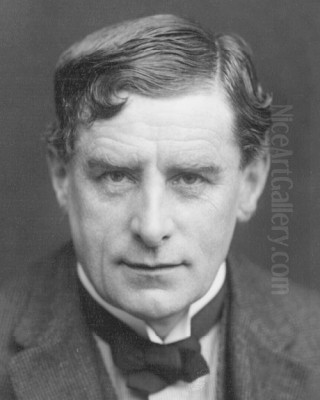

Walter Richard Sickert stands as one of the most significant, complex, and occasionally controversial figures in the landscape of British art history. Spanning the late Victorian era and the rise of modernism, Sickert's life (1860-1942) and work provide a crucial link between 19th-century traditions and the radical artistic shifts of the early 20th century. Born in Munich, Germany, he became a naturalized British citizen after his family relocated to England when he was a child. His career encompassed painting, printmaking, teaching, and writing, leaving an indelible mark on subsequent generations of artists. He was a master observer of urban life, capturing the atmosphere of London and other cities with a unique blend of realism, impressionistic technique, and psychological depth.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Walter Sickert was born on May 31, 1860, in Munich, Bavaria (now Germany). His father, Oswald Adalbert Sickert, was a Danish-German artist, and his mother, Eleanor Louisa Henry, was the illegitimate daughter of British astronomer Richard Sheepshanks, known for her earlier life involving dance. This artistic and somewhat unconventional background likely shaped Sickert's own path. In 1868, when Walter was eight, the family moved to Britain, eventually settling in London. This move led to his eventual British citizenship and cemented his identity within the British art world, despite his continental origins.

Initially, Sickert pursued a career in acting, touring with Sir Henry Irving's company for a few years. However, his true calling lay in the visual arts. He enrolled at the Slade School of Art in London for a brief period but found more formative training elsewhere. His most significant early mentorship came from the American expatriate artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Sickert became Whistler's pupil and etching assistant in 1882, absorbing his emphasis on tonal harmony, careful composition, and modern subject matter, though Sickert would eventually develop a earthier, more robust style than his master.

A pivotal moment in Sickert's development occurred during trips to Paris. In 1883, carrying a letter of introduction from Whistler, he met the French Impressionist master Edgar Degas. This encounter proved profoundly influential. Degas, known for his depictions of modern Parisian life, particularly dancers, laundresses, and café scenes, encouraged Sickert's interest in observing everyday reality and capturing fleeting moments. Degas's innovative compositional techniques, often involving unusual viewpoints and cropped figures, and his mastery of line, deeply impacted Sickert's approach to structuring his paintings and drawings. He also formed connections with other French artists, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Development of Style and Subject Matter

Sickert's artistic style evolved into a distinctive fusion of influences, primarily Whistler's tonalism and Degas's observational realism and compositional strategies, filtered through his own temperament. While often associated with British Impressionism, his work frequently employed darker, more somber palettes than typical French Impressionism, reflecting the gaslit interiors and often gritty urban environments he favored. He became a master of capturing atmosphere, whether the electric energy of a music hall or the quiet desperation of a cramped domestic interior.

His subject matter consistently focused on modern urban life, particularly in London. He was drawn to the world of popular entertainment, frequently painting scenes in music halls like the Bedford or the Old Mo (Middlesex Music Hall). Unlike many Impressionists who depicted bourgeois leisure, Sickert often focused on the performers, the architecture of the theatre, and the reactions of the working-class audience, capturing the artificial light and charged atmosphere of these venues. His paintings often convey a sense of ambiguity and psychological tension, hinting at narratives without fully revealing them.

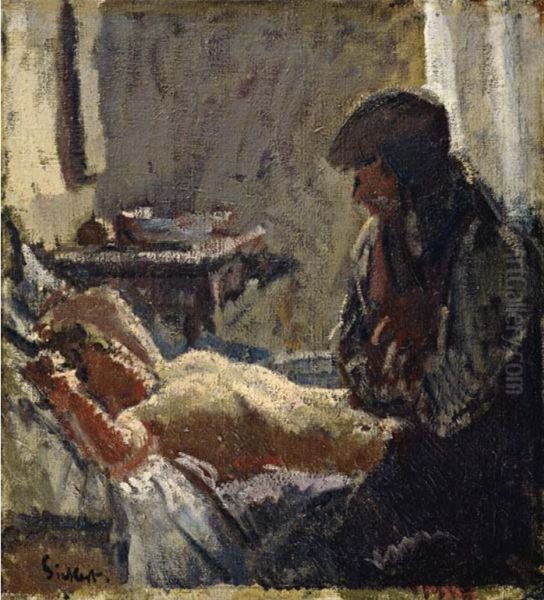

Beyond the theatre, Sickert explored the less glamorous side of city life. He painted scenes set in modest, sometimes squalid, rented rooms, particularly in areas like Camden Town. These interiors often feature solitary figures or pairs locked in ambiguous relationships, conveying themes of alienation, boredom, and introspection. He also painted cityscapes, particularly in London, Dieppe (France), and Venice, focusing on the structure and mood of the urban environment rather than picturesque views. His technique often involved working from drawings made on the spot, later developed into paintings in the studio, and increasingly, using photographs as source material.

