Introduction: A Dominant Force in British Art

Sir Godfrey Kneller stands as one of the most significant figures in the history of British art, particularly during the late Stuart and early Georgian periods. Born Gottfried Kniller in Lübeck, Germany, on August 8, 1646, he would later anglicize his name and rise to become the preeminent portrait painter in England for nearly four decades. His arrival marked a pivotal moment, filling the void left by previous masters and establishing a style that would define the visual representation of the British elite until his death on October 19, 1723. Kneller's prolific output, his influential studio, and his unparalleled access to the highest echelons of society cemented his legacy as the face of British portraiture in the Baroque era.

Early Life and Continental Training

Godfrey Kneller hailed from an artistic background. His father, Zacharias Kneller, was a surveyor and portrait painter in Lübeck, providing an early exposure to the arts. Recognizing his son's talent, Zacharias ensured Godfrey received formal training. His artistic education began in the Netherlands, a powerhouse of painting in the 17th century. He studied under Ferdinand Bol, himself a notable pupil of the great Rembrandt van Rijn. While direct tutelage under Rembrandt is debated, Kneller was undoubtedly immersed in the artistic atmosphere of Amsterdam, absorbing the Dutch emphasis on realism, character study, and the dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) associated with Rembrandt and his circle.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Kneller, like many aspiring artists of his time, embarked on a journey to Italy in the early 1670s. He spent time in Rome and Venice, studying the works of the Italian masters and further refining his technique. In Italy, he would have encountered the grandeur of High Renaissance and Baroque art, absorbing lessons in composition, colour, and the depiction of classical themes and allegorical figures. This combination of Dutch realism and Italianate grandeur would become foundational elements of the distinctive style he later developed in England. His travels equipped him with a versatile skill set, ready to adapt to the demands of various patrons.

Arrival and Ascent in England

In 1676, Godfrey Kneller made the decisive move to England. London, recovering from the Great Fire and Plague but buzzing with Restoration-era energy, presented fertile ground for an ambitious portraitist. The demand for portraits among the aristocracy, the burgeoning merchant class, and the Royal Court was substantial. Kneller arrived at an opportune moment. Sir Peter Lely, the dominant court painter under Charles II, was still active but aging. Kneller quickly began to attract attention with his skillful likenesses and efficient working methods.

His breakthrough likely came through connections, possibly via the Duke of Monmouth. An early important commission involved painting King Charles II. Legend holds that Charles II was simultaneously sitting for Sir Peter Lely, and Kneller, working with remarkable speed and confidence, completed his portrait much faster, impressing the King. Whether apocryphal or not, the story highlights Kneller's efficiency, a trait that would become a hallmark of his career. He rapidly gained favour within court circles and among the wider aristocracy, establishing himself as a desirable alternative and soon-to-be successor to Lely.

Competition and Succession: The Mantle of Lely

The towering figure in English portraiture before Kneller's full ascendancy was Sir Peter Lely (born Pieter van der Faes). Lely, also of Dutch origin, had inherited the mantle from Sir Anthony van Dyck and had dominated the scene for decades, defining the languid, elegant style associated with the Restoration court. When Lely died in 1680, a significant vacuum appeared at the apex of the portrait market. Kneller was perfectly positioned to fill it.

While other talented portraitists were active, such as Willem Wissing (another Dutchman who enjoyed royal favour for a time) and John Riley (a skilled English painter), Kneller's combination of technical facility, speed, social adeptness, and ambition propelled him forward. He didn't simply imitate Lely; while his work certainly showed Lely's influence, particularly in the elegance of poses and richness of fabrics, Kneller often brought a slightly more direct, less overtly sensuous quality to his characterizations, especially in his male portraits. He rapidly eclipsed his rivals, securing the most prestigious commissions and consolidating his position.

Royal Appointments and Unprecedented Patronage

Kneller's success was cemented by consistent royal patronage that spanned an extraordinary five reigns. He initially painted for Charles II and continued under James II. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the new monarchs, William III and Mary II, appointed Kneller and John Riley as their joint Principal Painters to the Crown in 1689. This shared role acknowledged Riley's talent but also Kneller's undeniable prominence.

