Introduction: A Man of Two Worlds

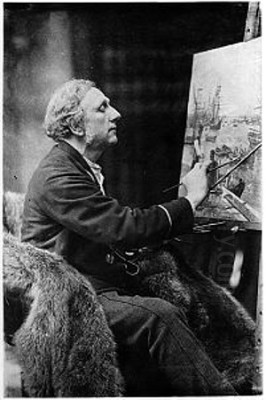

Sir Francis Seymour Haden stands as a remarkable figure in the annals of nineteenth-century British culture, a man who achieved eminence in two distinct and demanding fields: surgery and art. Born in London on September 16, 1818, and living a long and productive life until his death on June 1, 1910, Haden was not merely a competent practitioner in both medicine and printmaking; he excelled, leaving a lasting legacy in each domain. While his surgical career was distinguished, marked by innovation and compassion, it is perhaps his role as a master etcher and the principal driving force behind the British Etching Revival that secures his most enduring fame. He championed etching not as a reproductive craft, but as a vital, original medium for artistic expression, influencing generations of artists and reshaping the landscape of printmaking in Britain and beyond.

Haden's journey was shaped by a confluence of scientific discipline and artistic sensibility, likely nurtured by his family background – his father, Charles Thomas Haden, was a respected physician, and his mother, Emma Harrison, hailed from a family with musical inclinations. This dual inheritance equipped him with both the precision demanded by surgery and the aesthetic sensitivity that would blossom in his etchings. He navigated the seemingly disparate worlds of the operating theatre and the artist's studio with unique determination, proving that rigorous science and expressive art could coexist and even enrich one another within a single individual's life work. His story is one of passion, advocacy, technical mastery, and a profound impact on the art world of his time.

Early Life and Distinguished Medical Career

Francis Seymour Haden's formative years were spent in London, where he received his initial education. His path led him naturally towards medicine, following in his father's footsteps. He pursued his medical studies diligently at University College London and also gained practical experience at the Grenoble Hospital in France. His formal medical education culminated in Paris in 1840, where he successfully obtained his degrees in medicine and surgery, equipping him with the qualifications for a promising career. This period abroad, particularly his time in France and Italy around 1843-1844, was also crucial for nurturing his burgeoning interest in the visual arts, exposing him to masterpieces and likely planting the seeds for his later artistic pursuits.

Upon returning to London, Haden established a successful surgical practice. His skill and reputation grew steadily, leading to prestigious appointments and recognition. He served as Honorary Surgeon to the Department of Science and Art, a testament to his standing within the professional community. His medical expertise was sought even at the highest levels; he notably attended to Queen Victoria, indicating the trust placed in his abilities. Beyond serving the elite, Haden demonstrated a strong social conscience. He was instrumental in founding the Royal Hospital for Incurables (now the Royal Hospital for Neuro-disability), reflecting a commitment to providing care for those less fortunate and unable to afford medical treatment. His medical career was thus characterized by both professional excellence and humanitarian concern.

The Emergence of the Artist: Embracing Etching

Despite the demands of his flourishing medical practice, Haden's passion for art could not be suppressed. Largely self-taught as an artist, he was drawn specifically to the medium of etching. His initial foray into printmaking began around 1843-44 during his travels in Italy. He was captivated by the directness and expressive potential of the etched line, seeing it as a powerful tool for original artistic creation. This stood in stark contrast to the prevailing view of printmaking, particularly engraving, as primarily a means of reproducing paintings or other artworks. Haden became a fervent advocate for what he termed the "painter-etcher" – an artist who used the etching needle with the same creative freedom and intent as a painter used a brush.

Haden's artistic development was significantly influenced by his study of Old Masters, particularly the etchings of Rembrandt van Rijn. He deeply admired Rembrandt's mastery of light and shadow, his expressive line work, and his ability to convey profound emotion and atmosphere through etching and drypoint. Haden would later write extensively on Rembrandt's prints, contributing scholarly analysis to the understanding of the Dutch master's technique. He saw in Rembrandt the ultimate exemplar of the painter-etcher ideal he sought to revive. This deep engagement with the history of the medium provided a foundation for his own work and informed his passionate advocacy for etching's artistic legitimacy.

He articulated a clear distinction between the qualities of different printmaking techniques. For Haden, the freely drawn line of the etching needle, cutting through the wax ground on the copper plate, possessed an inherent "freedom, expression, and vivacity." He contrasted this favourably with the line produced by the burin in engraving, which he characterized as comparatively "cold, constrained, and uninteresting." This conviction about the superiority of etching for original expression became a cornerstone of his artistic philosophy and fueled his efforts to elevate the medium's status.

