Margherita Caffi stands as a significant figure in the history of Italian Baroque art, celebrated for her vibrant and dynamic still-life paintings. Active primarily in Northern Italy during the latter half of the 17th and the early 18th centuries, she carved out a successful career in a field largely dominated by men, leaving behind a legacy of works characterized by their energetic brushwork, rich colours, and dramatic compositions. Her specialization in floral and fruit still lifes placed her within a popular genre, yet her distinctive style set her apart from many contemporaries.

Born around 1650, likely in Cremona or Milan, and passing away in Milan in 1710, Caffi's life spanned a period of flourishing artistic activity in Italy. While precise details of her early training are debated, her artistic environment was undoubtedly formative. She emerged from a family with artistic inclinations, providing a foundation upon which she built her remarkable career, achieving recognition and patronage that testified to her exceptional talent.

Artistic Roots and Family Ties

Margherita Caffi's immersion in the art world began at home. Her father was Vincenzo Volò, himself a noted still-life painter often referred to as ‘Vincenzino dei fiori’ (Vincenzino of the flowers). Active in Milan, Vincenzo specialized in floral compositions, and it is highly probable that Margherita received her initial instruction from him, absorbing the fundamentals of the still-life genre that was gaining popularity across Europe. This familial connection provided both training and access to the artistic milieu of Lombardy.

Further cementing her connection to the art world, Margherita married Ludovico Caffi, another still-life painter, originally from Cremona but active in Piacenza, where the couple eventually settled. Ludovico also specialized in still lifes, though his style is generally considered distinct from Margherita's more exuberant approach. This union created a household deeply involved in artistic production, likely fostering an environment of mutual support and perhaps even collaborative exchange, although Margherita's individual artistic identity remained strong and recognizable.

Despite this artistic lineage, some accounts emphasize Margherita Caffi as being largely self-taught. This likely refers less to a complete lack of formal instruction and more to the development of her highly personal and innovative style. While she would have learned techniques from her father and possibly her husband, the dynamism, bold colour contrasts, and fluid brushwork that define her mature work suggest a significant degree of independent exploration and stylistic evolution, moving beyond conventional approaches.

The family established themselves in Piacenza, and records indicate they had children. Balancing family life with a demanding artistic career was a challenge for women of the era, making Caffi's sustained productivity and eventual fame all the more noteworthy. Her ability to navigate these demands while developing a distinct artistic voice speaks volumes about her determination and skill.

The Signature Style of Margherita Caffi

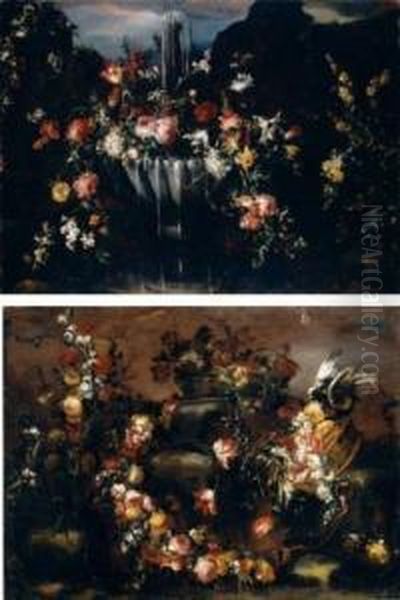

Margherita Caffi's paintings are immediately recognizable for their vitality and decorative flair. She specialized almost exclusively in still lifes, focusing predominantly on flowers and, to a lesser extent, fruit. Her approach diverged significantly from the meticulous, highly detailed realism often associated with Northern European still-life painters like Jan Brueghel the Elder or Daniel Seghers, whose works were known and admired in Italy.

Instead, Caffi embraced a more painterly technique, characterized by rapid, visible brushstrokes – a style sometimes described using the Italian term 'pittura di tocco' (painting of touch). This technique involved applying paint quickly and often thickly (impasto), creating texture and capturing the fleeting vibrancy of her subjects rather than rendering every petal or leaf with microscopic precision. This approach lent her work an energy and immediacy that was highly appealing.

