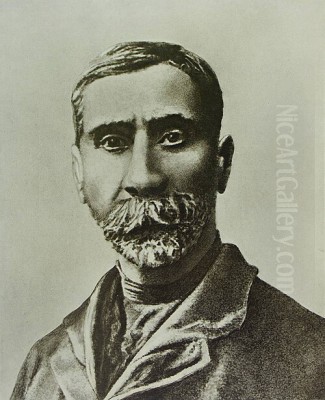

Niko Pirosmanashvili, often known simply as Pirosmani, stands as one of Georgia's most celebrated and enigmatic artistic figures. A self-taught painter, his work emerged from the vibrant, everyday life of Tbilisi at the turn of the 20th century, capturing its characters, traditions, and landscapes with a raw, intuitive power. Despite a life marked by poverty and a lack of formal recognition during his lifetime, Pirosmani's unique vision has posthumously earned him international acclaim, positioning him as a pivotal figure in the Primitivist movement and a cherished national icon. His paintings, characterized by their bold simplicity, expressive figures, and often dark, evocative backgrounds, offer a profound window into the soul of Georgia.

A Humble Beginning in Kakheti

Nikoloz Aslanis Dze Pirosmanashvili was born on May 5, 1862, in the village of Mirzaani, nestled in the Kakheti region of eastern Georgia, an area renowned for its vineyards and ancient winemaking traditions. His family were peasants, owning a small vineyard and some livestock, and his early life was steeped in the rhythms of rural existence. This connection to the land and its simple verities would later permeate his artistic themes.

Tragedy struck early in Niko's life. He was orphaned at a young age, losing both his parents, Aslan Pirosmanashvili and Tekle Toklikishvili. The responsibility for his upbringing fell to his two elder sisters, Mariam and Peputsa. Around 1870, the sisters, along with young Niko, relocated to Tbilisi, the bustling capital of Georgia, in search of better opportunities. This move marked a significant shift from the pastoral tranquility of Mirzaani to the dynamic, multicultural environment of a growing city.

Tbilisi: A Crucible of Experience

In Tbilisi, the young Pirosmani was exposed to a world far removed from his village origins. He initially found work in the households of wealthy families, including the Kalantarovs, where he learned to read and write in both Georgian and Russian. Despite this informal education, he never received any formal artistic training. His artistic inclinations, however, were strong and irrepressible.

Pirosmani was a keen observer of life around him. He absorbed the sights and sounds of Tbilisi – its bustling bazaars, its lively taverns (dukhanis), its diverse populace of merchants, artisans, aristocrats, and common folk. He reportedly learned to paint by watching itinerant sign painters and other street artists, gradually developing his own distinctive style through practice and innate talent.

Throughout his adult life, Pirosmani struggled with persistent poverty. He attempted various ventures to secure a livelihood, none of which brought lasting financial stability. For a time, he worked as a railway conductor, a job that allowed him to travel and observe different facets of Georgian life. Later, in partnership with another self-taught painter, Gigo Zaziashvili, he tried his hand at sign painting, opening a workshop to create shop signs and decorative panels. He even attempted to run a dairy farm, but this too ultimately failed.

His lack of business acumen and perhaps a temperament unsuited to sustained commercial enterprise meant that he often lived a hand-to-mouth existence. He remained unmarried and led a largely itinerant life, often finding food and shelter in exchange for his paintings, particularly in the dukhanis and small restaurants of Tbilisi. These establishments became both his patrons and his exhibition spaces.

The Unique Artistic Vision of Pirosmani

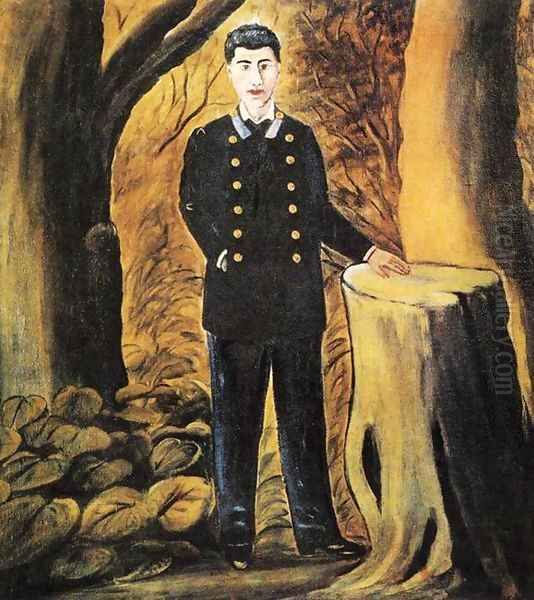

Pirosmani's art is instantly recognizable for its directness, sincerity, and profound connection to his environment. He developed a unique approach, often painting on unconventional materials like black oilcloth, tin sheets, or simple cardboard, likely due to the scarcity and cost of traditional canvases. The black oilcloth, in particular, became a signature element, its dark surface providing a dramatic backdrop that made his figures and objects emerge with striking intensity.