The Camden Town Group

Sickert played a central role in the formation and direction of the Camden Town Group, a short-lived but highly influential collective of English Post-Impressionist artists. Founded in 1911, the group emerged from regular gatherings Sickert hosted at his studio at 19 Fitzroy Street. Its members aimed to depict contemporary urban life with honesty and realism, often employing bold colours and simplified forms influenced by French Post-Impressionism, particularly the work of artists like Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh.

Sickert was the elder statesman and guiding spirit of the group. Key members included Spencer Frederick Gore (the first president), Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner, Robert Bevan, and Lucien Pissarro (son of the Impressionist Camille Pissarro). They shared an interest in subjects drawn from everyday London life – street scenes, pubs, domestic interiors, portraits of ordinary people – rendered in styles that broke from the academic traditions still prevalent in Britain.

The group held only three exhibitions in 1911 and 1912 at the Carfax Gallery in London. Despite its brief existence, the Camden Town Group was crucial in introducing and popularizing modern artistic trends in Britain. Sickert's leadership and artistic vision were instrumental in defining the group's focus on realistic portrayals of the modern city, often with a focus on working-class life and interiors, rendered with techniques learned from continental modernism. The group eventually merged into the larger London Group in 1913, but its core aesthetic concerns continued to influence British art.

Key Works and Recurring Themes

Sickert's oeuvre is rich with memorable and often challenging works. Among his most famous is Ennui (c. 1914), which exists in several versions. It depicts a man and a woman in a drab interior, possibly a pub or lodging house, seemingly trapped in a state of profound boredom and alienation. The man stares blankly ahead while the woman leans away, gazing towards a painting on the wall. The work exemplifies Sickert's interest in psychological drama, ambiguous narratives, and the oppressive atmosphere of confined spaces, drawing on Victorian narrative traditions but infusing them with modern existential weight.

His music hall paintings are another significant part of his output. Works like Little Dot Hetherington at the Bedford Music Hall (c. 1888-89) or Vesta Victoria at the Old Bedford (c. 1890) capture the energy, artificiality, and sometimes the seediness of these popular entertainment venues. He often used complex perspectives, looking down from balconies or up from the stalls, incorporating architectural elements and audience members to create dynamic compositions that convey the immersive experience of the music hall. Brighton Pierrots (1915) shows his ability to handle brighter light and colour in an outdoor setting, depicting performers on the Brighton seafront with vibrancy.

Sickert did not shy away from controversial subjects. His early nude painting Katie Lawrence at Gatti's (1888), depicting a music hall performer in her dressing room, caused a stir with its unidealized realism. Later, his series known as the Camden Town Murder paintings (c. 1908-09), inspired by a real-life murder case, explored themes of violence and voyeurism in domestic settings. These works, such as L'Affaire de Camden Town, often feature clothed men and naked women in claustrophobic bedrooms, creating a disturbing and ambiguous atmosphere that continues to provoke discussion.

In his later career, Sickert increasingly relied on photographs, often sourced from newspapers or Victorian illustrations. This led to his "Echoes" series, where he translated these found images into paintings, sometimes with squared-up grid lines still visible. This technique allowed him to engage with popular culture and historical imagery in a new way, creating portraits of figures like King Edward VIII and exploring themes of celebrity and media representation, prefiguring aspects of Pop Art. His use of photography was innovative for its time and demonstrated his ongoing engagement with modern visual culture.

The Jack the Ripper Controversy

One of the most persistent and sensational aspects surrounding Walter Sickert is the recurring, though largely unsubstantiated, theory linking him to the Jack the Ripper murders that terrorized London's Whitechapel district in 1888. Sickert was known to be fascinated by the case and by crime in general. He even painted a work titled Jack the Ripper's Bedroom (c. 1907), depicting a room he purportedly rented believing it to have been occupied by the killer. This fascination, combined with the dark and sometimes unsettling nature of his Camden Town interiors, fueled speculation.

The theory gained significant public attention through the writings of crime novelist Patricia Cornwell, particularly in her book Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper—Case Closed (2002). Cornwell argued forcefully that Sickert was the Ripper, citing circumstantial evidence, interpretations of his art and letters, and controversial DNA analysis of stamps and letters (which many experts found inconclusive or flawed). She invested considerable resources in promoting her theory.

However, the vast majority of Ripper historians and art historians dismiss the claim. They point to the lack of any credible evidence directly linking Sickert to the crimes. Furthermore, Sickert's known movements and activities during the period of the murders often place him outside London, particularly in France. While his interest in the macabre is undeniable, and his art explored dark themes, this is generally seen as distinct from actual criminal involvement. The theory persists in popular culture but lacks scholarly acceptance. A related conspiracy involving a supposed illegitimate royal child, perpetuated by a man named Joseph Gorman (aka Joseph Sickert) who claimed to be Sickert's son, has also been thoroughly debunked as a hoax.

