Lilla Cabot Perry stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the narrative of American art, particularly as a pioneering female artist and a crucial conduit for Impressionist ideals from France to the United States. Her life, spanning a dynamic period of artistic revolution and societal change, was marked by a relentless pursuit of artistic expression, a deep engagement with diverse cultures, and a commitment to fostering an appreciation for modern art in her homeland. Born into privilege, she leveraged her position not for leisure alone, but to carve out a distinguished career as a painter, poet, and an influential advocate for the Impressionist movement.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Lydia (Lilla) Cabot was born on January 13, 1848, in Boston, Massachusetts, into one of the city's most distinguished and socially prominent families, often referred to as Boston Brahmins. Her father, Dr. Samuel Cabot III, was an eminent surgeon, and her mother, Hannah Lowell Jackson Cabot, hailed from the equally esteemed Lowell family. This lineage provided Lilla with an upbringing steeped in culture, intellectual discourse, and connections to leading figures of the era, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, a family friend. Her early education was typical for a young woman of her station, emphasizing literature, languages, and the arts, though formal art training would come later.

The American Civil War cast a shadow over her youth, with her parents being ardent abolitionists and actively involved in the Union cause. These formative years likely instilled in her a sense of purpose and a broad worldview. In 1874, Lilla Cabot married Thomas Sergeant Perry, a scholar and professor of English literature at Harvard University, and a grandnephew of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who famously opened Japan to the West. Their union was one of intellectual companionship, and Thomas was consistently supportive of Lilla's artistic ambitions. The couple had three daughters: Margaret (born 1876), Edith (born 1880), and Alice (born 1884), who would frequently feature as subjects in her paintings.

The Awakening of an Artist

It wasn't until Lilla Cabot Perry was in her mid-thirties, around 1884, that she began to pursue art seriously. This relatively late start was not uncommon for women of her time, who often prioritized familial duties before dedicating themselves to professional pursuits. Her initial artistic explorations included sketching her children and taking private lessons. Her formal training commenced in Boston, where she studied portraiture under Alfred Quentin Collins. She also attended classes taught by Robert Vose and Dennis Miller Bunker at the Cowles Art School. Bunker, who had himself studied in Paris and absorbed Impressionist tendencies, likely provided Perry with her first significant exposure to the burgeoning modern art movement.

The Perrys' decision to move to Paris in 1887 marked a pivotal turning point in Lilla's artistic development. Paris was then the undisputed center of the art world, and Perry immersed herself in its vibrant atmosphere. She enrolled at the Académie Colarossi, one of the few Parisian art schools that admitted women, where she studied under Gustave Courtois and Joseph Blanc. She also sought instruction at the Académie Julian with Tony Robert-Fleury. However, perhaps her most influential early European teacher was Alfred Stevens, a Belgian painter known for his elegant depictions of contemporary women and his sophisticated use of color. Stevens encouraged her to observe and capture the nuances of modern life.

During these early years in Paris, Perry's work, while technically proficient, still largely adhered to the academic traditions she was being taught. She exhibited at the Paris Salon, a significant achievement for any artist, particularly an American woman. Her painting La Petite Angèle, II (1888) was accepted, signaling her growing competence and ambition.

The Impressionist Revelation: Monet and Giverny

The year 1889 was transformative for Lilla Cabot Perry. It was then, at Georges Petit's gallery in Paris, that she first encountered the work of Claude Monet. She was profoundly moved by his paintings, later recalling, "I was so impressed by his work that I made up my mind that I would go to see him and try to work near him." This encounter ignited her passion for Impressionism, a style that emphasized capturing the fleeting effects of light and color, often painted en plein air (outdoors).

True to her resolve, Perry and her family began spending summers in Giverny, the small French village where Monet had established his home and iconic gardens. From 1889 to 1909, with some interruptions, the Perrys were regular fixtures in Giverny, becoming close neighbors and friends with Monet. This proximity allowed Perry unparalleled access to the master Impressionist. While Monet did not take on formal students, he offered Perry critiques and encouragement, profoundly shaping her artistic vision. She absorbed his techniques: the broken brushwork, the vibrant palette, the focus on atmospheric conditions, and the practice of painting series to capture changing light.

Perry's Giverny paintings from this period, such as Haystacks, Giverny (c. 1890s) and numerous landscapes featuring the local scenery, clearly demonstrate Monet's influence. She adopted his method of observing a subject at different times of day and under various weather conditions. Her friendship with Monet was a cornerstone of her artistic life, and she, in turn, became one of his most ardent American champions. Other American artists also congregated in Giverny, forming an expatriate colony, including Theodore Robinson, Willard Metcalf, and Theodore Earl Butler, creating a stimulating environment for artistic exchange.