Style and Technique

His style is classified as Primitivist or Naïve. Lacking formal academic training, Pirosmani was unburdened by artistic conventions and theories. This allowed him to develop a visual language that was entirely his own, characterized by:

Simplified Forms: Figures and objects are often rendered with bold outlines and a lack of complex perspective or anatomical precision. This simplification, however, does not detract from their expressiveness; rather, it enhances their iconic quality.

Flatness of Space: Pirosmani generally avoided deep perspectival space, often arranging his subjects frontally or in profile, reminiscent of ancient frescoes or folk art. This creates a sense of immediacy and direct engagement with the viewer.

Bold Color Palette: While his backgrounds were often dark, the subjects themselves were painted in strong, often unmixed colors. Reds, yellows, blues, and whites feature prominently, applied with a directness that conveys emotion and vitality.

Compositional Clarity: His compositions are typically straightforward and balanced, focusing attention on the central subject matter. There is an inherent monumentality even in his smaller works.

Emotional Resonance: Despite the apparent simplicity, Pirosmani's paintings are imbued with a deep sense of feeling – sometimes joy and celebration, other times melancholy or a quiet dignity. He had an uncanny ability to capture the essence of his subjects.

Dominant Themes

Pirosmani's subject matter was drawn directly from the world around him and the collective memory of his culture:

Portraits: He painted numerous portraits of shopkeepers, artisans, noblemen, and ordinary citizens of Tbilisi. These are not merely likenesses but character studies, often conveying the sitter's social standing and personality with a few deft strokes. His Portrait of Ilya Zdanevich is a notable example.

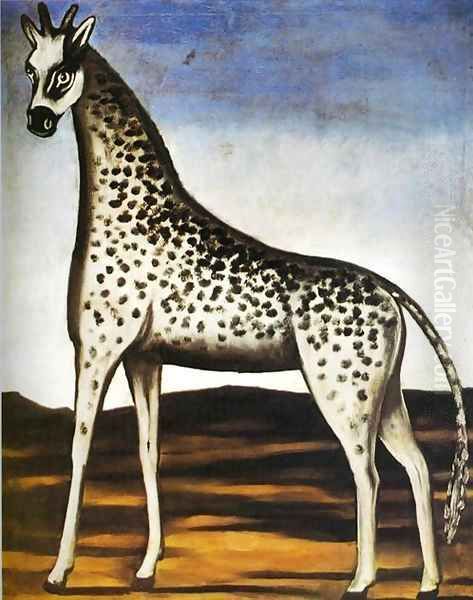

Animals: Animals feature prominently in his oeuvre, depicted with a unique blend of realism and stylization. Lions, deer, giraffes, bears, and domestic animals are rendered with a sense of empathy and an almost totemic presence. His Giraffe and White Bear with Cubs are iconic.

Feasts and Celebrations (Supras): The Georgian tradition of feasting (supra) is a recurring theme, reflecting the importance of hospitality and communal gathering in Georgian culture. Paintings like Feast of Five Princes or Company on a Cart during Easter Day capture the conviviality and abundance of these occasions.

Rural Life and Labor: Scenes of peasants working, shepherds with their flocks, and depictions of harvests reflect his Kakhetian roots and an appreciation for the agrarian way of life. Threshing Floor, Kakhetian Vintage, and Peasant Woman with Children Going for Water exemplify this.

Urban Scenes and Taverns: As a frequenter of Tbilisi's dukhanis, he often depicted scenes from these establishments – musicians, dancers, patrons enjoying themselves. Tavern Scene or Company with a Gramophone are lively examples.

Historical and Legendary Figures: Occasionally, Pirosmani would paint figures from Georgian history or legend, such as Queen Tamar or Shota Rustaveli, treating them with the same directness as his contemporary subjects.

Still Lifes: He also produced still lifes, often featuring food, wine, and everyday objects, painted with a simple, unpretentious charm. Still Life with a Samovar is an example.

