Thomas Frye (circa 1710–1762) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 18th-century British art. An artist of diverse talents, he was not only a painter of considerable skill, particularly in portraiture, but also a pioneering mezzotint engraver and a key figure in the early development of English porcelain. His life and career, though relatively short and plagued by ill health, left an indelible mark on the artistic and manufacturing scenes of Georgian England. Navigating the vibrant, competitive art world of London, Frye carved out a unique niche, demonstrating innovation and a distinctive artistic vision.

Early Life and Emergence in London

Born near Dublin, Ireland, around 1710, Thomas Frye's early years and artistic training remain somewhat obscure, a commonality for many artists of his era before the formal establishment of art academies and comprehensive record-keeping. It is presumed he received his initial artistic education in Dublin, a city with a burgeoning, albeit smaller, artistic community compared to London. By the early 1730s, Frye had made the pivotal move to London, the gravitational center of artistic patronage and opportunity in Britain. This was a period when the arts in Britain were beginning to flourish, moving out of the shadow of continental dominance, with native-born and immigrant artists alike contributing to a burgeoning national school.

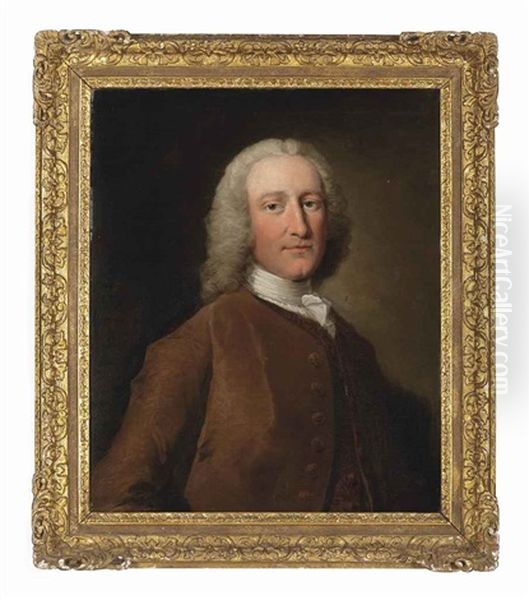

Upon his arrival in London, Frye began to establish himself as a portrait painter. Portraiture was the most lucrative and sought-after genre, patronized by a wealthy aristocracy and an increasingly affluent merchant class eager to have their likenesses immortalized. Frye worked in both oils and pastels, a medium gaining popularity for its soft textures and vibrant colours, championed by artists like the Swiss Jean-Étienne Liotard, who would later visit London to great acclaim. Frye's early portraits, while perhaps not possessing the flamboyant grandeur of some of his contemporaries, were noted for their competent likeness and sensitive handling.

One of his most recognized works from this period, and indeed one that has helped secure his name, is the portrait of Augusta, Princess of Wales, often referred to by titles such as "The Duchess of Brunswick" due to dynastic connections (though primarily known as Princess of Wales). Augusta, the mother of the future King George III, was a significant patron of the arts, and a commission from such a high-profile figure would have been a considerable boost to Frye's reputation. This portrait, likely painted in the 1740s, showcases his ability to capture a sense of dignified presence, a hallmark of royal portraiture.

The Bow Porcelain Venture

Beyond his work as a painter, Thomas Frye embarked on a remarkable and demanding venture in the mid-1740s that would significantly impact the course of English ceramic history. He became a partner and manager of the newly established Bow porcelain factory in East London, also known as "New Canton." Alongside his fellow patentee, Edward Heylyn, Frye was instrumental in developing a commercially viable soft-paste porcelain formula. This was a period of intense experimentation across Europe, as manufacturers sought to replicate the coveted hard-paste porcelain imported from China.

Frye's contribution was not merely managerial; his artistic skills were likely employed in the design and decoration of the early Bow wares. The factory aimed to produce porcelain that could compete with imports and with wares from other emerging European factories like Meissen or Sèvres. The Bow formula notably incorporated bone ash, a key ingredient that would become characteristic of English bone china. This innovation made the porcelain stronger and whiter. Under Frye's guidance, the Bow factory produced a wide range of items, from utilitarian tableware to more ambitious figures and ornamental pieces, often reflecting the prevailing Rococo taste with its asymmetrical designs, scrollwork, and naturalistic motifs.

The demands of managing the Bow factory, with its technical challenges, financial pressures, and the noxious fumes from the kilns, took a severe toll on Frye's health. After nearly fifteen years dedicated to the porcelain enterprise, suffering from lung complaints (likely consumption, exacerbated by the factory environment), he was forced to retire from Bow around 1759 to recuperate. This period, though draining, demonstrated Frye's versatility and entrepreneurial spirit, placing him at the forefront of a significant industrial and artistic development in Britain. His work at Bow helped lay the foundation for the English porcelain industry, which would see figures like Josiah Wedgwood later rise to international prominence.