Upon John Riley's death in 1691, Kneller became the sole Principal Painter, a position he would retain through the reigns of Queen Anne and, subsequently, George I. This continuous service at the highest level was unprecedented and gave him unparalleled status and influence. He was responsible for creating the official images of the monarchs, shaping their public personae through numerous portraits distributed across the kingdom and abroad. His studio became the primary source for royal imagery, further solidifying his dominance in the field.

The Kneller Studio: A Portrait Factory?

To meet the immense demand for his work, Kneller established a large and highly organized studio in London's Covent Garden area. This operation functioned with remarkable efficiency, often compared to a factory. Kneller himself would typically focus on the most critical part of the portrait – the face and perhaps the hands – capturing the likeness and character of the sitter during sittings. The rest of the canvas, including the pose, costume, background elements (landscapes, columns, drapery), and sometimes even pets, would often be completed by a team of specialized assistants and pupils.

This studio system employed numerous artists, sometimes referred to as 'drapery men' or specialists in backgrounds. Names like Edward Byng and Marcellus Laroon the Younger are associated with his later studio practice. They worked from established patterns and poses, allowing for rapid production and the creation of multiple versions or copies of successful portraits. While this system enabled Kneller to produce an estimated output exceeding 5,000 works and made portraits accessible to a wider clientele, it inevitably led to variations in quality. Some works bearing his name show less of the master's hand, relying heavily on studio formulas. This practice, common in successful Baroque workshops like those of Rubens or Van Dyck, nonetheless drew criticism both during his lifetime and later for perceived commercialism and lack of consistent artistic engagement.

Signature Style and Techniques

Kneller's style synthesized his diverse training and adapted shrewdly to the tastes of his English clientele. It blended Dutch realism in capturing a likeness with the Baroque sense of grandeur and formality inherited from Van Dyck and Lely, albeit often with less flamboyance than his predecessors. His portraits project an air of confident authority and refined elegance, perfectly suited to the self-image of the British ruling class and intellectual elite.

Key characteristics of his style include:

Strong Likeness: Kneller was generally praised for his ability to capture a convincing resemblance of his sitters.

Elegant Poses: While often standardized, his poses conveyed status and composure. Men frequently stand with one hand tucked into a waistcoat or resting on a hip, while women are depicted with graceful gestures.

Rich Drapery and Textures: He and his studio excelled at rendering silks, velvets, and lace, adding to the sense of luxury.

Characteristic Wigs: His depiction of the large, fashionable wigs of the late 17th and early 18th centuries is iconic, often painted with fluid, confident brushstrokes.

Warm Palette: His colour palette often featured rich browns, reds, and golds, contributing to the overall warmth and dignity of the portraits.

Fluid Brushwork: In areas painted by Kneller himself, particularly faces, the brushwork can be lively and assured, suggesting form and texture efficiently.

Compared to continental contemporaries like the French masters Hyacinthe Rigaud or Nicolas de Largillière, Kneller's style was perhaps less overtly theatrical but possessed a solid, grounded quality that resonated with British sensibilities.

Major Works and Series: Documenting an Era

Beyond individual commissions, Kneller is renowned for several significant series of portraits that provide invaluable historical and social documentation.

The Hampton Court Beauties, commissioned around 1690-91 by Queen Mary II, depicts prominent ladies of the Royal Court. This series consciously echoed Lely's earlier Windsor Beauties from Charles II's reign. Housed at Hampton Court Palace, these portraits showcase Kneller's skill in rendering female elegance, fashionable attire, and idealized beauty, setting a standard for female portraiture of the period.

