Walt Kuhn stands as a significant, albeit complex, figure in the narrative of American modern art. Born in the late 19th century, his career spanned a transformative period in artistic expression, both in Europe and the United States. Kuhn was not merely a painter; he was a multifaceted artist encompassing roles as a cartoonist, sculptor, printmaker, designer, teacher, and, perhaps most crucially, a pivotal organizer and promoter of modern art. His legacy is indelibly linked to the groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show, an event he was instrumental in realizing, which irrevocably altered the course of American art history. Simultaneously, his own artistic output, particularly his powerful and empathetic portraits of performers, carved a distinct niche for him, blending modernist sensibilities with a deeply felt humanism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

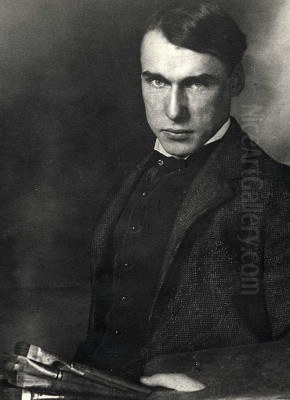

Walter Francis Kuhn entered the world on October 27, 1877, in Brooklyn, New York, a city rapidly evolving into a global metropolis. His early years were marked by an emerging interest in the visual arts, leading him to pursue formal studies. In 1893, he enrolled at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, seeking foundational training. However, like many aspiring American artists of his generation, Kuhn felt the pull of broader horizons and practical experience.

Seeking adventure and professional opportunities, Kuhn traveled west to California in 1899. Settling in San Francisco, he found work as a cartoonist and illustrator for the magazine The Wasp. This period honed his skills in draftsmanship and visual storytelling, providing a practical counterpoint to more academic training. The experience as a cartoonist likely influenced his later painting style, contributing to the bold lines and directness that characterize much of his mature work. Yet, the lure of the European art capitals, the epicenters of avant-garde innovation, remained strong.

European Sojourn and Formative Influences

In 1901, Kuhn embarked on the quintessential journey for ambitious artists of his time: a trip to Europe to immerse himself in its rich artistic traditions and burgeoning modern movements. His first stop was Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world. There, he studied at the Académie Colarossi, a liberal institution known for welcoming foreign students and offering less rigid instruction than the official École des Beaux-Arts. Paris exposed him to the legacy of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, the radical color experiments of the Fauves like Henri Matisse and André Derain, and the nascent stirrings of Cubism being developed by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque.

Seeking different perspectives, Kuhn then traveled to Munich in 1902, enrolling in the Royal Academy (Akademie der Bildenden Künste). Germany offered exposure to its own powerful strains of modernism, including the Jugendstil movement and the burgeoning German Expressionism, with artists like Wassily Kandinsky beginning to push towards abstraction and groups like Die Brücke (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, etc.) exploring raw emotional intensity. This European sojourn was crucial, equipping Kuhn not only with technical skills but also with a firsthand understanding of the revolutionary changes sweeping through contemporary art. He absorbed the lessons of masters like Paul Cézanne, whose emphasis on structure would resonate in Kuhn's later still lifes, and saw the expressive power unleashed by artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin.

Return to New York and Early Career

Returning to New York City in 1903, Kuhn was armed with European training and a broadened artistic perspective. He settled in Manhattan and resumed his career, initially focusing again on illustration to support himself. He contributed cartoons and drawings to popular publications such as Life, Puck, Judge, and the New York World. This work kept him connected to the city's vibrant cultural life and further sharpened his observational skills and ability to capture character succinctly.

While commercial illustration provided income, Kuhn harbored ambitions as a serious painter. In 1905, he had his first significant solo exhibition at the Salmagundi Club in New York. This event helped establish his reputation beyond illustration, showcasing his talents as both a cartoonist and a painter aiming for fine art recognition. During these years, he navigated the New York art scene, exhibiting his work and gradually developing his personal style, still absorbing the influences he encountered abroad while grounding his work in American subjects and sensibilities. He became increasingly aware of the conservative nature of the established art institutions in the US.

