Ferdinand Heilbuth stands as a fascinating figure in the bustling art world of nineteenth-century Paris. Born in Germany but finding his artistic voice and citizenship in France, he navigated the complex currents flowing between academic tradition, the rise of Realism, and the revolutionary aesthetics of Impressionism. His journey from aspiring theologian to celebrated painter of modern life, landscapes, and witty clerical portraits offers a unique lens through which to view the artistic transformations of his time. Known for his technical skill, elegant compositions, and keen observation, Heilbuth carved out a successful career, earning official recognition and associating with some of the era's most pivotal artists.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

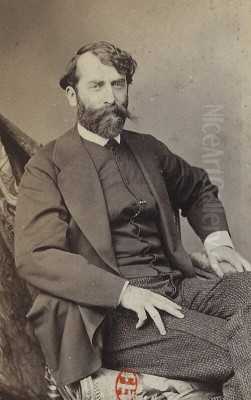

Ferdinand Heilbuth was born in Hamburg in 1826 into a Jewish family. His father served as a rabbi, and initially, young Ferdinand seemed destined to follow a similar path. He undertook theological studies, preparing for a life dedicated to religious service within the Jewish community. However, the pull of art proved stronger than the call of the rabbinate. In a decisive turn, Heilbuth abandoned his religious education around 1843.

This pivotal moment marked the beginning of his true vocation. Drawn to the vibrant artistic heart of Europe, he made his way to Paris. The French capital was then, as it remained throughout the century, the undisputed center for artistic training, innovation, and ambition. For a young man determined to become a painter, Paris offered unparalleled opportunities to learn from established masters and immerse himself in a dynamic community of fellow artists. His arrival set the stage for a complete transformation, moving from the structured world of theology to the demanding, competitive, yet liberating realm of fine art.

Academic Foundations in Paris

Upon arriving in Paris, Heilbuth sought out the best training available, enrolling in the ateliers of two prominent academic painters: Paul Delaroche and Charles Gleyre. Delaroche was renowned for his meticulously rendered historical scenes, often imbued with dramatic intensity and emotional weight. His studio emphasized precision, historical accuracy, and a polished finish, grounding students in the rigorous techniques valued by the French Académie des Beaux-Arts and the official Salon.

Charles Gleyre, a Swiss painter who had taken over Delaroche's teaching studio, offered a slightly different, though still fundamentally academic, approach. Gleyre's studio became famous not only for his instruction but also for the remarkable cohort of students who passed through it, particularly in the early 1860s. It was here that Heilbuth would have encountered fellow aspiring artists who would later form the core of the Impressionist movement, including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille. While Gleyre himself maintained a more classical style, his studio fostered a spirit of camaraderie and discussion among these young talents.

Heilbuth absorbed the lessons of his masters, developing a strong technical foundation. His early works reflected this academic training, often focusing on historical subjects or genre scenes executed with the detailed realism and narrative clarity favored by the Salon, the official exhibition venue that dominated the Parisian art world. He began exhibiting at the Salon relatively early, reportedly making his debut around 1852 and starting to gain recognition.

He achieved notable success within the Salon system, earning a third-class medal in 1852, followed by a second-class medal in 1857. He continued to receive accolades, securing a third-class medal again in 1859 and another second-class medal in 1861. These awards signified official approval and helped establish his reputation as a skilled and promising painter within the competitive Parisian art scene. His early career demonstrated a mastery of the prevailing academic style, laying the groundwork for his later evolution.

The Shift Towards Modernity

While Heilbuth initially found success with historical and romantic genre scenes, the artistic landscape of Paris was undergoing significant change during the mid-nineteenth century. The influence of Realism, championed by artists like Gustave Courbet, challenged the dominance of idealized historical and mythological subjects. Realism called for artists to depict the world around them, focusing on contemporary life, ordinary people, and unembellished landscapes.

Heilbuth proved receptive to these shifting currents. Around the late 1850s and increasingly through the 1860s, his focus began to move away from purely historical narratives. He started exploring subjects drawn from contemporary life, reflecting a growing interest in observing and rendering the social fabric and environments of his time. This transition was not abrupt but represented a gradual evolution in his thematic concerns and artistic approach.

This shift also involved a change in style. While retaining the technical polish learned in the academic studios, his work began to show a greater interest in naturalism and direct observation. The influence of Édouard Manet, a pivotal figure who bridged Realism and Impressionism, became particularly important for Heilbuth, especially in his exploration of lighter color palettes and the effects of natural light. Manet's bold depictions of modern Parisian life and his innovative techniques encouraged many artists, including Heilbuth, to break from purely academic conventions.

