Armand Seguin stands as a fascinating, albeit somewhat tragic, figure in the vibrant tapestry of late 19th-century French art. Born in 1869 and dying prematurely in 1903, his brief but intense career placed him at the heart of the Post-Impressionist movement, particularly within the influential circle of artists known as the Pont-Aven School. While his paintings are less numerous and often overshadowed by his contemporaries, Seguin's true genius and lasting contribution lie in his innovative and expressive work as a printmaker. His life, marked by artistic fervor, collaboration, poverty, and illness, offers a poignant glimpse into the struggles and triumphs of an artist dedicated to forging a new visual language.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Armand Seguin was born in Brittany, a region of France that would later become central to his artistic identity and output. Like many aspiring artists of his generation, he made his way to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world, to pursue formal training. He enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a private art school that offered an alternative to the rigid curriculum of the official École des Beaux-Arts. The Académie Julian was a crucible for many young talents who would go on to define modern art, including members of the Nabis group such as Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Maurice Denis.

Despite the academic environment, which still emphasized traditional techniques and classical subjects under figures like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert-Fleury, Seguin was drawn to the more radical artistic currents swirling through Paris. The late 1880s and early 1890s were a period of intense artistic experimentation, with Impressionism having already challenged academic conventions, and new movements like Symbolism and Synthetism beginning to emerge, championed by artists seeking deeper emotional and spiritual expression.

The Call of Pont-Aven and Synthetism

A pivotal moment in Seguin's artistic development came with his association with the Pont-Aven School. This loose collective of artists congregated in the remote Breton village of Pont-Aven and nearby Le Pouldu, drawn by the region's rugged beauty, distinct culture, and perceived authenticity, which offered an escape from the increasing industrialization and sophistication of Paris. The leading figures of this group were Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard, whose ideas profoundly shaped Seguin's artistic trajectory.

Seguin first visited Pont-Aven in 1891, where he encountered not only Gauguin and Bernard but also other notable artists like Auguste Renoir, who was briefly in the area. It was here that Seguin was exposed firsthand to the principles of Synthetism, an artistic style developed by Gauguin and Bernard. Synthetism advocated for a departure from the Impressionists' focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere. Instead, it emphasized simplified forms, strong outlines, flat areas of unmodulated color, and a subjective interpretation of reality, aiming to synthesize outward appearances with the artist's feelings and imagination. Paul Sérusier's seminal work, The Talisman, painted under Gauguin's direct instruction in 1888, became a key example of this new approach and a touchstone for artists like Seguin.

Mentorship and Collaboration

By 1893, Seguin had been formally introduced to Paul Gauguin and quickly came under his mentorship. Gauguin, a charismatic and forceful personality, encouraged Seguin to explore more expressive and less naturalistic forms. This guidance was crucial for Seguin, particularly in his printmaking endeavors. The same year, Seguin demonstrated his intellectual engagement with the new art by writing the preface for the catalogue of Gauguin's solo exhibition, a testament to his understanding of and commitment to Synthetist ideals.

Seguin also formed a close working relationship with Émile Bernard. Bernard, who had independently developed ideas similar to Gauguin's regarding simplified forms and spiritual content, was also an accomplished printmaker. It is believed that Seguin learned much about etching techniques from Bernard. Furthermore, Seguin collaborated with the Irish artist Roderic O'Conor, another key figure in the Pont-Aven circle, particularly in Le Pouldu. Together, they explored various etching techniques, pushing the boundaries of the medium. These interactions with Gauguin, Bernard, and O'Conor were instrumental in shaping Seguin's distinctive graphic style. Other artists active in the Pont-Aven milieu whose work shared some affinities included Charles Laval, Meyer de Haan, Charles Filiger, and Jan Verkade.

