William Daniell (1769-1837) stands as a significant figure in the annals of British art, celebrated primarily as a landscape and marine painter, but also highly accomplished as a printmaker, particularly in the medium of aquatint, and as a watercolourist. Born in Kingston upon Thames, Surrey, England, his life and career were marked by extensive travels, meticulous observation, and the creation of monumental works that documented the landscapes and cultures of both the Indian subcontinent and the coastlines of Great Britain. His election as a Royal Academician (RA) cemented his status within the British art establishment, and his works continue to be valued for their artistic merit and historical significance.

Daniell's origins were relatively modest. His father was a bricklayer who also managed an inn called "The Swan" in Chertsey, near Kingston upon Thames. The course of young William's life changed dramatically following his father's death. Around 1779, he was taken under the wing of his uncle, Thomas Daniell (1749-1840), who was himself an aspiring painter. This move proved pivotal, setting William on the path to an artistic career under the direct tutelage of his elder relative.

Early Life and the Call of the East

Under Thomas Daniell's guidance, William received his initial artistic training. Thomas, though not yet widely established, recognized the potential for artists in the expanding British Empire, particularly in India. The allure of the East, with its exotic landscapes, ancient architecture, and different cultures, presented a tantalizing prospect for an artist seeking novel subjects and patronage. The late 18th century saw a growing European fascination with 'Oriental' scenes, fueled by travelogues and the activities of the East India Company.

In 1784 or 1785 (sources slightly vary, but 1785 is commonly cited for their departure), Thomas Daniell secured permission from the East India Company to travel to Calcutta (now Kolkata) as an engraver. He decided to take his young nephew, William, then only about fourteen or fifteen years old, along as his assistant. This decision launched one of the most remarkable artistic partnerships and journeys of the era. William's role was initially to help his uncle, but the experience would profoundly shape his own artistic development and provide the raw material for their most famous collaborative project.

The Indian Odyssey (with Thomas Daniell)

The Daniells arrived in Calcutta via China in early 1786. Their timing coincided with a period of relative stability under Governor-General Cornwallis, which facilitated travel within parts of the subcontinent. They remained in India for approximately seven years, finally departing for England in 1794. This extended period allowed them to undertake extensive and often arduous journeys far beyond the confines of Calcutta, venturing through northern and southern India.

Their travels took them up the Ganges river to cities like Murshidabad, Bhagalpur, Patna, Varanasi (Benares), Allahabad, Kanpur (Cawnpore), and Agra, where they marvelled at Mughal architecture including the Taj Mahal. They journeyed overland towards Delhi and into the Garhwal region of the Himalayas, sketching landscapes and temples. Later, they travelled south, visiting Madras (now Chennai), Mysore, and various sites along the Coromandel Coast, documenting rock-cut temples, forts, and dramatic natural scenery.

Throughout these travels, both Thomas and William were constantly sketching and painting. William, initially an assistant learning the ropes, rapidly developed his skills in watercolour and drawing. They employed a camera obscura to aid in achieving topographical accuracy in their initial sketches. This device projected an image of the scene onto a surface, which could then be traced, ensuring correct perspective and proportion – crucial for the detailed architectural and landscape views they aimed to produce. Their journey was not without hardship, involving difficult terrain, challenging climates, and the logistical complexities of moving through regions sometimes affected by conflict or instability.

They were not the first European artists in India; painters like Tilly Kettle (1735-1786) and Johann Zoffany (1733-1810) had already worked there, primarily focusing on portraits of British officials and Indian rulers, although Zoffany also produced some notable conversation pieces and scenes of Indian life. However, the Daniells' project was unprecedented in its systematic focus on landscape and architecture across such a vast geographical area, and in its intention to translate these findings into a major print series upon their return.

Oriental Scenery: A Monumental Work

Upon returning to England in 1794, the Daniells embarked on the monumental task of translating their vast collection of sketches and watercolours into finished works for publication. The result was Oriental Scenery, a series published in six parts between 1795 and 1808, comprising a total of 144 hand-coloured aquatint prints. This ambitious project became one of the most celebrated and influential illustrated books of the period.

