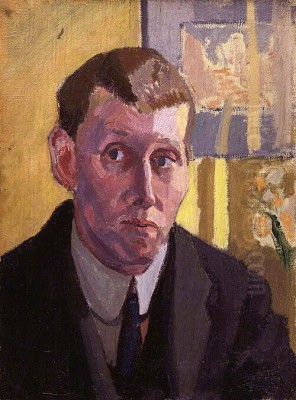

Spencer Frederick Gore stands as a significant yet tragically short-lived figure in the narrative of early 20th-century British art. A painter celebrated for his vibrant landscapes, intimate interiors, and atmospheric music hall scenes, Gore was instrumental in introducing and adapting Post-Impressionist ideas to a British context. As a founding member and the first president of the influential Camden Town Group, his work and organizational efforts played a crucial role in steering British painting away from Victorian constraints towards a modern sensibility. His life, though brief (1878-1914), was marked by intense artistic exploration and collaboration.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Spencer Frederick Gore was born on 26 May 1878 in Epsom, Surrey. His background was privileged; his father, also named Spencer Gore, was a celebrated sportsman, notably the first winner of the Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Championships. His mother was Amy Margaret Smith. This comfortable upbringing allowed him access to a good education, first at Harrow School, a prestigious institution known for nurturing talent across various fields. It was during his time at Harrow that Gore's artistic inclinations began to solidify.

Following Harrow, Gore enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in London in 1896, studying there until 1899. The Slade, under the directorship of figures like Frederick Brown and Henry Tonks, was becoming a powerhouse of artistic training in Britain, known for its emphasis on draughtsmanship and a relatively liberal approach compared to the Royal Academy Schools. Here, Gore was part of a remarkable generation of artists, studying alongside future luminaries such as Augustus John, William Orpen, and Albert Rutherston. This environment fostered experimentation and exposed him to diverse artistic currents, laying the groundwork for his future development.

Developing Style: Influences and Early Work

Gore's early work showed competence within established traditions, but a pivotal moment occurred around 1904. Through his growing friendship with the slightly older and more established artist Walter Sickert, whom he likely met around this time, Gore was introduced more profoundly to the developments in French art. Sickert, who had connections with Edgar Degas and had spent considerable time in France, particularly in Dieppe, became a crucial mentor figure. Gore visited Sickert in Dieppe, immersing himself in an atmosphere receptive to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

This exposure ignited Gore's interest in light, colour, and modern subject matter. He began to move away from purely academic approaches, embracing the brighter palettes and broken brushwork associated with Impressionism. Furthermore, he started to engage deeply with the structural concerns of Paul Cézanne and the expressive colour and flattened forms of Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh. These Post-Impressionist masters became guiding stars for Gore and his contemporaries as they sought a new language for British art.

His subject matter also began to reflect modern life. While landscapes remained central, he was drawn to urban scenes and places of popular entertainment. Early examples include his depictions of London music halls, such as The Alhambra (c. 1906), capturing the artificial light and bustling atmosphere, a theme he shared with Sickert and Degas.

The Fitzroy Street Group

By 1907, Gore was deeply embedded within a circle of progressive artists gravitating around Walter Sickert. This led to the formation of the Fitzroy Street Group. Based at Sickert's studio at 19 Fitzroy Street, and later expanding to number 8, the group served as an informal collective. Its primary aim was practical: to provide a space where members could show and potentially sell their work directly to patrons during weekly Saturday afternoon "at homes," bypassing the more conservative selection committees of established institutions like the Royal Academy.

Gore was a central figure in this venture alongside Sickert, Harold Gilman, Robert Bevan, and later Charles Ginner and Lucien Pissarro (son of the Impressionist Camille Pissarro). The Fitzroy Street Group fostered a sense of community and shared purpose among artists exploring similar Post-Impressionist avenues. It became a hub for discussion and mutual support, laying the organizational and aesthetic groundwork for the more formal group that would follow.

The Allied Artists' Association

Parallel to the Fitzroy Street activities, Gore was involved in another initiative aimed at creating alternative exhibition venues. In 1908, he helped the critic Frank Rutter establish the Allied Artists' Association (AAA). Modelled on the French Salon des Indépendants, the AAA operated on a no-jury, subscription-based system. Any member who paid the fee could exhibit a certain number of works.

This democratic approach provided a vital platform for avant-garde artists who struggled to gain acceptance elsewhere. Gore exhibited at the AAA's large annual exhibitions held at the Royal Albert Hall. These shows were instrumental in bringing modern art, including international works (Wassily Kandinsky exhibited there in 1909), to a wider London audience and further cemented Gore's position within the progressive art scene.

The Camden Town Group: Foundation and Vision

The culmination of these collaborative efforts was the formation of the Camden Town Group in 1911. Emerging directly from the core membership of the Fitzroy Street Group, the Camden Town Group was a more exclusive, male-only exhibiting society. Spencer Gore was elected its first president, a testament to his respected position among his peers. The group's name derived from the area of North London where Sickert, Gore, and others lived and worked, finding inspiration in its gritty urban landscapes and domestic interiors.

