James Stuart Park stands as a significant figure in late 19th and early 20th-century Scottish art. Born in 1862 and passing away in 1933, Park carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming renowned primarily for his evocative and beautifully rendered paintings of flowers. Though associated with the burgeoning art scene in Glasgow, particularly the group known as the Glasgow Boys, he maintained a unique focus. His work, characterized by a distinctive technique and a deep appreciation for the transient beauty of blooms, found considerable favour among collectors and continues to be admired for its sensitivity and painterly quality. This exploration delves into the life, art, and legacy of a painter who dedicated his career to capturing the luminous essence of flowers.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

James Stuart Park entered the world in 1862 in Kidderminster, Worcestershire, England, though his roots lay firmly in Scotland, with parents hailing from Ayrshire. This Scottish connection would prove central to his life and artistic career. His early artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training, a path typical for aspiring artists of his generation. He enrolled at the prestigious Glasgow School of Art, an institution that was becoming a crucible for new artistic ideas and talent in Scotland, fostering an environment distinct from the more established Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh.

Seeking to broaden his horizons and refine his skills further, Park travelled to Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world at the time. This period was crucial for many artists from Britain and beyond, offering exposure to both rigorous academic training and the revolutionary currents of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. In Paris, Park studied under respected academic painters, including Jules Joseph Lefebvre, Gustave Boulanger, and Fernand Cormon. These masters, known for their technical proficiency and adherence to classical principles, would have provided Park with a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and paint handling, even if his later style diverged significantly from strict academicism.

Park commenced his professional career around 1888. Initially, like many artists seeking commissions and recognition, he focused on portraiture. Portraits offered a relatively reliable source of income and prestige. However, reports suggest that financial difficulties prompted a significant shift in his artistic direction. Whether driven purely by economic necessity or a combination of factors including a genuine passion for the subject, Park began to concentrate increasingly on flower painting. This decision proved fortuitous, leading him to the genre where he would make his most lasting contribution.

The Art of the Flower: Subject and Style

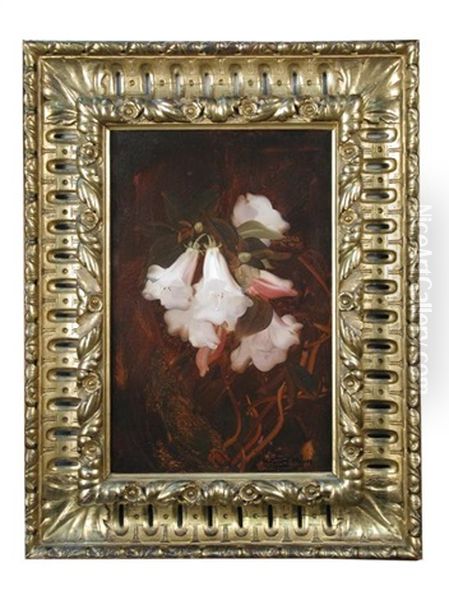

Stuart Park's name became synonymous with floral still life. He developed an extraordinary affinity for depicting flowers, particularly roses, lilies, orchids, and azaleas. His approach was not one of meticulous botanical illustration, although a sensitivity to the structure and character of each bloom is evident. Instead, Park sought to capture the spirit, texture, and luminous quality of the flowers, often presenting them in simple arrangements against dark, atmospheric backgrounds. This contrast became a hallmark of his work, making the vibrant colours and delicate forms of the petals appear almost to glow.

His technique was distinctive and diverged from the smooth, highly finished surfaces often favoured in academic painting. Park employed relatively broad, confident, and often rapid brushstrokes. This painterly approach, sometimes described as using "rough" or "square" touches of paint, allowed him to suggest form and texture rather than delineating every detail precisely. He was more concerned with the overall effect, the play of light across the petals, and the inherent beauty of the colours themselves. This method imbued his paintings with a sense of immediacy and vibrancy, conveying the freshness and fragility of the blooms.