Aquatint was the chosen medium, perfectly suited for capturing the tonal variations of their watercolour sketches and rendering the effects of light and atmosphere on Indian landscapes and architecture. This intaglio printmaking technique uses acid to etch a plate coated with porous resin, creating areas of tone rather than just lines. The Daniells became masters of this process, achieving remarkable subtlety and richness in their prints. William played a crucial role in the aquatinting process, developing considerable expertise.

Oriental Scenery presented British audiences with breathtaking and meticulously detailed views of India's most famous monuments – temples, mosques, forts, palaces – alongside depictions of its diverse landscapes, from Himalayan foothills to southern coastal scenes. The work was a commercial and critical success. It catered to the burgeoning interest in the picturesque and the exotic, offering a vision of India that was both informative and aesthetically pleasing. It significantly shaped British perceptions of the subcontinent, providing a visual vocabulary for understanding its ancient civilizations and natural beauty.

The publication cemented the reputations of both Thomas and William Daniell. While Thomas was the senior partner, William's contribution, particularly in the execution of the aquatints and likely in many of the original field sketches, was substantial. The work remains a vital historical record, documenting sites before subsequent changes and offering insights into the colonial encounter, presenting India through a specific, albeit often romanticized, European lens. Its influence extended to architecture and design in Britain, contributing to the taste for 'Indian' motifs.

Return to England and Academic Recognition

Back in London, William Daniell sought to establish his independent artistic identity while continuing to collaborate with his uncle on the Oriental Scenery project. He enrolled at the Royal Academy Schools in 1799, perhaps seeking to formalize his training and engage more fully with the London art world after his extensive practical experience abroad. This was the preeminent institution for art education and exhibition in Britain, founded under the patronage of King George III with Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) as its first president, later succeeded by Benjamin West (1738-1820).

Daniell began exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions, as well as at the British Institution, another important venue. His exhibited works included oil paintings and watercolours based on his Indian travels, but increasingly also featured British subjects, particularly coastal and marine scenes. His skill and growing reputation were recognized by his peers. In 1807, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA).

Full membership as a Royal Academician (RA) followed in 1822. This was a significant honour, placing him among the elite of the British art world, alongside contemporaries like the landscape giants J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) and John Constable (1776-1837), although Daniell's style remained distinct, generally favouring topographical accuracy over the more expressive or atmospheric approaches often associated with Romanticism. Election to the RA signified high professional standing and provided further opportunities for exhibition and influence.

Mastering Watercolour and Aquatint

William Daniell's technical proficiency was central to his success. He was a highly skilled watercolourist, capable of capturing delicate effects of light and atmosphere while maintaining clarity and detail. Watercolour painting was undergoing a "golden age" in Britain during his lifetime, with artists like Thomas Girtin (1775-1802), John Sell Cotman (1782-1842), David Cox (1783-1859), and Peter De Wint (1784-1849) elevating the medium's status. Daniell contributed to this development, particularly through the translation of watercolour aesthetics into print.

His mastery of aquatint was perhaps even more distinctive. While Paul Sandby (1731-1809) is often credited with popularizing the technique in Britain for topographical views, the Daniells, particularly through Oriental Scenery, demonstrated its potential on an unprecedented scale and level of sophistication. William's subsequent solo projects further showcased his command of the medium. Aquatint allowed him to reproduce the subtle washes and tonal gradations of his watercolours, making high-quality, coloured landscape prints accessible to a wider audience than unique paintings.

His process typically involved making detailed pencil sketches and often watercolour studies directly from nature during his travels. Back in his London studio, he would work these up into finished watercolours or oil paintings, and crucially, translate them into aquatint plates. This combination of fieldwork and studio refinement ensured both accuracy and artistic finish. The hand-colouring of the aquatint prints was usually done by teams of colourists following a master copy, adding vibrancy and appeal.

