Wilhelm Morgner stands as a significant, albeit tragically short-lived, figure in the vibrant landscape of early 20th-century German Expressionism. Born in an era of artistic ferment and societal change, Morgner forged a powerful and distinctive visual language characterized by dynamic compositions, intense color, and a profound spiritual depth. His life, cut short by the ravages of World War I, left behind a body of work that continues to resonate, offering a poignant glimpse into a talent that was rapidly ascending towards artistic maturity. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of Wilhelm Morgner, a painter and illustrator whose contributions to Expressionism remain vital and compelling.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Soest

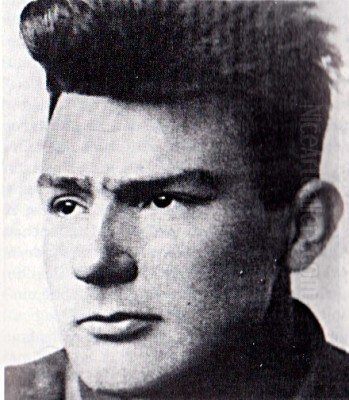

Wilhelm Morgner was born on January 27, 1891, in the small town of Soest, Westphalia, Germany. His familial background was modest; his father, a former military band musician, later worked as a railway employee. Unfortunately, Morgner's father passed away when Wilhelm was still young, leaving his mother to raise him and his sister. His mother possessed an artistic sensibility herself, a trait that would later manifest in her publication of a poetry collection in 1920. This maternal influence likely played a role in nurturing young Wilhelm's burgeoning interest in the arts.

Despite his mother's hopes that he might pursue a more conventional path, perhaps as a pastor, Morgner's true calling lay in the world of visual art. His passion was undeniable, and after a brief period in secondary school, he made the decisive step to dedicate himself to artistic training. This decision marked the beginning of a journey that, though brief, would see him engage with some of the most progressive artistic ideas of his time.

Formative Years: Worpswede and the Guidance of Georg Tappert

The year 1908 was pivotal for Morgner. Acting on the advice of the painter Otto Modersohn, a prominent figure associated with the Worpswede artists' colony, Morgner traveled to this renowned artistic haven. Worpswede, near Bremen, had become a center for artists seeking to escape academic constraints and engage more directly with nature and rural life. Figures like Fritz Mackensen, Hans am Ende, and Paula Modersohn-Becker had already established the colony's reputation.

In Worpswede, Morgner began his formal art education under the tutelage of Georg Tappert. Tappert, himself an Expressionist painter, proved to be an influential mentor. He not only imparted knowledge of modern art theories and techniques but also fostered a close, supportive friendship with his student. Tappert's teaching methods included extensive outdoor sketching sessions, encouraging Morgner to observe and interpret the world around him directly. This period was crucial for Morgner's development, exposing him to new artistic currents and helping him to hone his technical skills.

During these formative years, Morgner absorbed a range of influences. He was particularly drawn to the burgeoning modern art movements. The innovations of Post-Impressionism, especially the vibrant color and emotional intensity of Vincent van Gogh's work, left a lasting impression. He also studied the principles of Pointillism, a technique pioneered by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, which involved applying small, distinct dots of color to form an image. The bold Fauvist palette of artists like Henri Matisse also contributed to his evolving aesthetic.

The Emergence of an Expressionist Voice

As Morgner matured artistically, his style increasingly aligned with German Expressionism. This movement, which flourished in the early decades of the 20th century, prioritized subjective emotion and inner vision over objective reality. Artists like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff of the Dresden-based group Die Brücke (The Bridge), and Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and August Macke of the Munich-based Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), were pushing the boundaries of color, form, and representation.

Morgner's work from this period is characterized by its bold and often non-naturalistic use of color, creating a powerful emotional impact. His compositions became increasingly dynamic, filled with a sense of rhythm and movement. He frequently depicted scenes of rural labor, a theme common in Worpswede, but he imbued these subjects with a deeper, almost spiritual significance. His figures, often simplified or elongated, convey a sense of raw energy and connection to the earth. He sought to express an inner truth, a spiritual essence, rather than merely a surface appearance.

Between 1910 and 1913, Morgner's talent began to gain wider recognition. He participated in significant exhibitions, notably those of the "New Secession" in Berlin. The New Secession, formed in 1910 by artists (including Max Pechstein and Georg Tappert) who had broken away from the more conservative Berlin Secession, provided a platform for avant-garde art. Exhibiting alongside prominent Expressionists helped to establish Morgner's reputation as a promising young artist.

