Bartolomeo Manfredi, an artist whose name is inextricably linked with the revolutionary art of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, stands as a pivotal figure in the development of early Baroque painting in Rome. Though his own fame was somewhat eclipsed by the very master he emulated, Manfredi was instrumental in codifying and disseminating Caravaggio's dramatic naturalism and use of chiaroscuro, creating a distinct thematic repertoire that profoundly influenced a generation of artists across Europe. His approach, later dubbed the "Manfrediana Methodus," became a hallmark for many painters drawn to the vibrant artistic crucible of Rome in the early 17th century.

Early Life and Arrival in Rome

Born in Ostiano, a small town near Mantua, in August 1582, Bartolomeo Manfredi's early life and artistic training remain somewhat obscure. It is generally accepted that he arrived in Rome sometime before 1603, placing him in the city during the height of Caravaggio's fame and notoriety. The Lombard origins of both artists might have facilitated an initial connection, as Rome was a magnet for artists from all over Italy and beyond, often forming regional communities.

The exact nature of Manfredi's initial training is not definitively documented. While some scholars suggest he may have had contact with artists from the Cremonese or Mantuan schools before his arrival in Rome, it was the encounter with Caravaggio's work, and possibly the master himself, that would prove decisive for his artistic trajectory. By 1610, official records confirm his residence in Rome, specifically in the parish of Sant'Andrea delle Fratte, an area popular with artists.

The Shadow and Light of Caravaggio

Manfredi is considered one of Caravaggio's closest and most important followers. The impact of Caravaggio's radical naturalism, his dramatic use of tenebrism (the stark contrast of light and shadow), and his preference for depicting figures drawn from life, often common people, resonated deeply with Manfredi. It is highly probable, though not definitively proven with contemporary documents, that Manfredi spent some time in Caravaggio's workshop or, at the very least, had ample opportunity to study his works closely.

Caravaggio's departure from Rome in 1606, following a fatal brawl, left a vacuum that many artists, including Manfredi, sought to fill. Manfredi did not merely copy Caravaggio's style; rather, he absorbed its fundamental principles and adapted them to his own artistic sensibilities and, crucially, to the demands of the art market. He became particularly adept at capturing the intense psychological drama and palpable realism that were hallmarks of Caravaggio's revolutionary approach.

His skill in emulating Caravaggio's style was such that, for centuries, many of Manfredi's own works were misattributed to Caravaggio himself. This confusion, while complicating art historical scholarship, speaks volumes about Manfredi's mastery of the Caravaggesque idiom. He understood the power of focused light to model form, create atmosphere, and direct the viewer's attention, often setting his scenes in dimly lit interiors where figures emerge dramatically from the shadows.

The "Manfrediana Methodus"

The term "Manfrediana Methodus" (Manfredian Method) was coined by the 17th-century German painter and art historian Joachim von Sandrart. Sandrart, who was in Rome in the late 1620s and early 1630s, used this term to describe the particular thematic and stylistic approach popularized by Manfredi and adopted by many subsequent Caravaggisti. It wasn't just about the use of chiaroscuro, but also about the choice of subject matter.

Manfredi specialized in genre scenes, often depicting what were considered low-life subjects: raucous gatherings in taverns, soldiers in guardrooms engaged in gambling or drinking, concerts with musicians, and fortune-telling scenes. While Caravaggio had painted some such subjects earlier in his career (e.g., "The Cardsharps," "The Fortune Teller"), Manfredi made them his signature. He typically employed half-length or three-quarter-length figures, brought close to the picture plane, creating an immediate and often confrontational engagement with the viewer.

His compositions were generally simpler than Caravaggio's later, more complex religious narratives, focusing on a small group of figures interacting within a confined space. The light, while dramatically employed, could sometimes be brighter and the handling of paint slightly softer or more blended than Caravaggio's often starker contrasts and more direct application. Manfredi's figures, though naturalistic, often possessed a certain idealized robustness. He excelled in depicting varied human emotions and interactions, making his narrative scenes compelling and legible.

