John Fery stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the grand narrative of American landscape painting. Active during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this Austrian-born artist captured the sublime beauty and rugged majesty of the American West, particularly the Rocky Mountains, with a prolificacy and distinctive style that left an indelible mark on the region's visual identity. His canvases, often vast and imbued with dramatic light, served not only as artistic expressions but also as powerful promotional tools, shaping the public's perception of newly accessible wilderness areas and contributing to the burgeoning tourism industry fostered by the great railway lines. Fery's life and work bridge European artistic training with the raw inspiration of the American frontier, creating a legacy intertwined with the landscapes he so passionately depicted.

European Roots and Artistic Formation

John Fery, originally Johann Nepomuk Levy, was born in 1859 in Straßwalchen, near Salzburg, in the Austrian Empire. His early life unfolded against the backdrop of Central Europe's rich artistic traditions. Details about his earliest training are somewhat sparse, but it is known that he received formal art education, likely honing his skills in academies that emphasized technical proficiency and observation. Sources indicate studies in cities like Vienna and possibly Munich, major artistic hubs of the era. He also reportedly studied in Pressburg (modern-day Bratislava, Slovakia). This European grounding would have exposed him to various artistic movements, including the lingering influence of Romanticism and the burgeoning currents of Realism and Impressionism that were transforming European art.

During his time in Europe, Fery developed a keen eye for landscape. He spent time in Switzerland, a country renowned for its own dramatic alpine scenery, which may have prefigured his later fascination with the Rockies. It was also in Europe, likely Switzerland, that he met and married Mary Rose Kraemer. Together, they started a family, eventually having three children. This period established the foundations of his artistic practice and personal life before the pivotal decision to seek new horizons across the Atlantic. His European experiences undoubtedly shaped his perspective, providing him with the technical skills and artistic sensibilities he would later adapt to the unique challenges and inspirations of the American West.

Emigration and the Call of the American West

The exact motivations for Fery's emigration remain somewhat speculative, but like many Europeans of his time, he was likely drawn by the promise of opportunity and perhaps the allure of the vast, untamed landscapes described in accounts filtering back to the Old World. In 1883, according to some sources, or around 1890 according to others provided in the initial summary, John Fery made the life-altering journey to the United States. This move marked the beginning of the most significant phase of his artistic career. The American West, with its monumental scale, dramatic geology, and unique atmospheric conditions, offered a subject matter vastly different from the European Alps.

He initially spent time in various locations, possibly including the East Coast or Midwest, perhaps seeking commissions or connections. However, his destiny lay westward. He eventually settled near what would become Glacier National Park in Montana. This region, with its jagged peaks, pristine lakes, and dense forests, became a primary source of inspiration for decades. The move to the West was not just a geographical relocation; it was an immersion into a landscape that would define his artistic identity and provide the subject matter for his most famous works. The timing was opportune, coinciding with the expansion of railways and a growing national interest in preserving and promoting these natural wonders.

The Railway Commissions: A Defining Partnership

A crucial element of John Fery's career in America was his extensive work for major railway companies, particularly the Great Northern Railway and the Northern Pacific Railway. In an era before widespread color photography, paintings were vital marketing tools. Railways sought to lure tourists, settlers, and investors westward by showcasing the scenic beauty accessible via their lines. Fery became one of the most prolific artists employed in this capacity. His ability to capture the grandeur of the landscapes quickly and effectively made him highly sought after.

For the Great Northern Railway, under the ambitious direction of James J. Hill and later his son Louis W. Hill, Fery produced over 300 paintings. Louis Hill was a particularly enthusiastic promoter of Glacier National Park, which the Great Northern's line traversed. Fery's paintings of Glacier's stunning vistas – its lakes, mountains, and glaciers – were commissioned to adorn the railway's stations, ticket offices, travel agencies, and, significantly, the grand lodges being built within the park, such as the Glacier Park Lodge and Many Glacier Hotel. These large, impressive canvases became integral to the "See America First" campaign, encouraging Americans to explore their own country's natural wonders rather than traveling abroad.

