Thomas Girtin stands as a pivotal figure in the history of British art, particularly celebrated for his revolutionary approach to watercolour painting during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Born in the London borough of Southwark on February 18, 1775, his tragically short life, ending on November 9, 1802, belied the profound impact he would have on the trajectory of landscape art in Britain. An accomplished painter and etcher, Girtin was instrumental in elevating watercolour from a medium primarily used for topographical records to a respected, independent art form capable of great expressive power and romantic sensibility. His close association, marked by both friendship and rivalry, with his contemporary J.M.W. Turner, further highlights his significance in a transformative era for British art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Thomas Girtin's origins trace back to Southwark, London. His father, a brush manufacturer of Huguenot descent, passed away when Girtin was young. Subsequently, his mother married Mr. Vaughan, a man described as a pattern-draughtsman, potentially providing an early exposure to artistic or technical drawing within the household. From a young age, Girtin demonstrated an aptitude for drawing and pursued formal training.

His formative artistic education involved an apprenticeship under Edward Dayes, a notable topographical watercolourist and engraver. This training grounded Girtin in the precise techniques of topographical depiction, which emphasized accuracy in rendering landscapes and architecture. This tradition, also exemplified by artists like Paul Sandby, often involved detailed drawing overlaid with transparent washes, frequently starting with a monochrome underpainting in grey wash. While Girtin mastered these skills, his artistic vision soon pushed beyond the purely descriptive aims of topography.

The Monro Circle and Partnership with Turner

A crucial phase in Girtin's development occurred during his association with Dr. Thomas Monro, a physician and avid art collector and patron. In the evenings, at Dr. Monro's home in Adelphi Terrace, Girtin and another young, exceptionally talented artist, Joseph Mallord William Turner, were employed to copy and colour prints and drawings from Monro's collection. This informal 'Monro Academy' provided invaluable experience and exposure to the works of earlier masters.

Among the artists whose work they studied and copied were the landscape watercolourists John Robert Cozens and possibly Alexander Cozens. This exercise allowed both Girtin and Turner to absorb different approaches to landscape composition, light, and atmosphere, while simultaneously developing their own distinct styles. The Monro circle also included other emerging talents, such as John Sell Cotman, fostering an environment of learning and artistic exchange.

The relationship between Girtin and Turner during this period was complex and deeply influential for both. Born in the same year, they were initially friends and collaborators, learning side-by-side. However, their immense talents inevitably led to a degree of rivalry. Turner famously acknowledged Girtin's exceptional ability, reportedly stating later in life, "If Tom Girtin had lived, I should have starved." This remark underscores the immense respect Turner held for Girtin's talent and the potential trajectory his career might have taken had he not died so young.

Artistic Style and Technical Innovation

Thomas Girtin's artistic style underwent a significant evolution during his brief career. Moving beyond the constraints of his topographical training under Dayes, he developed a bolder, more expressive, and distinctly Romantic approach to landscape painting. His work became characterized by a breadth of vision, a sensitivity to atmospheric effects, and a powerful use of colour.

One of Girtin's most significant contributions was his departure from the traditional method of watercolour painting, which relied heavily on detailed pencil outlines filled in with transparent washes, often built upon a neutral grey underpainting (the 'grey wash' technique). Girtin increasingly abandoned this meticulous process in favour of laying down broad areas of strong, resonant colour directly onto the paper. This allowed for greater spontaneity and a more unified, atmospheric effect.

He pioneered a new and richer watercolour palette, moving away from pale tints towards deeper, more evocative tones. His characteristic colours included warm browns, resonant slate greys and blues, and rich indigos. These colours were used not just to describe form but to convey mood, weather, and the specific quality of light. His handling of light and shadow became increasingly sophisticated, contributing to the dramatic and poetic quality of his landscapes.

While embracing a more Romantic vision, Girtin retained his exceptional skill in depicting architecture and topography, learned during his apprenticeship. His drawings and watercolours of buildings, whether grand cathedrals or humble structures, demonstrate a remarkable understanding of form, structure, and perspective, integrated seamlessly within their landscape settings. This combination of architectural accuracy and atmospheric breadth became a hallmark of his mature style. His work showed a naturalism combined with a Romantic spirit, capturing both the specific details and the emotional essence of a place.

Major Works and Achievements

Despite his short career, Thomas Girtin produced a remarkable body of work, including several pieces now considered masterpieces of British watercolour painting. His subjects ranged from the landscapes of Northern England and Wales to views of London and Paris.

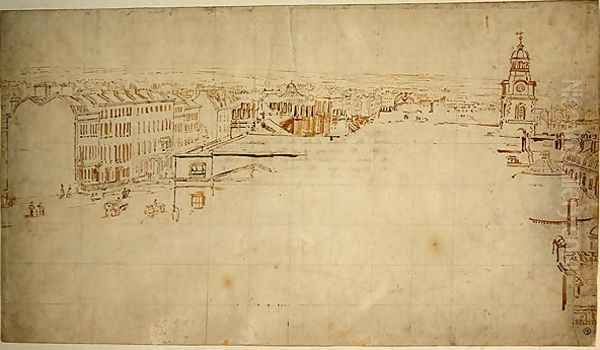

Among his most celebrated achievements was the Eidometropolis, a vast, 360-degree panorama of London painted in oil, exhibited in 1802. Although the original painting is now lost, preparatory sketches and related watercolours survive, showcasing his ambition and his ability to handle large-scale compositions depicting the sprawling cityscape. This project demonstrated his mastery of perspective and his keen observation of urban life and atmosphere.

