Introduction: The Artist and His Era

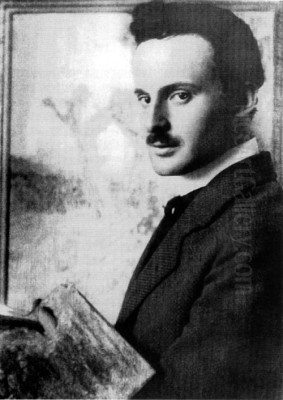

Walter Ophey stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the vibrant landscape of early 20th-century German art. Born on March 25, 1882, in Eupen (then part of Prussia, now Belgium), and passing away prematurely on January 11, 1930, in Düsseldorf, Ophey's life spanned a period of immense artistic upheaval and innovation. He emerged as a leading proponent and pioneer of Rhineland Expressionism, a distinct regional variant of the broader Expressionist movement that swept across Germany. His work, characterized by a unique synthesis of influences and a deeply personal connection to landscape, offers a fascinating window into the artistic currents that shaped modern art in Germany before and after the First World War. Ophey was not merely a painter; he was an organizer, a connector, and a vital force within the progressive art circles of Düsseldorf and the surrounding region.

Early Training and Influences in Düsseldorf

Ophey's formal artistic journey began in 1900 when he enrolled at the prestigious Kunstakademie Düsseldorf (Düsseldorf Art Academy). At the time, the Academy was still largely dominated by the traditions of 19th-century realism and history painting, though currents of change were beginning to stir. A pivotal moment in his education came in November 1904, when he joined the landscape painting class led by Eugen Dücker. Dücker, himself a respected landscape painter, represented a more atmospheric, late-Impressionist sensibility within the Academy's structure. Studying under Dücker provided Ophey with a solid foundation in landscape depiction and technique, but his own artistic inclinations soon pushed him beyond the bounds of academic tradition. He began to absorb the newer artistic ideas filtering into Germany, particularly from France.

The Düsseldorf environment, while perhaps less radical than Berlin or Munich at the time, was nonetheless becoming a crucible for new artistic thought. Ophey and his contemporaries were increasingly exposed to French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The works of artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and especially the Post-Impressionists Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin, with their emphasis on subjective experience, structural form, and expressive color, began to resonate deeply with a younger generation seeking alternatives to academic naturalism. This burgeoning interest laid the groundwork for Ophey's later innovations and his role in founding key avant-garde groups.

The Sonderbund: Forging a New Path

A crucial development in Ophey's career and the history of modern art in the Rhineland was the formation of the "Sonderbund Westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler" (Special League of West German Art Friends and Artists) in 1909. Ophey was a key founding member, joining forces with fellow artists Julius Bretz, Max Clarenbach (who had also studied under Dücker), August Deusser, and Wilhelm Schmurr. This group, initially formed in Düsseldorf, aimed to break free from the constraints of the established art institutions and exhibition systems, which they felt were resistant to modern artistic trends. Their goal was twofold: to promote the work of progressive artists from the region and to introduce the German public to the latest developments in international modern art, particularly from France.

The Sonderbund quickly became a dynamic force. They organized a series of groundbreaking exhibitions. Their initial shows focused on deepening the understanding of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The most famous and influential of these was the monumental 1912 Sonderbund exhibition held in Cologne. This exhibition was unprecedented in its scale and scope, featuring over 600 works. It provided a comprehensive overview of European modernism, showcasing not only the French pioneers like Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Henri Matisse, but also contemporaries like Pablo Picasso and Edvard Munch, alongside leading German Expressionists such as members of Die Brücke (like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner) and Der Blaue Reiter (like Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc). Ophey himself was represented in these exhibitions, positioning his work within this international avant-garde context. The Sonderbund's activities, particularly the 1912 show, were instrumental in shaping artistic discourse in Germany and even had an impact internationally, influencing events like the Armory Show in New York the following year.

Travels and Stylistic Evolution: Italy and Paris

Like many artists of his generation, travel played a crucial role in shaping Walter Ophey's artistic vision. Direct encounters with different landscapes, cultures, and artistic environments broadened his horizons and catalyzed significant shifts in his style. In the spring of 1910, he embarked on a journey to Italy. The light, colors, and landscapes of the south, as well as the rich artistic heritage, left a lasting impression. This experience likely reinforced his commitment to landscape painting but encouraged a bolder, more expressive use of color and a simplification of form, moving away from purely naturalistic depiction towards capturing the essence and feeling of a place.

