The story of Greek art is rich and varied, stretching from the classical splendors of antiquity through the iconic spiritualism of Byzantium to the complex dialogues of modernity. Within this grand tapestry, the contributions of self-taught, or "naïve," artists offer a unique and invaluable perspective, capturing the soul of a people and their traditions with unvarnished honesty. Among these figures, Theofilos Hadjimichail (Greek: Θεόφιλος Χατζημιχαίλ) stands as a monumental presence, a painter whose vibrant works immortalized the myths, histories, and everyday life of Greece. His journey from an eccentric, often misunderstood figure to a celebrated national icon is a testament to his singular vision and the enduring power of his art.

Early Life and Artistic Germination

Theofilos, whose full name was Theofilos Kefalas-Hadjimichail, was born around 1870 in the village of Vareia, near Mytilene, on the Aegean island of Lesbos, then part of the Ottoman Empire. The exact year of his birth is subject to some debate among scholars, with dates ranging from 1867 to 1873 often cited, but circa 1870 is the most commonly accepted approximation. His father, Gavriil Kefalas, was a shoemaker, and his mother, Pinelopi Hadjimichail (from whom he took his more commonly used surname), was the daughter of an iconographer, Konstantinos Hadjimichail. This maternal lineage likely provided his earliest exposure to artistic creation, planting the seeds of a lifelong passion.

From a young age, Theofilos displayed a keen interest in drawing and painting, though his formal schooling was reportedly unremarkable. He was not an academic child in the traditional sense, but his visual acuity and desire to represent the world around him were undeniable. His grandfather, the icon painter, would have introduced him to the techniques and conventions of Byzantine art, a style characterized by its spiritual intensity, stylized figures, and use of symbolic color. While Theofilos would later develop a distinctly personal and less formal style, the echoes of this early influence can be discerned in the compositional clarity and narrative directness of his mature work. He was largely self-taught, honing his skills through observation, practice, and an unwavering dedication to his craft.

A Nomadic Existence and Unconventional Path

Around the age of eighteen, Theofilos left Lesbos, seeking opportunities beyond his island home. His travels took him to various parts of the Greek world. He spent time in Smyrna (Izmir), a vibrant cosmopolitan port city on the Anatolian coast with a large Greek population. There, he found work in the Greek consulate, reportedly as a gatekeeper or guard (kavasis). This period in Smyrna would have exposed him to a wider array of cultural influences and perhaps further fueled his artistic ambitions, though details of his artistic activities there are scarce.

A defining characteristic of Theofilos's persona was his insistence on wearing the traditional Greek foustanella, a kilt-like garment that was a potent symbol of Greek identity and heroism, particularly associated with the fighters of the Greek War of Independence (1821-1829). In an era when Western European dress was becoming increasingly common in urban centers, Theofilos's attire made him a conspicuous and often eccentric figure. He was frequently the subject of ridicule and mockery, yet he steadfastly clung to this outward expression of his Hellenic pride and perhaps his artistic identity, seeing himself as a custodian of Greek tradition. This attire was not merely a costume but an integral part of his being, reflecting the themes that would dominate his art.

After Smyrna, Theofilos spent several years in Volos, a city in Thessaly on the Greek mainland, around 1897. It was here that his artistic activities became more pronounced. He began to paint murals and decorations on the walls of shops, kafenions (coffee houses), and private homes, often in exchange for a meager payment, a plate of food, or a glass of wine. His canvases were the humble surfaces of everyday life – walls, wooden panels, pieces of cardboard, or whatever material came to hand. This practice of painting directly in public spaces made his art accessible, though not always appreciated by the more sophisticated urbanites.

During his time in Volos and the surrounding region of Mount Pelion, Theofilos also engaged in organizing and participating in popular theatrical performances for national holidays and carnivals. He would often take on heroic roles, dressing as Alexander the Great or heroes from the Greek Revolution, such as Markos Botsaris or Athanasios Diakos. These performances were an extension of his artistic concerns, bringing to life the historical and mythical narratives that he so passionately depicted in his paintings. His life was a performance of sorts, embodying the spirit of the traditions he sought to preserve.

The Pelion Years: Poverty and Prolific Creation

The years Theofilos spent in the villages of Mount Pelion were marked by extreme poverty but also by intense artistic productivity. He lived a solitary and often itinerant life, moving from village to village, seeking commissions. The landscapes of Pelion, with their lush vegetation and traditional architecture, provided a rich backdrop for his imagination. He adorned the walls of houses in Ano Volos, Anakasia, and Makrinitsa with scenes from Greek history, mythology, and rural life.