Colour was central to Caffi's art. She employed a rich and often dramatic palette, favouring strong contrasts. Luminous whites, vibrant pinks, deep reds, sunny yellows, and rich blues burst forth from often dark, undefined backgrounds. This use of chiaroscuro, the dramatic interplay of light and shadow, heightened the visual impact of her compositions, making the flowers and fruit appear almost to tumble out of the darkness towards the viewer. Artists like Caravaggio had popularized dramatic lighting earlier in the century, and its influence, adapted to the still-life genre, can be felt in Caffi's work.

Her compositions were typically dynamic and asymmetrical. Rather than arranging flowers in stiff, formal bouquets, Caffi often depicted them spilling energetically from baskets, vases, or urns, or woven into lush garlands. Tulips, roses, carnations, peonies, anemones, and other blooms are rendered with a sense of movement and life. This dynamism distinguishes her work from the more static arrangements favoured by some of her Italian contemporaries, such as the meticulous compositions of musical instruments by Evaristo Baschenis or the works of Bartolomeo Bettera.

Themes and Representative Works

The core theme of Margherita Caffi's oeuvre was the celebration of nature's bounty, captured at its peak of beauty. Flowers, with their inherent associations of transience and beauty, were her primary subject. She painted bouquets in various containers – simple glass vases, ornate metal urns, or rustic woven baskets – allowing her to explore different textures and reflections alongside the organic forms of the flowers.

Among her known works, several exemplify her characteristic style. Paintings titled Still Life with Tulips, Roses, and Other Flowers in a Glass Vase or Basket of Flowers are common attributions found in major collections like the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan, and the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, also in Milan. These works typically showcase her vibrant palette, energetic brushwork, and dynamic composition, often against a dark background.

Another recurring motif in her work is the floral garland or swag. These compositions, often featuring a dense arrangement of intertwined flowers and foliage seemingly suspended or draped across the canvas, allowed for complex, flowing designs and a rich interplay of colours and forms. These decorative pieces were highly sought after for adorning interiors.

While flowers dominated, Caffi also painted fruit, sometimes integrating it with floral arrangements or presenting it separately. Grapes, peaches, figs, and pomegranates appear in her work, rendered with the same attention to colour, light, and texture. The Natura morta (Still Life) mentioned in auction records likely falls into one of these categories, showcasing her consistent focus on organic subjects.

Her works were not merely decorative; they tapped into the rich tradition of floral symbolism, although her primary focus seems to have been on the aesthetic and sensory appeal of her subjects. The sheer visual delight offered by her paintings – the explosion of colour, the sense of movement, the tactile quality of the paint – was central to their popularity.

Patronage, Recognition, and Collaborations

Margherita Caffi achieved considerable success during her lifetime, gaining recognition not only in Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna but also attracting prestigious patrons. Her skill brought her to the attention of powerful families, including the Medici in Florence. Records indicate she spent time working in Florence and received commissions from Vittoria della Rovere, Grand Duchess of Tuscany and wife of Ferdinando II de' Medici. Securing patronage from such influential figures was a significant accomplishment, particularly for a female artist in the 17th century.

Her works were highly valued and appeared in prominent collections and inventories of the period. This commercial and critical success demonstrates that her vibrant, decorative style resonated with the tastes of Baroque collectors. Her paintings were sought after for palaces and villas, adding touches of colour and natural beauty to opulent interiors. The fact that her works were collected in regions like Lombardy, Emilia, and Tuscany speaks to her widespread reputation.

Evidence also points to collaborations with other artists. Notably, she is documented as having painted the floral elements or background for a work titled Flora by the Milanese painter Federico Bianchi (c. 1635–1719). Bianchi was known for his historical and allegorical paintings. Such collaborations were not uncommon, allowing artists to leverage their respective specializations. This particular instance highlights Caffi's recognized expertise in floral painting, deemed worthy of complementing the work of an established figure painter.