Later Career, Techniques, and Teaching

Throughout his long career, Sickert remained a prolific painter and printmaker. He continued to explore his established themes but also adapted his techniques. His later work, particularly the "Echoes" based on photographs and illustrations, showed a bolder, sometimes rougher application of paint and a continued interest in translating existing imagery into his own artistic language. He worked extensively in Dieppe, France, and Venice, Italy, capturing the unique character of these locations alongside his London scenes.

Sickert was also an influential teacher and writer on art. He taught at various art schools, including the Westminster School of Art, and ran his own private schools at different times. His teaching emphasized rigorous drawing, observation, and an understanding of tonal values. He penned numerous articles and reviews, often expressing strong opinions on art and artists with characteristic wit and insight. His writings provide valuable context for understanding his own work and the broader art scene of his time.

His personality was known to be eccentric, charismatic, and sometimes difficult. He cultivated different personas throughout his life, changing his appearance and even his name occasionally (signing works as 'Sickert' or sometimes 'Richard Sickert'). He was married three times: first to Ellen Cobden (daughter of politician Richard Cobden), then to Christine Angus, and finally to the painter Thérèse Lessore, who survived him. Despite his bohemian tendencies and complex personality, he remained a central and respected, if sometimes debated, figure in the London art world until his death.

Connections and Influence

Sickert's position in art history is defined not only by his own work but also by his extensive network of connections and his profound influence on subsequent artists. His relationships with Whistler and Degas were foundational, linking him directly to Aestheticism and French Impressionism. Through his time in France, he was aware of and absorbed lessons from Post-Impressionist artists like Gauguin and Van Gogh, whose approaches to colour and form informed the Camden Town Group's experiments. He was also connected to the New English Art Club (NEAC), an exhibiting society founded as an alternative to the Royal Academy, which included artists like Philip Wilson Steer.

His most significant impact was arguably on 20th-century British figurative painting. As a leader of the Camden Town Group, he directly influenced peers like Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner, and Robert Bevan. More broadly, his commitment to depicting modern life with psychological depth and painterly realism resonated with later generations. The Euston Road School, founded in the late 1930s by artists like William Coldstream, Victor Pasmore, and Claude Rogers, looked back to Sickert's emphasis on objective observation and tonal painting as an antidote to abstraction.

Perhaps most famously, major figures of post-war British painting acknowledged Sickert's importance. Francis Bacon was fascinated by Sickert's dark interiors and his use of photography, seeing parallels with his own explorations of the human figure in confined, psychologically charged spaces. Lucian Freud, known for his intense, realistic portraiture, also admired Sickert's unflinching observation and painterly technique. Artists like Frank Auerbach and Howard Hodgkin, while developing distinct styles, can also be seen as inheritors of Sickert's dedication to the expressive possibilities of paint and his engagement with the observed world. He remains a "painter's painter," admired by those dedicated to the challenges of figurative art.

Legacy and Art Historical Evaluation

Walter Sickert's legacy is that of a crucial transitional figure who navigated the complex currents between Victorianism and Modernism. He is often described as the last of the great Victorian narrative painters, yet simultaneously hailed as a pioneer of British modern art. He successfully absorbed the lessons of French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly from Degas, but adapted them to a distinctly British sensibility and subject matter, focusing on the nuances of London life, its entertainments, and its hidden domestic dramas.

His insistence on finding subjects in the everyday world, often in its less glamorous corners, and rendering them with psychological insight and technical skill, set a precedent for much British figurative painting in the 20th century. He demonstrated that modern art did not have to mean full abstraction; it could involve a fresh, challenging engagement with reality. His leadership of the Camden Town Group was instrumental in establishing a foothold for modern art principles in Britain.

Despite the controversies, particularly the persistent Ripper speculation, his artistic reputation remains strong. Major exhibitions continue to explore his work, reaffirming his technical mastery, his innovative use of source material (including photography), and the enduring power of his atmospheric and often unsettling images. He challenged the artistic conventions of his time, broadened the scope of acceptable subject matter for painting, and left behind a body of work that continues to fascinate viewers and inspire artists with its blend of realism, modernity, and psychological depth. He remains a cornerstone figure in the story of British art.

Conclusion

Walter Richard Sickert was more than just a painter; he was a vital force in the British art world for decades. From his early association with Whistler to his crucial relationship with Degas, and through his leadership of the Camden Town Group, he consistently pushed the boundaries of painting. His depictions of urban life, filled with atmosphere, ambiguity, and keen observation, captured a specific moment in London's history while exploring universal themes of human connection and alienation. Though sometimes overshadowed by controversy, his artistic innovations, his influence on generations of painters like Bacon and Freud, and his role in bridging 19th-century traditions with 20th-century modernism secure his place as a major and enduringly relevant figure in art history.