The Genesis of the Armory Show

The early 1910s marked a turning point in Kuhn's career, shifting his focus towards collective action and the promotion of modern art. Dissatisfaction was growing among progressive American artists regarding the conservative exhibition policies of the dominant National Academy of Design. Kuhn, along with fellow artists like Jerome Myers, Elmer MacRae, and the painter Arthur B. Davies, became central figures in the formation of a new organization: the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), formally established in 1911.

Kuhn served as the energetic secretary of the AAPS. The group's primary goal was ambitious: to organize a large-scale, independent exhibition that would showcase the most advanced trends in both American and European art, bypassing the traditional jury systems. This vision culminated in the plan for what would become the International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show. Kuhn's organizational skills, tenacity, and growing network were indispensable to this endeavor.

In the summer and fall of 1912, Kuhn, alongside AAPS president Arthur B. Davies and later joined by artist Walter Pach, embarked on a whirlwind tour of Europe. Their mission was to select cutting-edge European works for the upcoming exhibition. They visited studios, galleries, and collectors in London, Paris, The Hague, Amsterdam, Munich, and Berlin. They secured loans of works by established modern masters and daring new talents, including Constantin Brancusi, Marcel Duchamp, Odilon Redon, Francis Picabia, as well as key figures of Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism. Kuhn's enthusiasm and persuasive abilities were crucial in convincing European artists and dealers to participate in this unprecedented American venture.

The Armory Show of 1913: A Cultural Watershed

The International Exhibition of Modern Art opened on February 17, 1913, at the 69th Regiment Armory on Lexington Avenue in New York City. It was an event of monumental significance. Featuring around 1,300 works by over 300 artists, roughly one-third European and two-thirds American, the Armory Show provided the American public and artists with their first comprehensive look at the European avant-garde. Styles like Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism, previously known only to a few, were suddenly thrust into the spotlight.

The exhibition generated immense public interest, drawing huge crowds, but also provoked outrage, ridicule, and fierce debate in the press and among traditionalist critics. Works like Marcel Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 became symbols of the perceived incomprehensibility and radicalism of the new art. Despite the controversy, or perhaps partly because of it, the Armory Show was a succès de scandale. It traveled in reduced form to Chicago and Boston, spreading its influence further.

Walt Kuhn's role as the primary organizer and tireless promoter was undeniable. He handled logistics, publicity, and endless administrative tasks. The Armory Show fundamentally shifted the American art landscape. It challenged academic conventions, stimulated American artists like Stuart Davis and Charles Sheeler to engage with modernism, fostered the growth of modern art collecting (patrons like John Quinn and Lillie P. Bliss were significantly influenced), and paved the way for new galleries and museums dedicated to contemporary art, including the eventual founding of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. For Kuhn, it was a triumph of organization but also marked the beginning of a gradual withdrawal from large-scale promotional activities to focus more intensely on his own painting.

Post-Armory Show and Shifting Focus

In the years immediately following the Armory Show, Kuhn remained active in artist circles. He was involved with groups like the Kit Kat Club and was a founder of the Penguin Club in 1917, which provided studio space and exhibition opportunities for artists. These clubs fostered camaraderie and intellectual exchange among New York's progressive artists. He continued to paint and exhibit, but the immense effort of the Armory Show had taken a toll.

Gradually, particularly from the late 1910s and into the 1920s, Kuhn began to concentrate more fully on his personal artistic development. While he had always painted, this period saw him refine his style and subject matter, moving towards the themes and approach that would define his mature work. The experience of the Armory Show, exposing him intimately to the breadth of modern art, undoubtedly informed his own evolving aesthetic, pushing him towards greater simplification of form and bolder use of color.