An even more transformative experience was his visit to Paris in the autumn of 1911. Paris was then the undisputed center of the international art world, buzzing with radical new ideas. Ophey immersed himself in this environment, encountering firsthand the latest developments in Fauvism and Cubism. The Fauvist emphasis on intense, non-naturalistic color, championed by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, resonated with his own explorations. Simultaneously, the structural innovations of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, offered new ways of analyzing and representing form and space. Ophey absorbed these influences, integrating elements of Cubist structure and Fauvist color into his own developing style. He became particularly known for his distinctive linear approach and his masterful use of pastels, which allowed for both vibrant color and dynamic line work. His exposure to Japanese art in Paris, likely through prints, also contributed to his interest in flattened perspectives and decorative compositions.

Rhineland Expressionism: A Regional Identity

Walter Ophey is rightly considered a central figure in Rhineland Expressionism. This regional manifestation of the broader German Expressionist movement had its own distinct characteristics. While sharing the general Expressionist goal of conveying subjective emotion and inner experience over objective reality, Rhineland Expressionism, particularly as practiced by Ophey and artists like August Macke and Heinrich Nauen (both associated with the Sonderbund and later movements), often displayed a more lyrical, decorative, and less angst-ridden quality compared to the sometimes harsh intensity of Die Brücke artists in Dresden and Berlin (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff) or the spiritual and abstract explorations of the Munich-based Der Blaue Reiter group (Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, Alexej von Jawlensky).

Ophey's version of Rhineland Expressionism was deeply rooted in his observation of nature and landscape, often depicting the scenery around Düsseldorf, the Lower Rhine, and the places he visited. However, he transformed these observed realities through his unique stylistic lens. His works from the pre-war period often feature rhythmic lines, a bright, sometimes jewel-like palette, and a sense of structured composition influenced by Cubism, but always retaining a connection to the visible world. He developed a characteristic style using colored chalks (pastels), creating works on paper that possessed the vibrancy of paintings. His approach involved simplifying forms, emphasizing linear patterns, and using color expressively rather than descriptively, aiming to capture the vitality and underlying structure of the landscape. He stood alongside other key Rhineland figures like Helmuth Macke (August's cousin), Carlo Mense, and Heinrich Campendonk in forging this regional artistic identity.

The Impact of War and the Post-War Years

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 marked a profound rupture in European society and culture, and its impact on artists like Walter Ophey was significant. The war scattered artistic communities, ended collaborations like the Sonderbund (which had effectively dissolved after the 1912 Cologne exhibition), and brought personal hardship and trauma. While details of Ophey's direct wartime experience are less documented than some others, the post-war atmosphere of disillusionment, economic instability, and social change inevitably affected his life and art.

Following the war, Ophey's artistic style underwent a noticeable shift. While still rooted in Expressionism, his work generally became more structured, perhaps more restrained. The vibrant, high-keyed colors of his pre-war period often gave way to more subdued, earthy tones. The compositions became tighter, sometimes exhibiting a greater degree of formal control, reflecting perhaps a broader post-war European trend towards a "return to order" seen in the work of artists across the continent, including former Cubists like Picasso. Despite this shift towards greater structure and a more muted palette, the expressive line and his fundamental connection to landscape remained constants in his work.

Das Junge Rheinland and Continued Activity

Despite the challenges of the post-war era, Ophey remained an active figure in the Düsseldorf art scene. He was a co-founder of the artist group "Das Junge Rheinland" (The Young Rhineland), established around 1919. This group, which included artists like Arthur Kaufmann, Gert Wollheim, and briefly associated figures like Otto Dix, aimed to revitalize the avant-garde spirit in the region after the war. It provided a platform for artists working in various modern styles, continuing the progressive legacy of the pre-war Sonderbund in a new context.

In 1922, Ophey played a key role in organizing the "Erste Internationale Kunstausstellung" (First International Art Exhibition) in Düsseldorf, held at the Tietz department store. This major event aimed to re-establish international artistic connections after the isolation of the war years. Ophey himself exhibited seven works in this show, demonstrating his continued commitment to promoting modern art and his prominent position within the regional art scene. His involvement in such initiatives underscores his importance not just as a creator but also as an enabler and organizer within the artistic community.