Fery also undertook substantial commissions for the Northern Pacific Railway, reportedly creating over 350 paintings for them. These works likely depicted scenes along their routes, including areas like Yellowstone National Park. The sheer volume of work Fery produced for the railways is staggering. It required constant travel, sketching expeditions into often remote areas, and rapid execution in the studio to meet demand. This commercial relationship provided Fery with financial stability and widespread visibility, distributing his art across the country and embedding his vision of the West in the popular imagination. His work played a tangible role in promoting tourism and potentially bolstering support for the preservation of areas like Yellowstone and Glacier.

Artistic Style and Technique

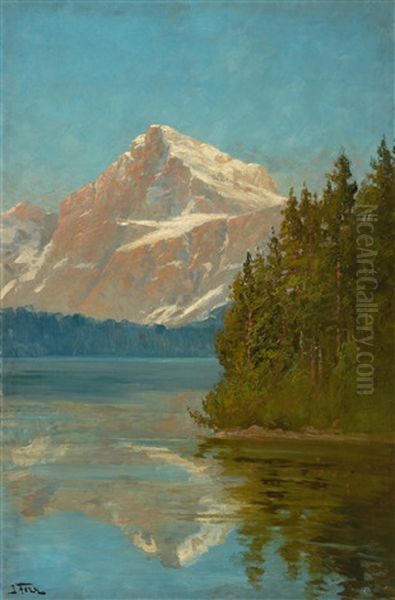

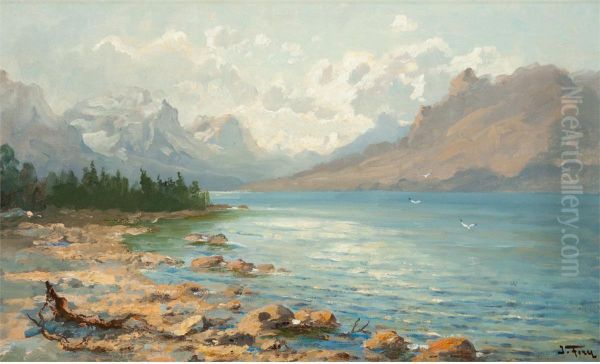

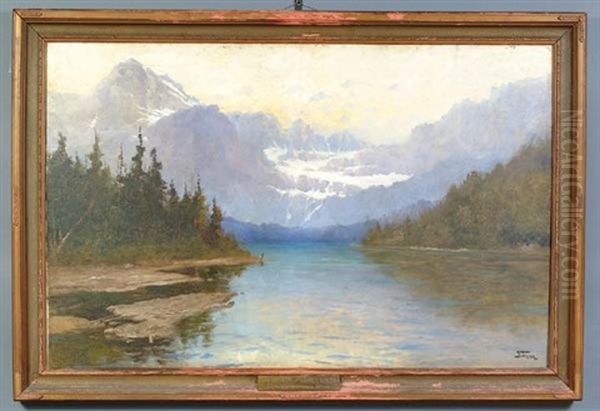

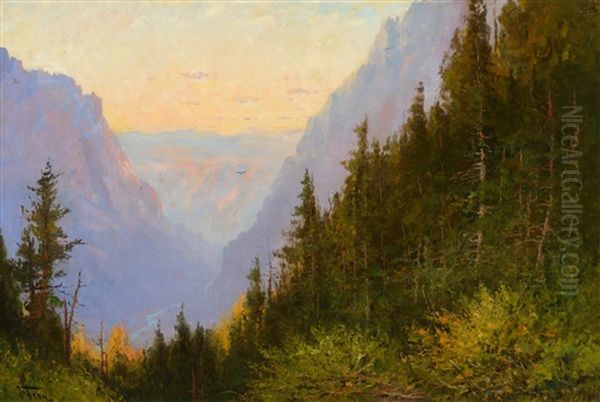

John Fery's style is often characterized as a form of Impressionism, but it's perhaps more accurately described as American Impressionism blended with elements of Realism and a touch of Romantic drama. While he adopted the Impressionist interest in capturing the effects of light and atmosphere, often using vibrant colors and visible brushwork, his work generally retained a stronger sense of structure and topographical accuracy than that of his French counterparts like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro. He was less concerned with deconstructing form through light and more focused on conveying the overall mood and majesty of the scene.