Heilbuth's move towards contemporary subjects and a brighter, more observational style positioned him alongside other artists who were seeking new ways to represent the modern world. He was adapting his skills to new themes, finding inspiration not just in the past, but in the present day – in the streets, parks, and social gatherings of Paris and its surroundings.

Mastering Genre and Society

One of Heilbuth's most significant early works demonstrating his engagement with contemporary social themes is Le Mont-de-Piété (The Pawnshop), painted around 1861. This painting, now housed in the prestigious Musée d'Orsay (having entered the Louvre collections earlier), depicts the waiting room of a state-run pawnshop in Paris. It offers a poignant glimpse into the lives of ordinary Parisians facing economic hardship, showcasing Heilbuth's skill in capturing character and atmosphere with sensitivity and realism. The work was exhibited at the Salon of 1861, where it received considerable attention and contributed to his growing reputation.

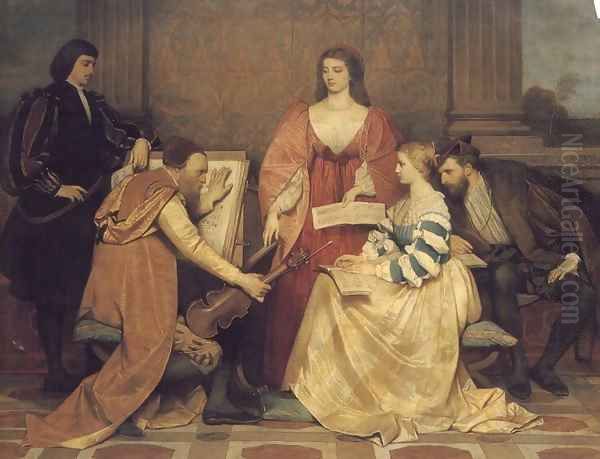

Beyond scenes of social realism, Heilbuth also became known for his depictions of elegant Parisians enjoying leisure activities, often in outdoor settings. He painted scenes of figures strolling in parks, boating on the Seine, or gathering for social events. These works captured the fashionable side of modern life, rendered with a characteristic grace and charm. His painting Fête dans les jardins du château (Festival in the Castle Gardens), dated 1863, exemplifies this aspect of his oeuvre, showcasing his ability to handle complex group compositions and convey a sense of refined sociability.

In these depictions of contemporary leisure and society, Heilbuth's work sometimes invites comparison with that of James Tissot, another artist who excelled at portraying the fashionable world of Paris and London. Both artists shared an eye for detail, particularly in rendering clothing and capturing the nuances of social interaction. However, Heilbuth often maintained a slightly softer, more painterly touch, increasingly influenced by the plein-air (outdoor painting) practices gaining traction at the time. His society paintings blended careful observation with an appealing elegance, contributing to his popularity among collectors.

Embracing the Landscape

Concurrent with his exploration of modern genre scenes, Heilbuth developed a strong interest in landscape painting, particularly from the late 1860s onwards. This shift aligned with a broader movement in French art, where landscape evolved from being merely a backdrop for historical or mythological narratives to becoming a subject worthy of depiction in its own right. The Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Charles-François Daubigny, had already paved the way by emphasizing direct observation of nature and capturing atmospheric effects.

Heilbuth embraced landscape painting with enthusiasm, developing a style characterized by brighter colors, a more fluid brushstroke, and a keen sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He was particularly drawn to waterside scenes, frequently painting the banks of the Seine and other rivers near Paris. These locations offered rich opportunities to study the interplay of light on water, reflections, and the lushness of riverside vegetation.

His work By the Waterside (Au Bord de l'Eau), exhibited at the Salon of 1870, is a prime example of his landscape focus during this period. Significantly, this painting depicted La Grenouillère, a popular boating and bathing spot on the Seine near Bougival. This location was famously painted by Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir around the same time (1869), becoming an iconic site for early Impressionist experimentation with capturing fleeting effects of light and water. Heilbuth's treatment of the scene, while perhaps retaining more structure than the radical canvases of Monet and Renoir, clearly shows his engagement with similar concerns: capturing the vibrancy of outdoor light and the leisurely atmosphere of a modern recreational spot.

His landscapes often feature figures integrated naturally into the setting, enjoying the scenery or engaged in quiet activities. The overall effect is one of tranquility and charm, rendered with an increasingly luminous palette and a touch that suggests the influence of Impressionist techniques, even if he never fully adopted their broken brushwork or dissolved forms. His dedication to landscape painting marked a significant part of his artistic identity in his later career.

The London Interlude

The course of Heilbuth's life and career was briefly interrupted by political turmoil. When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870, leading to the siege of Paris, many artists and residents fled the city. Heilbuth, being of German origin (though living and working in Paris for decades), found it prudent to leave France during the conflict. He sought refuge in London, joining a number of other French artists, including Monet, Pissarro, and Daubigny, who also spent time in the British capital during the war.

