Thomas Fearnley stands as a pivotal figure in the golden age of Norwegian painting. A leading exponent of national Romanticism, his life and work bridged the wild landscapes of his homeland with the artistic currents of continental Europe. Born into a Norway finding its modern identity, Fearnley developed a profound connection to nature, translating its grandeur, beauty, and sometimes untamed spirit onto canvas with remarkable sensitivity and technical skill. His extensive travels and studies abroad enriched his perspective, allowing him to fuse Nordic sensibilities with broader European artistic traditions, leaving an indelible mark on Scandinavian art history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Norway

Thomas Fearnley was born on December 27, 1802, in Fredrikshald (now Halden), Norway, near the Swedish border. His family background connected him to the merchant class. An anecdote recalls him spending his fifth birthday with his aunt and uncle in Christiania (now Oslo), suggesting early exposure to the capital city. His initial path seemed destined for a military career, but his time at the War School was cut short around the age of 17 due to disciplinary issues. This deviation proved fortuitous for the art world.

Instead of pursuing military life, Fearnley enrolled in the newly established Tegneskolen (The Norwegian National Academy of Craft and Art Industry) in Christiania in 1819. He studied there until 1821, quickly demonstrating a natural aptitude for drawing and painting. It was during this period that his talent began to gain recognition. His works were first shown publicly at one of the Drawing School's exhibitions, placing him in the company of established figures like Johannes Flintoe and the already renowned Johan Christian Dahl (J.C. Dahl), who would later become a crucial mentor.

These early years in Norway laid the foundation for his lifelong fascination with landscape. The dramatic fjords, dense forests, and powerful waterfalls of his homeland provided initial inspiration. Even at this stage, his work hinted at the keen observational skills and the developing interest in capturing the effects of light and atmosphere that would characterize his mature style. His time at the Tegneskolen provided him with essential technical grounding before he sought further refinement abroad.

Formative Travels and Studies Abroad

Seeking broader artistic horizons, Fearnley left Norway in 1821. His first significant stop was Copenhagen, a major artistic center in Scandinavia. From 1821 to 1823, he studied at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, where he received instruction from the landscape painter Jens Peter Møller. This period exposed him to the prevailing trends in Danish art and further honed his skills in landscape depiction, likely within a somewhat more classical or Biedermeier framework prevalent there.

After Copenhagen, Fearnley's travels continued. He spent time in Stockholm between 1823 and 1827, undertaking commissions, including some for the Swedish royal family. His work reportedly caused a stir during exhibitions there, indicating his growing reputation. His journeys also took him briefly to the Netherlands and London, exposing him to different artistic traditions, including the rich heritage of Dutch landscape painting and potentially the burgeoning landscape school in Britain, exemplified by artists like John Constable, whose approach to light and atmosphere may have resonated with Fearnley.

A pivotal moment in his development occurred in 1829 when he traveled to Dresden. There, he sought out his compatriot, the celebrated landscape painter Johan Christian Dahl, who had settled in the Saxon capital. Studying informally with Dahl proved transformative. Dahl, himself influenced by German Romanticism, particularly the atmospheric landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich, encouraged Fearnley to move beyond the more constrained style he had perhaps absorbed earlier.

Under Dahl's guidance, Fearnley embraced a freer, more painterly technique. He learned to apply oil paint more boldly, focusing intensely on capturing the transient effects of light, shadow, and weather. Dahl, who considered Fearnley one of his most gifted pupils, instilled in him a deeper appreciation for the expressive potential of landscape and reinforced the Romantic emphasis on subjective experience and the sublime power of nature. This period in Dresden was crucial in shaping Fearnley's mature artistic vision.

The Romantic Vision: Landscape as Subject

Thomas Fearnley's art is firmly rooted in the Romantic movement, yet it possesses a distinct character that blends dramatic sensibility with careful observation. He shared the Romantic fascination with the power and beauty of nature, often depicting scenes of majestic mountains, cascading waterfalls, and serene lakes. However, his work often avoids the overt symbolism or mystical qualities found in some German Romantics like Caspar David Friedrich, leaning instead towards a more direct, albeit heightened, representation of the natural world.

