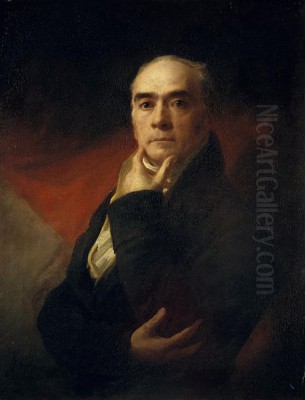

Sir Henry Raeburn stands as the preeminent Scottish portrait painter of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Active during a vibrant period of cultural and intellectual flourishing known as the Scottish Enlightenment, Raeburn captured the likenesses and characters of his nation's most prominent figures. Born in Stockbridge, then a village just outside Edinburgh, on March 4, 1756, he rose from humble beginnings to become a celebrated artist, knighted by the King and lauded as "The Reynolds of Scotland," a comparison to the leading English portraitist of the era, Sir Joshua Reynolds. His distinctive style, characterized by bold brushwork, dramatic lighting, and an uncanny ability to convey the sitter's personality, left an indelible mark on British art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Henry Raeburn's entry into the world was marked by early hardship. His father, Robert Raeburn, was a successful manufacturer in Edinburgh, but both he and Henry's mother, Ann Elder, passed away when Henry was young. The responsibility for his upbringing fell to his elder brother, William. Raeburn received his education at Heriot's Hospital, a charitable school in Edinburgh known for supporting orphaned children. While his formal education provided a foundation, his artistic inclinations soon began to surface.

In 1772, at the age of fifteen, Raeburn was apprenticed to the Edinburgh goldsmith James Gilliland. It was within this craft-based environment that his artistic talents first found an outlet. While learning the intricacies of metalwork and jewellery, he began experimenting with drawing and, notably, painting miniature portraits on ivory. These early works showed promise, demonstrating a natural aptitude for capturing likenesses, even on a small scale. His master, Gilliland, recognized his apprentice's talent and encouraged his artistic pursuits.

During his apprenticeship, Raeburn's burgeoning skills attracted the attention of other figures in Edinburgh's artistic community. He received guidance and likely some informal instruction from David Deuchar, an engraver and etcher. Perhaps more significantly, he came into contact with David Martin, who was, at that time, one of Edinburgh's leading portrait painters. Martin himself had trained under the celebrated Scottish portraitist Allan Ramsay, who had achieved fame in London and served as Principal Painter in Ordinary to King George III. Though largely self-taught, these early encounters and the opportunity to observe the work of established artists like Martin provided crucial exposure for the young Raeburn.

The Journey to Italy and the Influence of Masters

A pivotal moment in Raeburn's development came with his travels outside Scotland. While the provided text mentions a brief trip to Italy in 1775, biographical consensus places his significant Italian sojourn slightly later, likely around 1784-1785, after he had established himself somewhat and, crucially, after a formative encounter in London. He journeyed south to the bustling art capital, where he sought out the most famous British artist of the day, Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds, then President of the Royal Academy, recognized Raeburn's potential. He advised the younger painter to study the works of Michelangelo in Rome, though perhaps more practically, he provided letters of introduction to key figures within the Roman art scene.

Raeburn spent approximately two years in Italy, primarily in Rome. This period was essential for broadening his artistic horizons, although he did not simply copy the Italian masters. While he undoubtedly studied the works of Renaissance giants like Michelangelo, as Reynolds had suggested, he also absorbed the atmosphere and techniques of contemporary Roman artists. He connected with fellow Scotsman Gavin Hamilton, a neoclassical painter and archaeologist whose influence was significant among British artists visiting Rome. He also likely encountered the work of Pompeo Batoni, a leading Italian portraitist favoured by Grand Tour travellers.

Crucially, during his time in Rome, Raeburn received advice that profoundly shaped his working method. The collector and connoisseur James Byers urged him always to paint directly from life, never relying on memory even for secondary elements of a composition. Raeburn took this advice to heart, and it became a cornerstone of his practice. Unlike many contemporaries who relied heavily on preliminary drawings and sketches, Raeburn developed a technique of painting directly onto the canvas, building form and capturing likeness with immediate, decisive brushstrokes. This approach contributed significantly to the freshness and vitality characteristic of his work.