The World of the Performer: Kuhn's Signature Subject

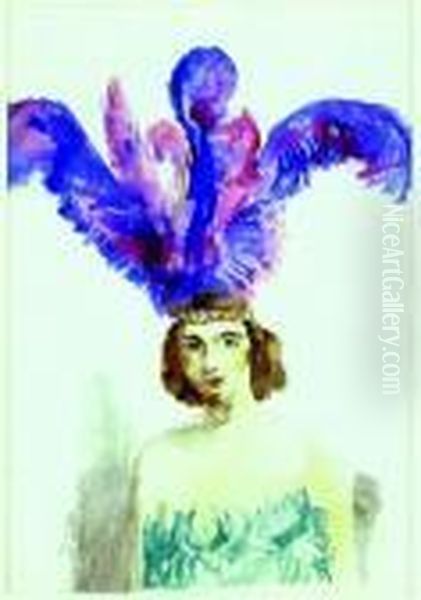

The 1920s witnessed Kuhn's definitive turn towards the subject matter for which he is best known: portraits of circus performers, vaudeville actors, clowns, acrobats, and showgirls. He developed a deep fascination with these figures, seeing them not just as entertainers but as individuals embodying resilience, professionalism, and often, a poignant sense of isolation behind their public personas. He spent considerable time backstage, observing and sketching, forming relationships with the performers he depicted.

His portraits from this era are characterized by their directness, psychological intensity, and formal rigor. Works like The White Clown (c. 1929) and Trio (1937) showcase his signature style: strong, dark outlines defining simplified, almost monumental forms, set against stark, often unadorned backgrounds. He used color boldly and expressively, not merely for description but to convey mood and character. His clowns are rarely just figures of fun; they often possess a gravitas, a world-weariness, or an enigmatic quality that invites deeper contemplation. Figures like the stoic acrobat in Acrobat in Red and Green (1942) or the introspective subject of Chico with a Top Hat (1948) reveal Kuhn's empathy and his interest in the human condition beneath the greasepaint and costumes.

Kuhn’s approach differed from artists like Edgar Degas or Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who also depicted performers. While they captured the movement and atmosphere of the performance world, Kuhn focused more on the static, confrontational portrait, emphasizing the performer as an archetype, often imbued with a sense of dignity and inner strength, yet hinting at vulnerability. His figures possess a sculptural quality, a solidity achieved through simplified planes and strong contours, reflecting perhaps the lingering influence of Cézanne and the formal concerns of modernism. These performer portraits became his most celebrated and enduring contribution to American art.

Exploring Still Life and Landscape

While best known for his performer portraits, Kuhn also worked consistently in other genres, notably still life and landscape. His still lifes, particularly those featuring apples, directly engage with the legacy of Paul Cézanne. Works like Green Apples and Scoop (1939) demonstrate Kuhn's interest in structure, volume, and the relationships between objects. He employed strong outlines and focused on the essential forms, using color to build volume and create a sense of tangible presence. Though sometimes criticized by contemporaries for lacking the profound spatial investigations of Cézanne, these works reveal Kuhn's commitment to modernist principles of composition and form.

Kuhn also painted landscapes, often during summers spent away from the city, particularly in Ogunquit, Maine, a popular artist colony. These works, while less numerous than his portraits, often display a similar boldness of execution and simplification of form found in his figurative work. He captured the ruggedness of the coastal scenery or the quietude of rural settings with a direct and unsentimental approach, focusing on essential shapes and strong color contrasts. These explorations in still life and landscape complemented his figurative work, allowing him to continually experiment with formal elements.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Walt Kuhn's mature artistic style represents a unique synthesis of American realism and European modernist influences. His early training and illustration work provided a foundation in solid draftsmanship and observation. His exposure to European art, particularly Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Expressionism, profoundly shaped his approach to form, color, and emotional content. The structural emphasis of Cézanne, the bold color of Matisse, and the emotional intensity of Expressionists (perhaps echoing the work of artists like Georges Rouault, who also painted clowns with deep pathos) are all discernible threads in his work.

However, Kuhn forged these influences into a distinctly personal style. Key characteristics include: strong, decisive outlines; simplification and flattening of forms, often giving figures a monumental or iconic presence; bold, often non-naturalistic use of color to convey emotion and structure; direct, confrontational compositions, especially in portraiture; and a focus on psychological depth rather than narrative detail. His technique was typically direct and painterly, applying paint thickly in places, emphasizing the materiality of the medium. He achieved a powerful balance between formal rigor and expressive content, particularly in his iconic performer portraits.

