Theodoor Rombouts (1597-1637) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of Flemish Baroque art. Born in Antwerp, the artistic crucible of Northern Europe, Rombouts carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming one ofthe leading proponents of Caravaggism in the Southern Netherlands. His relatively short but impactful career saw him absorb the revolutionary techniques of Italian masters and reinterpret them through a uniquely Flemish lens, leaving behind a legacy of powerful genre scenes, compelling religious narratives, and striking allegories. Though his fame was later eclipsed by contemporaries like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized Rombouts's artistic merits and his crucial role in the dissemination of Caravaggesque naturalism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Theodoor Rombouts was baptized in Antwerp on July 2, 1597. His artistic journey began under the tutelage of Abraham Janssens (c. 1575–1632) around 1608. Janssens was a prominent figure in Antwerp's art scene, known for his robust, classicizing style and considered by some a rival to the burgeoning talent of Peter Paul Rubens. Janssens himself had spent time in Italy, absorbing influences from both classical antiquity and contemporary Italian painters, including Caravaggio, albeit in a more tempered manner.

Under Janssens, Rombouts would have received a thorough grounding in figure drawing, composition, and the traditional themes of history painting. Janssens's own work, characterized by strong sculptural figures and a clear, often cool, palette, provided a solid foundation for Rombouts. However, the artistic currents of the time were shifting dramatically, largely due to the seismic impact of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio in Rome. It was this more radical, naturalistic, and dramatically lit style that would ultimately captivate the young Rombouts.

The Italian Sojourn: Embracing Caravaggism

Around 1616, following a path trodden by many ambitious Northern European artists, Rombouts traveled to Italy. This period, lasting until 1625, was transformative. He is documented in Rome, the epicenter of the Caravaggesque movement. Here, he encountered firsthand the works of Caravaggio (1571-1610), whose revolutionary use of chiaroscuro (dramatic contrasts of light and dark), unidealized figures drawn from life, and intense psychological realism had sent shockwaves through the art world.

While Caravaggio himself had died a few years prior to Rombouts's likely arrival in Rome, his influence was pervasive, kept alive by a diverse group of followers known as the Caravaggisti. Rombouts became closely associated with this circle. He was particularly influenced by Bartolomeo Manfredi (c. 1582–1622), an Italian painter who popularized what became known as the "Manfrediana methodus." This involved depicting low-life genre scenes – card players, fortune tellers, drinkers, and musicians in taverns – often in a horizontal format, with half-length figures brought close to the picture plane, illuminated by a strong, raking light from an unseen source.

During his Italian years, Rombouts absorbed these stylistic traits. He likely associated with other Northern artists in Rome, such as the Dutch "Bentvueghels" and fellow Flemings like Gerard Seghers (1591–1651) and the French painter Valentin de Boulogne (1591–1632), both of whom were also key figures in Roman Caravaggism. There is also evidence suggesting Rombouts spent time in Florence, possibly working for Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. His Italian output consisted mainly of these popular genre scenes, which found a ready market.

Return to Antwerp: A Leading Caravaggist

Rombouts returned to Antwerp in 1625, a master of the Caravaggesque style. He was admitted as a master to the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in the same year. His return coincided with a period when Caravaggism was gaining traction in Flanders, partly through artists like Rubens, who had also been profoundly influenced by Caravaggio during his own Italian stay, and Louis Finson (1580-1617), who had known Caravaggio personally. However, Rombouts, along with contemporaries like Gerard Seghers and Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678) in his earlier phase, became one of its most dedicated and recognizable practitioners in the city.

His powerful, naturalistic style, with its dramatic lighting and vivid depiction of everyday life, offered a compelling alternative to the more idealized and dynamic High Baroque style championed by Rubens. Rombouts quickly established a successful career. He married Anna van Thielen, the sister of the flower painter Jan Philips van Thielen, in 1627, and the couple had two children. His reputation grew, and he received important commissions, including for religious works. He served as dean of the Guild of Saint Luke from 1628 to 1630, a testament to his standing in the Antwerp artistic community.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Rombouts's mature style is a distinctive fusion of his Italian experiences and his Flemish heritage. The core of his art lies in his commitment to Caravaggesque principles:

Chiaroscuro and Dramatic Lighting: Like Caravaggio and Manfredi, Rombouts employed strong contrasts between light and shadow to model his figures, create a sense of volume, and heighten the drama of his scenes. Light often enters from a single, unseen source, illuminating key figures and details while plunging other areas into deep shadow. This technique, known as tenebrism, lends his paintings an immediate, theatrical impact.

Naturalism and Realism: Rombouts typically depicted figures with a striking sense of realism, avoiding idealization. His characters, whether saints, musicians, or cardsharps, often have a rugged, earthy quality. He paid close attention to the textures of fabrics, the gleam of metal, and the specific features of his models, lending his scenes an air of authenticity.