Perhaps his most famous collective work is the Kit-Cat Club series. Painted between roughly 1700 and 1720, this collection comprises over forty portraits of members of the influential Kit-Cat Club, a group primarily associated with Whig politics and culture. The club included leading writers, politicians, and thinkers like Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, Sir Robert Walpole, and the Duke of Marlborough. Commissioned largely by the publisher Jacob Tonson, the portraits were designed to hang in the club's meeting room. This necessitated a unique format, measuring 36 by 28 inches, which became known as the "Kit-cat" size. This canvas size, larger than a standard bust but smaller than a half-length, typically includes the sitter's head, shoulders, and one or both hands, allowing for more dynamic and informal poses than traditional bust portraits. The series captures a sense of intellectual camaraderie and political confidence, offering a remarkable group portrait of the men shaping early 18th-century Britain.

Notable Sitters: A Who's Who of the Age

Kneller's position as the leading court painter and society portraitist meant he painted virtually every significant figure in England over several decades. His sitters represent a cross-section of power, intellect, and fame in the late Stuart and early Georgian periods.

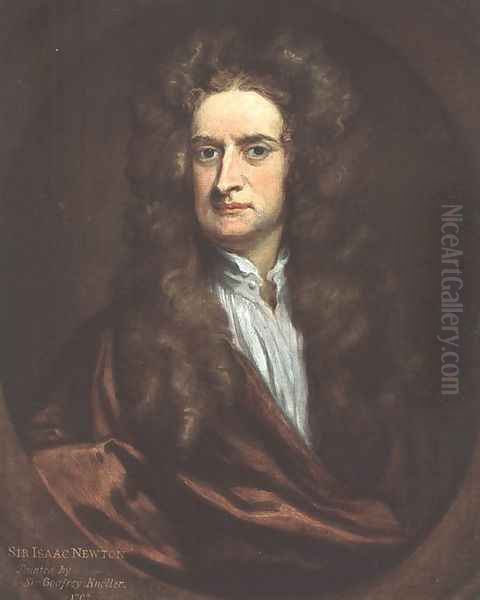

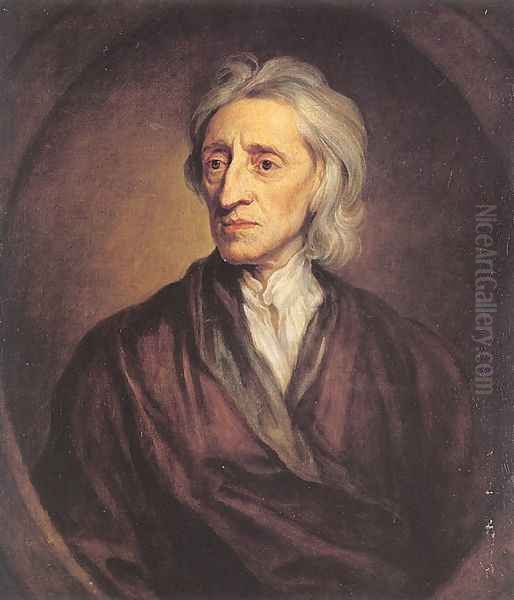

His royal portraits include multiple depictions of Charles II, James II, William III, Mary II, Queen Anne, and George I. Beyond the monarchy, he painted leading statesmen like Sidney Godolphin and Charles Montagu, 1st Earl of Halifax. Military heroes such as John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, sat for him multiple times. The intellectual giants of the age were also captured by his brush, most famously Sir Isaac Newton (several portraits exist) and the philosopher John Locke. He painted prominent writers and poets, including John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, Richard Steele, and William Congreve. Fellow artists and craftsmen, like the master carver Grinling Gibbons, were also among his subjects. This vast gallery of portraits serves as an unparalleled visual record of the era's key players. Note: While some sources mention John Milton, this is chronologically impossible as Milton died in 1674, before Kneller's arrival in England; Kneller did not paint him from life.

Character, Anecdotes, and Personal Life

Contemporary accounts and anecdotes paint a picture of Kneller as a man of considerable confidence, wit, and perhaps vanity, fully aware of his own status. One famous story, possibly embellished, involves a conversation with Alexander Pope. When Pope commented on the flattery often present in portraits, Kneller supposedly retorted, "Mr. Pope, you do not know me; if I had to paint God Almighty, I would give him a squint." While likely apocryphal in its exact wording, it reflects his reputation for sharp wit and perhaps a degree of irreverence.

