Simkha Simkhovitch stands as a fascinating figure in twentieth-century art, a talent forged in the crucible of Imperial Russia, tempered by revolution, and later transplanted to the burgeoning art scene of the United States. His life (1893-1949) spanned periods of immense global upheaval and artistic innovation, and his work reflects a dedication to craft, a keen observational eye, and an ability to adapt his skills to diverse artistic demands, from intimate portraits to grand public murals. This exploration delves into the life, career, and legacy of an artist whose contributions, particularly within the American modernist movement and the Federal Art Project, deserve continued recognition.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in a Changing Russia

Born in 1893 near Kiev, Ukraine, then a vibrant part of the vast Russian Empire, Simkha Simkhovitch's early years coincided with a period of intense cultural and political ferment. The artistic landscape of Russia at the turn of the century was a dynamic interplay of traditional academicism, the burgeoning Russian avant-garde, and a growing interest in national folk traditions. It was in this environment that Simkhovitch's artistic inclinations began to take shape.

His formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg (then Petrograd). This institution, steeped in classical traditions, would have provided him with a rigorous foundation in drawing, painting, and composition. The Academy was a hub for aspiring artists from across the Empire, and its influence on Russian art was profound, even as new movements challenged its established norms. Figures like Ilya Repin, a master of Russian Realism, had long been associated with the Academy, setting a high bar for technical proficiency.

The cataclysmic events of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing Civil War dramatically reshaped the nation and its cultural institutions. For artists, this period was one of both unprecedented opportunity and profound uncertainty. Simkhovitch navigated these turbulent times, and his talent was recognized early in the new Soviet era. He achieved a significant milestone by winning first prize in the first Soviet art exhibition held after the Revolution. His award-winning painting, reportedly titled "Russian Revolution," was deemed significant enough to be hung in the State Revolutionary Museum, a testament to its perceived alignment with the spirit of the times or its artistic merit in capturing a pivotal historical moment.

During these early years in Russia and Ukraine, Simkhovitch's artistic output primarily focused on portraiture and still life. These genres, while traditional, offered avenues for exploring human character and the beauty of everyday objects, even amidst societal transformation. His skill in these areas would remain a constant throughout his career. He also participated in the Florence International Book Fair in 1922, suggesting an engagement with the broader European art and literary scene. By 1924, he was also creating illustrations for Soviet textbooks, a common way for artists to make a living and contribute to the new state's educational initiatives. However, the evolving political and artistic climate in the Soviet Union, which would increasingly favor Socialist Realism, may have contributed to his decision to seek opportunities elsewhere.

Emigration and a New Canvas: America

In 1924, Simkha Simkhovitch made the life-altering decision to immigrate to the United States. He joined a wave of artists, intellectuals, and others seeking refuge, freedom, or new opportunities in America. New York City, his new home, was rapidly becoming a global art center, a melting pot of international influences and homegrown talent. The American art scene of the 1920s was vibrant, with artists like Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe, Charles Demuth, and Man Ray pushing the boundaries of modernism.

Upon his arrival, Simkhovitch quickly began to establish himself. He held exhibitions at the Marie Sterner Gallery in New York, a notable venue that showcased both European and American modern artists. This provided him with crucial exposure and helped integrate him into the American art world. His European training and evident skill likely appealed to a gallery system interested in diverse talents.

He also developed a close association with the Whitney Museum of American Art. Founded by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the museum was dedicated to promoting contemporary American artists. This connection underscores Simkhovitch's growing recognition within American art circles. While a planned posthumous memorial exhibition at the Whitney was unfortunately cancelled due to disagreements between his widow and the curators, the initial intention speaks to the museum's regard for his work. His involvement with organizations like the American Artists Alliance further indicates his active participation in the artistic community.

The American Modernist: Portraits and Easel Paintings

In America, Simkhovitch continued to develop his artistic voice, embracing aspects of American Modernism while retaining his strong figurative grounding. His portraiture remained a significant part of his oeuvre. A notable example is his 1926 portrait of the silent film superstar Gloria Swanson. Created using a sophisticated mix of charcoal, pencil, colored pencil, and white chalk, this work captures the glamour and persona of a Hollywood icon during a transformative period in cinema. The choice of subject and the nuanced execution demonstrate Simkhovitch's ability to engage with contemporary American culture.