During his stay in London, Heilbuth continued to paint and exhibit his work. He showed pieces at prestigious venues like the Royal Academy of Arts and the Grosvenor Gallery. This period exposed him to the British art scene, potentially bringing him into contact with artists like James Abbott McNeill Whistler, another cosmopolitan figure known for his aesthetic sensibilities and tonal harmonies. While the direct influence of this London sojourn on his style is debated, it provided continuity for his career during a difficult period and broadened his exhibition history beyond France.

Upon the conclusion of the war and the suppression of the Paris Commune in 1871, Heilbuth returned to Paris, the city he considered his artistic home. He resumed his place in the Parisian art world, his reputation intact and perhaps even enhanced by his international exposure. The experience underscored his deep connection to Paris, while the time away may have offered fresh perspectives that subtly informed his subsequent work.

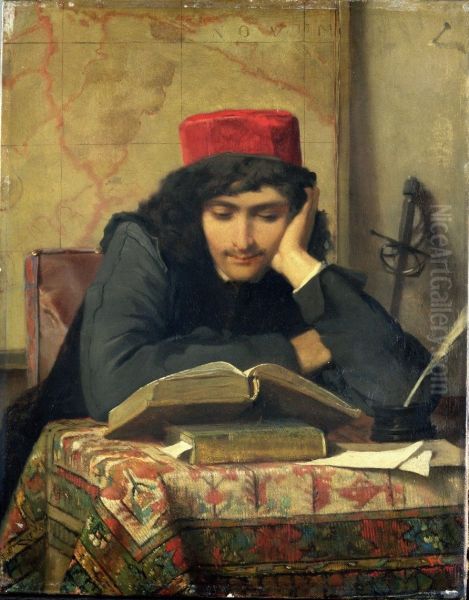

The Painter of Cardinals

Alongside his landscapes and scenes of modern life, Ferdinand Heilbuth developed a particular and rather unique specialty: paintings featuring Roman Catholic cardinals. This recurring theme earned him the nickname "le peintre des cardinaux" (the painter of cardinals). These works often depicted high-ranking clergymen in moments of leisure or quiet contemplation, sometimes set within opulent interiors or serene gardens.

Heilbuth approached these subjects with his characteristic technical finesse and observational skill. He rendered the rich textures of the cardinals' scarlet robes and the details of their surroundings with meticulous care. However, these paintings were often imbued with a subtle wit or gentle irony. Rather than portraying the cardinals solely in solemn religious contexts, he frequently showed them engaged in everyday activities – examining objets d'art, taking tea, strolling, or relaxing – highlighting their human side, sometimes with a hint of worldliness or gentle satire.

This niche proved highly successful. The paintings were popular with collectors, perhaps appealing due to their combination of fine execution, intriguing subject matter, and a touch of sophisticated humor. They stood out from his other work and contributed significantly to his fame. While seemingly different from his landscapes or scenes of Parisian society, the cardinal paintings shared Heilbuth's consistent interest in observing human character and behavior, albeit within a very specific milieu. His ability to capture the demeanor and atmosphere surrounding these powerful figures of the Church showcased his versatility as a painter.

Impressionist Connections and Influence

Ferdinand Heilbuth occupied an interesting position relative to the Impressionist movement. Having studied alongside Monet, Renoir, and Sisley in Gleyre's studio, he knew the key figures personally. He maintained connections with them and other progressive artists, including the influential Édouard Manet. Manet's impact is often cited, particularly regarding Heilbuth's adoption of lighter palettes and his interest in capturing the nuances of contemporary light.

Heilbuth associated with these artists and shared their interest in modern subjects and plein-air painting. His landscapes, especially those from the 1870s onwards, clearly show an awareness of Impressionist concerns with light, color, and atmosphere. Works depicting scenes along the Seine, like By the Waterside, place him geographically and thematically close to the heart of early Impressionism. He was also friends with artists like Luigi Chialiva and was welcomed in the artists' colony at Ecouen, indicating his integration into various artistic circles.

However, Heilbuth never fully embraced the radical techniques that defined core Impressionism. He generally retained a more solid sense of form and a smoother finish than artists like Monet or Pissarro, whose broken brushwork and dissolution of outlines were central to their style. He did not participate in the independent Impressionist exhibitions, preferring to continue showing his work at the official Salon, where he had already established a successful career.

Therefore, Heilbuth is best understood as an artist who operated skillfully between the established academic world and the emerging avant-garde. He absorbed influences from Impressionism, incorporating lighter colors and a focus on atmospheric effects into his work, but adapted these elements to fit within a framework that remained accessible and appealing to the Salon audience and mainstream collectors. He represents a significant group of artists from the period who navigated this middle ground, contributing to the overall modernization of French painting without fully breaking from tradition.