Park's palette often emphasized the creamy whites, soft pinks, rich yellows, and deep reds of the flowers he depicted, set against deep, often indeterminate backgrounds of brown, green, or near-black. This use of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – heightened the visual impact and focused the viewer's attention entirely on the floral subject. His compositions were typically straightforward, focusing on a cluster of blooms, sometimes in a simple vase, allowing the flowers themselves to be the undisputed stars of the canvas. Works titled simply Roses, White Lilies, or Still Life with Roses are characteristic of his output.

The period between roughly 1889 and 1892 is often cited by critics and historians as the time when Park produced his finest work. During these years, his technique was perhaps at its most fresh and expressive, particularly in his studies of pink, yellow, and red roses. While he continued to paint flowers throughout his career, some observers noted that his later work occasionally became somewhat more formulaic, though it retained its popular appeal. Nonetheless, his best paintings from this peak period are considered masterpieces of the genre within Scottish art.

Influences and Artistic Context

Stuart Park's artistic development did not occur in a vacuum. Like all artists, he absorbed influences from various sources. His time in Paris exposed him to contemporary French art, although his style doesn't directly mirror French Impressionism in the manner of some other artists. However, the emphasis on light, colour, and capturing fleeting effects, central tenets of Impressionism, may have resonated with him and informed his looser brushwork and focus on visual sensation over strict representation.

A more direct and acknowledged influence on Park, as well as many of his contemporaries in Glasgow, was the art of Japan, particularly Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Japonisme, the European fascination with Japanese art and aesthetics, swept through artistic circles in the latter half of the 19th century. Artists like James McNeill Whistler, whose work was known and admired in Glasgow, championed Japanese principles of design, composition, and colour. Aspects such as flattened perspectives, asymmetrical arrangements, and a focus on decorative qualities, found in Japanese art, subtly informed the work of several Glasgow artists, including E.A. Hornel and George Henry. While Park's connection might seem less overt, the emphasis on bold shapes, colour harmony, and the decorative potential of natural forms in his work can be seen as reflecting this broader trend.

Within the context of flower painting, Park's work can be compared and contrasted with that of other specialists. The French painter Henri Fantin-Latour, for instance, was renowned for his exquisite, detailed, and often more formally arranged flower paintings, which were highly popular in Britain. Park's approach was generally looser and more focused on texture and light than Fantin-Latour's meticulous realism. Park's dedication to the genre, however, places him within this significant tradition of still life painting.

His immediate context was, of course, the vibrant art scene of Glasgow. He operated alongside the Glasgow Boys, a group challenging the conservative norms of the Scottish art establishment. While his subject matter differed from their frequent focus on rural realism and landscape, his painterly technique and interest in colour aligned with their general ethos. His work shared a certain modernity and a move away from tightly rendered Victorian narrative painting.

Connection to the Glasgow Boys

James Stuart Park's relationship with the Glasgow Boys is an important aspect of his career, though nuanced. He was not typically considered one of the core members of the group, which included figures like Sir James Guthrie, Sir John Lavery, George Henry, E.A. Hornel, Arthur Melville, E.A. Walton, and Joseph Crawhall. These artists were primarily known for their plein-air landscapes, scenes of rural life, and innovative use of colour and technique, often influenced by French Realism (especially Jules Bastien-Lepage) and Impressionism.

Despite not being central to the group's formation or its primary thematic concerns, Park was closely associated with them. He exhibited frequently alongside the Glasgow Boys at venues like the Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts (G.I.). His work shared certain stylistic affinities with theirs, particularly the emphasis on bold brushwork, the exploration of colour and tone, and a general rejection of overly sentimental or anecdotal subject matter in favour of visual aesthetics. His focus on still life provided a different dimension to the broader output associated with the Glasgow School.

His association proved beneficial. The Glasgow Boys were gaining significant recognition both nationally and internationally during the late 1880s and 1890s, and exhibiting alongside them likely enhanced Park's visibility. His paintings found a ready market, particularly in the West of Scotland, where the new styles championed by the Glasgow artists were finding favour among progressive collectors. Sources note that his works sold well and relatively quickly, indicating his popularity within this milieu. While artists like Guthrie and Lavery achieved greater international fame, Park secured a strong regional reputation, becoming a respected figure within the Glasgow art community. Other artists associated with the Glasgow School, such as Alexander Roche or David Gauld, also explored different subjects while sharing the general painterly ethos.