The Whistler Connection: Collaboration and Conflict

A pivotal relationship in Haden's artistic and personal life was his connection to the American-born artist James McNeill Whistler. This relationship was solidified in 1847 when Haden married Whistler's elder half-sister, Deborah (Dasha) Delano Whistler. The marriage brought the two men into close proximity, fostering a period of artistic exchange and collaboration, particularly during the 1850s. Whistler, younger and initially less established, spent considerable time in the Haden household in London, using Haden's printing press and benefiting from his brother-in-law's growing expertise and enthusiasm for etching.

Their shared interest led to direct collaboration. In 1858, they worked together on a series of etchings depicting the River Thames, a project that yielded some iconic images for both artists but also sowed the seeds of future discord. Whistler's famous "Thames Set" owes much to this period. Whistler even etched a portrait of Haden during these more amicable times, titled Seymour Standing Under a Tree, capturing his brother-in-law's imposing figure. Haden, in turn, provided encouragement and technical support to Whistler, contributing significantly to the younger artist's development as a printmaker.

However, the relationship between the two strong-willed, talented, and somewhat temperamental men eventually deteriorated dramatically. Artistic differences, financial disputes, and personal clashes led to a famous and acrimonious split. The final break reportedly occurred after a public argument in a Paris café in 1867, allegedly involving Whistler pushing Haden through a plate-glass window. This feud became legendary in the London art world, severing their personal and professional ties permanently. Despite the bitterness, their earlier interactions had been crucial in stimulating the burgeoning Etching Revival, with both men emerging as leading figures, albeit on divergent paths.

Championing the Etching Revival

By the mid-nineteenth century, original etching as practiced by masters like Rembrandt had largely fallen out of favour in Britain, overshadowed by reproductive engraving and the rise of newer technologies like lithography and photography. Haden emerged as the most articulate and influential champion for the medium's resurgence. He believed passionately that etching was not merely a craft but a high art form capable of profound originality and expression. He dedicated considerable energy to promoting this view through his writings, lectures, and organizational efforts.

Haden's advocacy was grounded in his deep understanding of the medium and its history. His studies of Rembrandt were central to this, allowing him to argue for the historical pedigree and artistic potential of etching. He published influential texts, including About Etching (1866) and The Etched Work of Rembrandt (1877), which helped to educate both artists and the public about the nuances and merits of the technique. He emphasized the autographic quality of etching – the direct trace of the artist's hand – and its suitability for spontaneous, expressive work, particularly landscape.

He actively contrasted the creative potential of etching and drypoint with what he saw as the laborious and less expressive nature of reproductive line engraving. He argued that the "painter-etcher" should work directly from nature, capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere with the immediacy that the etching needle allowed. This emphasis on originality and direct observation resonated with broader trends in nineteenth-century art, such as the Barbizon School in France and the Pre-Raphaelite focus on truth to nature, albeit interpreted through Haden's specific focus on line and tone in printmaking. His tireless promotion helped create a climate where artists felt encouraged to explore etching's possibilities and collectors began to appreciate original prints as valuable works of art in their own right.

Founding the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers

Haden's most significant institutional contribution to the Etching Revival was the founding of the Society of Painter-Etchers in 1880. Frustrated by the Royal Academy of Arts' perceived lack of recognition for original printmaking (often relegating prints to a separate, less prestigious category), Haden sought to create an organization dedicated specifically to promoting the art of etching and engraving as original forms of expression. He envisioned a society that would uphold high standards, provide a platform for exhibition, and advocate for the status of printmakers.

He served as the Society's first President, a role he held with distinction for three decades until his death in 1910. Under his leadership, the Society quickly gained prominence and influence. It attracted a diverse membership, including established and emerging artists from Britain and abroad. Haden was instrumental in persuading prominent international artists to join, such as the French realist Alphonse Legros (who had settled in London and taught at the Slade School of Art) and the society painter and etcher James Tissot. Other notable early members included Hubert von Herkomer and William Strang.

In 1888, the Society received a Royal Charter, becoming the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers (RE), a title it still holds today. This royal recognition was a major victory, cementing the status of original printmaking within the British art establishment. The Society's annual exhibitions became important events in the London art calendar, showcasing the best contemporary work in etching, drypoint, and engraving. Through the RE, Haden created a lasting institutional legacy that supported and promoted the art form he so passionately championed, ensuring its continued vitality long after his own time. The critic Philip Gilbert Hamerton, another important promoter of etching through his writings, recognized the significance of Haden's efforts in fostering this revival.