His technique was adapted to the demands of his commissions. He needed to work quickly and produce large canvases that made an immediate impact. This often led to a broad, energetic application of paint. He excelled at depicting the vastness of Western spaces, the dramatic play of sunlight and shadow on mountain faces, and the reflective qualities of water in alpine lakes. His colors could be intense, sometimes heightened for dramatic effect, capturing the clarity of mountain air or the fiery hues of a sunset over the Snake River. While some critics might point to a degree of formula in his compositions due to the sheer volume of his output, his best works possess a genuine power and sensitivity to the nuances of the landscape.

Fery likely relied on a combination of plein air sketching during his travels and studio work to complete the large commissioned pieces. The sketches would capture the immediate impressions of light and color, while the larger canvases allowed for more detailed rendering and compositional refinement. His ability to translate the monumental scale of the Rockies onto canvas, often working on paintings several feet wide, was remarkable. He conveyed not just the look, but the feel of these wild places – their solitude, their grandeur, their sometimes-intimidating beauty.

Iconic Subjects: Glacier, Yellowstone, and Beyond

While Fery painted landscapes across the American West and even other parts of the country, certain locations became synonymous with his name. Glacier National Park in Montana stands out as perhaps his most cherished and frequently depicted subject. His long association with the Great Northern Railway, the park's primary promoter, ensured a steady stream of commissions focused on this region. He painted iconic locations like Lake McDonald, St. Mary Lake, Lake Ellen Wilson, Grinnell Glacier, Swiftcurrent Lake, and Red Eagle Lake countless times, capturing them in different seasons and varying light conditions. His images helped define the visual identity of Glacier for generations of visitors.

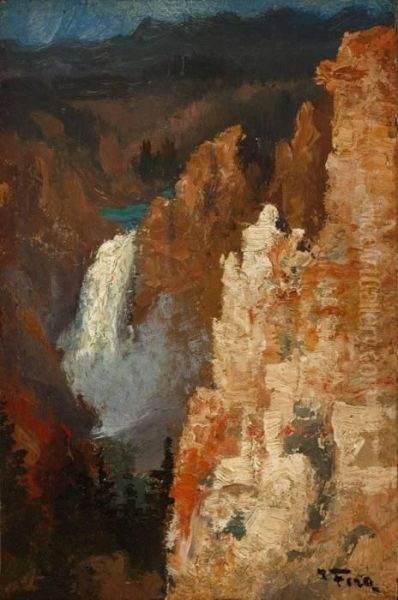

Yellowstone National Park was another crucial subject. His work for the Northern Pacific likely involved depicting Yellowstone's unique geothermal features, lakes, and canyons. Paintings like Cascade on the Firehole showcase his ability to render the dynamic interplay of water, rock, and forest characteristic of the park. His depictions of Yellowstone Lake contributed to its fame. Fery's paintings, alongside the photographs of William Henry Jackson and the earlier works of Thomas Moran, helped solidify Yellowstone's status as a national treasure and likely played a role in early tourism and conservation awareness.

Beyond these two iconic parks, Fery's brush captured other magnificent Western scenes. He painted extensively in the Teton Range of Wyoming, capturing the dramatic rise of the peaks above Jackson Lake and the winding course of the Snake River, as seen in works like Snake River Sunset. His travels also took him to the Canadian Rockies and potentially other areas of the American West. Wherever he went, his focus remained consistent: capturing the sublime power and beauty of mountainous landscapes, often emphasizing dramatic weather effects, reflections in water, and the vast scale of the wilderness.