The Japanese Interlude and Its Impact

A significant chapter in Perry's artistic journey was her time in Japan. Her husband, Thomas Sergeant Perry, accepted a teaching position in Tokyo, and the family lived there from 1898 to 1901. This experience had a profound and lasting impact on Lilla Cabot Perry's art. She immersed herself in Japanese culture and art, particularly Ukiyo-e woodblock prints by masters like Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige.

The influence of Japanese art, or Japonisme, was already a significant trend among Impressionists like Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, and Monet himself. For Perry, however, direct exposure to Japan deepened this connection. She admired the asymmetrical compositions, the flattened perspectives, the bold use of line, the decorative patterns, and the subtle color harmonies characteristic of Japanese prints. She began to incorporate these elements into her own work, creating a distinctive fusion of Western Impressionism and Eastern aesthetics.

Her Japanese-period paintings often feature Japanese subjects, landscapes like Mount Fuji, and domestic scenes, rendered with an Impressionist sensibility but informed by Japanese compositional principles. Works like The Trio (Alice, Edith, and Margaret Perry) (c. 1900) and Lady with a Bowl of Violets (c. 1910, painted after her return but showing lasting influence) exhibit this synthesis. She also experimented with Japanese painting techniques and materials. Her time in Japan not only enriched her artistic vocabulary but also broadened her understanding of global art traditions.

Themes, Style, and Representative Works

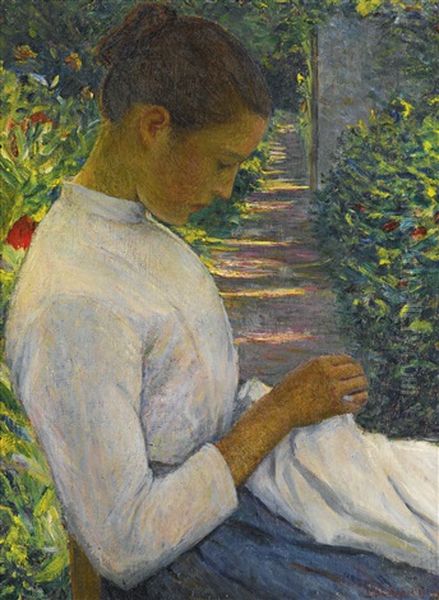

Lilla Cabot Perry's oeuvre is characterized by several recurring themes and a distinctive stylistic evolution. Portraits, particularly of women and children, form a significant portion of her work. Her daughters were frequent models, and these paintings often convey a sense of intimacy and maternal affection. Works like Edith Perry with a Dog (The Green Hat) (c. 1890) and Child in a Window (1896) showcase her ability to capture the innocence and individuality of her subjects, bathed in the soft, diffused light characteristic of Impressionism.

Landscapes were another major focus, especially during her Giverny years and her time in Japan. She was adept at capturing the atmospheric qualities of different environments, from the sun-drenched fields of Normandy to the misty vistas of Japan. Her landscapes often feature a high horizon line and a focus on the interplay of light and shadow, reflecting Monet's influence.

Her artistic style is firmly rooted in Impressionism. She employed a bright palette, often using pure, unmixed colors applied with visible, broken brushstrokes to convey the sensation of light and movement. While clearly influenced by Monet, Perry developed her own nuanced approach. Her brushwork could be both delicate and vigorous, and her compositions often balanced Impressionist spontaneity with a more traditional concern for structure, perhaps a lingering effect of her academic training or her New England sensibilities.

Some of her most representative works include:

La Petite Angèle, II (1888): An early Salon piece showing her academic skill before her full embrace of Impressionism.

Open Air Concert (c. 1890): Depicts figures in a sun-dappled outdoor setting, showcasing her early adoption of Impressionist light effects.

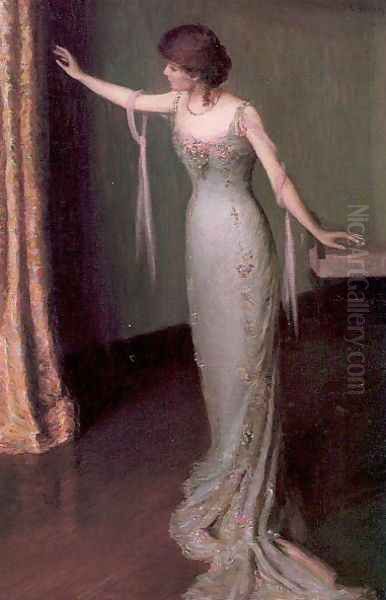

Portrait of Mrs. Joseph C. Grew (Alice Perry Grew) (c. 1907): A mature portrait demonstrating her skill in capturing likeness and character with Impressionist flair.