Embarking on A Voyage Round Great Britain

Following the completion of Oriental Scenery and having established himself within the London art scene, William Daniell conceived another ambitious project, this time focusing on his native land. Between 1814 and 1825, he undertook a series of summer voyages around the coastline of Great Britain, starting from Land's End in Cornwall and travelling clockwise, eventually reaching Penzance again after circumnavigating the mainland, including extensive exploration of the Scottish coast and islands.

This undertaking, A Voyage Round Great Britain, was arguably even more demanding logistically than the Indian journey, involving navigating often treacherous coastal waters in small vessels and sketching in all kinds of weather. The timing was significant; the Napoleonic Wars had restricted foreign travel for Britons, fostering a greater interest in domestic tourism and scenery. Daniell aimed to create a comprehensive visual record of the entire coastline, its harbours, towns, castles, and natural features.

The project resulted in a publication issued in eight volumes between 1814 and 1825 by the publishers Longman & Co. It contained a staggering 308 hand-coloured aquatint plates, all based on Daniell's own drawings made during his travels. The accompanying text was initially written by Richard Ayton, who travelled with Daniell for the first part of the journey, but Daniell himself took over the writing for the later volumes after Ayton withdrew.

The British Coastline Unveiled

A Voyage Round Great Britain is considered one of the finest colour-plate books ever produced. Its scope is remarkable, offering an unparalleled visual survey of the British coast as it appeared in the early 19th century, before the dramatic changes brought by railways and industrialization. Daniell's plates capture the diversity of the coastline, from the busy ports of Liverpool and Bristol to the remote cliffs of Scotland and the picturesque fishing villages of Cornwall.

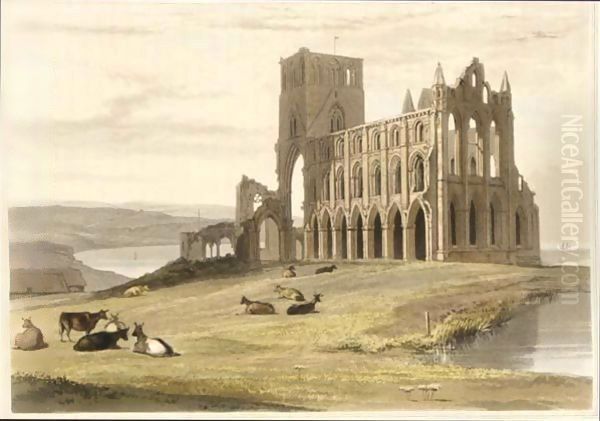

His commitment to topographical accuracy is evident throughout. He meticulously recorded details of geology, architecture, shipping, and human activity. Views of places like Whitby Abbey perched on its cliff, the bustling harbour of Scarborough, the unique structure of Deal Castle, or the dramatic scenery of the Scottish Highlands and Islands are rendered with clarity and precision. Yet, his work often transcends mere documentation, capturing the atmosphere and unique character of each location.

The Voyage aligns with the contemporary interest in the "Picturesque," an aesthetic category popularized by writers like William Gilpin (1724-1804), which valued scenery that was varied, irregular, and visually interesting, often with a touch of wildness or decay. Daniell's coastal views frequently embody these qualities. The publication was well-received and remains an invaluable resource for historians, geographers, and anyone interested in the maritime heritage and landscape history of Britain. It stands as a testament to Daniell's endurance, artistic skill, and dedication to large-scale topographical projects.

Artistic Style: Precision and Atmosphere

William Daniell's artistic style is characterized by a commitment to accuracy and clarity, combined with a sensitive handling of light and colour. Whether working in watercolour, oil, or translating his views into aquatint, he prioritized detailed representation of topography and architecture. This precision gives his work immense documentary value. Compared to some of his more overtly Romantic contemporaries like Turner, Daniell's landscapes are generally calmer and more objective, though certainly not devoid of atmosphere or aesthetic appeal.