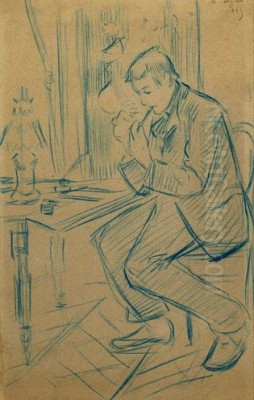

A Master of the Print

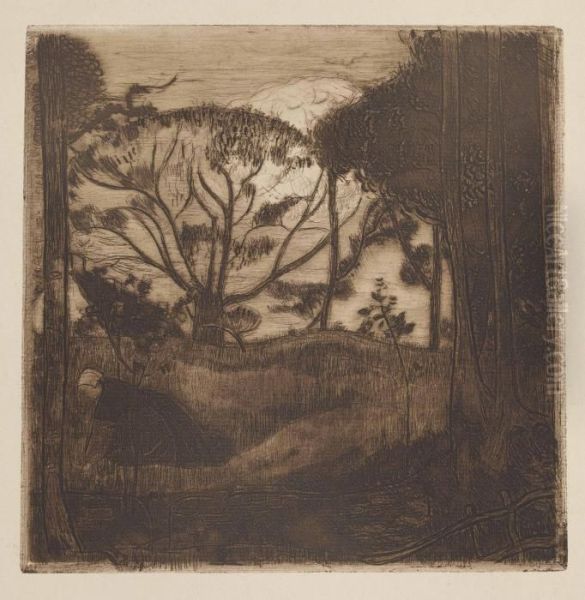

While Seguin considered himself primarily a painter, it is in the realm of printmaking that his most significant and enduring artistic achievements lie. He produced over ninety prints, primarily etchings, but also experimented with aquatint, drypoint, and often enhanced his prints with hand-applied watercolor, making each impression unique. His printmaking style is characterized by its emphasis on strong, sinuous lines, a flattening of perspective, and a decorative sensibility that aligns closely with the tenets of Synthetism and the burgeoning Art Nouveau movement.

Seguin's prints often depict scenes of Breton life, landscapes, and portraits, imbued with a sense of melancholy or introspection. He was particularly adept at capturing the rugged character of the Breton countryside and the stoic dignity of its inhabitants. His approach was not merely illustrative; rather, he sought to convey an emotional or symbolic essence. The influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, which had captivated many Post-Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Félix Vallotton, is evident in Seguin's work through his use of bold compositions, cropped perspectives, and decorative patterning.

His editions were typically very small, often ranging from only two to twenty-five impressions. This rarity, combined with their artistic quality, makes his prints highly sought after by collectors today. He often printed his own plates, allowing for a high degree of experimentation with inking and wiping techniques, further enhancing the individuality of each print.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Among Seguin's most celebrated prints are works that exemplify his mature style and thematic preoccupations. Le Soir (Evening, 1894) showcases his ability to evoke mood through simplified forms and atmospheric effects. La Grangeuse (The Barn Worker, 1894) and Les Rouisseuses (The Retters, 1894) depict Breton peasant women at work, rendered with a combination of starkness and decorative elegance. These works avoid sentimentalizing rural labor, instead focusing on the rhythmic patterns and essential forms of the figures within their environment.

La Jeune Fille de Pont-Aven (Young Girl of Pont-Aven, 1896) is a sensitive portrait that captures a sense of quiet contemplation. Another significant work, Nu de la Comtesse d'Hauteruche (Nude of the Countess d'Hauteruche, 1896), exists as both a painting and a print, demonstrating his exploration of the female form. This work, like many Symbolist pieces by artists such as Odilon Redon or even the earlier Gustave Moreau, hints at an inner world beyond mere physical representation.

Seguin's subjects often reflect the Pont-Aven School's interest in the "primitive" and the authentic, seeking inspiration away from the perceived artificiality of urban life. His figures, whether peasants or more enigmatic nudes, possess a certain gravity and are often integrated into decorative, almost abstract, backgrounds. The lines are fluid and expressive, defining form while also creating a rhythmic surface pattern.

The Painter's Path

Despite his prodigious talent as a printmaker, Armand Seguin consistently identified himself as a painter. However, his painted oeuvre is considerably smaller and less well-known than his graphic work. Financial constraints likely played a role, as painting materials were more expensive, and finding patrons for his often unconventional canvases proved difficult. His paintings, like his prints, show the influence of Synthetism, with simplified forms, bold colors, and an emphasis on emotional expression.

Works like the aforementioned Nude, Countess d'Hauteruche (1896) demonstrate his painterly concerns. He explored landscapes, portraits, and figure compositions, often imbued with the same Symbolist undertones found in his prints. However, the art market of the time, dominated by more established Impressionists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, or the rising stars of Neo-Impressionism like Georges Seurat, was not always receptive to the more idiosyncratic visions of artists like Seguin. The influential dealer Ambroise Vollard, who championed many avant-garde artists including Gauguin and Cézanne, did handle some of Seguin's prints, but widespread recognition for his paintings remained elusive during his lifetime.