One famous anecdote from this period illustrates the precariousness of his existence and the sometimes cruel reception he faced. While painting on a ladder in a Volos coffee house, he was reportedly teased and shaken by patrons, causing him to fall. This incident, or a similar one, is said to have deeply affected him, prompting his departure from Volos around 1927 and his return to his native Lesbos.

Despite the hardships, his commitment to his art never wavered. He painted with an almost compulsive energy, driven by an inner need to give form to the stories and images that filled his mind. His subjects were drawn from a deep well of Greek culture: the exploits of Alexander the Great, the heroes of the War of Independence, scenes from classical mythology (the labors of Hercules, figures like Achilles), Byzantine emperors, and idyllic portrayals of pastoral life, shepherds, farmers, and local festivals. He also depicted contemporary events and figures, albeit through his characteristic folk lens.

Artistic Style: Naïveté, Vibrancy, and Narrative Power

Theofilos Hadjimichail is considered one of the foremost exponents of Greek naïve art, a style often characterized by a disregard for academic rules of perspective, proportion, and anatomy, in favor of directness, vibrant color, and a strong narrative impulse. His paintings possess an undeniable charm and sincerity, stemming from his untutored approach and his profound connection to his subject matter.

His compositions are often frontal and two-dimensional, reminiscent of Byzantine icons or folk embroidery. Figures are clearly delineated, with strong outlines and flat areas of color. Perspective is intuitive rather than systematic, and there's often a hierarchical scaling where more important figures are depicted larger. Despite these "naïve" qualities, or perhaps because of them, his works exude a powerful vitality.

Color is a key element in Theofilos's art. He used bright, often unmixed colors, applying them with a boldness that gives his paintings an immediate visual impact. Blues, reds, greens, and yellows dominate his palette, creating a world that is both real and fantastical. His landscapes, while not always topographically accurate, capture the essence of the Greek environment – the clear light, the rugged mountains, the azure sea.

His figures, though sometimes stiff or awkwardly posed, are full of character and emotion. Whether depicting a fierce battle scene or a tranquil pastoral moment, Theofilos imbued his subjects with a sense of life and drama. He paid close attention to details of costume, weaponry, and local customs, reflecting his deep knowledge of and respect for Greek tradition. His work can be seen as a visual encyclopedia of Hellenic culture, as he understood and experienced it.

This style was distinct from the prevailing academic trends in Greek art of his time, which were largely influenced by the Munich School, exemplified by artists like Nikolaos Gyzis and Nikiforos Lytras, who focused on historical genre scenes and portraiture with a polished, realistic technique. Theofilos’s work also stood apart from the emerging modernist currents that would later be championed by artists like Konstantinos Parthenis or Giorgios Bouzianis.

Key Representative Works

Theofilos produced a vast body of work, much of it murals that have unfortunately been lost or damaged over time. However, many paintings on wood, canvas, and cardboard survive, showcasing the breadth of his thematic concerns.

"Erotokritos and Aretousa": This subject, drawn from the famous 17th-century Cretan romance poem by Vitsentzos Kornaros, was a favorite of Theofilos. He depicted the lovers in various scenes, capturing the chivalric and romantic spirit of the epic. These paintings highlight his narrative skill and his ability to convey emotion through simple, direct means.

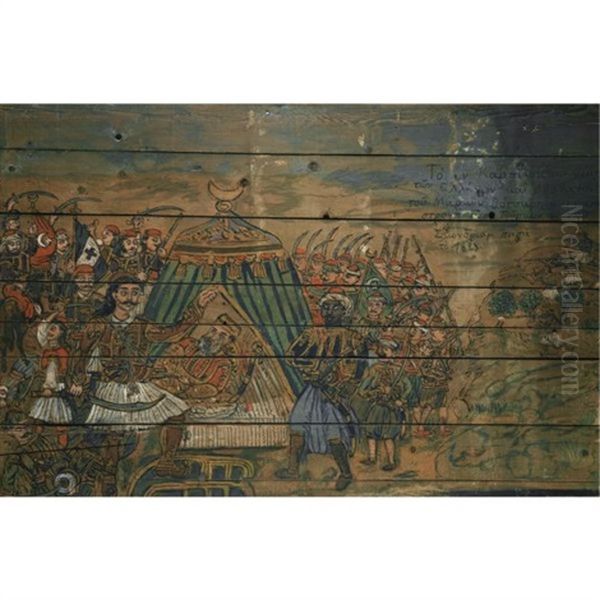

"Alexander the Great": The figure of Alexander the Great held a particular fascination for Theofilos, as he did for many Greeks, symbolizing military prowess and the spread of Hellenic civilization. Theofilos painted numerous scenes from Alexander's life, including his battles, his taming of Bucephalus, and his encounters with mythical creatures. These works are often dynamic and filled with action.