The group held only three exhibitions (in 1911 and 1912) but had a significant impact. Its members, including Gore, Sickert, Gilman, Bevan, Ginner, Lucien Pissarro, Walter Bayes, J.B. Manson, William Ratcliffe, Malcolm Drummond, and briefly Wyndham Lewis and Duncan Grant, shared a commitment to depicting contemporary British life using techniques derived from French Post-Impressionism. They focused on subjects like modest interiors, townscapes, portraits, and scenes of everyday life, often rendered with bold colour, simplified forms, and a focus on design and structure.

Gore's leadership was crucial during this formative period. He helped shape the group's identity and provided a steadying influence amidst the diverse personalities and sometimes diverging artistic aims of its members.

Gore's Subject Matter and Technique

Throughout his mature period, Gore's art was characterized by a vibrant engagement with colour and a keen observation of his surroundings. His technique evolved under the influence of Post-Impressionism. He often employed broken brushwork, applying paint in distinct touches that allowed underlying layers or the canvas itself to contribute to the overall effect. His palette became increasingly bold and sometimes non-naturalistic, using colour to convey emotion and structure rather than simply describing appearances.

The influence of Lucien Pissarro introduced Gore to Neo-Impressionist or Divisionist ideas, leading to experiments with a more systematic application of colour dots or small strokes, although Gore adapted these techniques freely rather than adhering strictly to theory. The structural solidity he admired in Cézanne is evident in the way he composed his landscapes and interiors, seeking underlying geometric forms.

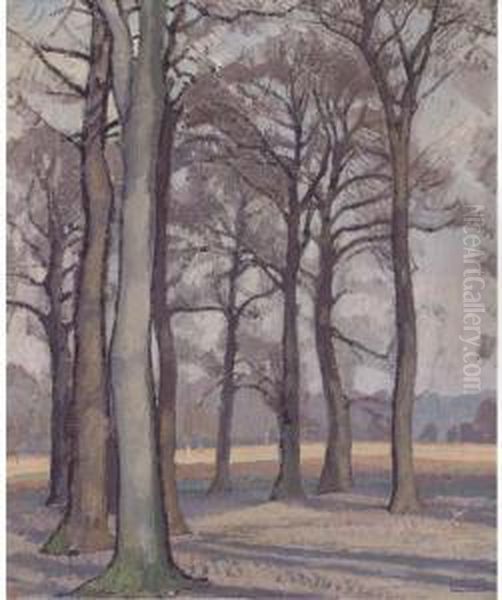

Landscapes formed a major part of his output. He painted frequently in Hertfordshire and later in Letchworth Garden City and Richmond. Works like The Beanfield, Letchworth (1912) and The Cinder Path (1912) exemplify his ability to find beauty and pictorial interest in seemingly mundane rural or semi-industrial settings, using strong colours and simplified shapes to create powerful compositions.

Urban scenes, particularly those around Mornington Crescent in Camden Town where he lived for a time, also feature prominently. These often depict views from windows, capturing the patterns of streets, squares, and railway lines. His interior scenes, sometimes featuring his wife Mollie Kerr, whom he married in 1912, are intimate studies of domestic life, notable for their handling of light and pattern.

The Letchworth Period

In 1912, Gore spent a significant period living and working in Letchworth Garden City, Hertfordshire. This planned town, founded on utopian ideals, provided a unique environment that blended rural landscapes with modern development. Gore, often accompanied by Harold Gilman, produced some of his most celebrated works during this time.

His Letchworth paintings, such as Letchworth Station (1912) and the aforementioned The Beanfield and The Cinder Path, are marked by particularly high-keyed colour and bold, simplified designs. They capture the specific character of the Garden City landscape – its fields, pathways, railway lines, and distinctive architecture – with a freshness and intensity that reflects the peak of his engagement with Post-Impressionist colour theory, likely influenced by his close association with Gilman and Lucien Pissarro. This period represents a high point in his exploration of landscape painting.

Music Halls and Theatrical Scenes

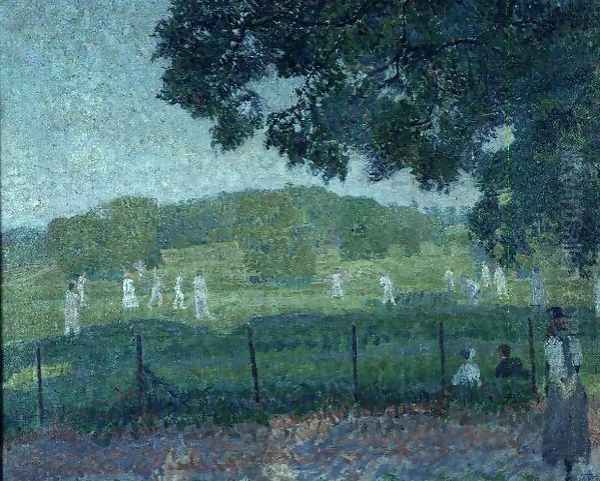

Alongside landscapes and interiors, Gore maintained an interest in scenes of entertainment, particularly the music hall and ballet. These subjects, popularised by Degas and Sickert, offered opportunities to explore artificial light, dynamic compositions, and the spectacle of modern urban leisure.