Representative Masterpieces

While it is difficult to single out works from such a consistent and unique body of art, several paintings are frequently cited as quintessential Pirosmani:

Actress Marguerite de Sèvres: This painting is linked to one ofthe most famous legends surrounding Pirosmani. It depicts a French singer or actress who visited Tbilisi. The story, popularized in a song and later a film, tells of Pirosmani, smitten by her beauty, selling all his possessions to buy a sea of flowers to lay before her hotel. The painting itself is a striking portrait, capturing an enigmatic elegance.

The Fisherman in a Red Shirt (Red Shirted Fisherman): A powerful and iconic image, this painting shows a solitary fisherman, his red shirt a vibrant splash against a dark, moody landscape. The figure possesses a quiet dignity and strength.

Giraffe: One of his most beloved animal paintings, the giraffe is depicted with a charming naivety, its elongated form set against a sparse, dreamlike landscape. It evokes a sense of wonder and the exotic.

Arsenal Hill at Night: This work captures a nocturnal view of a part of Tbilisi, with figures silhouetted against the glow of lights. It demonstrates his ability to create atmosphere and mood with minimal means.

Feast of Five Princes: A classic example of his supra scenes, this painting depicts a group of noblemen feasting, rendered with his characteristic frontal composition and attention to the details of the table setting.

Georgian Woman Wearing a Lechaki: A dignified portrait that captures traditional Georgian attire and a sense of timeless grace.

Deer Drinking Water: A serene and almost mystical depiction of a deer in a tranquil, natural setting, showcasing his affinity for animal subjects.

Old-Time Georgian Wedding: This work captures the ceremonial and communal aspects of a traditional Georgian wedding, filled with figures and details that evoke a specific cultural moment.

These works, among many others, showcase the breadth of his thematic concerns and the consistency of his unique artistic language.

A Fleeting Glimpse of Recognition

During most ofhis life, Pirosmani's art was appreciated primarily by the patrons of the taverns and shops he decorated. He was a local figure, a "painter for the people," rather than an artist recognized by the established art circles. However, there was a brief period when his work caught the attention of a more avant-garde group.

In 1912, his paintings were "discovered" by the Russian Futurist poet Ilya Zdanevich (who adopted the pseudonym Iliazd) and his brother, the artist Kirill Zdanevich, along with the artist Mikhail Le-Dantyu. They were captivated by the raw power and originality of Pirosmani's work, seeing in it an authentic expression that resonated with their own modernist sensibilities. Ilya Zdanevich, in particular, became a champion of Pirosmani, collecting his works and writing about him.

Through the efforts of the Zdanevich brothers and Le-Dantyu, some of Pirosmani's paintings were included in the "Target" (Mishen) exhibition in Moscow in March 1913. This exhibition was a significant event for the Russian avant-garde, featuring works by prominent artists such as Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov (founders of Rayonism and organizers of the exhibition), Kazimir Malevich, and Marc Chagall. The inclusion of Pirosmani alongside these leading figures was a remarkable, if fleeting, moment of wider exposure.

Articles about him appeared in the Georgian press, and he was even invited to join the Society of Georgian Painters in 1916. However, Pirosmani, perhaps wary of formal associations or misunderstood by some of its members who may have viewed his work with condescension, reportedly attended only one meeting and then distanced himself. He was caricatured in a newspaper, an incident that deeply wounded him. This brief brush with the art world did little to alleviate his poverty or change his solitary lifestyle.

The Legend of Marguerite and the "Million Roses"

One of the most enduring and romanticized stories associated with Pirosmani is his infatuation with a French singer or actress named Marguerite de Sèvres, who was performing in Tbilisi. According to the legend, Pirosmani, deeply enamored, sold everything he owned, including his small shop and painting supplies, to buy an immense quantity of flowers – roses are often specified – and had them delivered to her hotel, filling the street outside her window.

The grand gesture, however, did not win him her lasting affection. Marguerite soon left Tbilisi, and Pirosmani was left heartbroken and destitute. This story, whether entirely factual or embellished over time, has become a powerful symbol of the artist's passionate nature and his unrequited love. It inspired the famous Russian song "Million Alykh Roz" (A Million Scarlet Roses) and has been depicted in films about his life. His painting, Actress Marguerite, is often seen as a poignant memento of this episode.

Final Years, Death, and Obscurity

Despite the brief flicker of attention from the avant-garde, Pirosmani's final years were marked by continued hardship, loneliness, and declining health. The turmoil of World War I and the Russian Revolution further destabilized the region, making life even more precarious for a struggling artist.