Edinburgh's Premier Portraitist

In 1787, Raeburn returned to his native Edinburgh, armed with newfound experience and a developing, distinctive style. He quickly established himself as the city's foremost portrait painter, effectively eclipsing his former mentor, David Martin. Edinburgh during this period was a hub of intellectual and cultural activity – the heart of the Scottish Enlightenment. Raeburn found himself perfectly positioned to chronicle the faces of this remarkable era.

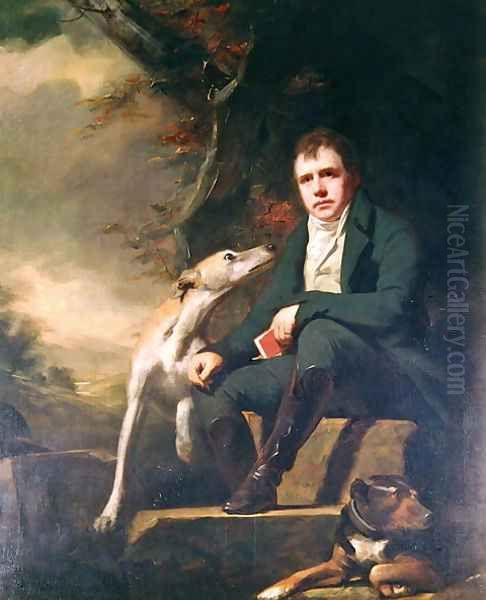

His studio became a magnet for the Scottish elite: lawyers, judges, physicians, academics, writers, landowners, and aristocrats. He painted leading figures of the Enlightenment, such as the philosopher David Hume and the economist Adam Smith, capturing not just their physical features but also conveying a sense of their intellectual weight and character. His sitters included influential members of society like Sir John Sinclair, whose portrait in full Highland dress is considered one of Raeburn's masterpieces, and Sir Walter Scott, the celebrated novelist and poet.

Raeburn's success was built on his ability to produce strong, convincing likenesses relatively quickly, thanks to his direct painting technique. His portraits were admired for their realism, their psychological insight, and their powerful presence. He developed a sophisticated understanding of how to pose his sitters and use lighting to enhance their features and express their personality. He often employed strong contrasts of light and shadow, sometimes using complex lighting setups in his studio to achieve dramatic effects, particularly focusing on the head and face as the primary locus of character. He produced a prodigious number of works, with estimates suggesting over 700 portraits completed during his career.

Artistic Style and Signature Techniques

Raeburn's style is instantly recognizable, marked by several key characteristics that set him apart from many of his British contemporaries. His approach was robust, direct, and deeply concerned with capturing the essential character of the sitter.

Direct Painting Method: As advised by Byers in Rome, Raeburn largely eschewed preparatory drawings. He preferred to work directly onto the canvas, applying paint with bold, square brushstrokes. This alla prima technique allowed him to capture a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. It required immense confidence and skill, as mistakes were harder to correct than in methods involving extensive underdrawing and layering. This directness contributes significantly to the feeling of encountering a living presence in his portraits.

Mastery of Light and Shadow (Chiaroscuro): Raeburn was a master of chiaroscuro, the use of strong contrasts between light and dark. He often employed dramatic lighting, sometimes placing the light source high and to one side, creating deep shadows that sculpt the form and add a sense of volume and three-dimensionality. Backlighting was also a favoured technique, silhouetting the sitter against a lighter background or creating a halo effect around the head. This manipulation of light was not merely technical; it served to heighten the psychological intensity and focus attention on the sitter's face.

Brushwork and Colour Palette: His brushwork was vigorous and expressive, often leaving visible strokes that contribute to the texture and energy of the painting. While sometimes described as 'rough' or 'square,' it was always controlled and purposeful, defining form with economy and precision. His colour palette tended towards rich, deep tones, often featuring strong reds, dark greens, and blacks, set against more muted backgrounds. He achieved harmony through careful tonal control, even when using bold colours.