The White House, Chelsea (c. 1800) is often cited as a pinnacle of his watercolour technique. This seemingly simple scene is rendered with extraordinary subtlety and breadth, capturing the tranquil light and atmosphere of the Thames riverside with broad washes of luminous colour. It exemplifies his move away from linear detail towards suggestive forms and tonal harmony.

His skill in architectural subjects is evident in works like St. Paul's Cathedral (c. 1795), an early but accomplished view demonstrating his precise draughtsmanship, and Ely Cathedral (exhibited 1795), one of his first exhibited independent works, based on a sketch by the antiquarian James Moore. This early work already hinted at his developing interest in landscape and atmospheric effects.

Girtin's travels through Britain provided subjects for some of his most powerful landscapes. Durham Cathedral and Castle (c. 1797-98) is a majestic composition, perfectly balancing the imposing architecture with the surrounding natural landscape under a dramatic sky. It showcases his ability to convey grandeur and a sense of place through bold composition and rich colouring. Similarly, works like Caernarvon Castle and Morpeth Bridge demonstrate his unique understanding of light, space, and structure within a landscape context.

Later in his career, during a trip to France, he produced a series of views, including etchings and watercolours like Rue Saint-Denis, Paris. These works capture the character of the French capital with the same sensitivity to architecture and atmosphere found in his British subjects. Works like Canal at Venice, likely based on sketches by others, show his ability to evoke the unique light and colour of different locales. Other notable works include Great Yarmouth: The South Gate (c. 1795-96) and Lindisfarne Castle (c. 1796-97), further demonstrating his mastery of coastal and architectural scenes early in his independent career.

Travels, Health, and Untimely Death

In the later years of his short life, Girtin's health began to decline significantly. Sources vary on the exact nature of his illness, citing both asthma and tuberculosis (consumption) as potential causes. Seeking perhaps a change of climate or simply continuing his artistic pursuits, he travelled to Paris in late 1801 or early 1802, remaining there for several months.

During his time in France, despite his failing health, Girtin continued to work, producing a series of sketches and watercolours of Paris. He also created a set of soft-ground etchings, Twenty Views in Paris and its Environs, which were published posthumously. This period abroad highlights his dedication to his art even in the face of severe physical challenges.

Upon returning to London, his condition worsened. Thomas Girtin died in his painting room on November 9, 1802, at the age of just 27. His premature death was a significant loss to the British art world, cutting short a career of extraordinary promise and already remarkable achievement. His passing was deeply felt by his contemporaries, including Turner, who recognized the unique talent that had been extinguished.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Thomas Girtin's legacy far outweighs the brevity of his life. He played a crucial role in transforming the status and style of watercolour painting in Britain. By moving beyond the purely descriptive function of topography and embracing a more personal, expressive, and Romantic approach, he demonstrated the medium's potential for serious artistic statement. His technical innovations, particularly his use of broad washes and a richer colour palette, fundamentally changed watercolour practice.

His influence on his contemporaries, most notably J.M.W. Turner, was profound. While Turner's career would ultimately reach unparalleled heights, his early development was significantly shaped by his association with Girtin. Girtin's emphasis on atmospheric effects, bold compositions, and the emotional resonance of landscape provided a foundation upon which Turner, and others, would build. Turner's later assessment of Girtin's importance speaks volumes about this influence.

Girtin's vision of landscape, characterized by what has been described as "romantic open spaces" and a "truthful capture of natural detail," resonated through nineteenth-century British landscape painting. While perhaps not a direct precursor in the same way as John Constable, Girtin's focus on light, atmosphere, and the poetic interpretation of nature certainly contributed to the climate in which later movements, including potentially aspects prefiguring Impressionism's concern with transient effects, could emerge. His work built upon the foundations laid by earlier landscape artists like Richard Wilson, while paving the way for subsequent generations of watercolourists such as David Cox and Peter De Wint.

He helped establish watercolour as a major British art form, celebrated for its luminosity and immediacy. His ability to combine topographical accuracy with romantic feeling created a powerful new mode of landscape representation.

Collections and Recognition

Today, Thomas Girtin's works are held in major public collections around the world, affirming his status as a key figure in British art history. Significant holdings can be found in the British Museum, Tate Britain, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Other important collections include the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge (holding works like Great Yarmouth: The South Gate), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (holding Lindisfarne Castle).

His life and work have been the subject of continued scholarly interest and major exhibitions. A landmark exhibition, "Thomas Girtin: The Art of Watercolour," was held at Tate Britain in 2002, marking the bicentenary of his death. This exhibition brought together around 200 works and provided a comprehensive overview of his techniques, artistic development, and influence. Other exhibitions featuring his work include "British Watercolours and Drawings 1750-1950" at the Wichita Museum of Art (1983) and displays at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (e.g., 2007).

Numerous publications have explored his art, including the catalogue accompanying the 2002 Tate exhibition, edited by Greg Smith, and earlier studies such as The Art of Thomas Girtin by Thomas Girtin (his grandson) and David Loshak (1954). These resources, along with catalogues like British Watercolours and Drawings (1986), document his oeuvre and critical reception.

Thomas Girtin remains celebrated as a master of watercolour, an innovator whose bold techniques and romantic vision significantly advanced British landscape painting. His tragically short life left behind a legacy of breathtakingly beautiful and influential works, securing his place as one of the founders of the great English watercolour tradition.