Return to Art: The Mezzotint Masterpieces

After a period of convalescence in Wales, Thomas Frye returned to London and to his artistic pursuits, but with a renewed focus, primarily on the medium of mezzotint. Mezzotint, a tonal engraving process, was exceptionally well-suited for reproducing the subtle gradations of light and shadow found in oil paintings, making it popular for disseminating portraits. Frye, however, approached mezzotint not merely as a reproductive medium but as a primary form of artistic expression.

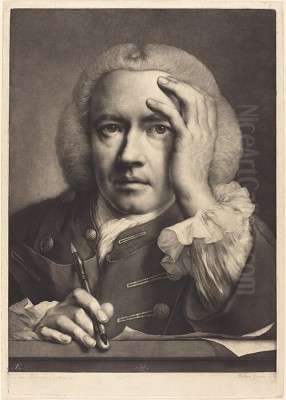

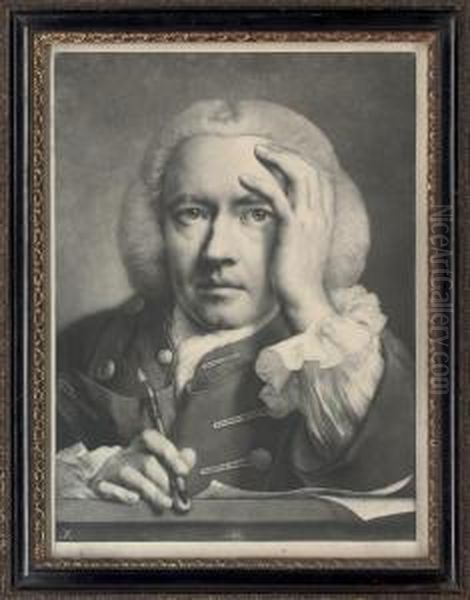

Between 1760 and his death in 1762, Frye produced a series of remarkable, life-sized portrait heads in mezzotint, often referred to as his "Fancy Heads" or "Life-Sized Heads." These were not commissioned portraits of specific individuals but rather character studies, often depicting figures in exotic or theatrical attire, imbued with a dramatic and sometimes melancholic sensibility. Works such as "An Old Man," "A Young Woman with a Turban," or his own striking self-portraits in this medium, showcase his extraordinary command of mezzotint. He achieved rich, velvety blacks and delicate highlights, creating images of compelling psychological intensity and presence.

These large-scale mezzotints were innovative and ambitious. They pushed the boundaries of the medium and were highly admired for their technical brilliance and artistic power. Frye's handling of light, often creating a strong chiaroscuro effect, lent his figures a sculptural quality. These works resonated with a public increasingly interested in sensibility and the expression of emotion, themes gaining traction in the latter half of the 18th century. His pupils, including William Pether and James McArdell (though McArdell was more a contemporary and fellow Irishman who became a leading mezzotinter), helped to carry forward the high standards of British mezzotint engraving. Frye's mezzotints stand alongside the best work of other prominent engravers of the era, such as John Faber Jr., Richard Houston, and later Valentine Green.

Artistic Style and Influences

Thomas Frye's artistic style evolved throughout his career, shaped by his diverse activities and the prevailing tastes of his time. As a portrait painter, his early work shows the influence of established London portraitists like Jonathan Richardson and, to some extent, the enduring legacy of Sir Godfrey Kneller, who had dominated British portraiture in the preceding generation. Frye's approach was generally more direct and less flamboyant than some of his contemporaries who were embracing the lighter, more decorative Rococo style. However, a certain elegance and sensitivity are apparent, particularly in his female portraits.

His work in pastels allowed for a softness and immediacy, and he was adept at capturing textures and expressions in this medium. When compared to the giants of mid-18th century British portraiture – the incisive social commentary of William Hogarth, the burgeoning grandeur of Joshua Reynolds, the lyrical elegance of Thomas Gainsborough, or the refined naturalism of Allan Ramsay – Frye's painted portraits hold a more modest but still respectable place. He was a competent and sensitive observer, capable of producing pleasing and characterful likenesses.

It is in his mezzotints, however, that Frye's most distinctive artistic voice emerges. Here, he moved beyond straightforward representation to explore mood, character, and dramatic effect. The "Life-Sized Heads" are powerful and imaginative, demonstrating a romantic sensibility that prefigures later trends. His mastery of chiaroscuro in these prints is exceptional, creating a sense of volume and atmosphere that is deeply compelling. These works suggest an artist exploring the expressive potential of his medium to its fullest, less constrained by the demands of patronage that often dictated the content and style of painted portraits.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Thomas Frye operated within a dynamic and competitive London art world. The mid-18th century was a transformative period for British art. Artists like William Hogarth were championing a distinctly British modern moral subject, while portraitists like Thomas Hudson (Reynolds's master) maintained a solid, if somewhat conventional, practice. The arrival of foreign artists like Canaletto, who painted Venetian-inspired views of London, and Jean-Étienne Liotard, with his exquisite pastels, added to the cosmopolitan flavour of the scene.