Exhibitions, Reception, and Market

Throughout his career, James Stuart Park was a regular exhibitor at major Scottish institutions. His work frequently appeared at the Royal Scottish Academy (R.S.A.) in Edinburgh and, perhaps more significantly given his base, at the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts (G.I.). These annual exhibitions were crucial platforms for artists to showcase their work, gain critical attention, and attract buyers. Park's consistent presence at these venues indicates his active participation in the professional art world of his time.

His flower paintings proved particularly popular with the public and collectors in Glasgow and the surrounding region. There was a strong market for decorative paintings, and Park's works, with their appealing subject matter and attractive execution, fit this demand well. Contemporary accounts suggest his exhibitions were often commercially successful, with paintings being sold readily. While perhaps initially available at relatively modest prices, the value of his work increased as his reputation grew.

Art critics acknowledged the quality and distinctiveness of his style. His ability to capture the texture and luminosity of petals using bold, suggestive brushwork was often noted. The contrast between the brightly lit flowers and the dark, atmospheric backgrounds was seen as particularly effective, lending his works a dramatic and decorative quality. Some interpretations also touch upon the memento mori aspect inherent in floral painting – the capturing of transient beauty, a reminder of the fleeting nature of life. This adds a layer of potential meaning beyond the purely decorative.

While highly regarded within Scotland, Park's reputation did not achieve the same international reach as some of the leading Glasgow Boys like Lavery or Guthrie, or indeed later Scottish artists like the Colourists Samuel John Peploe or F.C.B. Cadell, who also excelled in still life but with a brighter, more Fauvist-influenced palette. Park's focus remained largely domestic. However, within Scotland, his contribution was, and continues to be, recognized.

Later Life and Legacy

In his later years, James Stuart Park moved from Glasgow to Kilmarnock, in his parents' home county of Ayrshire. He continued to paint, living in Kilmarnock for many years until his death there in 1933, at the age of 71. He remained dedicated to his chosen subject, leaving behind a substantial body of work focused almost entirely on the depiction of flowers.

Today, James Stuart Park is remembered as a distinctive and accomplished painter within the context of the Glasgow School and Scottish art history more broadly. While perhaps overshadowed internationally by contemporaries who tackled grander themes or landscapes, his specialization allowed him to develop a unique and highly personal style. His flower paintings are admired for their technical skill, their sensitivity to light and texture, and their sheer decorative beauty. He successfully translated the painterly concerns of his generation – the interest in bold brushwork, colour, and capturing visual effects – into the genre of still life.

His works are held in numerous public collections across Scotland, including the National Galleries of Scotland, Glasgow Museums Resource Centre (which holds a significant number of works associated with the Glasgow Boys), the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow, and various regional galleries. This presence in public collections ensures his art remains accessible and affirms his status as an important figure in the nation's artistic heritage. His paintings also continue to be popular on the art market, appreciated by collectors who value his unique contribution to floral painting. He stands alongside artists like William McTaggart, who represented an older generation of Scottish landscape painting, and contemporaries like E.A. Walton or Joseph Crawhall, as part of the rich tapestry of Scottish art at the turn of the century. Even later artists like Anne Redpath, known for her vibrant still lifes, worked within a tradition that Park contributed to.

Conclusion

James Stuart Park dedicated his artistic life to the beauty of flowers. Emerging from the dynamic environment of the Glasgow School of Art and Parisian ateliers, he navigated away from portraiture to find his true calling in floral still life. His distinctive style, marked by bold, textural brushwork and a dramatic use of light against dark backgrounds, captured the luminous essence of blooms like roses and lilies with remarkable sensitivity. Though closely associated with the Glasgow Boys, he pursued his own specialized path, achieving significant recognition and popularity, particularly within Scotland. His works remain a testament to his unique vision and technical skill, securing his place as a significant Scottish painter who found enduring artistry in the transient beauty of the flower. His legacy lies in these evocative canvases, which continue to charm and engage viewers today.