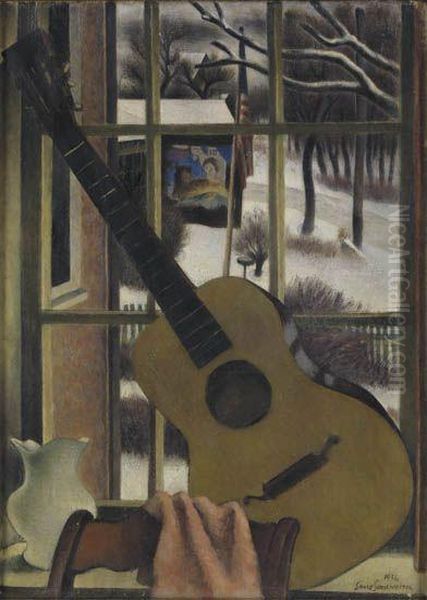

Beyond celebrity portraits, his easel paintings, including still lifes and other compositions, continued to showcase his technical skill and evolving style. One documented work, simply titled "Still Life," an oil on canvas measuring 57 x 46 cm, demonstrates his continued engagement with this genre. Such works allowed for explorations of form, color, and texture, hallmarks of modernist still life painting as practiced by artists like Stuart Davis or Preston Dickinson, though Simkhovitch's approach likely retained a more traditional, European sensibility.

His painting "Merry-Go-Round" suggests an interest in capturing scenes of American life and leisure, a theme popular among many artists of the era, including Reginald Marsh, who depicted the vibrant energy of urban entertainment. Simkhovitch's works from this period would have been exhibited alongside those of other American modernists, contributing to the diverse tapestry of art being produced in the country.

Murals and the Public Eye: The WPA Era

The Great Depression of the 1930s brought widespread economic hardship but also led to unprecedented government support for the arts in the United States. The Works Progress Administration (WPA), and specifically its Federal Art Project (FAP), employed thousands of artists, including Simkha Simkhovitch, to create art for public buildings. This initiative aimed to provide economic relief, beautify public spaces, and make art accessible to a wider audience. Mural painting became a prominent feature of the FAP, adorning post offices, schools, and government buildings across the country.

Simkhovitch became an active participant in these public art programs. He was commissioned to create significant mural projects, which stand as some of his most enduring legacies. One major commission was for the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse in Jackson, Mississippi. In 1938, he completed a mural titled "Pursuits of Life in Mississippi" for this building. Such murals often depicted scenes of local history, industry, agriculture, or daily life, aiming to resonate with the community. Simkhovitch's work in Jackson would have been part of this broader effort to create an "American Scene" in art, a movement also championed by Regionalist painters like Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, and John Steuart Curry, though WPA artists often had a more socially conscious or modernist bent.

Another significant WPA commission was for the U.S. Post Office in Beaufort, North Carolina. Here, Simkhovitch created a series of four oil-on-canvas murals, which were completed and installed in 1940. These works, including "Crissie Wright" and "Mail to Cape Lookout," depict scenes relevant to the coastal community of Beaufort, likely focusing on its maritime history, local legends, or daily activities. The fact that these murals are reported to remain in their original condition and location is a testament to their quality and the community's appreciation.

Working on these public murals, Simkhovitch would have been part of a cohort of artists dedicated to this democratic form of art. Figures like Ben Shahn, Philip Guston (in his earlier, more figurative phase), and Stefan Hirsch were also deeply involved in WPA mural projects. Indeed, Simkhovitch is noted to have been selected alongside Stefan Hirsch for mural commissions in Southern federal buildings, indicating a professional association and shared endeavor in this specific area of public art. The WPA murals provided artists with a steady income and a broad public platform, and Simkhovitch's contributions were clearly valued.

Artistic Circles, Contemporaries, and Influences

Throughout his career in America, Simkhovitch moved within various artistic circles. His exhibitions at galleries like Marie Sterner and his connection with the Whitney Museum placed him in the orbit of influential figures in the New York art world. His participation in the Federal Art Project naturally brought him into contact with a wide range of artists, administrators, and community members.