Representative Works and Artistic Themes

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné details hundreds of Ophey's works, certain pieces are often cited as representative of his style and development. His early work Am Abend bei Eupen (Evening near Eupen) from 1908 showcases his move beyond Impressionism towards a more expressive use of color and simplified form, capturing the atmosphere of his native landscape. Belauerte Bäume mit Weg (Leafy Trees with Path) from 1910 demonstrates his engagement with Post-Impressionist ideas, possibly showing the influence of artists like Van Gogh in its dynamic lines and heightened color, while hinting at the structural concerns that would become more prominent after his Paris trip.

Throughout his career, landscape remained Ophey's primary subject. He depicted the Rhine river, the fields and forests around Düsseldorf, coastal scenes, and the landscapes encountered on his travels. His approach was never purely topographical; he sought the underlying rhythm and structure of nature, translating it into his distinctive linear and chromatic language. Even as his style evolved, incorporating elements of Cubism and later showing a post-war sobriety, the dialogue between observation and expressive transformation remained central. His numerous works in pastel are particularly noteworthy, demonstrating his mastery of the medium to achieve both luminous color and calligraphic line.

The Planetarium Mural and Nazi Persecution

In the later years of his relatively short life, Ophey received a significant public commission. During the late 1920s, he was tasked with creating a mural for the newly built Düsseldorf Planetarium. His work, titled Der Sämann (The Sower), was a monumental undertaking. While visual records of the completed mural are scarce, the theme suggests a connection to nature, growth, and perhaps cosmic cycles, fitting for its location. The creation of this mural represented a major recognition of his status within the Düsseldorf art world.

Tragically, this significant work was destroyed just a few years after Ophey's death. In 1937, the Nazi regime, in its campaign against modern art which it deemed "degenerate" ("Entartete Kunst"), ordered the removal and destruction of Der Sämann. Ophey, like many other leading modern artists in Germany – including Emil Nolde, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Beckmann, Oskar Kokoschka, and countless others – posthumously fell victim to this cultural barbarism. The destruction of the mural was a significant loss, erasing a major public work by one of the Rhineland's most important modernists. This event underscores the hostile environment faced by avant-garde art under the Third Reich.

Later Recognition and Legacy

Walter Ophey died in Düsseldorf on January 11, 1930, at the age of only 47. His relatively early death cut short a career that was still evolving. In the decades following his death, particularly with the disruptions of the Nazi era and the Second World War, his work, like that of many regional modernists, became somewhat overshadowed by the more internationally famous figures of German Expressionism based in Berlin or Munich. However, dedicated scholarship and exhibitions, particularly from the late 20th century onwards, have led to a renewed appreciation of his significant contributions.

Art historians like Stefan Kraus, through monographs and catalogue raisonné work, have meticulously documented Ophey's life and oeuvre, solidifying his position within German art history. His role in the Sonderbund, his unique stylistic synthesis of French modernism and German Expressionism, and his importance to the specific character of Rhineland Expressionism are now widely recognized. Museums in Düsseldorf, Cologne, and elsewhere in Germany hold significant collections of his work, ensuring its accessibility to new generations. An anecdote mentioned in some sources tells of his work occasionally being mistaken for that of an Italian Renaissance master, a curious misattribution that perhaps speaks to the perceived quality of line and composition in his art, even when viewed out of context.

Conclusion: An Enduring Contribution

Walter Ophey remains a vital figure for understanding the diversity and richness of German modernism. As a co-founder of the influential Sonderbund, he helped shape the reception and direction of avant-garde art in Western Germany. His travels to Italy and Paris were crucial in filtering the innovations of Fauvism and Cubism into his distinct artistic language, contributing significantly to the formation of Rhineland Expressionism. His paintings and pastels, particularly his landscapes, are celebrated for their lyrical quality, rhythmic linearity, and expressive, often luminous, use of color.

Though his career was tragically cut short, and some major works were lost to political vandalism, Walter Ophey left behind a substantial body of work that reflects both the international currents of his time and a deeply personal artistic vision. He navigated the transition from late Impressionism through the heights of Expressionism and into the more sober climate of the post-war era, creating a unique and enduring artistic legacy. His rediscovery and continued study confirm his place as a key pioneer and representative of modern art in the Rhineland and a significant contributor to the broader narrative of 20th-century German art.