Capturing Character and Likeness: While achieving a convincing physical likeness was paramount, Raeburn excelled at suggesting the sitter's inner life and personality. He had a particular talent for capturing fleeting expressions and conveying a sense of intelligence, authority, or sensitivity through subtle nuances in the eyes and mouth. His focus was often tightly cropped around the head and shoulders, minimizing distracting background elements to concentrate fully on the individual.

Romantic Sensibilities: Although working within the tradition of portraiture, Raeburn's work often displays elements associated with the burgeoning Romantic movement. This can be seen in the dramatic lighting, the psychological intensity, and occasionally in the choice of subject or setting. His portraits of Highland chieftains in traditional dress, like the aforementioned Sir John Sinclair, tap into the Romantic fascination with Scotland's history and landscape. There's often an air of rugged individualism and strength in his male portraits, and a sense of grace and composure in his female subjects.

Representative Works

Raeburn's extensive output includes many celebrated portraits that exemplify his unique style and skill. Among his most famous and representative works are:

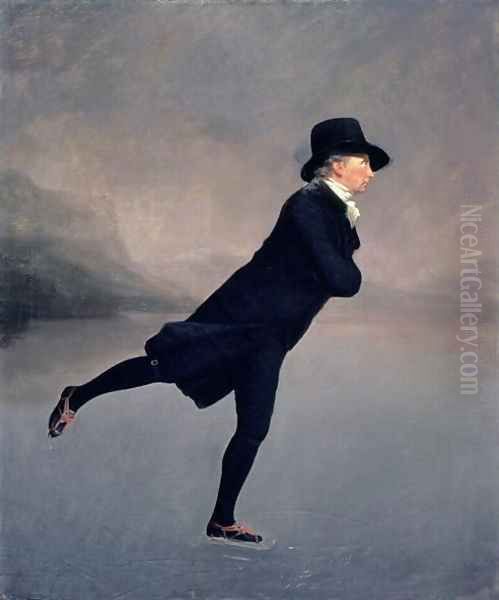

_The Reverend Robert Walker Skating on Duddingston Loch_ (c. 1795): Popularly known as The Skating Minister, this is arguably Raeburn's most iconic painting. Its unusual composition, depicting the clergyman gracefully gliding across the ice in a dynamic pose, was highly unconventional for portraiture of the time. The painting captures a sense of effortless movement and quiet concentration, rendered with fluid brushwork and subtle tonal gradations. It remains one of the most beloved images in Scottish art.

_Sir John Sinclair_ (1794-1795): This imposing full-length portrait showcases Raeburn's ability to handle formal commissions with grandeur and flair. Sinclair, an agricultural reformer and politician, is depicted in full Highland attire, complete with kilt and plaid, standing confidently in a landscape setting. The painting is notable for its rich detail, strong characterization, and masterful handling of textures, from the wool of the tartan to the sitter's determined expression.

_Boy and Rabbit_ (1814): This charming portrait demonstrates Raeburn's sensitivity in depicting children. The young boy, often identified as Henry Raeburn Inglis, the artist's step-grandson, gently holds a white rabbit. The work is admired for its tender atmosphere, soft lighting, and the natural, unposed quality of the subject. It showcases a gentler side of Raeburn's artistry compared to his more formal male portraits.

_Mrs John Campbell of Kilberry_: This portrait is often cited as an example of Raeburn's elegant and insightful portrayal of female sitters. His ability to capture both beauty and intelligence, using subtle modelling and expressive brushwork, is evident in such works.

_William Fraser of Reelig_ (c. 1801): Considered another masterpiece, this portrait exemplifies Raeburn's mature style, characterized by strong lighting, confident brushwork, and a powerful sense of the sitter's presence and personality.