His compositions are carefully constructed, often using classical framing devices but adapted to the specific landscape. His rendering of water, skies, and geological formations is particularly adept. In his aquatints, the skillful use of tonal variation creates a convincing sense of depth and form, while the hand-colouring adds vibrancy and local character. Even within the constraints of topographical art, Daniell found ways to convey the mood of a place, whether the bustling energy of a port or the quiet solitude of a remote bay.

His work reflects the scientific curiosity of the age, an Enlightenment desire to observe, classify, and record the world. Yet, it also participates in the growing appreciation for landscape as a subject worthy of serious artistic attention, a trend seen in the work of earlier figures like Richard Wilson (c. 1714-1782) and Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788) in his landscape drawings and paintings, and reaching full fruition with Constable and Turner. Daniell carved his own niche within this tradition, focusing on the detailed, comprehensive survey rendered through the reproducible medium of aquatint.

Collaborations and Connections

The most significant collaboration of William Daniell's career was undoubtedly with his uncle, Thomas Daniell. Their Indian journey and the production of Oriental Scenery were joint efforts that shaped both their careers. While William eventually established his independent reputation, the foundational experience with Thomas was crucial.

Beyond his uncle, direct artistic collaborations seem less prominent in William's later career, especially on major projects like the Voyage. However, he operated within a vibrant London art world. As an RA, he was part of an institution that included many leading artists of the day. He would have known and exhibited alongside painters like Turner, Constable, Sir Thomas Lawrence (portraitist, 1769-1830), and sculptors like Sir Francis Chantrey (1781-1841).

His influence extended to later artists. The text mentions the architect David Addey revisiting and painting Daniell's Voyage locations, consciously following in his footsteps. His prints also provided source material and inspiration for numerous other artists and illustrators. While perhaps not as stylistically influential as Turner or Constable, his dedication to large-scale topographical print projects set a high standard. His work can also be seen in relation to other printmakers and illustrators of the era, such as Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) or Augustus Pugin (1762-1832), who also documented aspects of British life and architecture, albeit often with different stylistic aims (Rowlandson's satirical edge, Pugin's architectural focus). Engravers like William Woollett (1735-1785) had earlier set high standards for landscape engraving, a tradition Daniell adapted to aquatint.

Legacy and Historical Significance

William Daniell's legacy rests primarily on his two monumental print series, Oriental Scenery and A Voyage Round Great Britain. These works secured his contemporary fame and remain his most enduring achievements. They represent landmarks in the history of colour-plate books and the use of aquatint for topographical and landscape subjects.

His contribution to the visual record of both India and Britain in the late 18th and early 19th centuries is immense. Oriental Scenery played a key role in constructing the European image of India, while the Voyage provides an invaluable, comprehensive snapshot of the British coastline before the transformative impact of the Industrial Revolution and modern development. His dedication to accuracy makes his work a vital resource for historical study.

As an artist, he demonstrated exceptional skill in watercolour and mastery of the aquatint process. His election as a Royal Academician confirms his standing within the art establishment of his time. While sometimes overshadowed by the more revolutionary figures of Romanticism, Daniell's meticulous observation, technical brilliance, and the sheer ambition and scope of his projects guarantee his place in British art history. His works are held in major collections worldwide, including the Royal Academy of Arts, the British Library, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Maritime Museum in London, and the Yale Center for British Art, attesting to their lasting importance.

Conclusion

William Daniell RA was an artist defined by diligence, technical mastery, and an adventurous spirit. From his formative journey through India with his uncle Thomas, resulting in the landmark Oriental Scenery, to his ambitious solo circumnavigation and documentation of the British coast in A Voyage Round Great Britain, his career was dedicated to observing and recording the world around him with remarkable precision and artistry. As a leading exponent of aquatint and a fine watercolourist, he created works that were not only aesthetically pleasing but also of profound historical and topographical value. He provided his contemporaries, and posterity, with unique visual windows onto the landscapes and cultures of the East and the shores of his homeland, securing his reputation as a master chronicler in print.