Notable Works

Identifying a definitive list of John Fery's "most important" works is challenging given his prolific output and the fact that many paintings were commissions rather than pieces intended for gallery exhibition. However, several paintings are frequently cited or are representative of his major subjects and style:

Lake McDonald: Fery painted this iconic Glacier National Park lake numerous times. These works typically emphasize the lake's clear water, the surrounding forested slopes, and the dramatic backdrop of the mountains, often capturing stunning reflections and the play of light across the scene. Several versions adorned the walls of Great Northern Railway properties.

St. Mary Lake: Another jewel of Glacier, Fery captured its distinctive elongated shape and the dramatic peaks rising from its shores, including Going-to-the-Sun Mountain. His paintings often highlight the intense blue of the water and the ruggedness of the surrounding terrain.

Grinnell Glacier / Grinnell Lake: Depicting the park's glaciers was important, and Fery painted the Grinnell Glacier area, showcasing the ice, the turquoise meltwater lake below it, and the surrounding cirque. These works serve as historical records of the glacier's past extent.

Red Eagle Lake: This Glacier subject allowed Fery to explore compositions featuring prominent peaks reflected in the water, often with dramatic cloud formations.

Cascade on the Firehole: Representing his Yellowstone work, this painting captures the energy of the river and the textures of the surrounding rocks and foliage, demonstrating his skill beyond static mountain vistas.

Snake River Sunset: This title suggests a focus on atmospheric effects, likely featuring the Teton Range silhouetted against a vividly colored sky, reflected in the waters of the Snake River – a theme allowing for dramatic use of color and light.

Blue Lake: While the specific location might vary (there are many "Blue Lakes"), this title points to his recurring interest in capturing the intense, often deep blue hues characteristic of high-altitude alpine lakes.

These examples, alongside hundreds of others depicting similar scenes, collectively form the core of Fery's contribution. They are characterized by their scale, their often dramatic interpretation of light and landscape, and their connection to the promotion of the American West.

Fery in Context: Contemporaries and Influences

John Fery worked during a dynamic period in American art. The monumental landscape tradition established by Hudson River School painters and later Western explorers like Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran had set a precedent for depicting the grandeur of the American continent. While Fery's style differed, moving towards Impressionism, he inherited their interest in the sublime and the vastness of nature. Moran, in particular, shared Fery's connection to railway patronage (working for the Santa Fe Railway) and his focus on iconic Western parks like Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon.

In the broader context of American Impressionism, Fery's work stands somewhat apart. While contemporaries like Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, and J. Alden Weir were exploring Impressionist techniques, often focusing on more intimate landscapes, coastal scenes, or urban views primarily in the East, Fery applied Impressionist principles of light and color to the unique and monumental scale of the Rocky Mountains. His work was generally less experimental than that of the core American Impressionists, retaining a stronger commitment to representational accuracy demanded by his patrons.

Within the specific genre of Western art, Fery operated alongside artists focused on different themes. Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, arguably the most famous Western artists of the era, concentrated on narrative scenes of cowboys, Native Americans, and wildlife, capturing the human drama and mythology of the frontier. Fery's focus remained steadfastly on the landscape itself. Other artists also received railway commissions, such as Gustav Krollmann and Winold Reiss, who worked for the Great Northern, with Reiss becoming particularly known for his portraits of the Blackfeet people. Olaf Seltzer, a friend of Russell, also depicted Western scenes. Fery's niche was the prolific production of large-scale, scenic landscapes specifically for promotional purposes, a role he fulfilled perhaps more extensively than any other painter of his time. The photographer William Henry Jackson also played a crucial, parallel role in visually documenting and promoting the West, particularly Yellowstone.

