Samuel Howitt stands as a significant figure in British art of the late Georgian period, celebrated primarily for his vibrant and detailed depictions of animals, sporting pursuits, and the natural world. Active as a painter, watercolourist, illustrator, and etcher, Howitt captured the energy and spirit of country life and exotic wildlife with a distinctive flair. Born into the landed gentry but driven by financial necessity to pursue art professionally, he brought an insider's knowledge and passion to his subjects, creating a body of work that remains highly valued for its artistic merit and historical insight.

From Country Gentleman to Professional Artist

Samuel Howitt was born around 1756 or 1757, likely in Nottinghamshire, into a prosperous Quaker family with established roots. The Howitts were country squires, holding land in Chigwell, Essex, which provided young Samuel with an upbringing steeped in the traditions and pastimes of the rural gentry. From an early age, he developed a profound love for the outdoors and field sports, becoming an enthusiastic participant in hunting, fishing, and horse racing. This intimate, firsthand experience would prove foundational to his later artistic career.

Initially, Howitt pursued his artistic inclinations as an amateur, a gentleman painter indulging a passion rather than seeking a livelihood. However, shifts in the family's financial fortunes compelled him to turn his talent into a profession. This transition marks a fascinating aspect of his biography – a member of the landed class entering the commercial art world, driven not by choice but by circumstance. He appears to have been largely self-taught, honing his skills through observation and practice rather than formal academic training.

Around 1779, Howitt made the pivotal move to London, settling in the West End to establish himself within the city's bustling art scene. He began working professionally as both a painter and a printmaker, seeking recognition and patronage. His deep familiarity with his subjects, combined with a natural artistic ability, quickly gained attention.

Early Exhibitions and Recognition

Howitt began exhibiting his work publicly in the early 1780s. Records show him presenting three coloured drawings with hunting themes at the Incorporated Society of Artists in 1783. This marked his formal entry into the London exhibition world. The following year, in 1784, he began a long association with the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts, exhibiting the first of many works there. His submissions frequently featured the sporting scenes and animal studies that would become his trademark.

Throughout the 1780s, 1790s, and into the early 19th century, Howitt was a regular contributor to the Royal Academy's annual exhibitions. Notable works displayed included Jaques and the Deer (1793), Smugglers Alarmed (1794), Dead Game (1814), and Bella, horrida Bella (1815). These titles reflect the range of his interests, from literary references (Shakespeare's As You Like It in the first example) to contemporary genre scenes and classic still life subjects, all infused with his characteristic attention to natural detail. His consistent presence at the RA helped solidify his reputation among fellow artists and potential patrons.

Artistic Style: Vitality and Observation

Howitt's artistic style is characterized by its energy, immediacy, and keen observation, particularly of animals in motion. He worked proficiently in both oil and watercolour, but it is perhaps in the latter medium, often combined with pen and ink outlines, that his distinctive qualities shine most brightly. His watercolours possess a freshness and spontaneity, using clear washes of colour to capture light and form. The underlying drawing often remains visible, contributing to the sense of liveliness.

His approach differed from some of his contemporaries. While artists like George Stubbs brought an almost scientific, anatomical precision to their animal portraits, Howitt's focus was more on capturing the spirit and movement of the creature within its environment. His animals are rarely static; they leap, run, fight, and hunt across his compositions. This dynamism likely stemmed directly from his own experiences in the field, observing animals in their natural state during hunts or while exploring the countryside.

Compared to the often more rustic or sentimental scenes of his contemporary George Morland, Howitt's work generally maintained a clearer focus on the action of the sport or the specific characteristics of the animal. His linework, particularly in his drawings and etchings, shows an affinity with the fluid, expressive lines of his famous brother-in-law, the caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson, though Howitt applied this energy to natural history rather than social satire.

Master of Etching

Beyond his paintings and watercolours, Samuel Howitt was a highly accomplished and prolific etcher. He embraced printmaking not just as a means of reproducing his designs but as an expressive medium in its own right. His etchings often closely mirrored the style of his drawings, featuring vigorous, confident lines that effectively conveyed texture and movement – the rough coat of a hound, the sleek feathers of a game bird, the tension of a predator stalking its prey.

He produced numerous sets of etchings, often published under titles like Miscellaneous Etchings, Old and New or as illustrations for various sporting publications. His skill extended to different etching techniques, possibly including soft-ground etching, which could replicate the tonal qualities of drawing. These prints made his work accessible to a wider audience and were instrumental in disseminating his images of British wildlife and sporting life. His contribution to British printmaking, particularly in the realm of natural history and sporting subjects, is significant, placing him alongside other skilled etchers of the period, though his focus remained distinct from the political satire of James Gillray or the visionary work of William Blake.