Recognition and Later Career

Ferdinand Heilbuth's talent and success did not go unrecognized by the French establishment. His consistent participation and awards at the Paris Salon built a solid reputation. This was further cemented by official honors bestowed upon him by the French government. In 1861, he was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the prestigious Legion of Honor, a significant mark of distinction for an artist. His status was elevated further in 1881 when he was promoted to the rank of Officier (Officer) within the same order.

His connection to France deepened over the years. Having lived and worked primarily in Paris since the 1840s, he formalized his ties by becoming a naturalized French citizen in 1876. This step solidified his identity as a French artist, despite his German origins. He maintained a studio in Paris, reportedly on the Rue de la Rochefoucauld, and continued to be an active participant in the city's art life.

Beyond the Paris Salon, Heilbuth's work gained international exposure. As noted, he exhibited in London during the Franco-Prussian War, showing at the Royal Academy and the Grosvenor Gallery. His paintings also found audiences in the United States, with exhibitions recorded at venues like the Boston Athenaeum. This international presence indicates the broad appeal of his work during his lifetime. He continued to paint prolifically through the 1870s and 1880s, refining his characteristic subjects – elegant landscapes, scenes of modern leisure, and his popular cardinal paintings – until his death.

Ferdinand Heilbuth passed away in Paris in 1889, at the age of 63. He left behind a substantial body of work that reflected his successful navigation of the complex art world of his time, earning him both critical acclaim and official honors within his adopted homeland.

Artistic Style Summarized

Ferdinand Heilbuth's artistic style is characterized by its blend of academic training and responsiveness to contemporary artistic developments, particularly Realism and Impressionism. His early work adhered more closely to the Romantic and historical genre painting traditions favored by his teachers, Delaroche and Gleyre, emphasizing narrative clarity, detailed rendering, and a polished finish.

As his career progressed, his style evolved significantly. He adopted a brighter color palette, influenced partly by his association with Manet and the Impressionists. His brushwork became somewhat looser and more fluid, especially in his landscapes, although he generally retained a greater degree of definition and finish than the core Impressionists. He developed a keen eye for capturing the effects of natural light and atmosphere, particularly evident in his numerous waterside scenes.

His subject matter was diverse, ranging from the social realism of Le Mont-de-Piété to elegant depictions of Parisian society at leisure, tranquil landscapes often featuring the Seine, and his unique, often witty paintings of cardinals. Across these varied themes, his work consistently displays technical skill, compositional elegance, and a talent for observing and conveying character and mood. His style can be described as graceful, charming, and sophisticated, bridging the gap between traditional craftsmanship and modern sensibilities.

Legacy and Art Historical Assessment

In his time, Ferdinand Heilbuth was a highly regarded and successful artist. He achieved recognition through Salon medals and prestigious state honors like the Legion of Honor. His works were sought after by collectors, and his paintings, such as Le Mont-de-Piété, entered major public collections like the Louvre (now Musée d'Orsay). His ability to capture modern life with elegance and his popular cardinal paintings secured his fame during his lifetime.

In the broader sweep of art history, Heilbuth is often viewed as a talented practitioner who successfully navigated the transition from academicism towards modernity, but who stopped short of the radical innovations of the Impressionist avant-garde. He is seen as an important figure for understanding the diversity of the Parisian art scene in the latter half of the nineteenth century – an artist who absorbed new ideas about light, color, and subject matter but adapted them into a style that retained broader appeal.

While perhaps overshadowed in historical narratives by more revolutionary figures like Monet, Manet, or Degas, Heilbuth's work remains significant. His paintings offer valuable insights into the social life, leisure activities, and landscapes of his era. His particular niche depicting cardinals provides a unique commentary on religious figures within contemporary society. His career demonstrates that the path towards modern art was not monolithic, involving many artists who forged individual paths blending tradition and innovation. His works continue to be appreciated for their technical skill, charm, and evocative portrayal of nineteenth-century life.

Conclusion

Ferdinand Heilbuth's artistic journey took him from the prospect of a religious life in Hamburg to the heart of the Parisian art world, where he became a respected French painter. Trained in the academic tradition by masters like Delaroche and Gleyre, he evolved his style to embrace the subjects and techniques of modern art, influenced by Realism and his connections with Impressionist pioneers like Monet and Manet. He excelled in depicting contemporary society, tranquil landscapes, and his signature witty portrayals of cardinals. Awarded high honors and achieving French citizenship, Heilbuth carved out a distinct and successful career, bridging artistic worlds. His work remains a testament to his skill and provides a valuable window onto the multifaceted art scene of late nineteenth-century France.