His style is often described as a fusion of Romanticism and Realism. While he sought to convey the emotional impact of a landscape – its grandeur, tranquility, or wildness – he did so through meticulous attention to detail, accurate rendering of topography, and a sophisticated understanding of light and color. He was a master at capturing the specific atmospheric conditions of a scene, whether the clear, crisp light of the Alps, the soft haze of an Italian morning, or the dramatic contrasts of a Norwegian storm.

Light plays a crucial role in his compositions. He skillfully used chiaroscuro (the contrast of light and dark) to create depth, drama, and focus. His palette could range from vibrant and warm, particularly in his Italian scenes, to cooler, more subdued tones in his Nordic or Alpine landscapes. His brushwork, influenced by Dahl, became increasingly fluid and expressive, capable of rendering both broad vistas and intricate details like foliage, rock formations, and water surfaces with convincing texture.

Fearnley often included small human figures in his vast landscapes. These figures typically serve to emphasize the scale and majesty of nature, inviting the viewer to contemplate the scene. This use of the Rückenfigur (a figure seen from behind), a motif famously employed by Caspar David Friedrich and also seen in the work of German contemporaries like Wilhelm von Kobell, appears in some of Fearnley's works, drawing the viewer into the depicted space and aligning their perspective with that of the figure contemplating the view.

Masterworks and Signature Themes

Fearnley's oeuvre includes several iconic paintings that exemplify his style and thematic concerns. Among his most celebrated works is The Grindelwald Glacier (1838). Painted during his travels in Switzerland, this masterpiece depicts the imposing lower Grindelwald glacier with breathtaking detail and atmospheric effect. The contrast between the sunlit peaks in the distance, the shadowed valley, and the intricate textures of the ice showcases his mastery of light and color. The inclusion of small figures gazing at the glacier underscores the sublime power of the Alpine landscape, and the work is considered a high point of Romantic landscape painting, effectively contrasting warm and cool tones.

Another significant Norwegian subject is Labrofossen (The Labro Waterfall, 1837). This painting captures the raw energy of a powerful waterfall near Kongsberg, Norway. Fearnley renders the churning water and surrounding cliffs with dynamic brushwork and dramatic lighting, conveying the untamed force of nature, a recurring theme in Nordic Romanticism. The painting demonstrates his ability to handle complex motion and texture while maintaining compositional harmony.

The Slinde Birch (Slindebirken, 1839) presents a different mood. This iconic work depicts a solitary, wind-blown birch tree perched precariously on a burial mound overlooking the Sognefjord. The painting is imbued with a sense of history, melancholy, and the resilience of life against the elements. It has become a symbol of Norwegian national identity and showcases Fearnley's ability to infuse landscape with emotional depth and narrative suggestion.

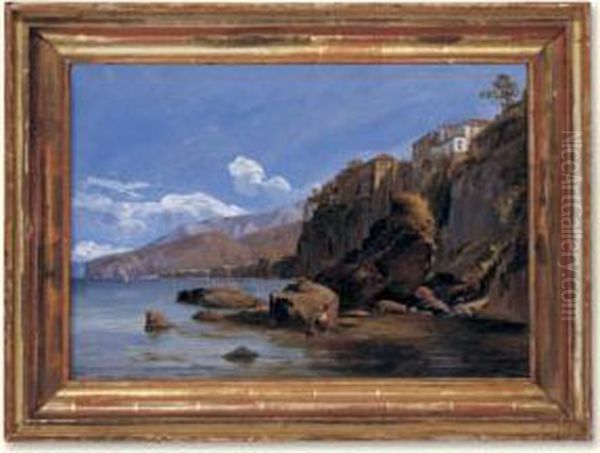

His Italian travels inspired works like Fishermen at Sorrento (ca. 1834). Here, the mood shifts to the sun-drenched Mediterranean. The painting captures the picturesque quality of the Italian coast, with warm light, clear waters, and local figures engaged in daily life. It reflects the allure Italy held for Northern European artists, offering different light conditions and subject matter. Similarly, paintings like Ramsau (1830), depicting a scene in the Bavarian Alps, show his engagement with the landscapes encountered during his travels in Germany.