Themes: The British Sporting Life

The heart of Howitt's oeuvre lies in his depiction of British field sports. Having grown up participating in these activities, he possessed an intimate understanding of their rituals, excitement, and technical details. His works cover the full spectrum of country pursuits favoured by the gentry of his time: fox hunting, stag hunting, hare coursing, shooting (grouse, pheasant, partridge), and angling.

His hunting scenes are particularly noteworthy for their sense of action and narrative. He captured the thrill of the chase – hounds in full cry, horses leaping fences, the fox breaking cover. He understood the relationship between the participants – human and animal – and depicted the landscape not merely as a backdrop but as an active element of the pursuit. Works like those illustrating The British Sportsman series exemplify his ability to convey the energy and atmosphere of these events.

His fishing scenes, such as those illustrating The Angler's Manual, demonstrate a quieter but equally observant approach. He depicted the patience of the angler, the specific types of fish, and the tranquil beauty of riverside settings. Through these works, Howitt provided a comprehensive visual record of the sporting culture of Georgian England, a culture deeply intertwined with the social life of the countryside. His contemporaries in this field included established masters like George Stubbs and Sawrey Gilpin, as well as Philip Reinagle and the slightly younger James Ward, each bringing their own perspective to the genre.

Themes: A Fascination with Animals

Howitt's passion for sport was inseparable from his fascination with animals, both domestic and wild. His portfolio is a veritable menagerie of British fauna. He depicted horses with an understanding of their power and grace, essential for his racing and hunting scenes. Dogs, particularly hounds and gun dogs, were rendered with attention to breed characteristics and working postures. He painted deer, foxes, hares, and game birds with an accuracy born of close observation.

His interest extended beyond the typical subjects of sporting art. He produced studies of farm animals and seemed particularly drawn to depicting predators and moments of natural conflict. It is known that artists of the time often studied animals at menageries, such as the famous collection at the Tower of London, and it is likely Howitt availed himself of such opportunities to observe creatures less commonly encountered in the British countryside.

One significant publication highlighting his focus on animals is A New Work of Animals, Principally Designed from the Fables of Aesop, Gay, and Phaedrus (1811). This collection of 56 plates showcased his ability to imbue animal subjects with character and narrative weight, drawing inspiration from classical and contemporary literary sources. These works demonstrate not only his skill in animal draughtsmanship but also his engagement with the allegorical tradition, using animals to comment on human nature. His dedication to animal portrayal places him firmly within a lineage of British animal artists stretching back to Francis Barlow in the 17th century and continuing through Stubbs, Gilpin, and Ward.

Themes: Visions of India - Oriental Field Sports

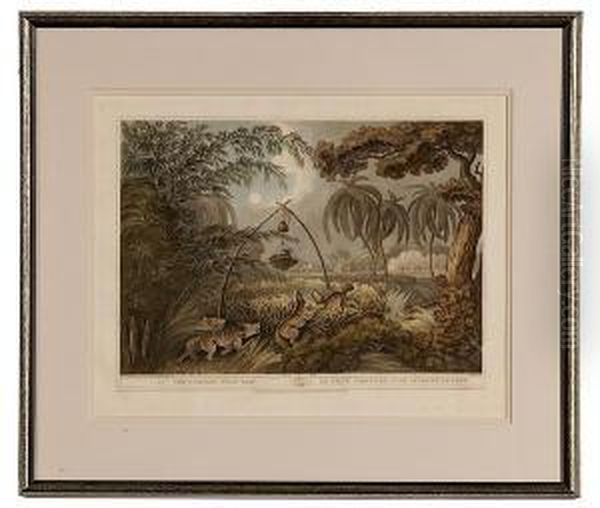

Perhaps Howitt's most celebrated single project is his set of illustrations for Captain Thomas Williamson's Oriental Field Sports, published in 1807 by Edward Orme. This lavish publication featured forty large, coloured aquatints based on Williamson's original sketches made during his time in British India. While Williamson provided the initial compositions and expert knowledge of the Indian context, Howitt's artistic skill transformed these sketches into dramatic and compelling images.

The plates depict a wide array of hunting activities unique to the subcontinent, including tiger hunting from elephant-back, cheetahs hunting deer, hog hunting, and encounters with rhinoceroses and buffaloes. Howitt vividly captured the exotic landscapes, the vibrant attire of the participants, and the dramatic intensity of these often dangerous pursuits. He successfully conveyed the scale and power of animals like elephants and tigers, creatures far removed from his native British wildlife.

