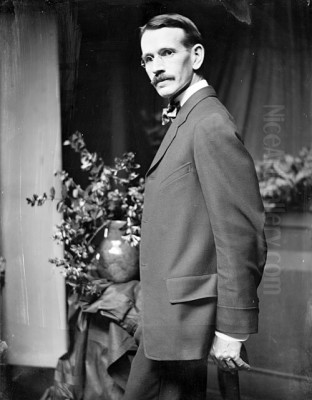

Arthur Bowen Davies stands as a complex and pivotal figure in the narrative of American art history. Active during a period of profound transition, from the late nineteenth century into the early decades of the twentieth, Davies (1862-1928) was not only a prolific painter and printmaker but also a crucial organizer and advocate who helped shape the course of modern art in the United States. His own artistic output, characterized by idyllic, dreamlike visions often populated by ethereal figures, presents a unique blend of traditional influences and modernist sensibilities. Yet, his most enduring legacy might lie in his instrumental role in orchestrating the groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show, an event that irrevocably altered America's relationship with the avant-garde.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Utica, New York, in 1862 to parents of British and Welsh descent, Arthur B. Davies displayed an early inclination towards art. His initial encouragement came from his family environment and notably from Dwight Williams, a local landscape painter who provided early guidance. This foundational exposure to art set the stage for his future pursuits. The family's relocation to Chicago in 1878 marked a significant step in his formal training, as Davies enrolled at the Chicago Academy of Design (later the Art Institute of Chicago).

His time in Chicago was formative, though his path wasn't solely confined to the studio. For a brief period, Davies gained practical experience working as an engineering draftsman for a railroad project extending through Mexico and New Mexico. This experience, though seemingly distant from fine art, may have honed his skills in precision and observation. However, the pull of the art world proved stronger. By 1886 or 1887, Davies had moved to New York City, the burgeoning center of American art.

In New York, Davies supported himself by working as an illustrator for popular publications like Century Magazine and the children's magazine St. Nicholas. This commercial work provided financial stability while allowing him to immerse himself in the city's vibrant artistic milieu. He furthered his education by studying at the prestigious Art Students League, a hub for aspiring artists seeking instruction outside the more rigid confines of the National Academy of Design. During these years, his personal style began to coalesce, initially showing the influence of the Tonalist and Symbolist tendencies prevalent in late 19th-century American painting, echoing the moody landscapes of George Inness and the mystical visions of Albert Pinkham Ryder.

Developing a Unique Style: Arcadia and Inhalation

Davies rapidly distinguished himself from many of his contemporaries through his distinctive subject matter and style. He became best known for his lyrical, often Arcadian, compositions featuring graceful, elongated figures – frequently female nudes – set within idealized landscapes. These works evoke a sense of timelessness, drawing inspiration from classical mythology, Renaissance art, and Symbolist poetry. His paintings often feature nymphs, unicorns, and allegorical figures, rendered with a delicate touch and a harmonious, often muted, color palette.

His style synthesized various influences. The dreamlike quality and emphasis on mood connect him to Symbolism, particularly the work of European artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. His appreciation for graceful lines and decorative compositions shows an affinity with Art Nouveau aesthetics. Furthermore, Davies deeply admired the masters of the Italian Renaissance, particularly the Venetian painters Giorgione and Titian, whose pastoral scenes and poetic use of color resonated with his own artistic aims. He sought to capture a similar sense of harmony and idealized beauty, albeit filtered through a distinctly modern sensibility.

A fascinating aspect of Davies's artistic philosophy was his "Inhalation Theory," developed in collaboration with the archaeologist Gustavus Eisen. This theory posited that the depiction of figures caught in the subtle moment of inhalation could imbue a work of art with a sense of life and continuous energy. Davies applied this principle across various media, believing it captured the vital rhythm of existence. This theoretical underpinning adds another layer to the understanding of his serene yet subtly dynamic figures. Early representative works like Maya, Mirror of Illusions and Dawn exemplify this unique blend of influences and theories, showcasing his signature elongated forms in dreamlike, symbolic settings.

The Eight and Rebellion Against the Academy

Davies was not content to merely pursue his personal artistic vision in isolation. He became actively involved in the progressive art movements of his time. He was a key member of "The Eight," a group of artists who united in opposition to the conservative exhibition policies and aesthetic dominance of the National Academy of Design. Led ideologically by the charismatic painter and teacher Robert Henri, the group championed artistic freedom and sought to depict a broader range of subjects, including contemporary urban life.

While Davies's idyllic and mythical themes differed significantly from the gritty urban realism favored by other members of The Eight, such as John Sloan, William Glackens, Everett Shinn, and George Luks, he shared their fundamental belief in the artist's right to independent expression and their frustration with the academic establishment. The group also included Ernest Lawson and Maurice Prendergast, whose styles were closer to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, respectively, highlighting the diversity within this alliance.

