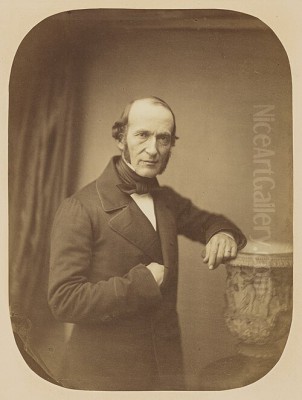

Simon Saint-Jean (1808-1860) stands as a pivotal figure in the rich tradition of French still-life painting, particularly renowned for his exquisite depictions of flowers and fruit. Born in Lyon, a city historically intertwined with the artistry of silk production and floral design, Saint-Jean rose to prominence during a period of significant artistic transition in France. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, vibrant realism, and a profound understanding of botanical forms, not only garnered him widespread acclaim during his lifetime but also left an indelible mark on the trajectory of still-life painting, especially within the celebrated Lyon School.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Lyon

Simon Saint-Jean's artistic journey began in Lyon, a city that, by the early 19th century, had already established a distinguished legacy in floral arts, partly fueled by its dominant silk industry which demanded intricate floral patterns. He was fortunate to receive his initial training under François Lepage, a respected flower painter. This foundational instruction was further honed at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts de Lyon (Lyon School of Fine Arts).

At the École, Saint-Jean excelled, notably in the flower painting class led by Augustin-Alexandre Thierriat. Thierriat himself was a significant painter and designer who succeeded the great Antoine Berjon as professor of the flower design class, a position crucial for training artists for the local silk industry. Saint-Jean's talent was recognized early when he won a gold medal in Thierriat's class. This academic success was a strong indicator of his burgeoning skill and dedication to the genre. Following his formal education, he briefly worked as a draughtsman for the textile firm Didier Petit et Cie, an experience that likely further refined his precision and understanding of floral composition for decorative purposes. However, his ambition lay in establishing himself as an independent easel painter. A significant early milestone was winning a gold medal in Paris in 1826, signaling his arrival on a broader artistic stage.

The Lyon School and its Floral Heritage

To fully appreciate Saint-Jean's contribution, it's essential to understand the context of the Lyon School of flower painting. Lyon had been a center for this genre since the 17th century, with artists like Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer and later, in the 18th century, Alexandre-François Desportes, though not Lyonnais themselves, setting high standards for French floral painting that resonated across the country. However, it was artists like Antoine Berjon (1754-1843) who truly revitalized and defined the Lyon School in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Berjon, with his precise yet lively style, elevated floral painting in Lyon, moving it beyond mere decoration.

Saint-Jean emerged as a leading figure in the generation following Berjon. While the silk industry's demand for floral designs provided a practical underpinning for many artists, Saint-Jean, like Berjon before him, sought to elevate flower painting to the status of high art. He focused on creating easel paintings intended for collectors and exhibitions, rather than solely patterns for textiles. This ambition was part of a broader movement where artists specializing in "minor" genres like still life were striving for greater recognition within the academic art world, which traditionally favored history painting.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Influences

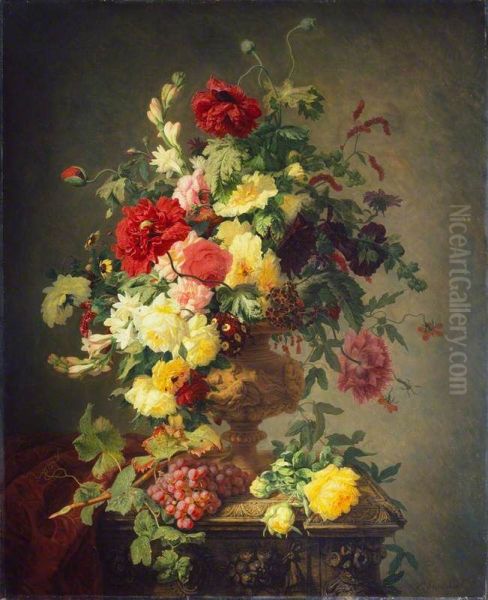

Simon Saint-Jean's style is characterized by an astonishing realism and meticulous attention to detail. He rendered flowers, fruits, and foliage with an almost scientific precision, capturing the delicate textures of petals, the subtle sheen on grapes, and the intricate venation of leaves. His technique involved smooth, often imperceptible brushstrokes, creating a highly polished finish that enhanced the illusion of reality. This precision was coupled with a sophisticated understanding of light and shadow, which he used to model forms and create a sense of depth and volume.