Oriental Field Sports was immensely popular and remains a landmark work in the history of sporting books and depictions of British India. It offered audiences in Britain a thrilling glimpse into the life of Englishmen in the colonies and the spectacular wildlife of the East. The success of this project cemented Howitt's reputation as a versatile artist capable of tackling subjects beyond the familiar British scene.

Major Publications and Illustrations

Samuel Howitt's career was significantly intertwined with the publishing world. His skills as an illustrator and etcher were in high demand for books and periodicals catering to the growing interest in sport, natural history, and travel. Beyond the major works already discussed (Oriental Field Sports, A New Work of Animals, The British Sportsman), he contributed to numerous other publications.

He was a long-time illustrator for The Sporting Magazine, a highly popular periodical founded in 1792 that covered all aspects of sporting life. His plates appeared regularly, bringing current events like race meetings and notable hunts to a wide readership. He also illustrated works like The Angler's Manual; or, Concise Lessons of Experience (1808) and produced standalone sets of prints like British Preserve (1824, possibly posthumous).

His collaborations involved various publishers, including Edward Orme, Thomas McLean, Rudolph Ackermann (a major publisher of illustrated books, including many by Rowlandson), S. Bagster, and his own relative, Thomas Williamson, who ran a print shop. This extensive work in illustration ensured that Howitt's images reached a broad audience and played a significant role in shaping the visual culture surrounding sport and natural history in his era.

Contemporaries and Connections

Howitt operated within a vibrant London art world, interacting with numerous other artists, engravers, and publishers. His most significant personal and professional connection was undoubtedly with Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827). Howitt married Rowlandson's sister, Elizabeth. While sources suggest the marriage may not have been entirely happy, leading to periods of separation, the familial tie fostered a close artistic relationship. There are clear stylistic affinities in their energetic linework, and occasionally their works have been confused. Rowlandson, a leading figure in caricature and watercolour, likely influenced Howitt, and it's known Rowlandson sometimes commissioned Howitt to work on plates.

Howitt was also part of a circle that included George Morland (1763-1804), whose popular scenes of rural life and animals often shared similar subject matter, though treated with a different sensibility. He would have known other prominent sporting and animal artists like Philip Reinagle (1749-1833) and James Ward (1769-1859), whose careers overlapped significantly with his own. Ward, in particular, rose to become a major figure in animal painting, eventually becoming a Royal Academician.

His work can be situated alongside landscape and genre painters like Julius Caesar Ibbetson (1759-1817) and Francis Wheatley (1747-1801), who also depicted aspects of rural life, albeit often with a greater focus on human figures and picturesque scenery. The watercolour tradition was strong in this period, with artists like Paul Sandby (1731-1809) pioneering topographical landscape, providing a broader context for Howitt's own work in the medium. His collaborators included publishers like William Henry Wigstead, who also worked with Rowlandson. The slightly later Henry Alken (1785-1851) would continue the tradition of sporting prints, arguably influenced by Howitt's dynamic style.

Personal Life

Details about Howitt's personal life remain somewhat fragmented. His marriage to Elizabeth Rowlandson produced at least two children, a son, Samuel Howitt Jr., who also became an artist, and a daughter, Anna. As mentioned, contemporary accounts and later biographical notes suggest the marriage faced difficulties, possibly leading to separation. Some anecdotal sources, often linked to the circle around Rowlandson, hint at more complex personal entanglements, but these are harder to verify definitively.

What is clear is that Howitt maintained his connections within the art world, particularly through the Rowlandson family. His relationship with his cousin (or close friend, sources vary), the publisher Thomas Williamson, was also important, providing professional support and collaboration, particularly in the early stages of his career. Despite the financial pressures that initially drove him to professional art, Howitt seems to have navigated the commercial aspects of his career successfully, producing a large volume of work for various markets.

Later Years and Legacy

Samuel Howitt continued to work actively into the 1810s, producing illustrations, prints, and paintings. He resided for many years in Somers Town, a district of London popular with artists and writers at the time. He passed away there in 1822, aged around 66.

His legacy is substantial. He left behind a vast body of work that provides an invaluable visual record of British sport, wildlife, and aspects of colonial life in India during the Georgian era. His energetic style and keen observational skills made him one of the most distinctive sporting and animal artists of his generation. He successfully bridged the gap between the life of the country gentleman and the profession of the artist, bringing authenticity and dynamism to his chosen subjects.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent sporting illustrators, particularly in the medium of etching and aquatint. His works remain popular with collectors and are held in major public collections worldwide, including the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Library, the Natural History Museum in London, the Yale Center for British Art (which holds a significant collection of British sporting art, including works by Howitt), and numerous other institutions. Samuel Howitt endures as a vital and engaging chronicler of the natural world and the pursuits of country life in a period of significant social and cultural change.