His travels provided an authenticity and specificity that distinguished his paintings.

A significant encounter occurred around 1877 when Girardet met Étienne Dinet (1861-1929). Dinet, who would later convert to Islam and become known as Nasreddine Dinet, was another French painter deeply committed to depicting Algerian life with ethnographic accuracy and empathy. This meeting likely reinforced Girardet's own move away from purely academic renditions towards a style more focused on capturing the lived reality and specific cultural details of North Africa, albeit still through a European lens.

Artistic Style: From Academic Roots to Orientalist Vision

Girardet's artistic style evolved throughout his career, shaped by his training, his travels, and his engagement with contemporary art movements. His early works, such as Café Arabe, show the clear influence of his academic training under Gérôme. These pieces often exhibit a precise realism, careful composition, and a relatively controlled palette, focusing on clear narrative or genre scenes.

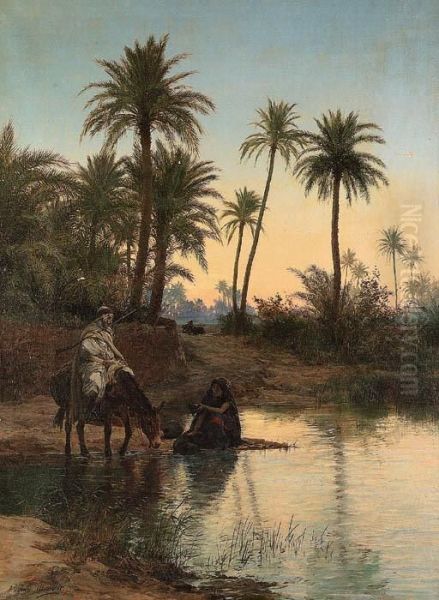

However, his repeated immersion in the North African environment led to a noticeable shift. The intense sunlight, the vibrant colors of local textiles and markets, and the textures of the desert and architecture began to permeate his canvases. His brushwork potentially became somewhat looser, and his palette brightened considerably as he sought to capture the unique atmospheric effects of the region. While maintaining a strong foundation in drawing and realistic representation, his work gained a greater emphasis on ethnographic detail and conveying the feeling of a place.

He became particularly adept at rendering the dazzling North African light and its effects on surfaces and figures. Whether depicting the cool shadows of a narrow street, the bright glare of the desert sun, or the warm glow of an interior, Girardet used light to create mood, define form, and enhance the sense of place. This sensitivity to light aligns him with the broader concerns of many 19th-century painters, though he generally remained distinct from the Impressionists like Claude Monet (1840-1926) or Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), retaining a greater focus on narrative and detailed rendering.

His style can be firmly placed within Orientalism, the 19th-century European artistic and cultural movement fascinated with the East. Like many Orientalists, his work often blended realistic observation with a degree of romanticization. He depicted scenes of daily life, bustling markets, quiet moments of prayer, desert caravans, and intimate domestic settings. While striving for accuracy in details of costume, architecture, and custom, his compositions often emphasized the picturesque or the perceived exoticism of his subjects, catering to the tastes of his European audience.

Major Themes and Representative Works

Girardet's oeuvre revolves around several recurring themes, primarily drawn from his North African experiences. The desert landscape, with its vastness, its unique light, and the nomadic life it sustained, was a major source of inspiration.

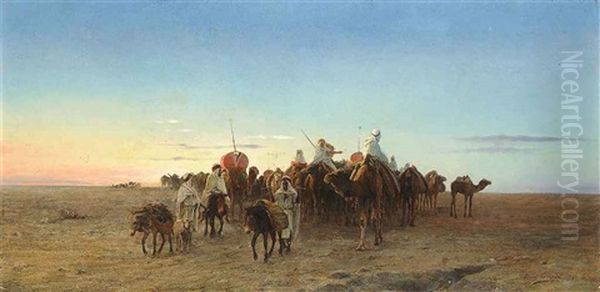

Desert Life and Nomads: Paintings depicting caravans traversing the sands, Bedouin encampments, and solitary figures against the expansive desert backdrop are common. Works like Prayer in the Desert or Life of the Nomads (titles may vary) capture the perceived austerity and spiritual dimension of desert existence. These scenes often highlight the resilience of life in a harsh environment and play into European ideas about the timeless nature of the desert peoples.