Collaborations and Artistic Circles

Beyond his individual practice, Kuhn remained connected to the art world through various roles. His work organizing the Armory Show involved intense collaboration with Arthur B. Davies, Walter Pach, and the other members of the AAPS. Following the show, he acted as an advisor to important collectors who were embracing modern art, including John Quinn, whose collection became legendary, and Lillie P. Bliss, one of the key founders of the Museum of Modern Art. These connections placed Kuhn at the heart of the developing infrastructure for modern art in America.

He also maintained relationships with fellow artists, both progressives and those with more traditional leanings. His involvement in artist clubs like the Penguin Club provided spaces for interaction and mutual support. Later in his career, he also took on teaching roles, notably at the Art Students League of New York, where he had his first retrospective exhibition in 1939. While sometimes perceived as gruff or solitary, Kuhn played a significant role within the artistic community, bridging the gap between European avant-gardism and the American scene. His network included artists across various styles, from the urban realists associated with Robert Henri and the Ashcan School to fellow modernists like Marsden Hartley.

Later Years: Health, Isolation, and Tragedy

Kuhn's later life was marked by recurring health problems and increasing personal struggles. A severe bout with a duodenal ulcer in 1925 required hospitalization and seemed to deepen his commitment to his art, perhaps by confronting him with his own mortality. He continued to work prolifically through the 1930s and 1940s, producing many of his most powerful performer portraits during this time. However, reports suggest he became more isolated and prone to mood swings.

His final years were tragic. In 1948, suffering from declining mental health, he was admitted to an institution. There were unconfirmed rumors surrounding a potential suicide attempt, adding a layer of mystery to his decline. His physical health also deteriorated. Walt Kuhn died on July 13, 1949, in White Plains, New York, due to a perforated ulcer. A poignant anecdote relates that his wife, Vera, and daughter, Brenda, placed his favorite paintbrushes in his pocket before his burial, a final tribute to the art that had consumed his life. His life reflected a tension between his public role as a robust promoter of modernism and a more private, perhaps tormented, inner world, a duality sometimes mirrored in the melancholic dignity of his painted performers.

Critical Reception and Historical Legacy

Walt Kuhn's historical position is multifaceted. He is universally acknowledged for his indispensable role in organizing the 1913 Armory Show, an event that remains a landmark in American cultural history. This achievement alone secures his place as a key facilitator of American modernism. His efforts helped to educate American artists and audiences, challenge entrenched academicism, and stimulate the market for modern art.

As a painter, his reputation rests primarily on his compelling portraits of performers from the 1920s onward. These works are praised for their psychological insight, formal strength, and unique blend of modernist aesthetics with empathetic observation. They are considered significant contributions to American figurative painting in the 20th century. His work is held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the National Gallery of Art.

Critical reception during his lifetime and afterward has sometimes been mixed. While recognized for his Armory Show role, some later critics viewed his painting style as somewhat conservative compared to the more radical abstraction that developed subsequently. However, contemporary reassessments emphasize the power and originality of his best work, particularly his ability to convey complex human emotions through simplified forms and bold execution. He remains a vital figure, representing a specific and powerful vein of American modernism that retained strong ties to representation and human subjects.

Conclusion

Walt Kuhn's career embodies the dynamism and contradictions of American art in the first half of the 20th century. He was a bridge figure: connecting European avant-garde ideas with the American scene, linking the world of commercial illustration with fine art, and merging modernist formal concerns with deeply felt human subjects. His organizational drive gave America the Armory Show, an event whose repercussions are still felt today. His paintings, especially the starkly compelling portraits of clowns and showgirls, offer a unique window into the world of performance and the human psyche. Though his later years were shadowed by illness and personal difficulties, Walt Kuhn's legacy as both a catalyst for modernism and a distinctive painter of the American scene remains secure and significant.