Portraits of Enlightenment Figures: His depictions of individuals like Alexander Carlyle and John Home are valuable not only as artistic achievements but also as historical documents, providing insight into the faces and personalities that shaped a pivotal era in Scottish history. His portraits of Adam Smith and David Hume similarly capture the intellectual gravity of these influential thinkers.

_Portrait of Mrs. Sotheby or the Isted Families_ (c. 1795): This work is noted for its sophisticated handling of light and shadow, demonstrating Raeburn's technical prowess in modelling form and creating atmosphere.

_John Scott, Laird of Gala_: Mentioned as potentially his last work, this portrait would represent the culmination of his skills, likely displaying the directness, strong characterization, and mastery of technique honed over a long career.

These works, among many others, solidified Raeburn's reputation and continue to be admired for their artistic merit and historical significance.

Professional Recognition and Later Life

Raeburn's success in Edinburgh eventually translated into recognition on a wider British stage. Although he remained based in Scotland for almost his entire career, resisting the pull of London that drew many other artists, he sought and achieved membership in the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London. He was elected an Associate (ARA) in 1812 and became a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1815. He also played a leading role in the artistic life of his home city, serving as President of the Society of Artists in Edinburgh in 1812.

His reputation reached its zenith in 1822 during the historic visit of King George IV to Scotland, the first visit by a reigning monarch in nearly two centuries. During this celebrated event, Raeburn was knighted by the King at Hopetoun House. Shortly thereafter, he was appointed as His Majesty's Limner and Painter for Scotland, a prestigious royal post, although he sadly did not live long to enjoy the title.

Despite his artistic focus, Raeburn was known for his well-rounded personality. He was reportedly an engaging and humorous conversationalist, popular in Edinburgh society. He was also a keen sportsman, enjoying activities like golf and archery, pursuits that perhaps contributed to the sense of vitality found in his work. While he faced some financial difficulties later in life, possibly due to investments unrelated to his art, his professional standing remained high. He maintained connections with leading figures not just in Scotland but also corresponded with prominent London artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence, who succeeded Reynolds as the dominant force in English portraiture. While their styles differed – Lawrence's being perhaps more polished and flamboyant – they were the leading portraitists of their respective nations during the early 19th century.

Sir Henry Raeburn died in Edinburgh on July 8, 1823, less than a year after receiving his knighthood. He was buried in St John's Episcopal Churchyard at the west end of Princes Street, Edinburgh.

Legacy and Influence

Sir Henry Raeburn's legacy is firmly secured as Scotland's greatest portrait painter. He defined the image of the Scottish Enlightenment, capturing its key figures with unparalleled skill and psychological depth. His direct, vigorous style, characterized by bold brushwork and dramatic lighting, offered a distinct alternative to the smoother, more idealized approach often favoured by his English contemporaries like Reynolds or Thomas Gainsborough, or the refined elegance of George Romney.

While he did not run a large studio or formally train many pupils in the manner of Reynolds, his work undoubtedly influenced subsequent generations of Scottish artists, such as Sir John Watson Gordon, who followed him as the leading portraitist in Edinburgh. Raeburn demonstrated that an artist could achieve national and international recognition while remaining firmly rooted in Scotland.

Today, his paintings are prized possessions in major collections around the world. The National Galleries of Scotland holds the most extensive collection of his work, offering a comprehensive overview of his career. His portraits can also be found in prominent institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in California, the National Portrait Gallery in London, and Tate Britain, among others. His enduring appeal lies in the powerful sense of presence he conveyed, allowing viewers centuries later to feel a direct connection with the individuals who shaped Scotland during a remarkable period of its history.

Conclusion

Sir Henry Raeburn was more than just a recorder of faces; he was a master interpreter of character, working during a golden age of Scottish culture. From his beginnings as a goldsmith's apprentice, he developed a unique and powerful style of portraiture through self-directed study and a keen observation of life. His bold technique, dramatic use of light, and insightful characterizations made him the undisputed master of portrait painting in Scotland. His legacy endures not only in the numerous portraits that grace gallery walls but also in the vivid image he created of the Scottish Enlightenment and its people, securing his place as a pivotal figure in British art history.