Key Themes and Subjects

Manfredi's oeuvre is dominated by these characteristic genre scenes. Paintings of soldiers carousing, playing cards, or dicing were particularly popular. These works often captured a sense of camaraderie, tension, and the fleeting pleasures of life. Examples include "The Guardroom" or "Soldiers Playing Dice," which showcase his ability to render varied textures, from gleaming armor to rough-spun fabrics, and to capture expressive gestures and glances.

Musical parties, or "concerts," were another favorite theme. These paintings typically depict a group of musicians, often in contemporary attire, playing various instruments. Works like "The Concert" (versions of which exist, one notably in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence) highlight his skill in portraying the absorption of the musicians in their performance and the interplay between them. These scenes often carried allegorical meanings related to harmony, love, or the transience of worldly pleasures.

Fortune-telling scenes, continuing a theme initiated by Caravaggio, also feature in Manfredi's work. "The Fortune Teller" (one version in the Detroit Institute of Arts) shows a young man having his palm read by a gypsy woman, a subject that allowed for the depiction of subtle psychological interplay and often carried a moralizing undertone about gullibility and deception.

While best known for these secular genre scenes, Manfredi also painted religious subjects. These, too, were executed in a strong Caravaggesque style, emphasizing the humanity of the sacred figures and the dramatic intensity of the moment. Works such as "The Denial of St. Peter" (Museo Diocesano, Urbino) or "Christ Crowned with Thorns" demonstrate his ability to apply his dramatic lighting and naturalistic figures to devotional themes, often focusing on moments of intense human suffering or spiritual crisis. "The Capture of Christ" (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) is another powerful example, conveying the chaos and betrayal of the event with stark realism.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as quintessential examples of Manfredi's art and the "Manfrediana Methodus."

"Cupid Chastised" (Art Institute of Chicago): This dynamic and somewhat enigmatic painting, likely executed around 1613, depicts Mars, the god of war, vigorously whipping a cowering Cupid, while Venus attempts to intervene. The scene is rendered with Manfredi's characteristic strong chiaroscuro, with the figures emerging powerfully from a dark background. The muscular anatomy of Mars and the expressive poses of the figures are typical of his style. The subject itself, with its undertones of eroticism and power dynamics, was popular in the period and allowed for a display of dramatic action and emotion. Some interpretations also suggest a Neoplatonic allegory about the subjugation of earthly love by higher principles.

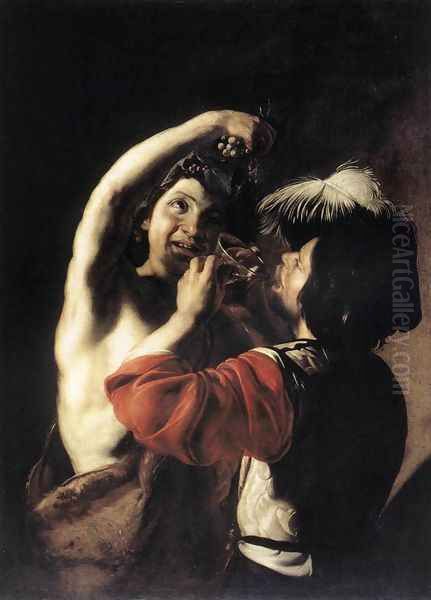

"Bacchus and a Drinker" (Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome): This work, sometimes titled "Allegory of the Four Seasons" or simply "Drinking Scene," shows a youthful Bacchus, crowned with grapevines, offering wine to an eager drinker. Other figures, potentially representing seasons or different ages of man, surround them. The painting is a vibrant example of Manfredi's tavern scenes, filled with lively figures, rich colors, and a palpable sense of revelry. The naturalistic depiction of the figures and the skillful rendering of still-life elements like fruit and wine vessels are noteworthy.