Artistic Style: Naturalism and the Expressive Line

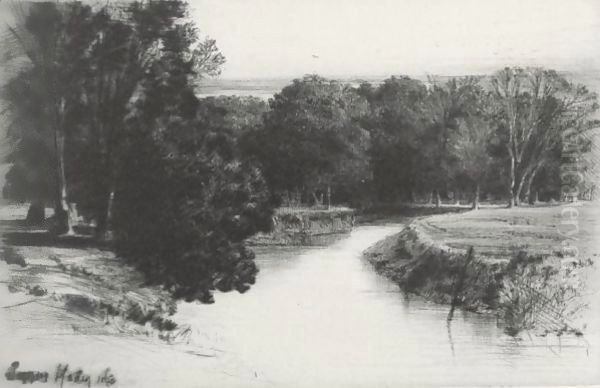

Haden's own artistic output consisted primarily of etchings and drypoints, focusing predominantly on landscape subjects. His style was rooted in naturalism, characterized by careful observation of the English countryside, riverscapes, and coastal scenes. He often worked directly on the plate outdoors, seeking to capture the specific atmosphere, light, and texture of a place with freshness and spontaneity. This practice aligned with his theoretical emphasis on direct engagement with nature.

Central to his aesthetic was the quality of the line itself. As previously noted, he championed the "free, expressive, vital" line achievable with the etching needle and drypoint tool. His works demonstrate a mastery of varied linework, from delicate, feathery strokes suggesting distant foliage or calm water, to bold, vigorous lines defining foreground elements or stormy skies. He was particularly adept at using drypoint, a technique where the artist scratches directly into the copper plate, raising a burr of metal that holds extra ink, producing rich, velvety lines. This technique added depth and tonal variety to his prints.

Haden also advocated for what he termed the "omission of labour" or "economy of line." This principle involved suggesting form and atmosphere through carefully placed lines and areas of untouched paper, rather than laboriously filling in every detail. He believed that leaving something to the viewer's imagination enhanced the artwork's power and vitality. This approach gives many of his prints an open, airy quality, emphasizing space and light. His compositions often feature strong diagonals, leading the eye into the landscape, and a sensitive balance between detailed passages and broader, more suggestive areas. His work, while distinct, shows an affinity with the tonal concerns of Barbizon painters like Charles-François Daubigny and the earlier landscape traditions of British artists like J.M.W. Turner, translated into the linear medium of etching.

Representative Works: Capturing the British Landscape

Over his long career, Haden produced over 250 plates. Several works stand out as particularly representative of his style and significant within his oeuvre.

Shere Mill Pond (No. 1) (1860): This early plate is one of Haden's most celebrated images. Depicting a tranquil scene in Surrey, it showcases his ability to render reflections in water and the textures of foliage with delicate precision. The composition, featuring a central pool flanked by trees and a rustic building, exemplifies his picturesque sensibility and mastery of atmospheric effect.

Hands Etching—Ö Laborum (1865): A departure from pure landscape, this etching shows Haden's own hands holding an etching needle and resting on a plate. It serves as a powerful statement about the dignity of the etcher's craft and the direct connection between the artist's hand and the resulting work. The title, referencing Horace's Odes ("Oh, the works..."), adds a layer of classical allusion to the theme of artistic labour.

The Towing Path (1864): This evocative river scene demonstrates Haden's skill in capturing the interplay of light, water, and sky. The composition leads the viewer along the riverbank, emphasizing the depth and tranquility of the landscape. The use of varied line weights effectively conveys different textures and distances.

Sunset in Ireland (1863): Created after a trip to County Tipperary, this dramatic drypoint is renowned for its rich, dark tones and expressive rendering of a sunset sky. The velvety blacks achieved through the drypoint burr create a powerful sense of mood and atmosphere, showcasing Haden's mastery of this technique.

Mytton Hall (1859): An early landscape showing the influence of his study of earlier masters, possibly including the work of Samuel Palmer whose own visionary landscapes were being rediscovered. It depicts an old manor house nestled in a lush, textured landscape.

Swanage Bay (1877): Mentioned as a representative work, this likely depicts the coastal scenery of Dorset, a region Haden visited. His coastal scenes often capture the dynamic relationship between land, sea, and sky.

Breaking up of the Agamemnon (1870, with later states): Considered one of his masterpieces, this large plate depicts the dismantling of a famous old battleship on the Thames. It is a powerful image of decay and the passage of time, rendered with dramatic contrasts of light and shadow and intricate detail. The subject matter, the end of a mighty vessel, carries symbolic weight, and Haden returned to the plate over several years, creating different states that highlight his evolving technique and interpretation. This work earned him considerable acclaim, including recognition at the Paris Exposition of 1889 where he won the Grand Prix for original etching.

These works, among many others, demonstrate Haden's consistent dedication to landscape, his technical virtuosity in etching and drypoint, and his ability to imbue his scenes with both topographical accuracy and profound mood. They secured his reputation as one of the foremost original etchers of his generation.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Sir Francis Seymour Haden's influence on the art world was substantial and multifaceted. His most significant contribution was undoubtedly his central role in reviving original etching in Britain. Through his own acclaimed work, his persuasive writings, his lectures, and his leadership of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers, he successfully elevated the status of etching from a primarily reproductive craft to a respected medium for original artistic expression. He inspired countless artists to take up the etching needle and explore its unique possibilities.