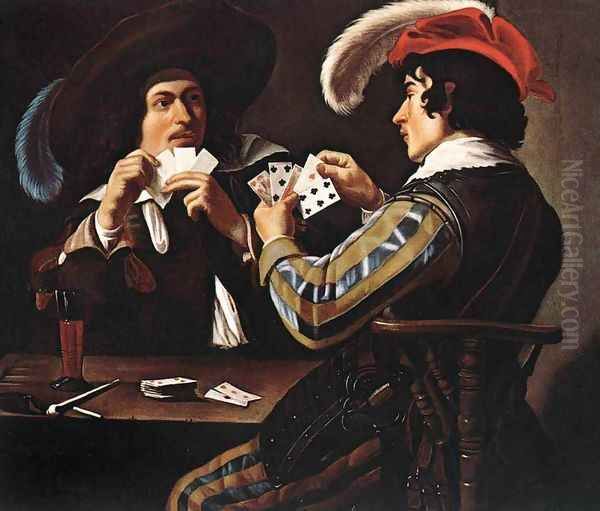

Genre Scenes: A significant portion of Rombouts's oeuvre consists of genre scenes, particularly those depicting musicians, card players, and merry companies. These works, often large-scale and featuring half-length or three-quarter-length figures, are characterized by their lively interactions, expressive gestures, and sometimes, a moralizing undertone, warning against the vices of gambling or excessive drinking. Works like The Card Players or The Lute Player exemplify this aspect of his work.

Religious and Allegorical Subjects: While renowned for his genre scenes, Rombouts also produced powerful religious paintings. Works such as The Descent from the Cross (St. Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent) demonstrate his ability to apply Caravaggesque drama and realism to sacred narratives, imbuing them with emotional intensity. He also painted allegorical subjects, such as The Allegory of the Five Senses, where his skill in rendering diverse figures and objects is evident.

Composition and Color: Rombouts often favored horizontal compositions, especially for his multi-figure genre scenes, a hallmark of the Manfrediana methodus. His figures are typically arranged in a relatively shallow space, close to the viewer. While his palette could be somewhat more subdued than that of Rubens, it was often richer and more varied than that of some of the more austere Caravaggisti, incorporating vibrant reds, blues, and yellows that reflect his Flemish training. His brushwork is generally precise, capturing detail effectively.

Compared to Rubens, Rombouts's art is less overtly dynamic and heroic, focusing more on intimate, psychologically charged moments. While Rubens embraced a more classical and idealized vision, Rombouts remained closer to the raw naturalism of Caravaggio. He shares some affinities with the Utrecht Caravaggisti in the Dutch Republic, such as Hendrick ter Brugghen (1588–1629) and Dirck van Baburen (c. 1595–1624), who also brought Caravaggesque innovations north.

Key Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as representative of Rombouts's artistic achievement:

The Card Players (various versions, e.g., National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen): This theme was a staple for Rombouts and other Caravaggisti. These paintings typically depict a group of figures, often soldiers or dandies, engrossed in a game of cards. The atmosphere is often tense, with opportunities for depicting cunning expressions, cheating, and the allure of easy money. Rombouts excels in capturing the varied characters and the psychological interplay between them, all highlighted by dramatic lighting.

The Lute Player (e.g., Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Philadelphia Museum of Art): Musical themes were also popular. The Lute Player often features a single musician, or a small group, engaged in performance. These works allowed Rombouts to showcase his skill in rendering instruments, costumes, and expressive faces, often imbued with a melancholic or romantic air. The depiction of musicians was a common trope in Caravaggesque painting, seen in works by Caravaggio himself, as well as followers like Orazio Gentileschi (1563–1639) and his daughter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – c. 1656).

The Allegory of the Five Senses (c. 1632, Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent): This large and ambitious work, commissioned by the Bishop of Ghent, Antoon Triest, is a complex allegorical scene. It depicts figures representing Sight, Hearing, Smell, Taste, and Touch, surrounded by objects associated with each sense. The painting showcases Rombouts's mastery of composition, his ability to handle a multi-figure scene with clarity, and his skill in rendering diverse textures and still-life elements. It also demonstrates his capacity to tackle more intellectually demanding subjects beyond straightforward genre scenes.

Descent from the Cross (St. Bavo's Cathedral, Ghent): This significant religious commission reveals Rombouts's ability to convey profound emotion and spiritual weight. The dramatic lighting inherent in his Caravaggesque style is perfectly suited to the solemnity and tragedy of the subject. The figures are rendered with a tangible physicality and grief, making the sacred event immediate and relatable to the viewer. This work invites comparison with other Baroque interpretations of the theme, such as those by Rubens or Van Dyck, highlighting Rombouts's distinct, more naturalistic approach.

Musical Company with Bacchus (Philadelphia Museum of Art): This painting combines the popular theme of a musical gathering with a mythological element, featuring Bacchus, the god of wine. It's a lively scene, characteristic of the "merry company" genre, filled with animated figures, music-making, and drinking. Such works often carried moralizing messages about temperance or the fleeting nature of pleasure, though they were also appreciated for their vibrant depiction of social life.