Beyond Stefan Hirsch, with whom he collaborated or was concurrently commissioned, and Valeri Shishkin, whose work appeared alongside his in an auction, Simkhovitch's contemporaries were numerous. The American art scene was rich with talent. In the realm of modernism, artists like Marsden Hartley, Arthur Dove, and John Marin were exploring new forms of expression. In figurative painting and social commentary, the Soyer brothers (Raphael, Moses, and Isaac) and Edward Hopper were making significant contributions.

While Simkhovitch's style was distinct, he would have been aware of these and other prevailing trends. The emphasis on American subjects, the exploration of modernist aesthetics, and the social consciousness spurred by the Depression all formed part of the artistic milieu in which he worked. His sister, Mary Kingsbury Simkhovitch, a prominent social reformer and founder of Greenwich House in New York, also connected him to a world of social activism and community engagement, which may have influenced his approach to public art. Greenwich House itself was a center for arts and crafts, further embedding the Simkhovitch family in New York's cultural and social fabric.

His work was included in significant exhibitions, such as the 1934 "A Century of Progress Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture" in Chicago, which showcased a wide array of contemporary art. This inclusion further demonstrates his standing among his peers. The artists he encountered, whether through exhibitions, professional organizations, or WPA projects, would have formed a network of influence and exchange, shaping the diverse landscape of American art in the first half of the 20th century. Other notable artists of the era whose paths he might have crossed or whose work he would have known include Charles Burchfield, known for his evocative watercolors of American scenes, and Yasuo Kuniyoshi, another immigrant artist who blended folk art influences with modernism.

Later Years, Legacy, and Posthumous Recognition

Simkha Simkhovitch continued to work as an artist throughout the 1940s. His dedication to his craft remained unwavering. However, his life was cut relatively short. In 1949, at the age of 55, he passed away from pneumonia in his new home in Milford, Connecticut. His death marked the loss of a skilled and versatile artist who had successfully bridged European traditions and American modernist currents.

The planned memorial exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which was unfortunately cancelled, highlights a poignant "what if" in his posthumous recognition. Such an exhibition at a major institution could have significantly solidified his reputation and brought his diverse body of work to a wider audience at a critical juncture.

Despite this setback, Simkhovitch's works have not been entirely forgotten. His murals in Jackson, Mississippi, and Beaufort, North Carolina, remain as public testaments to his skill and his contribution to the WPA's cultural legacy. These works are accessible to local communities and art historians, offering a direct engagement with his large-scale compositions.

His easel paintings and drawings also surface in collections and at auctions. For instance, a still life painting was noted to have been offered at auction in 2023 with an estimate of £400-£600. His portrait of Gloria Swanson has also appeared in the art market. The presence of his works in museum collections, including the Whitney, and in private hands ensures their preservation and potential for future study and exhibition.

The challenge for artists like Simkhovitch, who may not have achieved the superstar status of some of their contemporaries like Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning (who were part of the Abstract Expressionist wave that gained prominence around the time of Simkhovitch's death), is to ensure their contributions are not overlooked in broader art historical narratives. His journey from Tsarist Russia to the American art world, his technical proficiency, and his engagement with significant artistic and social movements of his time make him a compelling figure.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Simkha Simkhovitch's artistic journey was one of adaptation, resilience, and consistent dedication to his craft. From his academic training in St. Petersburg and early successes in post-revolutionary Russia to his establishment as a respected artist in the United States, he navigated profound historical changes and contributed meaningfully to the artistic landscapes he inhabited.

His portraits captured the likenesses of individuals from various walks of life, including celebrities like Gloria Swanson. His still lifes demonstrated a continued engagement with the formal qualities of painting. Perhaps most significantly, his WPA murals in Mississippi and North Carolina embody the democratic ideals of the Federal Art Project, bringing art into public spaces and reflecting local narratives. These murals, such as "Pursuits of Life in Mississippi," "Crissie Wright," and "Mail to Cape Lookout," stand as his most visible and enduring public works.

While the full measure of his recognition may have been impacted by his relatively early death and the cancellation of a key posthumous exhibition, Simkha Simkhovitch's oeuvre offers a rich field for appreciation and study. He was an artist who successfully integrated his European artistic heritage with the dynamism of American modernism, leaving behind a body of work that speaks to his skill, his versatility, and his engagement with the defining moments of the 20th century. His story is a valuable thread in the complex and diverse fabric of American art history.