His compositions were typically abundant and lush, often featuring a rich variety of blooms artfully arranged in vases, baskets, or, more unusually, hats. He demonstrated a remarkable ability to balance complexity with harmony, ensuring that even his most opulent arrangements felt coherent and visually pleasing. His color palette was rich and vibrant, accurately reflecting the natural hues of the flora he depicted.

A significant influence on Saint-Jean, as with many still-life painters of his era, was the Dutch Golden Age masters of the 17th century. Artists like Jan van Huysum, Rachel Ruysch, and Jan Davidsz. de Heem had set unparalleled standards for botanical accuracy, complex compositions, and luminous detail. Saint-Jean absorbed these lessons, adapting their meticulous approach to the tastes and sensibilities of his own time. He often included a wide array of flowers such as roses, tulips, peonies, irises, and lilies, showcasing his virtuosity in rendering diverse botanical species.

Signature Works and Their Significance

Throughout his career, Simon Saint-Jean produced a remarkable body of work, with several paintings standing out as exemplars of his skill and artistic vision.

One of his early notable works is Corbeille de fleurs dans un chapeau (Flowers in a Hat), exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1833. This painting, innovative in its use of a fashionable hat as a container for an overflowing bouquet, showcased his technical brilliance and his ability to combine elegance with naturalism. The textures of the flowers, the straw hat, and the ribbons are rendered with exquisite care.

Offrande à la Vierge (Offering to the Virgin), also known as Fleurs devant une statue de la Vierge (Flowers before a Statue of the Virgin), painted in 1842 and now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, is another key work. This piece combines his mastery of floral depiction with a religious theme. A profusion of meticulously painted flowers, including roses (symbolic of the Virgin Mary), lilies, and tulips, are laid before a statue of the Madonna and Child. The painting demonstrates not only his technical prowess but also his ability to imbue his still lifes with symbolic and devotional meaning, a practice also seen in earlier Flemish and Dutch traditions.

La Jardinière (The Gardener's Daughter or Young Woman with Flowers), exhibited in 1837, is a larger and more ambitious composition that incorporates a figure alongside the floral arrangement. This work, also in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, depicts a young woman in a lush garden setting, holding a basket of freshly cut flowers. It blends portraiture with still life and landscape elements, showcasing Saint-Jean's versatility and his ability to create a narrative context for his floral subjects.

His later work, Nature morte aux raisins (Still Life with Grapes) from 1856, also housed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, highlights his continued mastery in depicting fruit. The translucency of the grapes, the velvety texture of peaches, and the interplay of light on the different surfaces are rendered with breathtaking realism. Such works solidified his reputation as a leading still-life painter of his generation.

Another piece, Emblèmes eucharistiques (Eucharistic Emblems) from 1841, further illustrates his engagement with religious symbolism, using flowers, grapes, and wheat to allude to the Eucharist. This demonstrates a depth beyond mere botanical representation, aligning his work with a long tradition of symbolic still life.

Recognition, Patronage, and Exhibitions

Simon Saint-Jean's talent did not go unnoticed. He was a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, the most important art exhibition in France, from 1831 onwards. He received numerous accolades throughout his career, including medals in 1831, 1834 (second class), 1840 (first class), 1841, and significantly, a first-class medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. This consistent recognition at the Salon was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success.

His works were highly sought after by collectors both in France and internationally. He attracted prestigious patrons, including members of the French aristocracy and even royalty. Notably, Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie were among his admirers and acquired his paintings. His fame extended beyond France; his works were exhibited at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and were also known in Russia. This international acclaim underscored the universal appeal of his meticulously crafted still lifes. The city of Lyon also recognized his importance, and the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon now holds a significant collection of his paintings, testament to his status as a local hero and a master of his genre.

Critical Reception: Praise and Controversy

While Simon Saint-Jean enjoyed considerable popular and official success, his work also attracted critical commentary, most famously from the influential poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire. In his Salon reviews of 1845 and 1846, Baudelaire offered a sharp critique of Saint-Jean's paintings. He dismissed them as "dining-room pictures" ("tableaux de salle à manger"), implying they were merely decorative and lacked deeper artistic or intellectual substance. Baudelaire found Saint-Jean's highly polished finish and meticulous detail to be overly laborious and perhaps lacking in painterly verve. He particularly criticized what he perceived as an excessive use of yellow in Saint-Jean's palette.