Scenes from the Greek War of Independence: Theofilos was deeply patriotic, and the heroes and battles of the 1821 revolution were a recurrent theme. He painted portraits of figures like Theodoros Kolokotronis, Georgios Karaiskakis, and Markos Botsaris, as well as dramatic depictions of key battles, such as the "Battle of Kalambaka" or the "Naval Battle of Navarino." These works served as visual reminders of Greece's struggle for freedom.

"Eleftherios Venizelos and King Constantine I": Theofilos also depicted contemporary political figures, reflecting the turbulent political landscape of early 20th-century Greece. His portrayals of prominent leaders like Eleftherios Venizelos, a dominant political figure, often carried symbolic weight, reflecting popular sentiments.

Pastoral Scenes and Daily Life: Alongside these grand historical and mythical themes, Theofilos painted numerous scenes of everyday rural life: shepherds with their flocks, farmers tilling the land, village festivals, and portraits of local people. These works reveal his deep affection for the simple, traditional way of life that was rapidly changing.

His work can be compared in spirit, if not always in style, to other naïve artists internationally, such as the French painter Henri Rousseau, who also created imaginative and vibrant worlds outside the academic mainstream.

The "Discovery" by Tériade and International Recognition

For most of his life, Theofilos worked in relative obscurity, appreciated by some locals but largely ignored or dismissed by the established art world. His fortunes, or at least his posthumous reputation, began to change in the late 1920s and early 1930s, thanks to the efforts of Stratis Eleftheriadis, better known as Tériade.

Tériade (1897-1983) was a highly influential art critic, publisher, and collector, also from Mytilene, Lesbos, who had moved to Paris and became a central figure in the modernist art scene. He championed many of the leading artists of the 20th century, including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, and Fernand Léger, through his luxurious art review "Verve" and his limited-edition art books (livres d'artiste).

Tériade recognized the unique genius of Theofilos's work, seeing in its apparent simplicity a profound authenticity and a direct connection to the wellsprings of Greek culture. He began to collect Theofilos's paintings and commissioned works from him. This patronage provided Theofilos with some financial stability in his final years, though he continued to live modestly. Tériade's advocacy was crucial in bringing Theofilos's art to the attention of a wider, more sophisticated audience, both in Greece and internationally.

Theofilos Hadjimichail passed away on March 24, 1934, in his native Vareia, Lesbos, reportedly from food poisoning. He was around 64 years old. At the time of his death, his recognition was still nascent.

It was Tériade's posthumous efforts that truly cemented Theofilos's reputation. He organized major exhibitions of Theofilos's work, including a landmark show at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1961 and another at the Kunsthalle Bern in Switzerland in 1960. These exhibitions introduced Theofilos to an international audience and positioned him as a significant figure in the world of modern naïve art. Critics and artists, including the renowned architect Le Corbusier and the painter Raymond Queneau (though Raymond Maurice was mentioned in the prompt, Queneau, a writer and painter associated with Surrealism, is more likely in Tériade's circle), praised the freshness and power of his vision.

The Greek Art Scene in Theofilos's Time

To fully appreciate Theofilos's unique position, it's helpful to understand the broader context of Greek art during his lifetime. The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of significant transition for Greece, which was striving to establish a modern national identity after centuries of Ottoman rule.

The official art world was dominated by the "Munich School," a group of Greek artists trained at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. Artists like Theodoros Vryzakis, Konstantinos Volanakis (known for his seascapes), and the aforementioned Gyzis and Lytras, brought a German academic style to Greece, focusing on historical themes, portraiture, and genre scenes. Their work was technically proficient and played an important role in shaping a national artistic narrative.

By the early 20th century, new currents began to emerge. Artists like Konstantinos Parthenis started to break away from academicism, incorporating elements of Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and Post-Impressionism. The "Generation of the '30s," which included painters like Yannis Tsarouchis, Nikos Engonopoulos, Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, and the poet-painter Andreas Embirikos, sought to combine modernist influences with a renewed interest in Greek tradition, including Byzantine art, folk art, and the works of Theofilos himself. For these artists, Theofilos represented an authentic, uncorrupted expression of the Greek spirit. Tsarouchis, in particular, was deeply influenced by Theofilos, admiring his directness and his ability to capture the essence of Greek life.