In 1908, The Eight held a landmark exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York. Organized largely in protest after works by Henri, Sloan, and Glackens were rejected by the National Academy, the show was a critical success and a significant challenge to the established art hierarchy. It signaled a growing desire for new forms of expression and paved the way for further independent exhibitions. Davies's participation underscored his commitment to artistic pluralism and his role as a bridge between different emerging factions within American art. His association with The Eight solidified his position as a forward-thinking artist willing to challenge convention.

The Armory Show: A Pivotal Moment

Arthur B. Davies's most significant contribution to the institutional history of American modernism was undoubtedly his leadership role in organizing the International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show, held in 1913 at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City. Serving as president of the organizing body, the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), Davies was the driving force behind this ambitious and transformative event.

Working closely with fellow artists Walt Kuhn (the AAPS secretary) and Walter Pach (an artist and agent fluent in European art circles), Davies embarked on a crucial trip to Europe in late 1912. Their mission was to select cutting-edge works from the European avant-garde to exhibit alongside contemporary American art. Davies, despite his own more lyrical style, possessed a remarkably open mind and a keen eye for radical innovation. He was instrumental in choosing works that would introduce American audiences to Fauvism, Cubism, and other revolutionary movements.

The Armory Show was unprecedented in its scale and scope, featuring some 1,300 works by over 300 artists. It included paintings and sculptures by European luminaries such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Constantin Brancusi, Wassily Kandinsky, Francis Picabia, and, most notoriously, Marcel Duchamp, whose Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 became the succès de scandale of the exhibition. The show also prominently featured Symbolist precursors like Odilon Redon, whose work held a particular appeal for Davies. Alongside these European innovators, works by American artists, including members of The Eight and Davies himself, were displayed.

The impact of the Armory Show was immediate and profound. It generated enormous public interest, attracting vast crowds and sparking intense debate and controversy in the press. While many critics and traditionalists were outraged by the radical European art, branding it as anarchic and incompetent, many younger artists and collectors were exhilarated and inspired. The exhibition fundamentally shifted the landscape of American art, accelerating the acceptance of modernism and challenging artists to engage with new aesthetic possibilities. Davies's vision, organizational skill, and willingness to champion challenging art were central to the show's success and its lasting legacy.

Artistic Evolution Post-Armory Show

The Armory Show not only transformed the American art scene but also had a discernible impact on Davies's own artistic practice. Exposed firsthand to the structural innovations of Cubism and the expressive freedom of Fauvism during the selection process and the exhibition itself, Davies began to incorporate elements of these styles into his work. This period saw a move towards more fragmented forms, angular rhythms, and a bolder, less naturalistic use of color in some of his paintings.

His engagement with Cubism was particularly notable, though characteristically synthesized with his existing style rather than adopted wholesale. Works from the mid-1910s, such as Day of Good Fortune, demonstrate this integration, featuring figures composed of intersecting geometric planes, yet retaining an overall sense of lyrical movement and decorative harmony. He explored the analysis of form and the representation of multiple viewpoints, characteristic of Cubism, but applied these techniques to his familiar themes of dance, mythology, and idealized nature.

This phase did not represent a complete break from his earlier work but rather an expansion of his artistic vocabulary. He continued to produce paintings in his more established Symbolist-inspired style, but his post-Armory Show work often exhibits a greater formal complexity and dynamism. He seemed less interested in the analytical rigor pursued by Picasso or Braque and more focused on adapting Cubist devices to enhance the rhythmic and expressive qualities of his compositions. This period highlights Davies's capacity for assimilation and his ongoing quest to find visual languages adequate to his unique poetic vision.

Printmaking and Other Media

While primarily known as a painter, Arthur B. Davies was also a highly accomplished and prolific printmaker. Throughout his career, he explored various print techniques, including etching, aquatint, lithography, and drypoint, demonstrating considerable technical skill and sensitivity to the unique possibilities of each medium. His prints often revisit the themes found in his paintings – Arcadian landscapes, dancing figures, mythological subjects – but translated into the distinct linear and tonal language of printmaking.

His work in printmaking allowed him to experiment with line, texture, and composition in different ways. Lithography, in particular, offered a fluidity well-suited to his graceful figuration, while etching and drypoint enabled him to create works of delicate intimacy and atmospheric depth. He produced hundreds of prints, which were widely collected and helped to disseminate his artistic vision. These works are not mere reproductions of his paintings but stand as independent artistic achievements, showcasing his mastery of graphic expression.

Furthermore, Davies extended his artistic interests beyond painting and printmaking into the realm of decorative arts. Notably, he designed tapestries, collaborating with workshops to translate his distinctive imagery into woven form. This interest in tapestry design aligns with his overall aesthetic, which often emphasized decorative harmony and rhythmic pattern. His engagement with multiple media underscores his versatile talent and his holistic approach to art-making, seeing connections between fine art and decorative applications, perhaps influenced by the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement or the integrated artistic visions of Symbolist predecessors.

Key Patrons and Relationships

An artist's career is often shaped by key relationships with dealers, patrons, and fellow artists, and Davies was no exception. An early and important supporter was the New York art dealer William Macbeth, whose Macbeth Galleries provided a crucial venue for progressive American artists. Macbeth not only exhibited Davies's work, including the landmark 1908 show of The Eight, but also provided personal support. It was Macbeth who reportedly financed Davies's first significant trip to Europe in the 1890s, an experience that broadened his artistic horizons.