Fearnley's work consistently revolved around the theme of nature, explored through various lenses: the sublime and dramatic (waterfalls, glaciers), the picturesque (Italian coasts, pastoral scenes), and the nationally significant (Norwegian fjords and landmarks). His dedication to landscape painting, informed by direct observation and enriched by his European experiences, cemented his place as a master of the genre.

Journeys Through Europe: Italy and Switzerland

Fearnley's extensive travels were not mere sightseeing excursions; they were integral to his artistic development and practice. After his formative time in Dresden, he embarked on a significant journey south, spending several years in Italy from 1832 to 1835. Italy, with its classical ruins, stunning coastlines, and unique quality of light, had long been a magnet for artists from across Europe. Fearnley immersed himself in this environment, traveling widely from Rome to Naples, Sicily, and the Amalfi Coast.

In Italy, he continued to refine his skills, particularly his handling of light and color. The Mediterranean sun offered a different challenge compared to the softer light of Northern Europe. Works from this period, such as views of Capri, Sorrento, and Sicilian temples, often display a brighter palette and a focus on architectural elements within the landscape. He diligently sketched outdoors, capturing immediate impressions that would later be worked up into finished paintings in the studio. This practice of plein air sketching was crucial for capturing authentic light effects and atmospheric nuances.

His travels also took him repeatedly to the Swiss Alps. The dramatic mountain scenery provided subjects perfectly suited to the Romantic sensibility. His trip to the Bernese Oberland in 1835, partly in the company of the Danish painter Wilhelm Bendz, was particularly fruitful. It was during this time that he gathered studies for his famous painting The Grindelwald Glacier. He climbed high into the mountains, sketching glaciers, peaks, and valleys, driven by a desire to experience and record these awe-inspiring landscapes firsthand.

These journeys fostered a cosmopolitan outlook. Fearnley moved within international artistic circles, particularly in Rome and Munich. In Munich, where he spent time after his Italian sojourn and again later in his life, he connected with German artists like Joseph Petzl and Christian Ezdorf. These interactions were part of a broader network of Nordic and German artists who traveled, studied, and exchanged ideas, contributing to a vibrant cross-cultural artistic dialogue during this period. His reputation grew, and he became known affectionately among Norwegians back home as "The European" due to his extensive travels and international connections.

The Practice of Plein Air Sketching

A vital aspect of Fearnley's working method, particularly during his travels, was his dedication to sketching directly from nature (en plein air). While finished exhibition pieces were typically completed in the studio, his numerous oil sketches and drawings made outdoors formed the essential foundation for these larger works. This practice aligned him with other progressive landscape painters of his era, like his mentor J.C. Dahl and the English painter John Constable, who emphasized direct observation as the basis for truthful representation.

Fearnley's plein air sketches are characterized by their freshness, immediacy, and focus on capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. Working quickly, often on paper or small boards, he used fluid brushstrokes and a keen sense of color to record his impressions. These sketches were not just preparatory studies; they possess an artistic vitality of their own, revealing his process of seeing and translating the visual world. They demonstrate his ability to analyze a scene rapidly, identifying key compositional elements and color relationships.

His choice of materials often reflected the practicalities of travel. He used various types of paper and portable sketching equipment, sometimes employing fixatives to protect drawings made on the move. This adaptability allowed him to work effectively in diverse environments, from the damp fjords of Norway to the sunny hills of Italy and the high altitudes of the Alps. His commitment to outdoor sketching places him as an important precursor to later movements like Impressionism, which would elevate the plein air sketch to the status of a finished work. For Fearnley, it was an indispensable tool for understanding and capturing the essence of the landscapes he depicted.

Connections and Contemporaries

Thomas Fearnley did not work in isolation. He was part of a dynamic network of artists, particularly during his time abroad. His relationship with Johan Christian Dahl was paramount. More than just a teacher-student dynamic, they shared a deep friendship and mutual respect. They traveled together in Norway, sketched side-by-side, and maintained correspondence. Dahl's influence is undeniable, yet Fearnley developed his own distinct artistic personality, sometimes favoring a more detailed realism compared to Dahl's broader, more atmospheric approach.