Representative Works and Stylistic Characteristics

Wilhelm Morgner's oeuvre, though created over a relatively short span, includes a remarkable number of paintings, watercolors, woodcuts, and drawings. His works demonstrate a clear progression from early, more naturalistic studies to a highly personal and increasingly abstract form of Expressionism.

One of his notable woodcuts, Ernte (Harvest), created in 1912, exemplifies his interest in rural themes and the expressive power of the print medium. The stark contrasts and simplified forms inherent in woodcut suited the Expressionist aesthetic, allowing for direct and forceful statements.

The painting Feldweg (Field Path), also from 1912, showcases his move towards a more abstract and emotionally charged style. The colors are bold and applied with a visible energy, and the figures within the landscape are distorted, conveying a sense of movement and perhaps an underlying tension or spiritual fervor. The work prioritizes rhythmic composition and emotional resonance over literal depiction.

His religious subjects, such as Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, are particularly powerful. In this work, Morgner employs bright, almost incandescent colors and silhouetted forms to create a scene of dramatic intensity. The figures are stylized, and the composition is imbued with a dynamic energy that captures the spiritual fervor of the event. Another religious piece, Christ before the High Council, further demonstrates his ability to convey profound emotional and spiritual themes through his distinctive Expressionist lens.

A work like The Man with Barrow (1911) shows his engagement with the human figure and labor, rendered with strong outlines and a focus on the physicality and dignity of the subject. His color choices, often involving striking juxtapositions like deep reds and yellows, contribute significantly to the visual impact and emotional tenor of his paintings.

Towards the end of his brief career, Morgner began to explore even more abstract and symbolic forms, as seen in works like Astral Composition VI (1912). These pieces hint at a developing interest in surreal or cosmic themes, pushing his art towards a non-representational language that sought to visualize inner spiritual states or universal forces. The "Astral Compositions" are characterized by their ornamental, almost abstract linear patterns and vibrant color fields, suggesting a move towards a more purely formal and spiritual art, akin to the explorations of Kandinsky or Franz Marc.

His works consistently feature an emphasis on strong lines, rhythmic patterns, and a simplification of forms to their essential elements. He was not afraid to distort reality to heighten expressive impact, a hallmark of the Expressionist movement.

The Crucible of War: Service and Sacrifice

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought a brutal interruption to Morgner's burgeoning career and, ultimately, his life. Like many young men of his generation, including fellow artists such as Franz Marc and August Macke, Morgner was conscripted into military service. He was called up in 1915.

His time in the military was arduous. Despite suffering from health issues, including a foot injury that led to a period of hospitalization, he served on the front lines. Even amidst the horrors and privations of war, Morgner continued to create, producing a number of sketches that document his experiences and reflect his unwavering artistic impulse. These wartime drawings offer a poignant testament to his dedication.

He served on the Eastern Front, where his bravery and service earned him a promotion to the rank of lieutenant and the award of the Iron Cross, Second Class. However, his return to the Western Front would prove fatal.

A Tragic End and Immediate Aftermath

Wilhelm Morgner's life was tragically cut short on August 16, 1917. During the fierce fighting near Langemarck in Flanders, Belgium, a key site of brutal trench warfare, he was captured by British soldiers. Reports indicate that he was killed while resisting his captors. He was only 26 years old.

The loss of Wilhelm Morgner was a profound blow to the German art world. His teacher and friend, Georg Tappert, deeply felt his absence. In 1920, Tappert undertook the important task of cataloging Morgner's artistic estate. His meticulous inventory recorded an impressive output for such a young artist: 235 paintings, an astonishing 1920 watercolors and drawings, and 67 prints. This catalog remains a crucial resource for understanding the scope and development of Morgner's work.

The early deaths of artists like Morgner, Marc, and Macke due to the war represented an immeasurable loss of creative potential for German Expressionism and for modern art as a whole. One can only speculate on the directions Morgner's art might have taken had he lived.

The Nazi Era: Condemnation as "Degenerate Art"

The rise of the Nazi regime in Germany in the 1930s brought a dark period for modern art. The Nazis, with their reactionary cultural ideology, condemned Expressionism and other avant-garde movements as "Entartete Kunst" or "Degenerate Art." They viewed such art as un-German, Jewish-influenced, or Bolshevik, and saw it as a symptom of cultural decay.

Wilhelm Morgner's work, like that of many of his contemporaries including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Emil Nolde, Max Beckmann, Paul Klee, and Oskar Kokoschka, fell victim to this cultural persecution. In 1937, a significant number of his works were confiscated from German museums. Some were included in the infamous "Degenerate Art" exhibition, a propaganda show organized by the Nazis in Munich to ridicule and defame modern art. This exhibition toured to other cities, including Berlin. Many of the confiscated artworks were subsequently sold abroad, destroyed, or simply disappeared. This systematic suppression aimed to erase these artists from Germany's cultural heritage.