His reported arrogance may have occasionally caused friction. An anecdote suggests his relationship with the devout James II cooled due to Kneller's perceived lack of deference or possibly his Protestant leanings. However, his ability to maintain favour across multiple, politically diverse reigns speaks volumes about his diplomatic skills and adaptability.

Kneller's personal life was somewhat unconventional for the time. He married a widow, Susanna Grave, but appears to have had a long-term relationship with a Mrs. Voss, who may have been his housekeeper or mistress, and with whom he had a daughter, Agnes. Later in life, he lived openly with Catherine Stuart. He acknowledged his illegitimate daughter Agnes, and much of his considerable fortune eventually passed to her illegitimate son, Godfrey Kneller Huckle, who became his heir. Kneller's famous remark about Westminster Abbey – reportedly saying he wouldn't be buried there because "they do bury fools there" – further illustrates his sharp tongue and self-assuredness.

Honours and Recognition

The scale of Kneller's success was formally recognized with significant honours bestowed by the Crown, elevating his social standing far above most artists of his time. In 1692, William III knighted him, making him Sir Godfrey Kneller. This was a mark of exceptional royal favour. His status was further elevated in 1715 when the newly arrived King George I made him a Baronet, a hereditary title. Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1st Baronet, thus achieved a level of social distinction rare for an artist in England. These honours reflected not only his artistic merit but also his central role in the cultural and political life of the nation, crafting the official image of its rulers and elite. He also served as Governor of the first artists' academy in London, founded in 1711 on Great Queen Street, demonstrating his leadership within the artistic community.

Influence and Legacy: Shaping British Portraiture

Sir Godfrey Kneller's influence on British portraiture was immense and long-lasting. For nearly half a century, his style was the dominant mode, setting the standard against which others were measured. His studio trained numerous assistants who disseminated his formulas and techniques. Artists like Jonathan Richardson the Elder, a notable portraitist and writer on art theory, operated within the stylistic parameters largely established by Kneller. Richardson's own pupil, Thomas Hudson, continued this tradition, directly linking Kneller's legacy to the next generation, which included Hudson's most famous pupil, Sir Joshua Reynolds.

While later artists like William Hogarth reacted against what they saw as the repetitive nature and foreign dominance of the Kneller school, even Hogarth's rebellion was framed by Kneller's pervasive influence. Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy, sought to elevate British art with his 'Grand Manner', but the very existence of a thriving, socially respected tradition of portraiture upon which Reynolds could build owed much to the status and prolific output Kneller had achieved. Kneller's work, particularly the Kit-cat format, also influenced portraiture in the American colonies.

Despite criticisms regarding the uneven quality resulting from his studio system and the perceived formulaic nature of some works, Kneller's best portraits display genuine psychological insight and technical brilliance. He effectively chronicled an entire era, leaving behind an invaluable visual record of British society at a time of significant political and cultural transformation. His success raised the status of artists in England and laid the groundwork for the flourishing of British painting in the later 18th century under artists like Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, and Allan Ramsay.

Conclusion: An Enduring Presence

Sir Godfrey Kneller dominated English portraiture from the 1680s until his death in 1723. His journey from Lübeck to the pinnacle of artistic success in London is a testament to his talent, ambition, and adaptability. Through his prolific output, efficient studio, and unparalleled royal and aristocratic patronage, he defined the visual identity of Baroque Britain. His portraits of kings, queens, politicians, scientists, writers, and beauties provide an indispensable window into the era. Though his methods sometimes invited criticism, his best works remain powerful examples of Baroque portraiture, capturing both likeness and status with confident mastery. Honoured with a knighthood and a baronetcy, he achieved remarkable social standing. True to his word, he was not buried among the "fools" of Westminster Abbey but at St Mary's Church, Twickenham, near the country house he had built. His legacy endures, not just in the thousands of portraits bearing his name, but in the foundational role he played in the development of a distinctly British school of painting.