Lady with a Bowl of Violets (c. 1910): A celebrated work that beautifully melds Impressionist technique with a subtle Japonisme in its composition and delicate sensibility.

Easter Morning (1915): A vibrant depiction of her daughter, Margaret, exemplifying her mature Impressionist style, with a focus on light, color, and intimate domesticity.

Young Caretaker (1899): Likely painted during or reflecting her Japanese period, showcasing her interest in everyday scenes and character.

Girl Playing a Cello (1891): An interior scene that demonstrates her handling of light and her ability to capture a moment of quiet concentration.

The White Bed Jacket (c. 1905): A tender portrayal, likely of one of her daughters, showcasing her mastery of whites and subtle color variations.

Her work often explored the world of women and children, a common focus for female artists of the period, including Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. However, Perry's depictions are infused with her unique blend of American pragmatism and European sophistication.

Champion of Impressionism in America

Upon her returns to Boston from Europe and Japan, Lilla Cabot Perry became a fervent advocate for Impressionism in the United States. At a time when the style was still met with skepticism by conservative American critics and audiences, Perry worked tirelessly to promote it. She delivered lectures on Monet and other Impressionists, sharing her firsthand experiences and insights. She encouraged wealthy American collectors, including her Cabot relatives, to purchase Impressionist works, thereby helping to build some of the foundational collections of French Impressionism in American museums.

In 1914, she was a founding member of the Guild of Boston Artists, an artist-run cooperative gallery. This organization provided an important venue for Boston artists, including those working in Impressionist and Post-Impressionist styles, to exhibit and sell their work. Perry's social standing and articulate advocacy lent credibility to the movement. She was part of a wave of American artists, including Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, J. Alden Weir, and Edmund C. Tarbell, who adapted Impressionism to American subjects and sensibilities, forming the core of what became known as American Impressionism. Her close friendship with Mary Cassatt, another prominent American Impressionist based in Paris, further solidified her connections within the movement. She also knew Camille Pissarro and likely encountered other key figures like Edgar Degas through Cassatt.

Later Years and Continued Artistic Production

The Perrys returned permanently to the United States in 1909, settling in Boston but spending summers in Hancock, New Hampshire. Perry continued to paint prolifically throughout her later years, adapting her Impressionist style to the New England landscape. Her Hancock paintings often depict the serene beauty of the region, with its rolling hills, tranquil lakes, and changing seasons. These later works retain her characteristic sensitivity to light and color, though some exhibit a slightly more structured approach to composition.

She remained an active exhibitor, participating in shows in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Despite the rise of new modernist movements like Cubism and Fauvism, Perry remained committed to the Impressionist aesthetic that had defined her career. Her dedication to her craft was unwavering, and she continued to find inspiration in her surroundings and the people she loved.

Beyond her painting, Lilla Cabot Perry was also a published poet. She released four volumes of poetry: The Heart of the Weed (1887), Impressions: A Book of Verse (1898), The Jar of Dreams (1923), and From the Garden of Hellas: Translations from the Greek Anthology (1928). Her poetry, like her painting, often reflects a keen observation of nature and human emotion, imbued with a lyrical sensibility.

Legacy and Reappraisal

Lilla Cabot Perry passed away on February 28, 1933, in Hancock, New Hampshire, at the age of 85. In the decades immediately following her death, her work, like that of many female artists and Impressionists who did not follow the path of radical modernism, faded somewhat from public and critical attention. The art world's focus shifted dramatically towards abstraction and other avant-garde movements.

However, a significant reappraisal of her contributions began in the latter half of the 20th century, fueled by a renewed interest in American Impressionism and a growing recognition of the achievements of women artists. A major retrospective exhibition of her work, organized by the Hirschl & Adler Galleries in New York in 1969, and another at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, played a crucial role in re-establishing her reputation. Scholars began to examine more closely her role as a bridge between French and American Impressionism, her unique synthesis of Western and Eastern aesthetics, and the quality of her artistic output.

Today, Lilla Cabot Perry is recognized as a key figure in American Impressionism. Her paintings are held in the collections of major museums, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.; and the Terra Foundation for American Art. Her life and work offer a compelling example of an artist who successfully navigated the challenges faced by women in the art world of her time, creating a body of work that is both historically significant and aesthetically engaging. Her dedication to capturing the beauty of the world around her, filtered through the luminous lens of Impressionism, ensures her enduring place in the annals of art history. Her close association with Claude Monet, her pioneering spirit in embracing Japanese art, and her tireless promotion of modern art in America underscore her multifaceted importance.