Post-War Rediscovery and Enduring Legacy

After the devastation of World War II and the fall of the Nazi regime, there was a gradual process of cultural rebuilding in Germany. This included a re-evaluation and rediscovery of the artists who had been persecuted and suppressed. Wilhelm Morgner's work began to receive renewed attention, particularly from the 1950s onwards. Art historians and curators recognized the quality and significance of his contributions to Expressionism.

A crucial step in preserving and promoting his legacy was the establishment of the Wilhelm Morgner Museum (Museum Wilhelm Morgner) in his hometown of Soest in 1962 (though initiatives began earlier, with a prize established in 1953). The museum became the primary repository for his estate, housing a substantial collection of his paintings, watercolors, drawings, and prints. Today, it holds over 60 oil paintings and more than 400 works on paper by Morgner, providing a comprehensive overview of his artistic development from his early realistic works to his mature Expressionist and near-abstract compositions. The museum also features the "Raum Schroth," dedicated to concrete and constructive art, creating a dialogue between Morgner's historical expressionism and contemporary non-representational art.

To further honor his memory and support contemporary artists, the Wilhelm Morgner Prize was established in 1953. This prize is awarded to young artists working in the spirit of expressive art, ensuring that Morgner's name continues to be associated with artistic innovation and vitality.

Artistic Connections and Contemporaries

Wilhelm Morgner did not work in isolation. His artistic journey was shaped by his interactions with teachers, fellow artists, and the broader artistic currents of his time.

His most significant mentor was undoubtedly Georg Tappert. Tappert not only provided formal instruction but also acted as a supportive friend and a crucial link to the Berlin art scene. Tappert himself was an active participant in Expressionist circles, co-founding the New Secession.

Morgner's work shows affinities with the artists of Die Brücke, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Pechstein, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. While he was not a formal member of the group, he shared their commitment to expressive intensity, bold color, and often, a focus on raw, primal emotion. His works were exhibited alongside theirs, indicating a shared artistic space and mutual awareness.

He was also aware of the developments within Der Blaue Reiter, the other major German Expressionist group. The spiritual aspirations and move towards abstraction seen in the work of Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, and August Macke find echoes in Morgner's later, more abstract compositions, particularly the "Astral Compositions." Franz Marc, known for his vibrantly colored animal paintings imbued with spiritual symbolism, was an artist whose work Morgner admired.

The influence of Vincent van Gogh is palpable in Morgner's energetic brushwork and emotionally charged use of color. Similarly, the innovations of French Fauvists like Henri Matisse, with their liberation of color from purely descriptive purposes, resonated with Morgner's own explorations. Even earlier masters like Rembrandt, with his dramatic use of light and shadow and profound humanism, and Impressionists like Claude Monet, with their focus on capturing fleeting moments and the effects of light, formed part of the broader artistic heritage that Morgner absorbed and transformed.

His early connection to Worpswede also places him in the context of artists like Otto Modersohn and Paula Modersohn-Becker, who, though working in a different vein, shared a desire to break from academicism and find new forms of expression rooted in personal experience and the natural world.

The Enduring Impact of Wilhelm Morgner

Despite a career that spanned less than a decade, Wilhelm Morgner made a lasting contribution to German Expressionism. His work is distinguished by its intense emotional power, its innovative use of color and form, and its underlying spiritual quest. He successfully synthesized influences from Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and the burgeoning abstract tendencies of his time into a highly personal and compelling artistic language.

Morgner is often seen as a transitional figure, whose art was moving from figurative Expressionism towards a greater degree of abstraction when his life was cut short. His exploration of rhythmic line, dynamic composition, and the symbolic power of color places him firmly within the avant-garde of his era.

The tragic circumstances of his early death in World War I, followed by the suppression of his work during the Nazi era, meant that his art was not as widely known for a period as that of some of his longer-lived contemporaries. However, the post-war efforts to reclaim and celebrate his legacy have ensured his rightful place in the annals of art history. The Wilhelm Morgner Museum in Soest stands as a permanent tribute to his genius, allowing contemporary audiences to experience the power and beauty of his art.

Wilhelm Morgner's story is a poignant reminder of the fragility of life and the immense loss that war inflicts on human creativity. Yet, it is also a testament to the enduring power of art. His paintings, drawings, and prints continue to speak to us, conveying a vibrant spirit and an unwavering commitment to artistic expression that even the darkest forces of history could not entirely extinguish. He remains a vital figure for understanding the depth, diversity, and emotional intensity of German Expressionism.