Prometheus (Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels): Tackling a powerful mythological subject, this work likely depicts Prometheus chained, with the eagle tormenting him. The Caravaggesque style, with its strong contrasts and focus on dramatic moments, would be highly effective in conveying the suffering and intensity of this myth.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

In the collaborative artistic environment of 17th-century Antwerp, it was common for painters to specialize and work together. While Rombouts was primarily a figure painter, he did engage in some collaborations. There is evidence suggesting he may have painted figures in still lifes by Adriaen van Utrecht (1599–1652), a prominent still-life specialist.

His relationship with Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) is noteworthy. While Rombouts's teacher, Janssens, was a rival to Rubens, Rombouts himself seems to have maintained a professional, if stylistically distinct, presence. There is a record of Rombouts collaborating with Rubens on a painting depicting the Temple of Janus for the Joyous Entry of Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand into Antwerp in 1635, though Rubens was the overarching designer of such large-scale decorative projects.

Gerard Seghers was another important contemporary with whom Rombouts shared a strong affinity for Caravaggism, particularly after their respective returns from Italy. Jacob Jordaens, in his earlier works, also showed a clear Caravaggesque influence before developing his more robust, Rubenesque style. Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), a brilliant pupil of Rubens, pursued a more elegant and courtly Baroque style, which, along with Rubens's overwhelming dominance, contributed to the relative overshadowing of artists like Rombouts in later art historical narratives.

Rombouts also had pupils, though they are not as extensively documented as those of Rubens or Jordaens. One notable student was likely Nicolaes van Eyck (1617-1679), and possibly Adam de Coster (c. 1586–1643), another Flemish Caravaggist known for his candlelit scenes, though the master-pupil relationship with De Coster is less certain.

Legacy and Historical Reception

Theodoor Rombouts enjoyed considerable success during his lifetime. His paintings were sought after by patrons and collectors, and he held a respected position within the Antwerp artistic community. His robust Caravaggesque style offered a distinct and powerful vision that resonated with contemporary tastes for naturalism and drama.

However, after his premature death in 1637 at the age of forty, his reputation gradually faded. The overwhelming artistic legacy of Rubens and Van Dyck came to define the image of Flemish Baroque art for centuries, and the contributions of other talented masters like Rombouts were often marginalized. The more classical and idealized High Baroque style, with its dynamism and grandeur, largely superseded the more austere and naturalistic Caravaggism in Flanders by the mid-17th century.

It was not until the 20th century, with a renewed scholarly interest in Caravaggio and the international Caravaggesque movement, that artists like Rombouts began to receive greater attention. Art historians started to re-evaluate his work, recognizing his skill, his importance as a conduit for Italian artistic ideas in the North, and the intrinsic quality of his paintings. Exhibitions, such as the one dedicated to him at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent in 2023, have played a crucial role in bringing his art to a wider public and solidifying his place in the history of Flemish art.

Today, Rombouts is acknowledged as one of the foremost Flemish Caravaggisti. His ability to synthesize the dramatic intensity of Italian Caravaggism with a Flemish sensibility for color and detailed observation resulted in a body of work that is both powerful and engaging. His paintings offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic currents of his time and provide a valuable counterpoint to the more dominant Rubenesque tradition.

Where to See His Works

Paintings by Theodoor Rombouts are held in numerous prestigious museums and collections around the world. Key institutions include:

Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent (MSK Gent), Belgium: Holds several important works, including The Allegory of the Five Senses and The Descent from the Cross (on loan to St. Bavo's Cathedral).

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels: Features works like Prometheus.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA: Home to a version of The Lute Player.

National Gallery of Denmark (SMK), Copenhagen: Possesses Card and Backgammon Players. Fight.

Philadelphia Museum of Art, USA: Collections include Musical Company with Bacchus and another Lute Player.

Alte Pinakothek, Munich, Germany.

Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Various other public and private collections across Europe and North America also house his works.

Conclusion: A Rediscovered Master

Theodoor Rombouts was an artist of considerable talent and significance whose career, though brief, made a lasting impact on Flemish art. As a leading proponent of Caravaggism in Antwerp, he skillfully adapted the revolutionary techniques of light and shadow, naturalism, and psychological intensity pioneered in Italy to his own cultural context. His depictions of lively genre scenes, compelling religious narratives, and thoughtful allegories showcase his mastery of composition, his keen observational skills, and his ability to imbue his subjects with a palpable sense of presence.

While for a time overshadowed by the towering figures of Rubens and Van Dyck, Rombouts's artistic contributions are now increasingly appreciated. He stands as a vital link in the international network of Caravaggesque painters and as a testament to the diversity and richness of the Flemish Baroque. His works continue to engage viewers with their dramatic power, their vivid portrayal of human life, and their enduring artistic quality, securing his place as a rediscovered master of the 17th century.