A Life of Struggle and a Premature End

Armand Seguin's life was one of persistent financial hardship. Despite his talent and his connections within the avant-garde art world, he struggled to make a living from his art. This poverty was compounded by failing health. Like many artists of the period, including Amedeo Modigliani a couple of decades later, Seguin suffered from tuberculosis.

His dedication to his art remained unwavering despite these challenges. He continued to work in Brittany, particularly in Châteauneuf-du-Faou, where he spent his final years. The raw beauty and distinct cultural identity of Brittany continued to fuel his artistic imagination. However, his illness progressively weakened him, and Armand Seguin died in Châteauneuf-du-Faou in 1903, at the young age of 34. His early death cut short a career that, while already significant, held the promise of further development and innovation.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Seguin's artistic style is a compelling synthesis of several key late 19th-century artistic currents. At its core is Synthetism, learned directly from Gauguin and Bernard, evident in his use of simplified, expressive forms, strong outlines, and flattened color planes. This approach rejected the naturalistic detail and optical concerns of Impressionism in favor of conveying subjective experience and emotional truth.

The influence of Japanese woodblock prints is also undeniable, particularly in his prints. This can be seen in his asymmetrical compositions, the use of empty space, decorative patterning, and the emphasis on line. This Japonisme was a widespread phenomenon, impacting artists from Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt to the Nabis.

Symbolism also permeates Seguin's work. Rather than depicting the world as it appears, he often sought to evoke moods, ideas, or inner states. His figures can appear enigmatic, and his landscapes often possess a dreamlike or melancholic quality. This aligns with the broader Symbolist movement, which included painters, writers, and poets who prioritized imagination, emotion, and the spiritual over materialism and realism. Artists like Puvis de Chavannes, though stylistically different, shared this anti-naturalistic, evocative aim.

Finally, elements of Art Nouveau can be discerned in the flowing, organic lines and decorative qualities of his compositions, especially in his prints. The sinuous curves and emphasis on surface pattern connect his work to this international style that sought to integrate art into everyday life through design and ornament.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Armand Seguin's legacy is primarily secured by his remarkable body of prints. Though his paintings are less known, his graphic work stands as a significant contribution to the Post-Impressionist era and the revival of original printmaking as a major art form. His technical skill, combined with his unique artistic vision, resulted in prints that are both aesthetically compelling and emotionally resonant.

While perhaps not as widely recognized as his mentors Gauguin or Bernard, or other Pont-Aven associates like Sérusier, Seguin played an important role within this circle. He was an active participant in the development and dissemination of Synthetist ideas, both through his art and his writings. His prints, in particular, helped to popularize the aesthetic of the Pont-Aven School.

The rarity of his works, due to small edition sizes and his early death, has contributed to his somewhat niche status, but among connoisseurs of printmaking and Post-Impressionist art, he is highly regarded. Exhibitions and scholarly research continue to shed light on his contributions, ensuring that his unique voice is not lost to art history. His exploration of expressive line, simplified form, and subjective color prefigured aspects of later modern art movements, including Fauvism and Expressionism.

Conclusion: A Fleeting but Potent Vision

Armand Seguin's career, though tragically brief, was marked by intense creativity and a commitment to the avant-garde. As a key member of the Pont-Aven School, he absorbed and reinterpreted the radical ideas of Gauguin and Bernard, forging a distinctive style, particularly in the medium of printmaking. His etchings and other graphic works are celebrated for their technical mastery, decorative beauty, and evocative power, capturing the spirit of Brittany and the Symbolist undercurrents of his time.

Despite a life plagued by poverty and ill health, Seguin left behind a body of work that continues to fascinate and inspire. He remains a testament to the artistic ferment of the late 19th century, a period when artists boldly broke from tradition to explore new forms of expression. While the full arc of his potential was unrealized, Armand Seguin's contribution to Post-Impressionism, especially through his innovative and hauntingly beautiful prints, secures his place as a significant, if often underappreciated, artist of his generation. His work serves as a poignant reminder of a talent that burned brightly, albeit too briefly, in the rich artistic landscape of fin-de-siècle France.