Marketplaces and Urban Scenes: The vibrant energy of North African towns and cities provided another rich vein of subject matter. The Souk (or The Market) is a representative example, showcasing Girardet's ability to depict bustling crowds, diverse activities, and the interplay of light and shadow in narrow, covered marketplaces. These works allowed him to explore local commerce, social interactions, and the colorful details of urban life.

Daily Life and Genre Scenes: Girardet often focused on intimate scenes of everyday activities. Les Enfants des fabricants de chaussures (Children of the Shoemakers) exemplifies this interest. Such works provide glimpses into domestic interiors or workshops, focusing on family life, craftspeople, or quiet moments. They often carry an ethnographic interest, documenting clothing, tools, and social customs.

Religious Themes: Scenes of prayer, both individual and communal, appear in his work, reflecting the importance of Islam in the regions he visited. Árabe em prece (Arab in Prayer, 1888) is one such example. These paintings often emphasize the devotion and spirituality of the subjects, sometimes framed by dramatic architectural settings or landscapes.

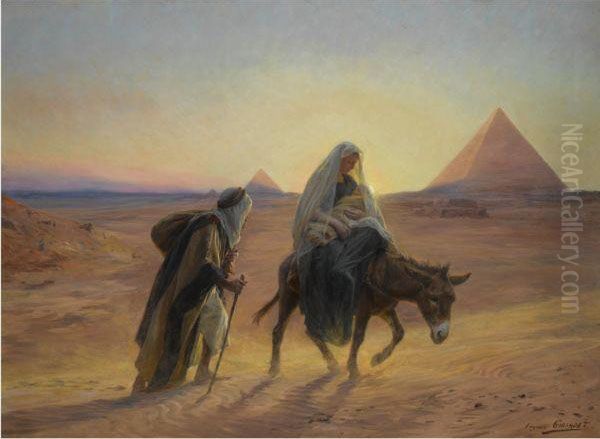

Biblical Scenes in Oriental Settings: One of Girardet's most famous works is Flight into Egypt. This painting takes a traditional Christian narrative – the Holy Family's escape from Herod – and transposes it into a meticulously rendered North African desert landscape, likely based on his direct observations in Egypt or Algeria. The work combines religious storytelling with his signature Orientalist style, showcasing his skill in landscape, figure painting, and atmospheric effect. This painting was well-received and has appeared at auction multiple times, attesting to its enduring appeal.

Other notable works mentioned include Café Arabe, Souvenirs d'été (Summer Memories), and Our Wagon is Moving, further illustrating the range of his Orientalist subjects, from relaxed social settings to scenes of travel and perhaps nostalgia.

Girardet Among Contemporaries: Influence and Association

Eugène Girardet operated within a vibrant and complex art world. His primary mentor, Jean-Léon Gérôme, remained a towering figure in academic and Orientalist art throughout Girardet's formative years. Gérôme's studio was a hub, producing numerous artists interested in similar themes.

Girardet's encounter with Étienne Dinet was significant, suggesting a collegial relationship among artists drawn to similar subjects, potentially sharing insights and approaches. The broader field of French Orientalism included many other notable painters during his time, creating a context of shared interests, potential rivalries, and mutual influences. Figures like Gustave Guillaumet (1840-1887), known for his empathetic depictions of Algerian life, Léon Belly (1827-1877), celebrated for his detailed Egyptian scenes, Alberto Pasini (1826-1899), an Italian painter active in Paris known for his Constantinople and Persian subjects, and the American Frederick Arthur Bridgman (1847-1928), another Gérôme pupil who specialized in North African scenes, were all part of this landscape.