The Society of Artists of Great Britain, of which Frye was an early member, was established in 1761, providing a public venue for artists to exhibit their work, a precursor to the Royal Academy of Arts (founded in 1768, after Frye's death). This period saw a growing professionalization of the artist's role and an increasing public appetite for art. Frye's mezzotints, being prints, were more accessible to a wider audience than unique oil paintings, contributing to the dissemination of artistic imagery.

His influence can be seen in the work of mezzotint engravers who followed, benefiting from his technical innovations and the heightened status he brought to the medium as a creative art form. While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as Reynolds or Gainsborough in painting, his contributions to mezzotint and porcelain were highly significant and recognized by his peers.

Later Years and Legacy

The intense labour involved in producing his series of large mezzotints, coupled with his pre-existing health problems, likely hastened Thomas Frye's decline. He died on April 2, 1762, in London, at a relatively young age, around 52. His death cut short a career that had shown remarkable resurgence and innovation in its final years. He was buried at Hornsey Churchyard.

Thomas Frye's legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he produced a body of competent and often sensitive portraits, including the significant likeness of Augusta, Princess of Wales. As a co-founder and manager of the Bow porcelain factory, he played a crucial role in the birth of the English porcelain industry, contributing to both its technical and artistic development. His most unique and enduring artistic achievement, however, lies in his powerful and innovative mezzotints. These "Life-Sized Heads" are considered masterpieces of the medium, admired for their technical virtuosity, their psychological depth, and their dramatic intensity.

Though his name might not be as widely recognized today as some of his more famous contemporaries, Thomas Frye's contributions were substantial. He navigated different artistic and industrial fields with skill and vision, leaving a distinct mark on 18th-century British art and manufacturing. His work is represented in major collections, including the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, ensuring that his artistic achievements continue to be appreciated.

Clarifying Confusions: Other Individuals and Misattributions

It is important, in discussing Thomas Frye the artist (1710-1762), to acknowledge that the name, or variations of it, may appear in different contexts, leading to potential confusion. The information provided in the initial query for this article contained several such instances, which require careful separation from the biography of the 18th-century painter and engraver.

For instance, references to a "Thomas Frye" as an "American postmodern architect" with an interest in "Oriental charm," "natural characteristics of materials," "harmony with nature," and "sustainability" clearly point to a different individual, likely a contemporary architect, whose work and philosophy are distinct from the 18th-century artist. Similarly, mentions of a "Tom Fry" as a "multidisciplinary artist" working with "digital, physical art, written expression" and inspired by "Cubism, Expressionism, Existentialism, street art, and Neo-Expressionism" also describe a modern or contemporary artist, not the historical figure who died in 1762.

Furthermore, discussions around a "Thomas Frye" exploring "literary and artistic connections" through "musical concepts (circle of fifths)" and "formal exploration" bear a striking resemblance to the interests and work of Northrop Frye (1912-1991), a highly influential Canadian literary critic and theorist. Northrop Frye's seminal work, "Anatomy of Criticism," and his extensive writings on literature, myth, and culture, place him firmly in the 20th century and in a field entirely separate from the 18th-century visual artist Thomas Frye. The historical evaluation and artistic influence attributed to "Northrop Frye" in the source material – such as being a "pioneer of literary criticism," his impact on "American literary criticism," and his engagement with "political, cultural, and artistic" matters from the Great Depression to the Reagan era – unequivocally pertain to the literary critic, not the painter.

Finally, an anecdote concerning a "Claude Frye," described as an elderly man in Florida facing eviction and hardship, is an entirely unrelated story. While poignant, it has no bearing on the life or work of Thomas Frye, the 18th-century artist. Such conflations can occur due to similarities in names or the way information is aggregated in search results, but it is crucial for historical accuracy to distinguish between these separate individuals and their respective stories. The focus of this account remains steadfastly on Thomas Frye, the Irish-born painter, mezzotinter, and porcelain pioneer active in 18th-century London.

Enduring Significance

In conclusion, Thomas Frye of Dublin and London was an artist of remarkable versatility and quiet innovation. His journey from a young Irish painter seeking fortune in London to a key figure in the nascent English porcelain industry, and finally to a master of the mezzotint, speaks to a restless creativity and a determination to make his mark. While the grand narratives of art history often focus on the titans of painting like Reynolds or Gainsborough, figures like Frye provide crucial depth and texture to our understanding of the period. His portraits offer valuable records of his sitters, his work at Bow was foundational for a major British industry, and his mezzotints remain a powerful testament to his artistic vision and technical prowess. Thomas Frye's contributions, though perhaps less universally celebrated, are integral to the rich tapestry of 18th-century British art.