Theofilos, therefore, operated largely outside these mainstream developments. He was not part of any school or movement, yet his work resonated deeply with the quest for "Greekness" (Ελληνικότητα - Ellinikotita) that preoccupied many intellectuals and artists of his time. His art provided a visual link to a living folk tradition that was seen as a vital source of national identity.

Influence on Later Generations and Enduring Legacy

Theofilos Hadjimichail's influence on subsequent generations of Greek artists has been profound and multifaceted. He is widely regarded as the most important modern Greek folk painter and a key figure in the development of modern Greek art.

Artists of the "Generation of the '30s" and beyond saw in Theofilos a model of how to engage with Greek tradition in a way that was both authentic and modern. His work demonstrated that "Greekness" could be found not only in classical antiquity but also in the living culture of the people. His bold use of color, his narrative directness, and his unapologetic embrace of popular themes offered an alternative to both academic conservatism and uncritical imitation of Western European avant-gardes.

Painters like Yannis Tsarouchis explicitly acknowledged their debt to Theofilos, incorporating elements of his style and subject matter into their own sophisticated modernist idioms. Tsarouchis, known for his depictions of sailors, soldiers, and scenes from Greek popular life, shared Theofilos's interest in the foustanella and the heroic male figure. Similarly, Surrealist painters like Nikos Engonopoulos found inspiration in Theofilos's imaginative compositions and his fusion of myth and reality. Even the internationally acclaimed Greek-Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico, though stylistically very different, shared a deep connection to Greek mythology that resonates with Theofilos's thematic world.

Theofilos's legacy extends beyond the realm of fine art. His work has become an integral part of Greek popular culture, reproduced on posters, calendars, and everyday objects. He is celebrated as a national hero, a symbol of artistic integrity and unwavering dedication to Greek tradition.

Preservation of a National Treasure

The preservation of Theofilos Hadjimichail's artistic heritage has been a significant concern. Thanks largely to the efforts of Tériade, a substantial body of his work has been saved and is now accessible to the public.

In 1964, Tériade financed the construction of the Theofilos Museum in Vareia, Lesbos, the painter's birthplace. The museum was built on the site of the Hadjimichail family home and houses 86 of Theofilos's paintings from Tériade's personal collection. This museum stands as a permanent tribute to the artist and is a major cultural attraction on the island.

Another important institution is the Tériade Museum-Library of Stratis Eleftheriadis, also in Vareia, Mytilene, established in 1979. While it primarily showcases Tériade's remarkable collection of illustrated books by 20th-century masters, it also contextualizes Theofilos within the broader artistic milieu that Tériade championed.

Many of Theofilos's works are also held in private collections and other public museums in Greece, including the National Gallery in Athens and the Municipal Art Gallery of Larissa, which holds a significant collection. Some of his murals, though fragile, still survive in situ in Pelion and Mytilene, offering a direct glimpse into his working methods and the environments he transformed with his art. The Greek state has also honored him; for instance, the Bank of Greece has featured his work on commemorative coins, such as a 1 Euro coin, further cementing his status as a national cultural icon.

Historical Evaluation and Conclusion

Theofilos Hadjimichail's journey from a marginalized folk painter to a celebrated national artist is a remarkable story. Initially dismissed by many of his contemporaries as an eccentric and untalented amateur, his true worth was gradually recognized, thanks to the perspicacity of figures like Tériade and the embrace of later generations of artists.

Today, Theofilos is revered as a vital link in the chain of Greek artistic tradition. His work is seen as a bridge between the anonymous folk artisans of the past and the self-conscious modern artists who sought to define a contemporary Greek identity. He demonstrated that art could be found not only in academies and salons but also in the streets, kafenions, and homes of ordinary people.

His paintings are more than just charming depictions of Greek life; they are historical documents, cultural artifacts, and expressions of a profound spiritual connection to his homeland. They capture the resilience, pride, and imaginative richness of the Greek spirit. In a world increasingly dominated by globalization and cultural homogenization, Theofilos's art reminds us of the importance of local traditions and the power of individual vision. His brushstrokes, though often described as "naïve," possess a wisdom and an emotional depth that continue to resonate with audiences today, securing his place as an enduring and beloved figure in the pantheon of Greek art. His life and work serve as an inspiration, proving that true artistry can flourish even in the face of adversity and misunderstanding, ultimately finding its rightful place in the cultural heritage of a nation.