Baudelaire's critique, while harsh, reflected a growing shift in aesthetic sensibilities among some avant-garde circles, which were beginning to favor more expressive brushwork and a departure from strict academic realism, as seen in the works of artists like Eugène Delacroix, whom Baudelaire championed. However, Baudelaire's view was not universally shared. Many other critics and the public at large admired Saint-Jean's technical virtuosity and the sheer beauty of his paintings. Critics like Théophile Gautier, for instance, often praised artists who demonstrated high levels of finish and realism.

The anecdote recorded by his student, Jean-Pierre Lays (himself a notable Lyon painter), that "the master could paint a rose in two days," speaks volumes about Saint-Jean's painstaking approach and his dedication to achieving perfection in his floral depictions. This meticulousness was precisely what many patrons and Salon juries valued.

Saint-Jean's Place in 19th-Century Art

Simon Saint-Jean occupies an important position in the art of the 19th century, particularly within the realm of still life and the Lyon School. He is considered a key figure in the movement to elevate flower painting from a primarily decorative art, associated with industries like textile design, to a respected genre of fine art. His commitment to easel painting and his success at the Salon helped to legitimize still life as a serious artistic pursuit.

His work can be situated within the broader context of Realism, a dominant artistic movement in France from the 1840s. While Gustave Courbet, a leading figure of Realism, focused on scenes of rural life and social commentary, Saint-Jean applied Realist principles of objective observation and detailed representation to the world of flowers and fruit. His fidelity to nature was paramount.

Furthermore, Saint-Jean is seen as a pioneer in separating fine art from industrial design in Lyon. While his early training and the city's economy were linked to the silk industry, his career demonstrated a path for artists to achieve independent success through easel painting. He helped pave the way for what some have termed "paysagiste" or landscape-style flower painting, where floral arrangements were often depicted in more naturalistic, less formal settings, sometimes incorporating elements of landscape.

His dedication to his craft and the high quality of his output set a standard for other flower painters in Lyon and beyond. While his style remained rooted in a detailed, polished realism, his work contributed to the continued vitality of still-life painting throughout the 19th century, even as new movements like Impressionism, championed by artists such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (who also painted flowers, albeit in a very different style), began to emerge later in his career and after his death.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Simon Saint-Jean's influence was most directly felt within the Lyon School of painting. He inspired a generation of artists who continued Lyon's tradition of excellence in floral and still-life painting. Artists like Jean-Pierre Lays, Antoine Vollon (though Vollon's still lifes were often broader and more robust in handling), and later, Henri Fantin-Latour (who, while not strictly Lyonnais, became one of the most celebrated flower painters of the later 19th century, admired by Impressionists and traditionalists alike), all worked within or were aware of the strong tradition that Saint-Jean represented. Fantin-Latour, in particular, shared Saint-Jean's dedication to capturing the individual character of each flower, though his brushwork was often softer and more atmospheric.

The precision and beauty of Saint-Jean's work ensured its enduring appeal. His paintings continue to be admired for their technical mastery and their celebration of the natural world. He demonstrated that still life, in the hands of a skilled and sensitive artist, could be a vehicle for profound artistic expression. His efforts contributed to the genre's prestige, ensuring that the depiction of flowers and fruit remained a respected subject for artists.

His legacy is also preserved in the significant holdings of his work in public collections, most notably the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, which allows contemporary audiences to appreciate the depth and beauty of his art. He remains a testament to the rich artistic heritage of Lyon and a key figure in the history of French still-life painting.

Conclusion

Simon Saint-Jean was more than just a painter of pretty flowers; he was a master of his craft, a standard-bearer for the Lyon School, and an artist who, through dedication and exceptional talent, elevated the genre of still-life painting. His meticulous realism, vibrant colors, and sophisticated compositions captured the ephemeral beauty of the botanical world with unparalleled precision. Despite occasional criticism from avant-garde voices like Baudelaire, Saint-Jean achieved widespread acclaim, prestigious patronage, and lasting recognition for his contributions. His work serves as a vital link in the long chain of European still-life tradition, bridging the meticulousness of the Dutch Golden Age with the artistic currents of 19th-century France, and leaving a legacy of beauty that continues to captivate viewers today.