Exhibitions, Collections, and Legacy

Despite the vast number of paintings John Fery created, his work was primarily disseminated through his railway patrons rather than traditional gallery exhibitions, especially during the peak of his career. The paintings were displayed in public and semi-public spaces – railway stations, hotels, lodges, offices – reaching a wide audience outside the typical art world circles. The Great Northern and Northern Pacific railways were, in effect, his primary collectors and exhibitors.

Significant collections of his work remain associated with these origins. The Glacier Park Lodge in East Glacier, Montana, still displays several large Fery canvases commissioned for the hotel, offering visitors a glimpse into the original ambiance intended by Louis Hill. Institutions dedicated to Western art or regional history also hold his works. The Hockaday Museum of Art in Kalispell, Montana, near Glacier National Park, has featured his work prominently, including a major centennial exhibition in 2010 titled "John Fery: Artist of the Rockies." The Wildling Museum in California holds Cascade on the Firehole.

Many of Fery's paintings passed into private hands over the decades, sometimes dispersed when railway collections were reduced or properties changed ownership. His works appear regularly at auctions specializing in Western American art, such as the C.M. Russell Art Auction, often commanding significant prices, indicating a continued appreciation among collectors. While perhaps not always granted the same critical acclaim as some of his contemporaries during his lifetime, recent decades have seen a renewed interest in Fery's work, recognizing his skill, his historical importance in promoting the West, and the sheer aesthetic appeal of his dramatic landscapes. His legacy is tied not just to art history, but to the history of tourism, conservation, and the cultural iconography of the American West.

The Man Behind the Canvas

Compared to the vast visual legacy he left behind, detailed records of John Fery's personal life and personality are relatively scarce. He appears to have been intensely focused on his work, driven by the demands of his commissions and perhaps a personal passion for the landscapes he painted. The summary notes mention that some biographical details, like the birth record of a daughter, remain elusive, adding a slight air of mystery. This lack of abundant personal anecdotes or writings leaves his paintings as the primary testament to his experiences and perspective.

His life story embodies elements of the immigrant experience – leaving Europe to find success and a unique niche in America. His Hungarian or Austrian origins connected him to a rich European cultural heritage, which he then adapted to the very different environment of the American West. The sheer volume of his output suggests tremendous energy and dedication. Traveling through rugged mountain terrain, often under challenging conditions, to sketch and gather material required physical stamina and determination.

While direct records of his interactions with other prominent artists are limited, his close working relationship with railway executives like Louis W. Hill is well-documented. This suggests an ability to navigate the world of commercial patronage effectively. He was, in essence, a professional artist who found a way to align his talents with the expansive commercial and cultural forces shaping the American West at the turn of the twentieth century. The "mystery" surrounding him may simply be the result of a life lived more through the act of painting than through public pronouncements or recorded personal dramas.

Conclusion: Chronicler of Western Majesty

John Fery occupies a unique and important place in the history of American art. As a prolific painter of the American West, particularly the Rocky Mountains of Glacier and Yellowstone, he created an enduring visual record of these magnificent landscapes during a key period of their introduction to the broader American public. His distinctive style, blending Impressionistic attention to light and atmosphere with a dramatic, often idealized, realism, proved perfectly suited to the promotional needs of the railway companies that were his primary patrons. Through hundreds of canvases displayed across the nation, Fery helped shape the popular image of the West as a land of sublime beauty and natural wonder, contributing significantly to the "See America First" movement and the growth of tourism.

While operating somewhat outside the mainstream art establishment of his time, Fery's dedication to his craft and his ability to capture the grandeur of his chosen subjects earned him lasting recognition. His paintings are more than just topographical records; they convey an emotional response to the power and majesty of the wilderness. Today, his works are sought after by collectors and appreciated by museum visitors, serving as both historical documents and compelling artistic statements. John Fery remains a key figure for understanding how the American West was seen, imagined, and promoted at the dawn of the twentieth century, a true chronicler of its enduring grandeur.