While direct evidence of specific collaborations or intense rivalries with these figures might be scarce in the provided snippets, Girardet was clearly part of this milieu. His involvement in founding the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français (Society of French Orientalist Painters) in 1893 (though some sources suggest earlier roots or related activities around 1877) is crucial. Often credited as being established under the leadership of Léonce Bénédite, the society aimed to promote Orientalist art, organize dedicated exhibitions, and foster a sense of community among artists working in this genre. Girardet's role as a co-founder underscores his commitment to Orientalism and his standing among his peers. This society provided a platform distinct from the main Paris Salon, highlighting the growing specialization and popularity of Orientalist themes.

Beyond the Orientalist circle, Girardet's work existed alongside other major currents in French art. The Impressionists were revolutionizing landscape and modern life painting, while academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905) continued to achieve immense success with mythological and idealized genre scenes. Landscape painters associated with the Barbizon school, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875) and perhaps Paul Huet (1803-1869) mentioned in the source material (though their direct connection to Girardet seems minimal), represented an earlier generation's focus on naturalism. Girardet carved his niche by applying academic precision to exotic subjects, infused with the light and color observed during his travels.

He also engaged in activities beyond easel painting. His advice on engravings for the Voyage en Tunisie project, involving historian Henri Saladin and architect René Cagnat, shows an engagement with other forms of artistic production and historical documentation related to North Africa.

Later Career, Recognition, and Legacy

Eugène Girardet continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life. He regularly submitted works to the Paris Salon, the main venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage. His participation in the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (joining in 1890) indicates his integration into the established art institutions of Paris.

His work was also showcased at major international events, including the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1900 and the Exposition Coloniale (Colonial Exhibition) in Marseille in 1906. These exhibitions were significant platforms, reflecting both artistic trends and the broader political context of French colonialism, which was intertwined with the popularity of Orientalist art. His paintings were exhibited not only in Paris but also internationally, including in London and Geneva, indicating a reach beyond France.

Girardet passed away in Paris on May 5, 1907, leaving behind a substantial body of work dedicated to his vision of the Orient. His paintings captured the imagination of his contemporaries and continue to be sought after by collectors and institutions today. His works are held in various museum collections, including potentially the Louvre or Musée d'Orsay in Paris (which houses many 19th-century works) and the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Marseille, among others.

His legacy lies in his contribution to the Orientalist genre. He stands as a painter who moved beyond second-hand depictions, grounding his art in direct observation during extensive travels. While viewed through the lens of his time – a perspective that modern critics might analyze for its colonial undertones and potential romanticization – his work is valued for its technical skill, particularly the rendering of light and atmosphere, its detailed ethnographic observation, and its evocative portrayal of North African life and landscapes. He remains a key representative of that generation of European artists who sought inspiration and subject matter in the lands across the Mediterranean.

Conclusion: A Painter of Light and Place

Eugène Alexis Girardet dedicated his artistic life to translating the vibrant realities and perceived romance of North Africa and the Middle East onto canvas. Born into an artistic family and trained under a master of academic and Orientalist painting, he absorbed the techniques of his time but found his true voice through extensive travel and direct observation. His journeys provided him with a wealth of subjects – the sun-drenched deserts, the bustling souks, the quiet moments of daily life and prayer – which he rendered with meticulous detail and a remarkable sensitivity to light and color.

As a co-founder of the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français, he played a role in consolidating and promoting this popular genre. His works, from the famous Flight into Egypt to intimate genre scenes like Children of the Shoemaker, reflect both a commitment to realistic depiction and the romantic allure that the "Orient" held for 19th-century Europeans. While part of a broader movement, Girardet developed a recognizable style that continues to engage viewers with its blend of ethnographic interest, atmospheric beauty, and narrative charm. He remains an important figure for understanding the complexities of Orientalist art and the enduring European fascination with the cultures he depicted.