Her success placed her among a growing, though still small, number of recognized female artists in Italy. While perhaps not achieving the same level of dramatic narrative power as earlier figures like Artemisia Gentileschi, or the widespread fame of her Bolognese contemporary Elisabetta Sirani, Caffi excelled within her chosen genre, demonstrating that women could achieve professional success and artistic renown in the competitive Italian art world. Her northern contemporary, Rachel Ruysch, achieved similar fame for flower painting in the Netherlands.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

Margherita Caffi worked within a rich artistic landscape. The Baroque period in Italy saw continued innovation in various genres. Still-life painting, while sometimes considered lower in the hierarchy of genres than history painting, flourished, particularly in regions like Lombardy, Naples, and Rome.

In Lombardy, Caffi's style relates to a regional tradition characterized by a certain naturalism combined with decorative richness. Artists like Evaristo Baschenis, famous for his meticulous still lifes of musical instruments, represented a different facet of Lombard still life, focusing on precision and complex arrangements. Bartolomeo Bettera worked in a similar vein to Baschenis. Caffi’s looser, more colourful approach offered a vibrant alternative.

In Rome, Mario Nuzzi, known as 'Mario de' Fiori', was a leading flower painter whose work influenced many. Further south, the Neapolitan school of still life produced masters like Paolo Porpora and Giuseppe Recco, known for their dramatic compositions often featuring fish and foodstuffs alongside flowers. The Flemish painter Abraham Brueghel was also active in Italy, bringing Northern influences. Caffi's work, while distinctly Italian and Lombard in flavour, participated in this broader European fascination with still life.

Her connection to Florence through Medici patronage also places her within the context of Tuscan art, although her style remained rooted in her Northern Italian origins. Later, in Venice, where her works were also collected, artists like Francesco Guardi would dominate the scene with veduta (view paintings), representing a shift in taste towards the Rococo and cityscape painting, though the appreciation for decorative still lifes continued.

Caffi's energetic style can be seen as part of a broader Baroque interest in dynamism, emotion, and sensory experience. While applied to the intimate scale of still life, her paintings possess a theatricality and vibrancy that align with the broader aesthetic currents of the age, exemplified in the grander schemes of artists like Luca Giordano or Andrea Pozzo.

Later Life and Lasting Legacy

Margherita Caffi continued to paint actively into the early 18th century. She passed away in Milan in 1710, leaving behind a substantial body of work that cemented her reputation as one of the leading Italian still-life painters of her generation. Her death marked the end of a career characterized by artistic innovation, professional success, and a unique ability to infuse the traditional genre of still life with extraordinary energy and colour.

Her influence can be traced in the work of later Lombard painters, and her paintings continued to be appreciated by collectors. Although, like many Baroque artists, her fame may have waned during periods of shifting artistic tastes (such as the rise of Neoclassicism), the 20th and 21st centuries have seen renewed interest in Baroque still life and a greater appreciation for the contributions of female artists.

Today, Margherita Caffi's paintings are held in numerous public and private collections across Italy and internationally. Museums such as the Uffizi Gallery, the Pinacoteca di Brera, the Museo Poldi Pezzoli, and various regional galleries proudly display her work. Her paintings also appear regularly on the art market, where they command significant prices, reflecting continued admiration for her skill and distinctive style. The estimate of €3,000-€5,000 for a Natura morta at auction, as mentioned in earlier sources, indicates the ongoing collector interest.

Her legacy resides not only in the visual appeal of her canvases but also in her story as a successful female professional in a male-dominated era. She navigated the challenges of her time to create a body of work that remains captivating for its technical brilliance, its vibrant aesthetic, and its joyful celebration of the natural world. Margherita Caffi demonstrated that still-life painting could be a vehicle for profound artistic expression, full of life, movement, and dazzling colour.

Conclusion

Margherita Caffi remains a compelling figure in Italian art history. As a master of the Baroque still life, she developed a highly personal style characterized by dynamic compositions, rich colours, and energetic brushwork. Emerging from an artistic family and achieving significant patronage and recognition, she stands as a testament to the talent and perseverance of female artists in the 17th and early 18th centuries. Her vibrant depictions of flowers and fruit continue to engage viewers today, offering a window into the opulent tastes of the Baroque era while showcasing an artistic vision that was uniquely her own. Her contribution to the Lombard school of painting and to the genre of still life ensures her enduring importance.