Works like Rule Britannia (c. 1910), depicting a performance at the Alhambra Theatre, showcase his ability to capture the energy and atmosphere of the stage. He used strong colours and bold shapes to convey the theatricality of the scene, focusing on the performers and the interplay of light and shadow. These paintings connect him to a lineage of artists fascinated by the world of performance, while also demonstrating his distinctive Post-Impressionist style.

The Richmond Period and Later Work

In late 1913, seeking cleaner air for his young family, Gore moved from London to Richmond-upon-Thames. He rented a house at 6 Cambrian Road, and the view from its windows became the subject of a remarkable series of paintings. Works like From a Window in Cambrian Road, Richmond (1913) show his continuing fascination with urban landscape, capturing the suburban street scene with vibrant colour and simplified forms.

His final major works were a series of landscapes painted in Richmond Park during the exceptionally cold early months of 1914. These paintings, such as Richmond Park (c. 1914), are characterized by stark compositions and sometimes unusual colour combinations, possibly hinting at an emerging interest in Fauvist or even Expressionist tendencies. The flattened perspectives and bold patterning suggest a move towards greater abstraction.

It was while painting outdoors in Richmond Park during this harsh weather that Gore contracted pneumonia. His dedication to capturing the winter landscape directly, despite the conditions, ultimately led to his premature death.

The London Group

The Camden Town Group, despite its impact, was short-lived as a formal entity. By late 1913, discussions were underway to merge it with other small exhibiting societies, including members of the Fitzroy Street circle who hadn't joined the Camden Town Group and elements from other avant-garde factions like Wyndham Lewis's Vorticist-inclined artists. This amalgamation resulted in the formation of the London Group.

Gore was a founding member of the London Group, which held its first exhibition in 1914. This new, larger organization aimed to provide a broader platform for modern art in Britain, encompassing a wider range of styles than the more focused Camden Town Group. Gore's involvement underscores his continued commitment to collective action and the promotion of progressive art, even as his own style continued to evolve.

Relationships and Collaborations

Gore's artistic life was deeply intertwined with his friendships and collaborations. His relationship with Walter Sickert was foundational, providing mentorship, inspiration, and a crucial link to French modernism. Though their approaches sometimes diverged, their mutual respect remained.

His bond with Harold Gilman was particularly close, especially during the Letchworth period. They shared studios, painted side-by-side, and clearly influenced each other's use of intense colour and bold handling. The slightly differing temperaments – Gore perhaps more lyrical, Gilman more starkly realistic – created a dynamic interplay.

His friendship with Lucien Pissarro provided a direct connection to Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist theory and practice. Discussions with Pissarro undoubtedly informed Gore's experiments with colour division. He also maintained close working relationships with Robert Bevan and Charles Ginner, core members of the Fitzroy Street and Camden Town circles, sharing subjects and exhibiting together frequently. His sociability and respected position made him a unifying force within these groups.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

Spencer Gore's significance in British art history rests on several key contributions. He was a crucial conduit for Post-Impressionist ideas, adapting the lessons of Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and the Neo-Impressionists into a distinctly British idiom. His work demonstrated that modern French techniques could be applied to English subjects – landscapes, cityscapes, and domestic scenes.

As the first president of the Camden Town Group, he played a vital organizational role in establishing one of the most important movements in early 20th-century British art. The group provided a focus and platform for artists seeking to break from academic tradition and engage with contemporary life and modern aesthetics. Critics like Frank Rutter and Roger Fry (who curated the seminal Post-Impressionist exhibitions in London in 1910 and 1912, which Gore saw and absorbed) recognized the importance of Gore and his circle in revitalizing British painting.

His premature death in March 1914, at the age of just 35, was a profound loss. He was at the height of his powers, his art still evolving, and his leadership within the London Group just beginning. It is impossible to know how his style might have developed had he lived through the war years and beyond. Nevertheless, his existing body of work secured his reputation. He influenced subsequent generations of British painters who continued to explore colour, form, and the depiction of everyday life. Artists associated with the Euston Road School in the 1930s, for instance, looked back to the Camden Town painters, including Gore, for inspiration.

Conclusion

Spencer Frederick Gore was more than just a talented painter; he was a catalyst and a connector in a pivotal era for British art. His enthusiastic adoption and intelligent adaptation of Post-Impressionist principles, combined with his dedication to depicting the world around him with honesty and vibrant colour, produced a body of work that remains fresh and engaging. His role in founding and leading the Camden Town Group cemented his importance as an organizer and advocate for modernism. Though his career was cut tragically short, Gore's paintings and his influence endure, marking him as a key figure who helped shape the course of British art in the modern era. His legacy lies in his beautiful, colour-filled canvases and in the collaborative spirit he fostered among his contemporaries.