"The Triumph of David" (Musée du Louvre, Paris): This painting depicts the young David with the head of Goliath. Unlike many heroic representations, Manfredi focuses on a more contemplative moment, with David and surrounding figures rendered with a somber realism. The dramatic lighting highlights David's youthful form and the gruesome trophy, creating a powerful visual and psychological impact. This work shows his ability to imbue traditional biblical scenes with the immediacy of his genre paintings.

"Allegory of the Four Seasons" (Dayton Art Institute, Ohio): This composition features figures personifying Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter, often engaged in activities or holding attributes associated with each season. Manfredi's version is notable for its robust, earthy figures and the rich, warm palette. It showcases his skill in group compositions and his ability to convey allegorical content through naturalistic representation.

"The Concert" (Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence): This is one of Manfredi's most famous concert scenes. It depicts a group of musicians, some singing, others playing instruments like the lute and violin. The figures are closely grouped, their expressions intent as they engage in their music-making. The interplay of light and shadow models their forms and creates an intimate atmosphere. Such scenes were highly sought after by collectors and reflect the period's interest in music and its social role.

Influence and Legacy

Bartolomeo Manfredi's primary importance lies in his role as a conduit for Caravaggism. While Caravaggio himself had few direct pupils in the traditional sense, Manfredi, through his consistent production of works in the master's style but with a more accessible thematic range, effectively created a "school" or a defined approach that other artists could follow. His paintings were highly sought after by collectors, both Italian and foreign, which helped to spread this style.

His influence was particularly strong on Northern European artists who came to Rome. The so-called Utrecht Caravaggisti, including Dutch painters like Hendrick ter Brugghen, Gerard van Honthorst, and Dirck van Baburen, were profoundly affected by Manfredi's work. Upon their return to the Netherlands, they popularized similar genre scenes – merry companies, musicians, drinkers – adapting the Caravaggesque style to their own cultural context. Van Honthorst, known as "Gherardo delle Notti" for his candlelit scenes, especially shows a debt to the thematic and compositional choices popularized by Manfredi.

French artists active in Rome were also significantly influenced. Valentin de Boulogne is perhaps the most prominent French Caravaggist whose work runs parallel to Manfredi's, often exploring similar themes of tavern scenes, concerts, and soldiers with a comparable dramatic intensity and psychological depth. Indeed, the works of Manfredi and Valentin are sometimes difficult to distinguish. Other French artists like Nicolas Tournier and Nicolas Régnier (who was, according to some sources, a student of Manfredi) also adopted the "Manfrediana Methodus." Régnier, in particular, after his time in Rome, continued to work in a style that blended Caravaggesque realism with a more elegant, refined sensibility.

Even in Italy, artists like Cecco del Caravaggio (whose identity is still debated but was a close follower of Caravaggio), Orazio Gentileschi and his daughter Artemisia Gentileschi, while developing their own distinct styles, operated within the broader Caravaggesque movement that Manfredi helped to define and sustain. While Orazio Gentileschi leaned towards a more lyrical and refined Caravaggism, Artemisia embraced its dramatic potential with powerful female heroines. The Neapolitan painter Jusepe de Ribera ("Lo Spagnoletto"), though Spanish by birth, spent much of his formative period in Italy and his early work shows a strong affinity with the tenebrism and gritty realism championed by Caravaggio and disseminated by artists like Manfredi. Even the early works of Spanish masters like Francisco de Zurbarán show an understanding of tenebrism that likely filtered through such channels.