In Dresden and Munich, he interacted with numerous German Romantic and Biedermeier painters. His connection with figures like Caspar David Friedrich was likely indirect but significant through Dahl and the general artistic milieu in Dresden. He shared thematic interests, such as the Rückenfigur, with painters like Wilhelm von Kobell. His friendships with artists like Joseph Petzl and Christian Ezdorf in Munich placed him within the active South German art scene.

During his travels, he encountered artists from various nations. His journey to the Swiss Alps with the promising Danish painter Wilhelm Bendz, whose life was tragically cut short soon after, highlights the camaraderie and shared experiences among traveling artists. His early exhibition alongside Johannes Flintoe in Christiania connects him to the older generation of Norwegian landscape pioneers.

Fearnley's engagement with the broader European art world is also suggested by potential influences from artists like John Constable, whose naturalistic approach to landscape and focus on light effects were becoming known on the continent. Mention of interactions with French painters like François-Pierre Guillaume Patin further underscores his integration into international artistic circles. These connections enriched his art, exposing him to diverse styles and ideas, which he synthesized into his unique vision. His relationship with patrons, including the Swedish royal family for whom he undertook commissions, was also important for his career.

Later Years, Untimely Death, and Legacy

Fearnley returned to Norway periodically throughout his career, undertaking significant journeys through its dramatic landscapes, gathering material for major works like Labrofossen and The Slinde Birch. He also spent time in Amsterdam and London again in the late 1830s. He married Cecilie Catharine Andresen in 1839, the daughter of his patron, the banker Nicolai Andresen. They had one son, Thomas Nicolay Fearnley (1841–1927), who would become a prominent shipping magnate and art collector.

His reputation as one of Scandinavia's leading landscape painters was firmly established. He continued to travel, seeking new subjects and maintaining his connections with the European art world. In the early 1840s, he was based primarily in Munich. Tragically, his promising career was cut short. Thomas Fearnley died suddenly in Munich on January 16, 1842, at the young age of 39. The cause of death is often cited as typhoid fever or possibly pleurisy.

Despite his relatively short life, Thomas Fearnley left a significant legacy. He is considered, alongside J.C. Dahl, one of the founding fathers of the Norwegian national school of landscape painting. His works captured the unique character of the Norwegian landscape with unprecedented skill and sensitivity, contributing to a growing sense of national identity in the 19th century. His technical mastery, particularly his handling of light and detail, set a high standard for subsequent generations of Norwegian artists.

His influence extended beyond Norway. As a key figure bridging German Romanticism and a more naturalistic approach, his work holds importance in the broader context of European landscape painting. His pioneering use of plein air sketching contributed to the development of observational practices that would become central to Impressionism later in the century. Artists like Gustave Caillebotte, working decades later, continued the tradition of using compositional devices like the Rückenfigur, a lineage that can be traced back through Dahl and Fearnley to Friedrich. The themes of nature's power and the human response to it, so central to Fearnley's work, continued to resonate with later artists, including Impressionists like Claude Monet who explored similar motifs of light, water, and atmosphere.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Thomas Fearnley remains a cornerstone of Norwegian art history. His journey from the Tegneskolen in Christiania to the major art centers of Europe reflects the ambition and talent that characterized the burgeoning artistic life of his nation. He absorbed influences from mentors like J.C. Dahl and contemporaries across Europe, yet forged a distinctive style marked by romantic sensibility, keen observation, and technical brilliance.

His depictions of the Norwegian wilderness, the Italian sunshine, and the Alpine sublime continue to captivate viewers with their blend of grandeur and intimacy. Through works like The Grindelwald Glacier, Labrofossen, and The Slinde Birch, he not only documented landscapes but also explored the profound relationship between humanity and the natural world. His dedication to plein air sketching marked him as a forward-looking artist, anticipating later developments in landscape painting. Though his life was tragically brief, Thomas Fearnley's vision endures, securing his place as a master of European Romantic landscape painting and a vital figure in the cultural heritage of Norway.