Niko Pirosmanashvili died in the spring of 1918, likely on April 9th, though some sources suggest slightly different dates. He succumbed to malnutrition and liver failure, a tragic end for an artist of such profound talent. He was found ill in a damp cellar beneath a staircase on Molokanskaya Street (now Pirosmani Street) and taken to a hospital, where he passed away a few days later. He was approximately 55 or 56 years old.

His death went largely unnoticed. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the Kukiiskoe Cemetery in Tbilisi. The exact location of his grave remains unknown, adding another layer of poignancy to his life story. For several decades after his death, Pirosmani and his art faded back into relative obscurity, cherished by a few collectors but largely unknown to the wider world.

Posthumous Renaissance and International Acclaim

The true rediscovery and appreciation of Niko Pirosmani's genius began in the mid-20th century. Art historians and critics, particularly in Georgia and then Russia, began to recognize the unique power and significance of his work. His paintings were sought out, collected, and studied.

A major turning point came with a large posthumous exhibition of his works in Tbilisi in 1929, and later, his inclusion in exhibitions of Georgian art. The establishment of the Shalva Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts (part of the Georgian National Museum) in Tbilisi provided a permanent home for many of his surviving works, estimated to be around 200 paintings.

International recognition grew steadily. His art was seen as a remarkable example of Primitivism, comparable in its intuitive power to the work of the French self-taught master Henri Rousseau (Le Douanier Rousseau). Pirosmani's directness, his ability to distill emotion and character, and his authentic connection to his cultural roots resonated with a growing appreciation for non-academic art forms.

Exhibitions of his work began to travel beyond the Soviet Union. A particularly significant event was the 1969 exhibition at the Louvre in Paris, which introduced his art to a Western European audience and solidified his international reputation. This was a remarkable journey for an artist who had died in poverty and obscurity.

The renowned artist Pablo Picasso was reportedly an admirer of Pirosmani's work. After seeing reproductions of Pirosmani's paintings, Picasso is said to have made an etching titled Portrait of Pirosmani in 1972, a testament to the Georgian artist's appeal to one of the giants of 20th-century art.

Pirosmani's influence can also be seen in the work of later Georgian artists, such as Lado Gudiashvili and David Kakabadze, who, while developing their own distinct styles, shared a deep connection to Georgian traditions and a modernist sensibility. The raw authenticity of Pirosmani's vision provided an inspiring counterpoint to more academic approaches. Other artists who might have found resonance with his spirit, if not direct influence, could include figures like Amedeo Modigliani, known for his stylized portraits and bohemian life, or even earlier figures like Vincent van Gogh, whose emotional intensity and connection to everyday subjects offer a parallel. The directness of his work also prefigures some aspects of Art Brut, championed by Jean Dubuffet.

Pirosmani's Enduring Legacy

Today, Niko Pirosmani is revered as a national treasure in Georgia. His life story, a blend of artistic triumph and personal tragedy, has become legendary. His paintings are celebrated for their profound humanity and their timeless depiction of Georgian life and spirit.

Cultural Icon: Pirosmani Street in Tbilisi is named in his honor, and a monument to him stands in the city. His birthplace in Mirzaani is now a house-museum dedicated to his life and work.

Artistic Influence: He is considered a foundational figure in modern Georgian art. His work demonstrated that profound artistic expression could emerge from outside the confines of academic training, valuing intuition and direct experience. His influence extends to the broader understanding of Primitivist art globally.

Inspiration for Other Arts: His life and art have inspired numerous poems, songs (most famously "A Million Scarlet Roses"), plays, and films, including Giorgi Shengelaia's acclaimed 1969 biographical film Pirosmani.

Symbol of Authenticity: In an increasingly globalized world, Pirosmani's art stands as a powerful testament to the value of local culture and individual vision. His unwavering commitment to his own way of seeing, despite a lack of contemporary reward, offers an enduring lesson.

The art of Niko Pirosmanashvili transcends its humble origins. It speaks a universal language of emotion, observation, and cultural identity. He painted the world as he saw it, with an honesty and directness that continues to captivate and move audiences. From the taverns of old Tbilisi to the galleries of the world, the untamed genius of Pirosmani endures, a vibrant and essential voice in the chorus of art history. His legacy is a reminder that true artistry can blossom in the most unexpected places, nourished by an unwavering connection to life itself. His work continues to be studied and admired, ensuring that the painter who lived in poverty and died in obscurity remains a luminous figure for generations to come.