Perhaps Davies's most consequential relationship with a patron was his long association with Lillie P. Bliss. A discerning and adventurous collector of modern art, Bliss relied heavily on Davies's advice in building her remarkable collection. Davies guided her acquisitions, introducing her to the work of both European and American modernists, including Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Henri Matisse, and others whose work she might not have encountered otherwise. Davies acted as her trusted advisor and agent, shaping one of the most important early collections of modern art in America.

This relationship had a profound posthumous impact. Upon her death in 1931, Lillie P. Bliss bequeathed the core of her collection, along with funds, to establish a new museum dedicated to modern art. This bequest was instrumental in the founding of The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Alfred H. Barr Jr., MoMA's founding director, acknowledged the significance of the Bliss collection, and by extension, Davies's role in its formation. Thus, Davies's influence extended beyond his own art and organizational activities into the very foundation of one of the world's leading modern art institutions.

Personal Life and Controversy: A Hidden Duality

While Arthur B. Davies cultivated an image as a refined, almost ethereal artist dedicated to his Arcadian visions, his personal life concealed a startling duality that remained hidden until after his death. In 1892, he married Dr. Virginia Meriwether, a physician from a respected family. They settled in Congers, New York, north of the city, and raised two sons. To the outside world, this appeared to be a conventional, respectable family life, fitting for a successful artist.

However, Davies simultaneously maintained a secret second life in New York City. For years, he had a relationship with Edna Potter, a dancer who became one of his favorite models and his mistress. Under the assumed name "David A. Owen," Davies established a separate household with Edna, and they had a daughter together, Ronnie. Edna and her daughter believed "David Owen" was their husband and father, unaware of his real identity or his other family. Davies meticulously managed this deception, dividing his time and resources between his two lives.

This hidden life inevitably placed strains on both relationships. Edna Potter's role as a model was crucial to Davies's art, but after the birth of their daughter around 1912, her availability likely changed, potentially impacting his work. The full extent of his double life only came to light after his sudden death from a heart attack while traveling in Florence, Italy, in 1928. The revelation shocked both families and the art world, complicating the legacy of an artist known for his seemingly serene and idealistic work. This hidden aspect of his life adds a layer of profound complexity to his biography, revealing a man capable of deep secrecy alongside his public artistic persona.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

In the years following the Armory Show, Davies continued to be a respected figure in the American art world, though perhaps less central to the avant-garde movements he had helped introduce. He continued to paint, print, and design, refining his unique synthesis of tradition and modernity. His work remained popular with certain collectors, including Lillie P. Bliss and Duncan Phillips (founder of The Phillips Collection). He traveled frequently, seeking inspiration in Europe and across the United States.

His sudden death in Florence in October 1928 brought an end to a prolific and influential career. The subsequent revelation of his secret second family created a posthumous scandal but also led to a reassessment of his life and work. In 1930, the Metropolitan Museum of Art held a major memorial exhibition, acknowledging his significant contributions to American art. The exhibition showcased the breadth of his output, from his early Tonalist-influenced works to his later, more abstract compositions and his extensive print oeuvre.

Arthur B. Davies's legacy is multifaceted. He remains best known for his pivotal role in organizing the Armory Show, an event that fundamentally altered the course of American art. He was also a central figure in The Eight, challenging academic conservatism. As an artist, his work occupies a unique space, blending Symbolist dreaminess, Renaissance grace, and modernist experimentation. While his idyllic style fell out of favor during the mid-20th century dominance of Abstract Expressionism, recent scholarship has shown renewed interest in his complex position as a bridge figure between nineteenth-century romanticism and twentieth-century modernism. His influence as an advisor to Lillie P. Bliss, directly impacting the founding collection of MoMA, further cements his enduring importance in the institutional history of modern art.

Conclusion: An Artist of Contrasts

Arthur B. Davies remains an intriguing and somewhat paradoxical figure in American art history. He was an artist of idyllic dreams who played a key role in unleashing the radical forces of European modernism onto the American scene. His personal style, rooted in Symbolism and Renaissance ideals, stood in contrast to the urban realism of many of his colleagues in The Eight and the avant-garde art he championed at the Armory Show. He was a respected public figure who maintained a secret private life marked by profound deception.

Despite these contrasts, or perhaps because of them, Davies exerted a significant influence. His leadership brought about the Armory Show, arguably the single most important art exhibition ever held in the United States. His advocacy supported fellow artists and shaped major collections. His own art, with its distinctive blend of lyricism, mythology, and formal experimentation, continues to fascinate. While perhaps not as consistently innovative as some of the European artists he introduced, Arthur B. Davies was an indispensable catalyst, a complex individual, and a creator of a unique and enduring body of work that reflects the transitional spirit of his time. His contributions ensure his place as a vital, if enigmatic, presence in the story of American modernism.