His impact extended beyond Britain. His advocacy resonated with similar etching revivals occurring in France, championed by figures like Charles Méryon (whose work Haden admired) and printers like Auguste Delâtre (who printed for both Haden and Whistler). The RE under Haden's presidency fostered international connections, creating a community that transcended national borders. Artists like Alphonse Legros, who became a highly influential teacher at the Slade School, helped to disseminate the principles of the Etching Revival to a new generation.

Subsequent generations of British printmakers, including prominent members of the RE like William Strang and Sir Frank Short (who succeeded Haden as President), built upon the foundations he laid. They continued to explore and expand the techniques of etching, drypoint, and mezzotint, ensuring the continued vitality of original printmaking into the twentieth century. Haden's emphasis on the expressive potential of line and the importance of the artist's direct involvement in the printing process remained influential principles.

His prints entered major public collections during his lifetime and continue to be sought after by museums and private collectors worldwide. His work is valued not only for its technical brilliance and aesthetic appeal but also as a key representation of the Victorian engagement with landscape and the successful campaign to legitimize printmaking as a fine art. While his name might not be as universally recognized today as that of his famous brother-in-law, Whistler, Haden's contribution to the history of printmaking remains undeniable and profound.

Other Interests: Burial Reform

Beyond his demanding careers in medicine and art, Haden engaged with other public issues, most notably the question of burial practices. In the later nineteenth century, debates raged about the hygiene and efficiency of traditional interment versus the newly revived practice of cremation. Haden became a vocal opponent of cremation and a strong advocate for a specific form of burial he termed "earth to earth."

In 1875, he published a series of letters to The Times, later collected in a book titled Earth to Earth: A Plea for a Change in Our System of Burial of the Dead. He argued that traditional Victorian burials, involving heavy, sealed coffins, hindered the natural process of decomposition, posing potential health risks and wasting valuable land. Instead, he proposed burial in perishable coffins (such as wicker or papier-mâché) placed directly in contact with the soil. He believed this would facilitate rapid, natural decomposition, returning the body to the elements efficiently and hygienically, allowing cemetery land to be reused more quickly.

His campaign for burial reform reflected his scientific background and his concern for public health and resource management. While cremation ultimately gained wider acceptance, Haden's arguments contributed significantly to the public discourse on death and burial practices during a period of significant social and sanitary reform. This interest reveals another dimension of his character – a practical, scientifically minded reformer engaging with the pressing social issues of his day.

Anecdotes and Personality

Anecdotes surrounding Haden often highlight his dual professions and his strong personality. The story of his leg injury during a trip illustrates the intersection of his medical knowledge and personal experience. Seeking treatment for a sprain, he was advised by a local doctor that simple bandaging would suffice. However, Haden's son later discovered the doctor had employed a rather unconventional and complex method involving covering the leg with glue. This incident perhaps reflects the varying standards of medical practice at the time and Haden's own likely critical perspective as an experienced surgeon.

His personality is often described as authoritative and sometimes combative, traits perhaps necessary for championing unpopular causes like the Etching Revival or burial reform. His famous feud with Whistler certainly points to a man capable of strong opinions and fierce disagreements. Yet, he was also clearly capable of inspiring loyalty and dedication, as evidenced by his long presidency of the RE and the respect he commanded in both medical and artistic circles. He was a man of immense energy, pursuing his passions with vigour and conviction throughout his long life.

Conclusion: A Victorian Polymath's Enduring Mark

Sir Francis Seymour Haden was a quintessential Victorian figure in his polymathic range of interests and achievements. He successfully bridged the worlds of science and art, achieving distinction as both a surgeon and a printmaker. His medical career was marked by skill, innovation, and compassion, while his artistic career fundamentally changed the course of British printmaking. As the driving force behind the Etching Revival, he rescued etching from the margins and re-established it as a vital medium for original artistic expression.

Through his own masterful etchings and drypoints, primarily focused on the landscapes he loved, he demonstrated the medium's capacity for subtlety, power, and directness. Through his writings and his founding of the Royal Society of Painter-Etchers and Engravers, he provided the intellectual framework and institutional support necessary for the revival to flourish. His influence extended to contemporaries like Whistler and Legros, and shaped the work of subsequent generations of printmakers such as Strang and Short. Even his engagement with practical matters like burial reform showcased his characteristic blend of scientific reasoning and passionate advocacy. Sir Francis Seymour Haden left an indelible mark, remembered as a skilled surgeon, a master etcher, and the indispensable catalyst who breathed new life into the art of printmaking.