The influence of Manfredi's popularization of genre scenes extended beyond direct stylistic imitation. He helped to elevate these everyday subjects to a level of artistic seriousness previously reserved for historical or religious painting, paving the way for the flourishing of genre painting in 17th-century Europe. Artists like Giovanni Baglione, a contemporary and rival of Caravaggio, and later a biographer, acknowledged the impact of this new style, even if critically. The more classicizing trend in Roman Baroque art, represented by figures like Annibale Carracci, offered a contrasting artistic vision, but the power of Caravaggism, as channeled by Manfredi, was undeniable. The German painter Adam Elsheimer, also active in Rome, though working on a smaller scale, shared an interest in innovative light effects that paralleled some Caravaggesque concerns. Even the great Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, who was in Italy during Caravaggio's and Manfredi's time, absorbed elements of Caravaggio's drama and lighting into his own exuberant Baroque style.

Personal Life and Character: Anecdotes and Controversies

Like many artists of the period, particularly those associated with the often-turbulent Caravaggio, Manfredi's life was not without its share of drama. While detailed biographical information is scarce, surviving court records and contemporary accounts paint a picture of a man who, like his mentor, could be impetuous and involved in altercations.

There are records of Manfredi being arrested for illegally carrying weapons, a common offense in the often-dangerous streets of Rome but one that nonetheless points to a certain temperament. He was also reportedly involved in violent incidents. One anecdote, though its veracity is debated, suggests he was involved in an attack on creditors. Financial difficulties and entanglements, including a relationship with a mistress that caused him trouble, seem to have been part of his life.

These glimpses into his personal life, while fragmentary, suggest a character that perhaps resonated with the raw, unvarnished realism of his paintings. He lived and worked in a Rome that was a city of stark contrasts – of piety and vice, artistic brilliance and street violence – and his art often reflected this grittier side of life.

Attribution Challenges and Artistic Identity

A significant challenge in studying Manfredi is the issue of attribution. He rarely signed his works. Combined with his exceptional skill in emulating Caravaggio's style, and the fact that many other artists adopted the "Manfrediana Methodus," it has led to considerable confusion in assigning authorship to many paintings from this period. It is estimated that only around 40 works can be securely attributed to him today.

For many years, art collections and museums often labeled works by Manfredi, Valentin de Boulogne, or other Caravaggisti simply as "Caravaggio" or "School of Caravaggio." Modern scholarship, through careful stylistic analysis and documentary research, has gradually worked to disentangle these artistic personalities. The very existence of the "Manfrediana Methodus" as a recognizable category, however, underscores his role in creating a distinct artistic current, even if individual works within it are sometimes debated. This difficulty in attribution ironically highlights his success in capturing and popularizing the Caravaggesque aesthetic.

Later Years and Death

Bartolomeo Manfredi's career was relatively short. He died in Rome on December 12, 1622, at the age of forty. The cause of his death is not recorded, but his passing at a relatively young age cut short the career of an artist who had become a central figure in the Roman art scene. Despite his relatively brief period of activity, his impact was substantial and lasting.

His death occurred at a time when Caravaggism was still a potent force, but new trends were also emerging. However, the seeds he had sown, particularly in popularizing specific types of genre scenes, would continue to bear fruit in the work of his many followers and admirers across Europe.

Conclusion: An Enduring Legacy

Bartolomeo Manfredi, though perhaps not possessing the revolutionary genius of Caravaggio, was far more than a mere imitator. He was a highly skilled and intelligent artist who understood the core principles of Caravaggio's art and adapted them into a marketable and influential "method." He played a crucial role in popularizing Caravaggesque naturalism and tenebrism, particularly through his focus on engaging genre scenes that captured the imagination of patrons and fellow artists alike.

His "Manfrediana Methodus" provided a template for a generation of painters, especially those from Northern Europe, who flocked to Rome to absorb the latest artistic innovations. Through them, Manfredi's influence spread far beyond Italy, contributing significantly to the international development of Baroque painting. While often overshadowed by the colossal figure of Caravaggio, Bartolomeo Manfredi remains a key artist for understanding the dissemination and evolution of one of the most powerful and enduring styles in Western art history. His ability to capture the drama of everyday life, illuminated by stark and revealing light, ensures his place as a significant master of the early Baroque period.